Essay by Mei Mei Chan

Before the Buddha lived as Prince Siddhartha Gautama, he had already lived through many different incarnations and lifetimes. The Buddha’s soul accumulated much virtue from his many previous lifetimes as various selfless beings. Jataka tales tell of the Buddha’s previous incarnations or past lives and the ways in which he accumulated his good karma through sacrifice. They feature characters who live lives of selflessness and sacrifice.

Prince Mahasattva

A Dunhuang mural depicts a famous Jataka tale about Prince Mahasattva. Painted on the eastern wall of Mogao Cave 428 is a mural of the entire Jataka tale in three registers.

The complete Prince Mahasattva jataka tale mural, Mogao Cave 428, Northern Zhou, 557–581 C.E., Dunhuang (image courtesy of the Dunhuang Academy)

The mural begins on the right-hand side of the first register. Three young men kneel before a blue pagoda with their hands pressed together. Two regal figures sit inside the blue pagoda; they are presumably the king and the queen. They wave farewell to the three young men, who are presumably their sons.

Detail of the three princes hunting in the forest. First register, middle section, Mogao Cave 428, Northern Zhou, 557–581 C.E., Dunhuang (image courtesy of the Dunhuang Academy)

In the next few scenes, the three brothers head off into the forest to go on a hunt. Deer and tigers populate the forest while trees and mountain ranges frame each scene. The undulating, multi-colored mountains are scaled to be smaller than the trees, animals, and human figures.

The story continues on the second register, this time beginning on the left-hand side. The three brothers continue further into the forest when they descend from their horses to take a rest at the base of some mountains.

Detail of the starving tigress and her baby cubs. Second register, middle-left section, Mogao Cave 428, Northern Zhou, 557–581 C.E., Dunhuang (image courtesy of the Dunhuang Academy)

During their rest, the brothers spot a tigress with seven baby cubs. The tigress is depicted with her mouth open and painted in dreary shades with drooping limbs. She stares at baby cubs who prance around her feet. She looks ready to eat her own children. The brothers convene to discuss the matter of the tigress. Not wanting to watch a mother devour her own children, the brothers resolve to help her find food. However, there does not appear to be any food nearby. Prince Mahasattva suddenly comes up with an idea. He keeps it to himself and tells his two brothers to leave the forest to find some food while he stays behind to watch over the tigers. After his brothers leave, Prince Mahasattva strips off his clothes and lies down in front of the tigress, offering himself to the tigress. He decides to offer himself as food for the tigress so that she wouldn’t have to eat her own children. The tigress sniffs at his body but makes no move to harm him even though she is starving.

When we offer help to someone and they are unable to accept what is offered, it’s a chance for us to feel good about having attempted goodness without losing anything. We can think to ourselves, well, we tried to help. In the case of Prince Mahasattva, he understood that good intentions alone would not save a life. It would take determined and complete self-sacrifice to save the tigers.

Detail of the Prince Mahasattva’s sacrifices to the tigers. Second register, right section, Mogao Cave 428, Northern Zhou, 557–581 C.E., Dunhuang (image courtesy of the Dunhuang Academy)

Realizing that the tigers will not eat him alive, Prince Mahasattva climbs to the edge of a cliff, cuts open his neck and throws himself off the ledge. With his neck bleeding profusely, his body drops in front of the tigress and her cubs. At Prince Mahasattva’s second attempt to offer his body, the tigers devour him as nourishment.

Snaking across and down the three registers, the story continues on the third register by beginning on the right-hand side again. Prince Mahasattva’s brothers return and they understand what happened in their absence when they see the bones left behind by the tigress and her cubs.

Detail of the grieving brothers and their return to the palace. Third register, Mogao Cave 428, Northern Zhou, 557–581 C.E., Dunhuang (image courtesy of the Dunhuang Academy)

The brothers’ bodies contort across the scene in shock, anguish, and grief in reaction to the death of their third sibling. The two brothers practically fly back to the palace on their horses to tell the king about what happened to Prince Mahasattva.

Detail of the brothers building a stupa over Prince Mahasattva’s remains. Third register, Mogao Cave 428, Northern Zhou, 557–581 C.E., Dunhuang (image courtesy of the Dunhuang Academy)

The story actually ends on the topmost right corner of this image, returning to the place where the two princes found their brother’s corpse. After reporting to the king, the family builds a stupa over Prince Mahasattva’s bones and hair to commemorate his selfless actions.

Pilgrims circumambulating the Boudhanath stupa, 14th century, Kathmandu, Nepal (photo: Alina Chan, CC BY-SA 4.)

