Juan Baptista Cuiris, image of Christ made with feathers, c. 1590–1600, 25.4 x 18.2 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

“In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue.” These opening lines to a poem are frequently sung by schoolchildren across the United States to celebrate Columbus’s accidental landing on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola as he searched for passage to India. His voyage marked an important moment for both Europe and the Americas—expanding the known world on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean and ushering in an era of major transformations in the cultures and lives of people across the globe.

When the Spanish Crown learned of the promise of wealth offered by vast continents that had been previously unknown to Europeans, they sent forces to colonize the land, convert the Indigenous populations, and extract resources from their newly claimed territory. These new Spanish territories officially became known as viceroyalties, or lands ruled by viceroys who were second to—and a stand-in for—the Spanish king.

Girolamo Ruscelli, “Nveva Hispania tabvla nova,” engraved map of New Spain, 1599, 19 x 25 cm (David Rumsey Historical Map Collection). Note that at its height, the Viceroyalty of New Spain also included Central America, parts of the West Indies, the southwestern and central United States, Florida, and the Philippines.

Folding Screen with the Siege of Belgrade (front) and Hunting Scene (reverse), c. 1697-1701, Mexico, oil on wood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl, 229.9 x 275.8 cm (Brooklyn Museum)

The Viceroyalty of New Spain

Less than a decade after the Spanish conquistador (conqueror) Hernan Cortés and his men and Indigenous allies defeated the Mexica (Aztecs) at their capital city of Tenochtitlan in 1521, the first viceroyalty, New Spain, was officially created. Tenochtitlan was razed and then rebuilt as Mexico City, the capital of the viceroyalty. At its height, the viceroyalty of New Spain consisted of Mexico, much of Central America, parts of the West Indies, the southwestern and central United States, Florida, and the Philippines. The Manila Galleon trade connected the Philippines with Mexico, bringing goods such as folding screens, textiles, raw materials, and ceramics from around Asia to the American continent. Goods also flowed between the viceroyalty and Spain. Colonial Mexico’s cosmopolitanism was directly related to its central position within this network of goods and resources, as well as its multiethnic population. A biombo, or folding screen, in the Brooklyn Museum attests to this global network, with influences from Japanese screens, Mesoamerican shell-working traditions, and European prints and tapestries. Mexican independence from Spain was won in 1821.

The Viceroyalty of Peru

The Viceroyalty of Peru was founded after Francisco Pizarro’s defeat of the Inka in 1534. Inspired by Cortés’s journey and conquest of Mexico, Pizarro had made his way south and inland, spurred on by the possibility of finding gold and other riches. Internal conflicts were destabilizing the Inka empire at the time, and these political rifts aided Pizarro in his overthrow. While the viceroyalty encompassed modern-day Peru, it also included much of the rest of South America (though the Portuguese gained control of what is today Brazil). Rather than build atop the Inka capital city of Cusco, the Spaniards decided to create a new capital city for Peru: Lima, which still serves as the country’s capital today.

In the eighteenth century, a burgeoning population, among other factors, led the Spanish to split the viceroyalty of Peru apart so that it could be governed more effectively. This move resulted in two new viceroyalties: New Granada and Río de la Plata. As in New Spain, independence movements here began in the early nineteenth century, with Peru achieving sovereignty in 1820.

