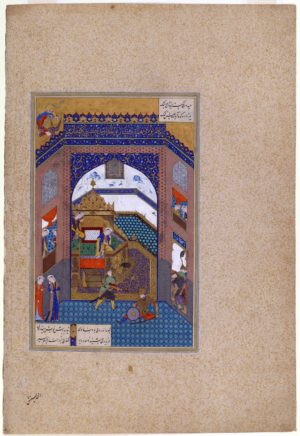

“The Bier of Iskandar (Alexander the Great),” folio from the Great Mongol Shahnama (Il-Khanid dynasty, Tabriz, Iran), c. 1330, ink, opaque watercolor and gold on paper, 57.6 x 39.7 cm (National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Illustrated manuscripts are one of the glories of Persian art, especially those made during the heyday of production from the 14th century to the 16th century. The most popular text was the Shahnama, or Book of Kings. This 50,000-couplet poem recounts the history of Iran from the creation of the world to the coming of the Arabs in the 7th century through the reigns of fifty successive monarchs. Rulers and their courtiers often commissioned splendid copies of the Shahnama to link themselves to the heroes of the past, whether the “Alexander of the Age” or “The Lord of the World.”

Today some of the most important manuscripts are sadly dismembered. Reconstructing the history of two of these splendid manuscripts—from creation to mutilation—shows how they have been used (and misused) over the centuries as political propaganda, loot, and even fodder in the international art market.

Attributed to Sultan Muhammad, “The Court of Kayumars,” from the Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp I, c. 1524–25 (Safavid, Tabriz, Iran), opaque watercolor, ink, gold, silver on paper, folio 20 verso, 47 x 32 cm (Aga Khan Museum, Toronto; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Great Mongol Shahnama and the Tahmasp Shahnama

These two illustrated pages (above) come from the most ambitious manuscripts known: the Great Mongol Shahnama, made for the Mongol court in northwest Iran around 1330, and the Tahmasp Shahnama, made two centuries later in the same region for the Safavid shah Tahmasp (and perhaps inspired by the earlier one).

Attributed to Sultan Muhammad, “The Lord of the World” shown as part of “The Court of Kayumars,” from the Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp I, c. 1524–25 (Safavid, Tabriz, Iran), opaque watercolor, ink, gold, silver on paper, folio 20 verso, 47 x 32 cm (Aga Khan Museum, Toronto; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Large books with hundreds of illustrations

Both of these manuscripts are very large books. The 759 folios, or leaves, in the Tahmasp Shahnama measure 47 x 32 cm with a whopping 258 illustrations, many of them nearly full size and sometimes spilling into the gold-sprinkled margins. The Great Mongol Shahnama was even larger: it had around 300 folios with some 200 illustrations, most about half or two-thirds the area of the written surface. [1] Both projects must have taken a decade to complete, even with a workshop of papermakers, calligraphers, painters, illuminators, binders, and other craftsmen.

