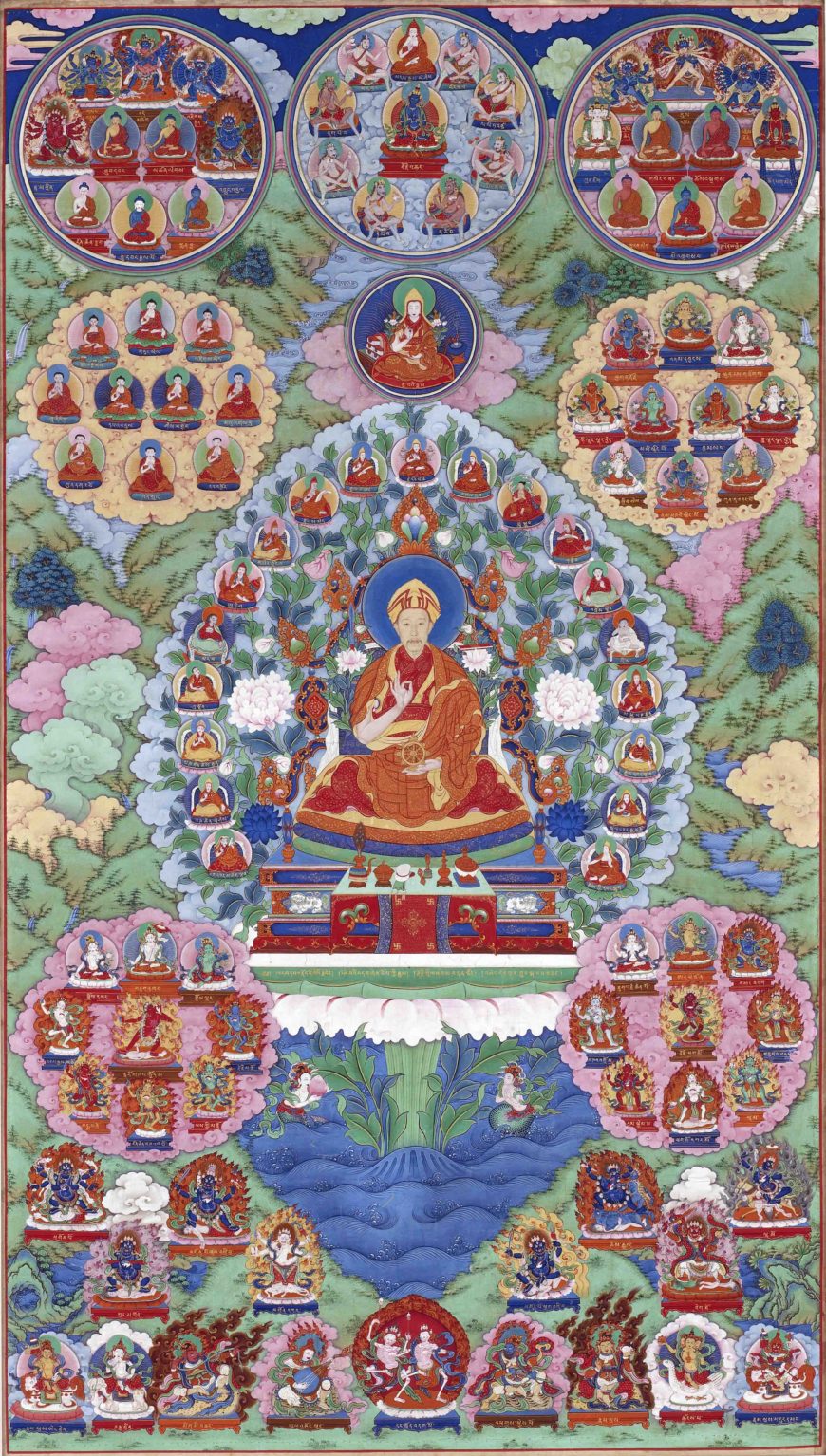

Imperial workshop, with emperor’s face by Giuseppe Castiglione, The Qianlong Emperor as Manjushri, the Bodhisattva of Wisdom, mid-18th century (Qing dynasty, Qianlong reign, China), ink, color, and gold on silk, 113.6 x 64.3 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.: Purchase—Charles Lang Freer Endowment and funds provided by an anonymous donor, F2000.4)