The stupa

A stupa is a sacred Buddhist architectural structure built as a shrine over relics or simply as a place for spiritual meditation. A stupa is a place imbued with strong Buddhist power. People make pilgrimages to famous stupas such as the Boudhanath stupa in Nepal. Worshippers pray at stupas by circumambulating clockwise around the monument.

Many of the Mogao caves at Dunhuang have central pillars that take after the stupa form. Scholars have theorized that worshippers could have circumambulated these central pillars inside the Mogao caves at Dunhuang as one would do around stupas in the open air.

The complete Prince Mahasattva jataka tale mural, Mogao Cave 428, Northern Zhou, 557–581 C.E., Dunhuang (image courtesy of the Dunhuang Academy)

If you look again at the complete image of this Jataka tale, you may notice that this Jataka tale stops abruptly in the middle of the third register. Two white and blue palaces formally frame the narrative painting of Prince Mahasattva like bookends (in the upper right, and midway through the bottom, final, register)— and that’s because in the left corner of the bottom register of the mural there are drawings that depict two other tales.

Detail of the left side of the third register of the Mahasattva jataka painting, Mogao Cave 428, Northern Zhou, 557–581 C.E., Dunhuang (image courtesy of the Dunhuang Academy)

On the left is a scene based on a verse from chapter four of the Dhammapada, a volume known as a collection of the Buddha’s sayings and teachings in Theravada Buddhism. The scene on the right depicts the tale of the seduction of the ascetic Ekaśṛṅga. In a popular Indian jataka tale, Ekaśṛṅga was the child of a female antelope. He was seduced by a courtesan or king’s daughter and lost his supernatural powers.

The inclusion of these scenes demonstrates the pan-Asian spread of Buddhism, a movement facilitated in large part by the Silk Road trade routes.

King Sivi

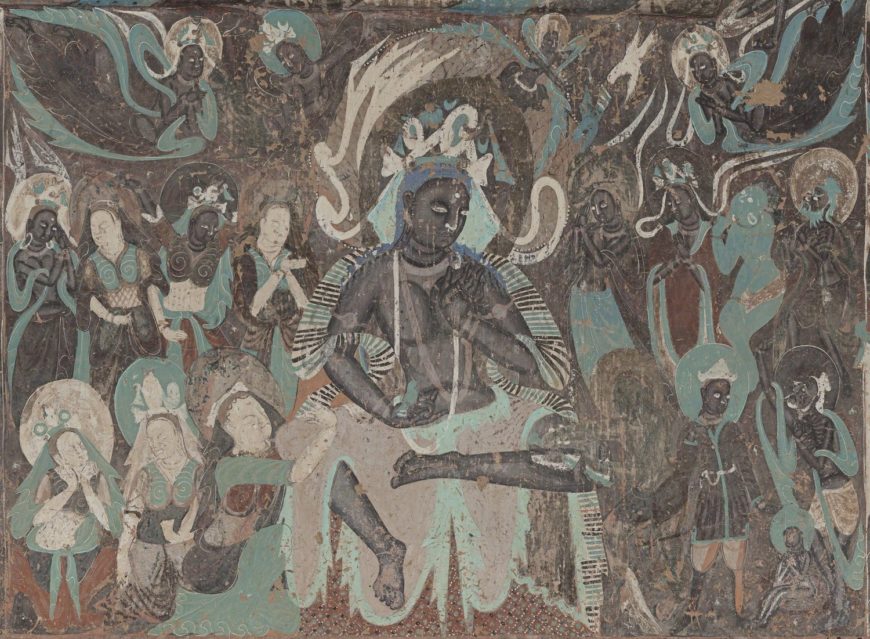

A mural from Dunhuang, Mogao Cave 254, depicts the jataka tale of King Sivi. King Sivi was known for keeping his word and for his selflessness. Two main stories are associated with King Sivi.

Mural of King Sivi holding the dove, from the north wall of Mogao Cave 254, Dunhuang, 439–534 C.E., Northern Wei Dynasty (image courtesy of the Dunhuang Academy)

In the first story, King Sivi thought to himself one day,

If there be any human gift that I have never made,

Be it my eyes, I’ll give it now, all firm and unafraid.

Reading his thoughts, a blind brahmin (an elite caste, that includes priests, scholars, and teachers) came forward to ask for his eyes. Without hesitating and without listening to his ministers’ protests, King Sivi offered the blind brahmin his eyes.

In a second story, King Sivi comes across a dove trying to escape a falcon. King Sivi offered the dove safety. The falcon offered to let the dove go on the condition that he received fresh flesh from the king in equal weight to the dove. King Sivi agreed, and had a butcher slice flesh from his leg to place on a scale to weigh against the dove. But after cutting off more and more flesh, it still was not equal in weight. Finally, King Sivi placed himself on the scale, offering his entire self in return for the dove’s life.