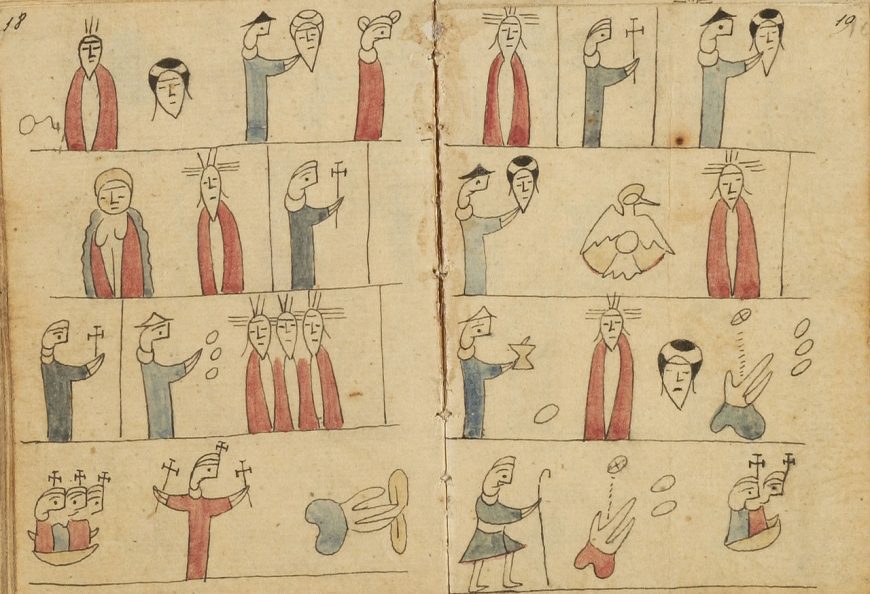

Pictorial Otomí catechism (pictorial prayer book), 1775-1825, Mexico, watercolor on paper, 8 x 6 cm (Princeton University Library)

Evangelization in the Spanish Americas

Soon after the military and political conquests of the Mexica (Aztecs) and Inka, European missionaries began arriving in the Americas to begin the spiritual conquests of Indigenous peoples. In New Spain, the order of the Franciscans landed first (in 1523 and 1524), establishing centers for conversion and schools for Indigenous youths in the areas surrounding Mexico City. They were followed by the Dominicans and Augustinians, and by the Jesuits later in the sixteenth century. In Peru, the Dominicans and Jesuits arrived early on during evangelization.

Convento, San Agustín de Acolman, mid-16th century (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The spread of Christianity stimulated a massive religious building campaign across the Spanish Americas. One important type of religious structure was the convento. Conventos were large complexes that typically included living quarters for friars, a large open-air atrium where mass conversions took place, and a single-nave church. In this early period, the lack of a shared language often hindered communication between the clergy and the people, so artworks played a crucial role in getting the message out to potential converts. Certain images and objects (including portable altars, atrial crosses, frescoes, illustrated catechisms or religious instruction books, prayer books, and processional sculpture) were crafted specifically to teach new, Indigenous Christians about Biblical narratives.

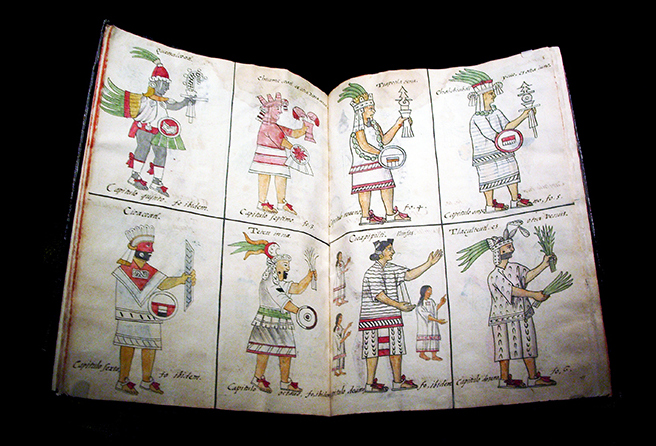

Aztec deities, Bernardino de Sahagún and collaborators, General History of the Things of New Spain, also called the Florentine Codex, vol. 1, 1575-1577, watercolor, paper, contemporary vellum Spanish binding, open (approx.): 32 x 43 cm, closed (approx.): 32 x 22 x 5 cm (Medicea Laurenziana Library, Florence, Italy)

This explosion of visual material created a need for artists. In the sixteenth century, the vast majority of artists and laborers were Indigenous, though we often do not have the specific names of those who created these works. At some of the conventos, missionaries established schools to train Indigenous boys in European artistic conventions. One of the most famous schools was at the convento of Santa Cruz in Tlatelolco in Mexico City, where the Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún, in collaboration with Indigenous artists, created the encyclopedic text known today as the Florentine Codex.

Church of Santo Domingo and Qorikancha, Cusco, Peru (photo: Håkan Svensson, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Strategies of Dominance in the Early Colonial Period

Spanish churches were often built on top of Indigenous temples and shrines, sometimes re-using stones for the new structure. A well-known example is the Church of Santo Domingo in Cusco, built atop the Inka Qorikancha (or Golden Enclosure). You can still see walls of the Qorikancha below the church.

