The Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, designed by architect Peter Eisenman and engineer Buro Happold, 2003–04, Berlin, Germany (photo: Wolfgang Staudt, CC BY 2.0)

The genocide that overtook Europe’s Jews transformed Jewish identity throughout the world. Jews in Poland, Romania, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Greece, Yugoslavia, Germany and Austria were reduced to a tiny fraction of their prewar numbers. Even still, Jewish populations survived throughout Europe, including in Russia, the United Kingdom, and France.

Western European nations received substantial aid from the American government, and the Jewish populations in those areas relied on American Jewish organizations for help. The geographic centers of Hasidism in Eastern Europe were disproportionately destroyed during the Holocaust, but many sects continue to thrive on almost every continent. In 1948 the United Nations unanimously voted for an independent State of Israel (the area was at that time under British administration).

Reuven Rubin, First Fruits, 1923, oil on canvas, 188 x 406 cm (The Israel Museum, Jerusalem)

Aftermath

In the immediate aftermath of the war in Eastern Europe, the Soviets continued to downplay the role of race, as they had during the Holocaust, but while many Jews were devoted Communists, they were once again targeted as a suspicious people who could never truly be trusted comrades. Especially during the Soviet show trials in the 1950s and 1960s, Jews were purged from government ranks and executed in public spaces. Although Stalin voted for the creation of Israel in 1948, these public show trials served as “a form of public-pedagogy-by-example;” the goal was to exemplify the fact that ethnic Jews did not belong among the Communist ranks, that they were not equal with others. Even in the secular Soviet Union, overt antisemitism persisted during the Cold War decades. Many Jews made their way out from behind the iron curtain toward Western Europe, Israel, or the United States.

