The Monastic Church of the Holy Emperors Constantine and Helena, view from the southwest, Hurezi Monastery, Wallachia, Romania, 1691–92 (photo: Ymblanter, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Hurezi (Horezu) Monastery, a UNESCO monument since 1993, is filled with murals and paintings from floor to ceiling. It is one of the best preserved examples of this type of church in Wallachia, what is now modern-day Romania. The main church of the monastery was commissioned by the local ruler Constantin Brâncoveanu and designed as his family mausoleum. It was also meant to reflect theological, spiritual, and political messages related to the networked position of Wallachia at the turn of the 18th century.

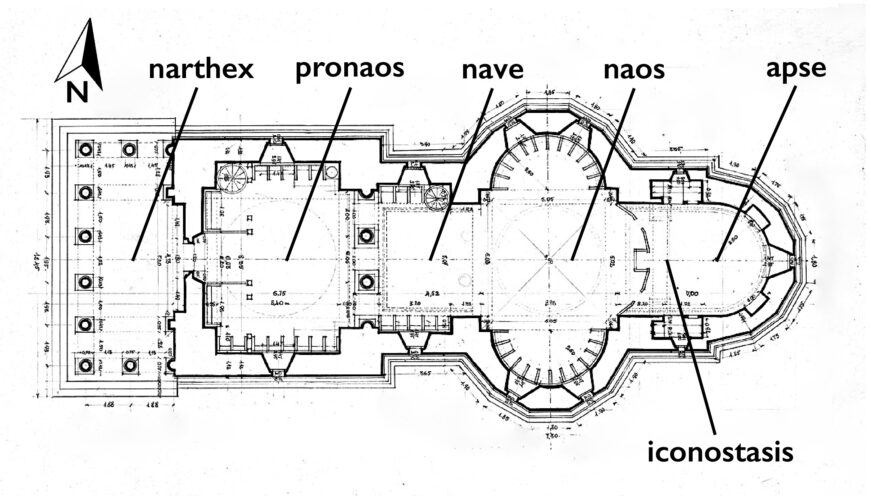

Plan for The Monastic Church, Hurezi (Horezu) Monastery, Wallachia, Romania, 1691–92 (photo: Relevee, University of Architecture and Urban Planning, Bucharest)

The large church of the monastery—begun in 1690 and dedicated to the Holy Emperors Constantine and Helena—was built on a triconch plan, consisting of a central liturgical space surrounded by the sanctuary apse and two lateral apses to the north and south. It also features two domes, one over the naos and the other over the enlarged pronaos. A porch to the west marks the entrance into the church and protects the richly carved stone entrance. In its architecture and decoration, the church at Hurezi Monastery follows a long Wallachian tradition of princely churches.

Iconostasis, The Monastic Church of the Hurezi Monastery, Horezu, Romania, 1692–94 (photo: Richard Mortel, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The murals

The murals of the church and the icons of the richly gilded and painted iconostasis—one of the most distinguished pieces of sculpture from the period—were completed by 1694. The image cycles recall Byzantine (Eastern Christian) models in their evolved post-Byzantine forms, while also incorporating subjects inspired by Kyivan book engravings. These iconographies were designed under the guidance of Abbot John, who was a learned theologian and scholar. Through his involvement in the decoration of the church, he sought to meet both the liturgical and pastoral requirements of the monastic community and reflect the political and cultural ambitions of the patron.

In the church’s apse, a majestic image of the enthroned Theotokos (Virgin Mary, Mother of God) accompanies a cycle of scenes from her childhood. These include the Vision of the Burning Bush of Moses and surmounts, as a prologue to the Incarnation, the scene of the Communion of the Apostles, bordered by evangelical scenes of healings, the Parable of the Ten Virgins, and the Sacrifice of Abraham.