Great Mosque of Córdoba, Córdoba, Spain, begun 786, cathedral added 16th century (photo: Toni Castillo Quero, CC BY-SA 2.0)

This practice of building on previous structures and reusing materials signaled Spanish dominance and power. It had already been a strategy used by Spaniards during the so-called “Reconquest,” or reconquista, of the Iberian (Spanish) Peninsula from its previous Muslim rulers. In southern Spain, for instance, a church was built directly inside the Great Mosque of Córdoba during this period. The reconquista ended the same year Columbus landed in the Americas, and so it was on the minds of Spaniards as they lay claim to the lands, resources, and peoples there. Some sixteenth-century authors even referred to Mesoamerican religious structures as mosques, revealing the pervasiveness of the Eurocentric conquest attitude they brought with them.

Throughout the sixteenth century, terrible epidemics and the cruel labor practices of the encomienda (Spanish forced labor) system resulted in mass casualties that devastated Indigenous populations throughout the Americas. Encomiendas established throughout these territories placed Indigenous peoples under the authority of Spaniards. While the goal of the system was to have Spanish lords educate and protect those entrusted to them, in reality it was closer to a form of enslavement. Millions of people died, and with these losses certain traditions were eradicated or significantly altered.

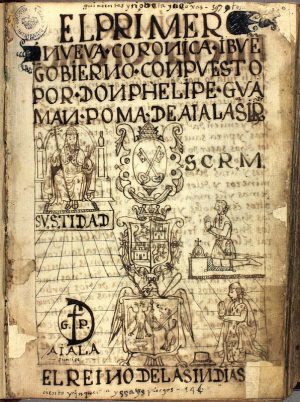

Title page from Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, The First New Chronicle and Good Government, c. 1615 (The Royal Danish Library, Copenhagen)

Nevertheless, this chaotic time period also witnessed an incredible flourishing of artistic and architectural production that demonstrates the seismic shifts and cultural negotiations that were underway in the Americas. Despite being reduced in number, many Indigenous peoples adapted and transformed European visual vocabularies to suit their own needs and to help them navigate the new social order. In New Spain and the Andes, we have many surviving documents, lienzos, and other illustrations that reveal how Indigenous groups attempted to reclaim lands taken from them or to record historical genealogies to demonstrate their own elite heritage. One famous example is a 1200-page letter to the king of Spain written by Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, an Indigenous Andean whose goal was to record the abuses the Indigenous population suffered at the hands of Spanish colonial administration. Guaman Poma also used the opportunity to highlight his own genealogy and claims to nobility.

Talking about Viceregal Art

How do we talk about viceregal art more specifically? What terms do we use to describe this complex time period and geographic region? Scholars have used a variety of labels to describe the art and architecture of the Spanish viceroyalties, some of which are problematic because they position European art as being superior or better and viceregal art as derivative and inferior.

Juan Baptista Cuiris, image of Christ made with feathers, c. 1590–1600, 25.4 x 18.2 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

Some common terms that you might see are “colonial,” “viceregal,” “hybrid,” or “tequitqui.” “Colonial” refers to the Spanish colonies, and is often used interchangeably with “viceregal.” However, some scholars prefer the term “colonial” because it highlights the process of colonization and occupation of the parts of the Americas by a foreign power. “Hybrid” and “tequitqui” are two of many terms that are used to describe artworks that display the mixing or juxtaposition of Indigenous and European styles, subjects, or motifs. Yet these terms are also inadequate to a degree because they assume that hybridity is always visible and that European and Indigenous styles are always “pure.”

Applying terms used to characterize early modern European art (Renaissance, Baroque, or Neoclassical, for instance) can be similarly problematic. A colonial Latin American church or a painting might display several styles, with the result looking different from anything we might see in Spain, Italy, or France. A Mexican featherwork, for example, might borrow its subject from a Flemish print and display shading and modeling consistent with classicizing Renaissance painting, but it is made entirely of feathers—how do we categorize such an artwork?

It is important that we not view Spanish colonial art as completely breaking with the traditions of the pre-Hispanic past, as unoriginal, or as lacking great artists. The essays and videos found here reveal the innovation, adaptation, and negotiation of traditions from around the globe, and speak to the dynamic nature of the Americas in the early modern period.