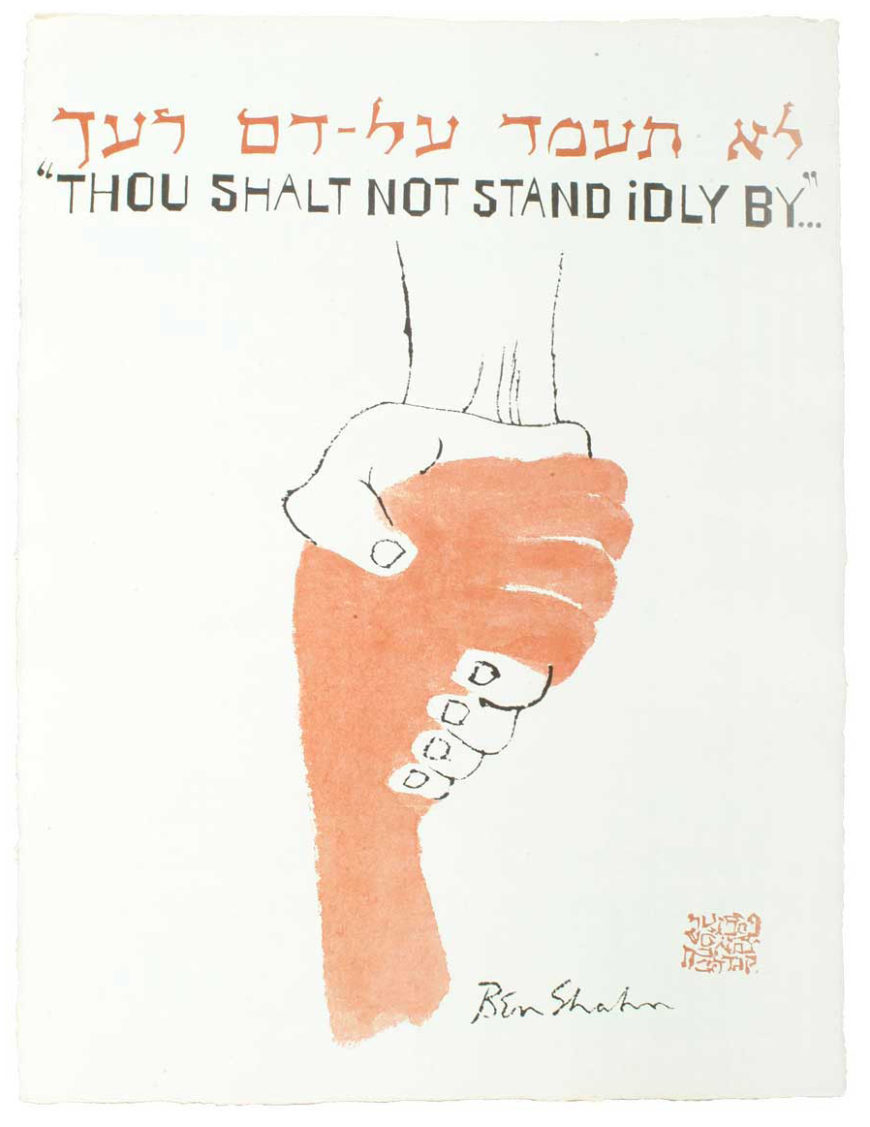

Ben Shahn, “Thou Shalt Not Stand Idly By” from Nine Drawings by Ben Shahn, 1965, photo-offset lithograph, New York, 22 1/16 x 16 15/16 inches (Spertus Institute for Jewish Learning and Leadership, Chicago)

American Jews in the 1950s followed the patterns of other white ethnic immigrant populations. Many left large cities, focused on education, and joined counter-cultural movements in the late 1960s and 70s. American Jews often stood at the side of the oppressed, figuring prominently in the 1960s civil rights movement.

Meanwhile, Jews in Islamic lands emigrated from North African and Middle Eastern countries between the late 1940s and late 1960s when pan-Arab nationalism became exclusively Muslim and precluded participation from others. These Jews immigrated to Israel, Western Europe, and the United States. In France, the Sephardic population from Algeria, Morrocco and Tunisia brought new religious life and diverse customs to a community that was struggling after the trauma of World War II.

Jewish identity now

In the modern world, Jewish identity can seem scattered, confusing, and boundless. In the United States, Jews thrived in the postwar decades and several different movements gained popularity: Orthodox, Conservative, Reform, and Reconstructionist. In Europe and Israel, inspired by these American movements, a smaller fraction of progressive Jews have formed Liberal or other kinds of Judaism. From the 1990s to the present, some American Jews have joined in a worldwide trend toward religious extremism. At the same time, the Reform movement has grown. The traditional separation between men and women has been broken down and women are now integrated into the rabbinate in non-Orthodox circles.

Art Spiegelman, the artist and author of Maus, recently reflected, “One thing that’s become questionable to me is the way in which the Holocaust has become a central tenant of Jewishness in the late 20th century…. So that people see it as a Jewish problem and not a world problem.” The omnipresence of Holocaust education within the Jewish community combined with a sort of alienation from tradition, made the Holocaust into the unifying agent that brought Jews together. In the twenty-first century, young Jews have pushed against the Holocaust as the defining feature of their Jewishness and have sought out alternative ways to express their connections to Judaism. Jewish film, music, and cultural festivals abound, attracting Jewish and non-Jewish audiences. The largest such festival occurs annually in Poland and draws tens of thousands from across the globe—that this festival takes place in the country where the greatest number of Jews were massacred during the Holocaust, signals a turn away from that dark period as the benchmark of Jewish identity and toward new forms of Jewish expression.

Mel Bochner, The Joys of Yiddish, 2012, oil and acrylic on canvas (The Jewish Museum, New York)

One popular joke says that Jews believe in “at most” one God. While monotheism is an important feature of Judaism, some of the greatest Rabbis from the Talmud have atheist tendencies, even as they espouse the centrality of Halakhah. As the scholar Shaye J.D. Cohen has written, “Jewishness, like most—perhaps all—other identities, is imagined; it has no empirical objective, verifiable reality to which we can point and over which we can exclaim, ‘This is it!’ Jewishness is in the mind.”

Lacking any unifying authority, doctrine, or practice, Judaism is highly diverse and cannot be pared down to any singular concept. Instead, a set of features like common texts, a shared history, and the rhythms of religious Jewish life can help us understand a religion shaped as much by its ancient origins as its contemporary disjointedness.