Look at the center of the painting and find the large seated figure wearing red. That is the Qianlong Emperor, who reigned in China from 1735 to 1796. He is shown as an embodiment of Manjushri, the Bodhisattva of Wisdom. The emperor raises his right hand in the gesture of debate or teaching while supporting the wheel of the law in his left.

Emperor (detail), imperial workshop, with emperor’s face by Giuseppe Castiglione, The Qianlong Emperor as Manjushri, the Bodhisattva of Wisdom, mid-18th century (Qing dynasty, Qianlong reign, China), ink, color, and gold on silk, 113.6 x 64.3 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.: Purchase—Charles Lang Freer Endowment and funds provided by an anonymous donor, F2000.4)

He also holds two stems of lotus blossoms on which lie a sutra and a sword—objects typically associated with Manjushri. Qianlong is pictured among 108 deities (an auspicious number in Buddhism) who represent his Buddhist lineage.

Rol-pa’I rdo-rje (detail), imperial workshop, The Qianlong Emperor as Manjushri, the Bodhisattva of Wisdom, mid-18th century (Qing dynasty, Qianlong reign, China), ink, color, and gold on silk, 113.6 x 64.3 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.: Purchase—Charles Lang Freer Endowment and funds provided by an anonymous donor, F2000.4)

In the disk directly above the cloud surrounding the emperor’s image sits his Tibetan Buddhist teacher, Rol-pa’I rdo-rje (1717–1786), with whom he had a very close relationship. The landscape is filled with auspicious clouds. The background is believed to be Wutaishan, a sacred mountain in China. The rich details and bright colors of the painting indicate that it was made for imperial use. The completely accurate depiction of the emperor’s face demonstrates the skill of Giuseppe Castiglione, an Italian Jesuit painter serving at the Qianlong court.

The Qianlong Emperor was the ruler of the world’s largest and most prosperous empire in the eighteenth century. He was also the Chinese emperor who brought the combination of religious and secular authority together in one person. This painting is a testimony to the multicultural nature of his court and empire. A Manchu who ruled over China, the emperor was portrayed in the center of a thangka, a Tibetan Buddhist religious painting. He called upon Giuseppe Castiglione, an Italian missionary known for his skill to capture a person’s true likeness, to paint his face. By having himself portrayed as Manjushri, he positioned himself solidly in the Buddhist hierarchy that was important to the Mongol and Tibetan residents of the empire.

Buddhist figures (detail), imperial workshop, The Qianlong Emperor as Manjushri, the Bodhisattva of Wisdom, mid-18th century (Qing dynasty, Qianlong reign, China), ink, color, and gold on silk, 113.6 x 64.3 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.: Purchase—Charles Lang Freer Endowment and funds provided by an anonymous donor, F2000.4)

This painting belongs to a small group of eight similar, imperially commissioned works that depict the Qianlong Emperor as the bodhisattva Manjushri. The detailed background of the painting, including the jewel-like landscape and 108 Buddhist figures, would have been painted first by an imperial workshop team of Chinese and Tibetan artists. Castiglione would then have been called upon to finish the emperor’s face. This is a standard procedure in Chinese painting workshops. This painting reveals artists from China and Europe collaborating and melding different artistic traditions within a single artwork.

This resource was developed for Teaching China with the Smithsonian, made possible by the generous support of the Freeman Foundation

This resource was developed for Teaching China with the Smithsonian, made possible by the generous support of the Freeman Foundation