Flags of South Korea flying on National Liberation Day of Korea (photo: Korea Culture and Information Service, CC BY 2.0)

It is undeniable that national flags have become an indispensable part of our lives yet they are rarely taken as serious topics of art history. Nevertheless national flags are richly condensed with the history of a country’s politics, society, and culture—making them crucial visual imagery to be investigated. Visual symbols like national flags are central contributors to the formation of modern nation-states and the contemporary system of international relations, not only helping to differentiate individual countries, but also embodying collective identities.

The national flag of South Korea is named Taegeukgi (태극기, 太極旗). The flag has a red and blue Taegeuk symbol in the center, with sets of paired black lines called trigrams in each of the four corners of a white background. This flag was first created in the early 1880s by Joseon (1392–1897) state officials when Joseon Korea first forged diplomatic relations with Western nation-states. Korea had no national flag previously. The creation of the Taegeukgi was intended to represent Korea as a modern, sovereign nation-state at the turn of the twentieth century.

The central Taegeukgi design stems from ancient East Asian visual representations of the supreme forces of the universe and symbolizes the concept of harmony in the cosmos. The blue Taegeuk represents the negative forces of the universe (eum, 陰) and the red Taegeuk the positive (yang, 陽). According to tradition widely recognized in East Asia, the harmony of these two forces give life to all things in the universe and represent the ultimate truth of the great natural world.

“Inkstone” and cover in the shape of a turtle, with the 8 trigrams used in Daoist cosmology on the turtle shell, 6th–7th century, earthenware, China, 8.9 cm x 23.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Trigrams are composed of three lines that are either whole or broken and each trigram is affiliated with different components that make up the universe. They were often used as a set of eight in Daoist traditions and were frequently used for divination, influenced by the popular Confucian classic, Book of Changes (or I-Ching, 역경, 易經). The eight trigrams, such as we see in a 6th- or 7th-century earthenware turtle, are some of the earliest images associated with Daoism. Each of the four trigrams used on the Korean flag has a name: the geon (건, 乾), gon (곤, 坤), gam (감, 坎), ri (리, 離). In the Taegeukgi design, geon symbolizes the sky, gon represents the earth, gam stands for water, and ri for fire.

Taegeukgi-style processional flag (Jwadokgi, 좌독기, 坐纛旗), 19–20th century, silk, 121 x 150cm (National Palace Museum of Korea)

The Taegeuk and trigrams were widely used in East Asian cultures in slightly varying forms as auspicious motifs. In the Joseon dynasty, the Taegeuk and eight trigrams were also employed as one of the many processional flags that represented monarchical authority and symbolized the king’s harnessing and understanding of the harmonious spirit or energy of the cosmos. The traditional flag design was reinterpreted at the turn of the twentieth century to suggest the collective Korean nation-state and its identity.

Historical background and two theories of creation

The Joseon dynastic kingdom first experienced modern flag-bearing customs in 1875 during the Ganghwa Incident. Despite the unauthorized sailing and docking of the Japanese ship on Korean territory, Japan demanded compensation and claimed that the Joseon military deliberately and illegally attacked the state-sanctioned vessel bearing the Japanese flag. The apparent failure of the Joseon state to recognize modern diplomatic customs of flag-bearing gave Japan justification to demand official indemnification (compensation for harm or loss) and the signing of the Ganghwa Treaty in 1876 that opened Joseon ports to Japan. From this incident, the Joseon government was made to realize the importance of national flags as critical components in modern international relations and the pressing need for a Korean national flag.