Theotokos (Virgin Mary, Mother of God), The Monastic Church of the Hurezi Monastery, Horezu, Romania, 1692–94 (photo: author)

The nave features the Celestial Liturgy in the dome and evangelical cycles. A cycle of the Martyrdom of the Apostles was painted in the windows of the sanctuary and the nave. It was a novelty in Wallachia at the time, with Macedonian and Epirote precedents. To the west, a short cycle of the Dormition of the Mother of God together with the martyrdom of Saint John the Baptist, form a sequence taken from the end of the Eastern Church Calendar (the month of August since the calendar begins on September 1). Numerous other parallels and iconographic micro-structures can be read in the way the scenes are arranged on the interior walls of the church, indicating a carefully designed program of images.

Dormition of the Mother of God and other cycles, The Monastic Church of the Hurezi Monastery, Horezu, Romania, 1692–94 (photo: author)

The pronaos is decorated with the Mother of God Platytera under its dome, accompanied by representations of the stanzas of the Akathistos Hymn. On the walls below, there are scenes related to Sacrifice and Resurrection. This structure mediates the semantic junction between the scenes of the Synaxarion, represented on the vaults of the pronaos, and the figures of the Old Testament patriarchs, represented on the columns that support the arches of the dome. The soffits of the arches display scenes concerning the junction of earth and heaven: Jacob’s Ladder, the Ladder of Saint John Climacus, and the Life of the Prophet Elijah.

Pronaos, eastern tympanum, Life of Saint Constantin and the Battle of Pons Milvius, The Monastic Church of the Hurezi Monastery, Horezu, Romania, 1692–94 (photo: Viorel Maxim)

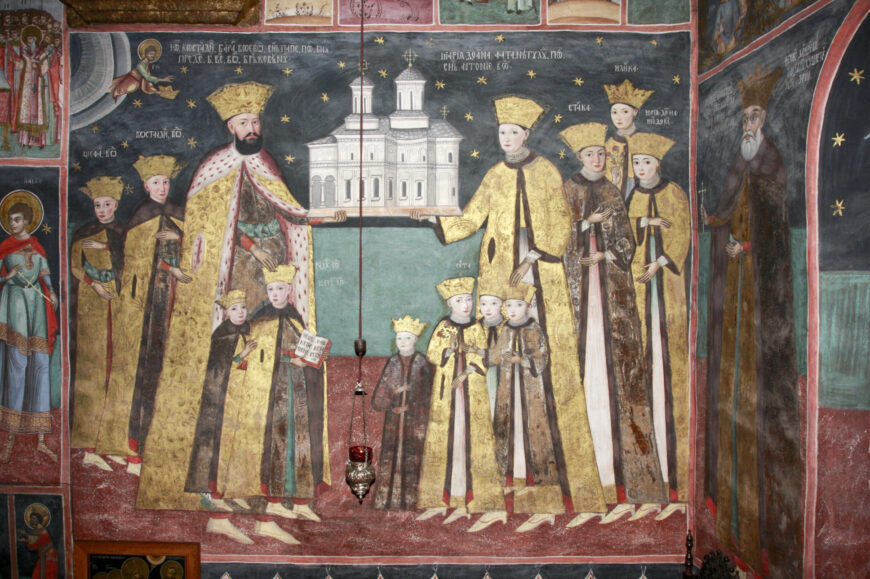

The tympanum of the eastern wall of the pronaos contains a cycle of the life of Saint Constantine, also unique in Wallachia, which opens the “political” program of the lower part of the pronaos. The southern bay of the pronaos was reserved for the grave of the patron and the impressive votive representation of the ruling family: Constantin Brâncoveanu with his wife and 11 children, four boys and seven girls.

Pronaos, eastern wall to the south, Voivode Constantine Brâncoveanu, Lady Maria, and their children, votive painting, 1694 and 18th-century retouchings, The Monastic Church of the Hurezi Monastery, Horezu, Romania, 1692–94 (photo: author)

The walls of the narthex received an extensive genealogical gallery of portraits of the local ruling family, including a series of rulers connected with the Basarab dynasty, which ruled Wallachia in the previous centuries. The presence of Saints Barlaam and Josaphat, Nicodim of Tismana, and Gregory of Decapolis point to local cults of saints linked to the history of the Basarab family in the 16th century.