In Mogao Cave 254, King Sivi holds the dove while the butcher slices flesh from his leg. The queen, distraught, clasps his other knee.

Syama

The Syama jataka tale is about one of the Buddha’s previous incarnations as Syama, the filial son who made a point to look after his hermit parents even at his most vulnerable moment in life. One day Syama was fetching water from a river in the forest when the king of Benares accidentally kills him with an arrow. On his deathbed, Syama asked the king to take care of his blind, hermit parents in his stead.

The complete Syama jataka tale mural, Mogao Cave 302, Sui Dynasty, 581–618 C.E., Dunhuang (image courtesy of the Dunhuang Academy)

A mural on the eastern side of the gabled ceiling in cave 302 depicts a continuous narrative painting (telling an entire story in one painting) of the Syama jataka tale.

Detail of the king of Benares going hunting from the Syama jataka tale mural, Mogao Cave 302, Sui Dynasty, 581–618 C.E., Dunhuang (image courtesy of the Dunhuang Academy)

In this section of the mural from Cave 302, the viewer is introduced to the king of Benares who sits under an azurite blue pavilion at his palace and addresses a group of kneeling attendants. The scenes progress to the right as the setting transforms from the palace to the forest.

Sporting an extravagantly red outfit (possibly painted using a red iron oxide pigment), the king waves goodbye to his attendants as he sets off on his royal horse in preparation for his hunt in the forest.

Detail of the king of Benares shooting Syama from the Syama jataka tale mural, Mogao Cave 302, Sui Dynasty, 581–618 C.E., Dunhuang (image courtesy of the Dunhuang Academy)

Ethereal deer frolic between foliage and across this section of the mural, transitioning viewers to the introduction of Syama. Syama quietly crouches beside a flowing stream among the trees to fetch water. He wears deerskins so as not to startle the other woodland creatures.

Detail of the king of Benares descending from his horse after he shoots Syama from the Syama jataka tale mural, Mogao Cave 302, Sui Dynasty, 581–618 C.E., Dunhuang (image courtesy of the Dunhuang Academy)

Camouflaged in the forest, he becomes the unsuspecting target of the king’s arrow. He is caught ladling water when the arrow flies in his direction.

The refreshing hue of the water in the river may be attributed to the bright mineral atacamite, found naturally in many arid regions.

Detail of the dying Syama from the Syama jataka tale mural, Mogao Cave 302, Sui Dynasty, 581–618 C.E., Dunhuang (image courtesy of the Dunhuang Academy)

In this image, Syama is dying. With his last words, he tells the king of Benares about his blind, hermit parents with whom he lives in the forest. He makes a plea to the king to protect them. The viewer can almost hear Syama’s respect and love for his parents in the dignified portrait of the couple who float behind him.

Detail of the king of Benares visiting Syama’s parents from the Syama jataka tale mural, Mogao Cave 302, Sui Dynasty, 581–618 C.E., Dunhuang (image courtesy of the Dunhuang Academy)

In this following section of the mural, the king makes a humble visit to Syama’s parents to tell them what happened to their son. He leads their distraught figures to Syama’s body by the river.

Detail of Syama’s mourning parents from the Syama jataka tale mural, Mogao Cave 302, Sui Dynasty, 581–618 C.E., Dunhuang (image courtesy of the Dunhuang Academy)

Sobbing, Syama’s parents embrace the body of their only child. The father holds Syama by the head while the mother holds him by his legs. The grieving parents swear aloud that if the heavens knew of Syama’s love for them, he could probably come back to life.

Detail of Indra from the Syama jataka tale mural, Mogao Cave 302, Sui Dynasty, 581–618 C.E., Dunhuang (image courtesy of the Dunhuang Academy)

At that moment, the guardian deity Indra flies down from the heavens holding a jar of medicine.

Detail of the reunited family from the Syama jataka tale mural, Mogao Cave 302, Sui Dynasty, 581–618 C.E., Dunhuang (image courtesy of the Dunhuang Academy)

Moved by the king’s penitence and the hermit parents’ grief, the gods restore Syama to complete health. The final scene in the Dunhuang mural depicts Syama’s return to the world of the living and joyful reunion with his parents.

As demonstrated by the stories above, jataka tales often impart a moral lesson or shared cultural values. They detail the Buddha’s past lives and gradual accumulation of good karma in ways that resonate with listeners both in the past and today.

Originally posted on the Dunhuang Foundation blog (Prince Mahasattva, King Sivi, and Syama)