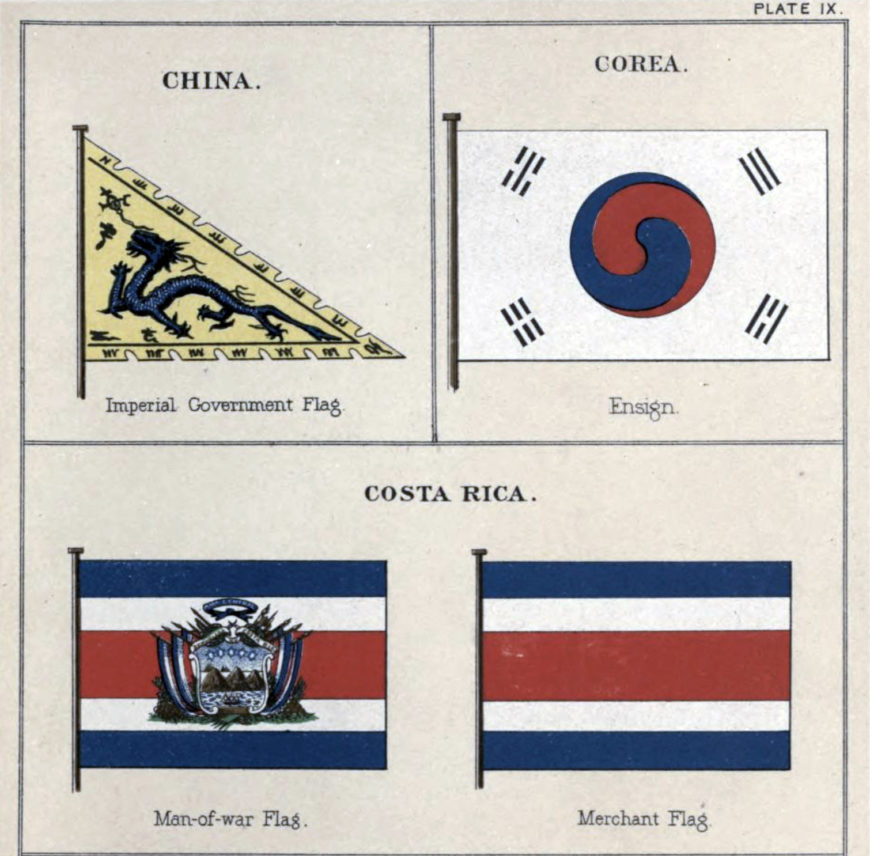

Detail of a plate showing the national flags of China and Korea in 1882. Bureau of Navigation, Flags of Maritime Nations: From the Most Authentic Sources, 5th ed. (Washington D.C.: Bureau of Navigation, 1882)

Faced with the establishment of official diplomatic relations with Western nations, the Taegeukgi was created in 1882 and made the national flag in 1883. It served many different functions, such as differentiating and representing Korea among other nation-states of the world, symbolizing the Korean state and its authority, and in inducing collective identification with the flag as a visual manifestation of Korean nationhood.

Taegeukgi of the 1880s–1910s

The Taegeukgi was first used by the Joseon state to represent Korea in international arenas from the 1880s. From the 1890s, the Taegeukgi was used in nation-building projects. The Taegeukgi was also used among Korean independence activists after Japanese annexation and throughout the colonial period (1910–45). The 1880s to the 1910s was a crucial period when the Taegeukgi was consolidated as a Korean national flag both abroad and at home. Prior to this, the Joseon state had relied on Chinese symbols to visualize monarchical authority and cultural conformity to Sinocentrism.

Qing China chose the traditional five-clawed “dragon flag”—long associated with Chinese imperial authority—as its national flag (as seen in the Flags of Maritime Nations book plate shown above). Traditionally, Joseon had used the four-clawed dragon flag in processions that represented the king’s authority. Upon selecting a new national flag design, Chinese officials made repeated suggestions for Joseon to adopt the four-clawed dragon flag as it visually consolidated Qing-Joseon tributary relations. The conscious decision to reject the dragon flag for the Taegeukgi signaled Korea’s departure from the traditional Sinocentric world order.