Three calottes showing Christ in Glory, The Monastic Church of the Hurezi Monastery, Horezu, Romania, 1692–94 (photo: author)

The narthex/porch, covered with three calottes, shows a main representation of Christ in glory on the central vault, surrounded by angels, and Psalms 148–50, between Axions of the Mother of God. The tympana feature four evangelical parables evoking Judgment, similar to examples found in the Epirote context. This suggests a cultural connection between Wallachia and Epiros in the late 17th century. On the eastern wall of the entrance, in a very prominent and visible location, a large Last Judgment is painted. This scene was meant to remind the faithful entering and leaving the church of the judgment at the end of days and the proper path to salvation: through the church. The Genesis cycle is also found in the porch, along with a complete series of the Ecumenical Councils—a program with an eloquent confessional message concerning the true faith.

Our Lady of the Burning Bush painted in the dome of the eastern porch, The Monastic Church of the Hurezi Monastery, Horezu, Romania, 1692–94 (photo: Țetcu Mircea Rareș, CC BY-SA 3.0 RO)

The small porch, added to the façade by Abbot John, has the image of Our Lady of the Burning Bush painted in the dome. This is a Rusian iconographic type popular in icons, and may have reached Wallachia via painted or printed icons. Abbot John, who guided the artistic choices in the iconographic program, was a learned man who was familiar with the theological literature generated by the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra printing press in Kyiv. Several iconographic themes and compositions entered the repertoire of the Wallachian painters via the engravings of the Kyivan books that circulated within Eastern Europe.

Artists and cultural connections

The painters who worked at Hurezi Monastery hailed from local workshops and further afield including several of Greek origin, connected with the Epirot cultural context. They are all known from inscriptions within the church and identified as Constantinos, Andreas, Ioan, Stan, Neagoe, and Ioachim.

The local painters who worked in Constantinos’ team in Wallachia also left their own marks on the mural cycles of the church. Their contributions make one wonder if the Wallachian teammates were apprentices of the Greek painter, or if they were already established painters when they joined his team. What they created at Hurezi Monastery offered examples for the decoration of other local monuments, and became characteristic of the painting style of the Brâncoveanu period.

The half-length portraits of the craftsmen and supervisors painted in the porch to the left of the Heaven scene of the Last Judgment introduce a compositional innovation in the image cycle. Such portraits became more frequent during Brâncoveanu’s times, testifying to the importance of authorship and the agency of the artists in this period.

Porch, eastern wall, to the north: Last Judgment, detail: Heaven, with the portraits of Manea, the master of masons, Istratie the carpenter, and Vucaşin Caragea the stonemason The Monastic Church of the Hurezi Monastery, Horezu, Romania, 1692–94 (photo: Ioan Popa)

Restorations and collections

Hurezi Monastery suffered damages over time, becoming a military headquarters in the Austro-Ottoman war in the 1730s, and then being occupied by the troops of Vidin Pacha Osman Pazvantoğlu in the 1790s–1800s. But from the 18th century onward, the church and the monastery experienced several periods of restorations. In 1827, under the patronage of Grigore Brâncoveanu, the founder Constantin Brâncoveanu’s descendant, the two porches of the church were covered with exterior paintings displaying landscapes with cypress trees. In modern times, a more scrupulous restoration of the entire complex began shortly before the First World War and continued up to 1934. Then, in 1960–64, an in-depth project at the site returned the monument to its original form by removing all the 19th-century interventions. The mural paintings of the church, together with the iconostasis, were restored between 1995 and 2006.

Hurezi Monastery is one rare monument that preserves a multitude of aspects of its artistic patrimony: sculpted stone components, mural paintings, a sculpted and painted iconostasis with icons, liturgical vessels, textiles, and embroideries, as well as manuscripts and printed books. Most of these objects are kept in situ, in the Hurezi complex and monastic museum, while others were brought to the National Museum of Art, Mogoşoaia Palace Museum, and the Library of the Romanian Academy in Bucharest, making them thus available and accessible to wider audiences.