Jouy Taegeukgi, 1884 (Smithsonian Institute)

The earliest surviving example of an actual flag of Korea is thought to be the so-called Jouy Taegeukgi, collected by American visitor Pierre Louis Jouy in Korea circa 1884. On it, the central Taegeuk symbol is large and has four relatively small, thin black trigrams closely positioned to the Taegeuk. This characteristic is commonly found in earlier Taegeukgi examples produced in the 1880s and 1890s.

Denny Taegeukgi, c. 1890 (National Museum of Korea)

Interestingly, there are several variations of Taegeukgi designs at the turn of the twentieth century, as the so-called Denny Taegeukgi design shows. The lack of clear and legal standardized guidelines of the national flag design reveals the contemporary struggle of the Korean government to fully comprehend and execute modern national flag customs. Nevertheless, owing to the relatively distinct design of the Taegeukgi, varied designs were effectively recognized as the national flag of Korea.

Left: Taegeuk 5 penny stamp, 1895 (National Folk Museum of Korea); right: Passport, 1904 (National Palace Museum of Korea)

Even with this inconsistency in design, from the 1880s to the 1910s, the Taegeukgi was used for state branding on newly introduced, modern objects such as postage stamps, trams, court automobiles, and passports to symbolize the authority of the Korean government.

Image from a textbook: “Georeum” (거름/걸음, The March) in Choesin chodeung sohak 최신초등소학 最新初等小學 1908, vol.2, retreived from Hangukhak munheon yeon-guso 한국학문헌연구소, Hanguk gaehwagi gyogwaseo chongseo 한국개화기교과서총서 韓國開花期敎科書叢書, vol. 5 (Seoul: Asea munhwasa 아세아문화사 亞細亞文化社, 1977), 247, National Library of Korea.

As the use of print media in nation-building grew in Korea from 1905, illustrations of the Taegeukgi in textbooks were also used to educate the Korean public of modern systems of displaying patriotism and self-identification via the nation-state through flag-waving and saluting the national flag. These new customs were practiced in public events led by not only the state but also nationalistic intellectuals and civil groups who took it upon themselves to edify the Korean public and develop Korea into a modern country in face of foreign invasion.

The Independence Arch, constructed in 1897, photographed after 1945 (National Museum of Korean Contemporary History)

The adoption of such modern flag culture for nation-building in the late 1800s was greatly motivated by political interests to secure Korean independence from China and Japan. Visually separating the newly established Korean Empire (1897–1910) from pre-modern Sinocentrism was emphasized from the 1890s and the Independence Arch was decorated with the Taegeukgi. However, from 1905 to 1910, the Korean government had already lost much of its autonomy and authority, leaving the burden of public education, modernization, and nation-building to non-state actors (intellectuals who didn’t work in office or groups and organizations composed of such individuals) who emphasized the Taegeukgi as a symbol of the collective Korean nation-state and national identity rather than the narrower Korean state and its authority.

After the Japanese annexation of Korea in 1910, independence activists primarily used the Taegeukgi as a symbol of resistant nationalism against Japan. The absence of a sovereign Korean state under colonial occupation amplified the association of the Taegeukgi with the Korean people and their shared national identity, which differentiated the Taegeukgi from traditional Joseon’s dynastic processional flags that expressed the power of the monarch. After liberation from Japan in 1945 and the establishment of the South Korean government in 1948, the Taegeukgi came to represent not only the government but also the shared history of the South Korean people.

Jin-gwansa Temple Taegeukgi, c. 1919, housed at Jin-gwansa Temple (Korean Cultural Heritage Administration)

Despite such widespread application of the Taegeukgi as a Korean national flag from the 1880s to the 1910s, there was no official standardization of its design until the establishment of the South Korean government. Although the style of the Taegeukgi design greatly varied throughout the 1880s to the 1940s, the Korean national flag represented an autonomous country from China, a unified collective nation capable of socio-political reform and participation in world politics, and the Korean people’s will to resist Japanese occupation and fight for independence.