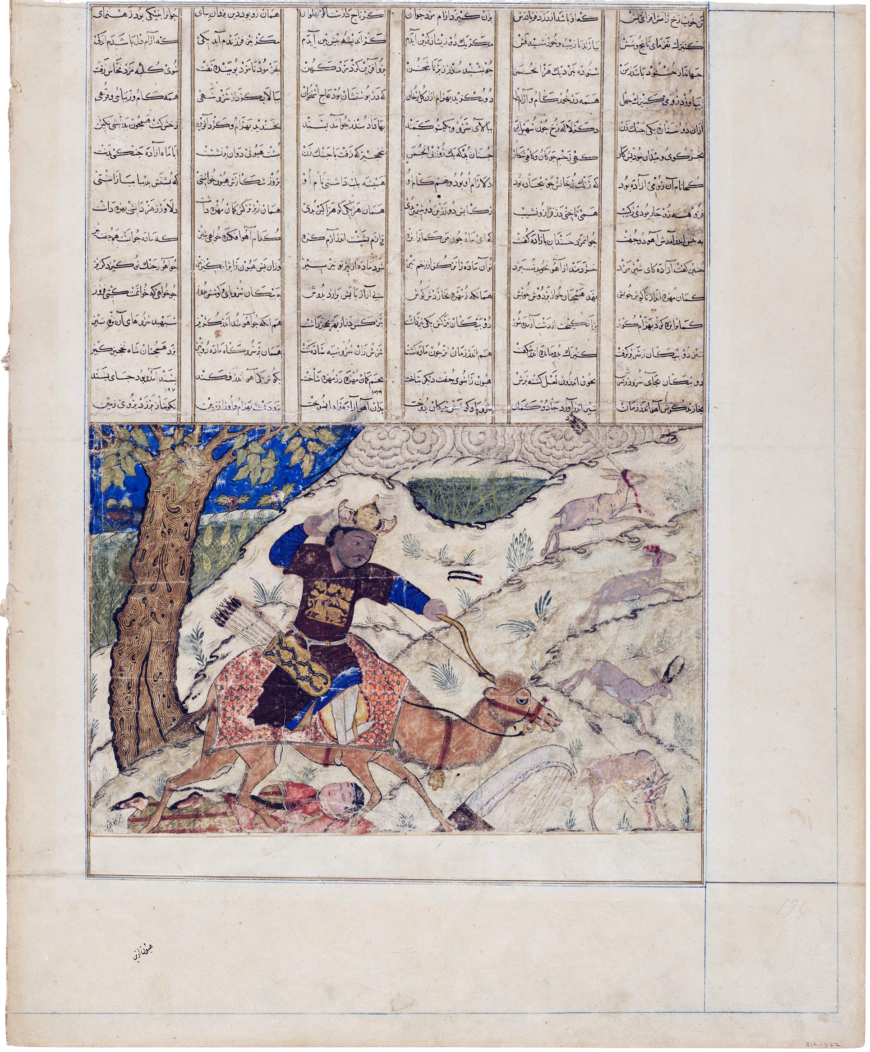

Photograph taken by Antoin Sevruguin in Tehran showing the illustration of “Bahram Gur Hunting with Azada,” within the bound Great Mongol Shahnama, 1880–1910 (National Museum of Asian Art Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.)

Both manuscripts became part of the royal library, a necessary accoutrement of a cultured prince from the 14th century onwards in Persia and elsewhere. The Great Mongol Shahnama seems to have stayed there until the 19th century when the manuscript, perhaps unfinished or damaged, was repaired: some of the faces in the paintings were retouched with pink cheeks and heavy eyebrows typical of the 19th-century Qajar style, the folios were numbered and remargined on imported Russian paper dated 1832, and the original two volumes were conflated into one. A photograph taken in Tehran at the end of the 19th century by the Armenian photographer Antoine Sevruguin shows the bound volume open to one of the illustrated pages.

Painting of “Bahram Gur Hunting with Azada” from the Great Mongol Shahnama. By 1931, Georges Demotte had sold this folio from the Great Mongol Shahnama to Edward W. Forbes, director of the Fogg Museum at Harvard University (Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Cambridge, MA)

The Tahmasp Shahnama is given to an Ottoman sultan

The Tahmasp Shahnama had a different trajectory. It remained prized at Tahmasp’s court for a few years, as the court librarian Dust Muhammad extolled its painting of “The Court of Kayumars” in an album preface written in 1544, and two illustrated folios were replaced for unknown reasons. But then in 1566 Tahmasp, who had apparently tired of painting and dispersed his royal workshop, decided to give the manuscript to the Ottoman sultan Selim II to mark his succession. Tahmasp sent the Shahnama at the head of a long camel train along with a Qurʾan manuscript attributed to the hand of Prophet’s son-in-law ʿAli ibn Abi Talib, books chosen to emphasize the shah’s royal and religious pedigree and show up his rival as a mere parvenu.

Nakkaş Osman, “Presentation of Gifts by the Safavid Ambassador, Shahquili, to Sultan Selim II at Edirne in 1568,” from Seyyid Lokman, Şehname-I Selim Han, 1581 (Topkapi Palace Library, Istanbul, A3595, folio 53b–54a)

The Ottomans got the message, and their reception of the embassy and its gifts was just as orchestrated. They produced their own richly illustrated dynastic histories, including one with a painting showing the enthroned Selim loftily accepting the gifts from groveling ambassadors as a form of entitled tribute rather than an exchange between equals.

Commentaries by Mehmed ʿArif Efendi, added on a separate sheet and pasted into the Tahmasp Shahnama (opposite the painting of “The Angel Surush rescues Khusraw Parviz,” attributed to Muzaffar ‘Ali), from the Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp I, c. 1530–35 (Safavid, Tabriz, Iran), opaque watercolor, ink, silver, and gold on paper, 47.3 x 31.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

The Ottomans sequestered the Tahmasp Shahnama in their royal library. It may have been examined occasionally, as details of the Safavid paintings are occasionally repeated in Ottoman manuscripts, but the lack of fingerprints, smudges, creases, and other marks show that few people consulted the volume. One exception was Mehmed ʿArif Efendi, keeper of guns at the court treasury, who added synoptic commentaries about the paintings in Ottoman Turkish in 1800–1801. Written on polished sheets that were glued into the manuscript opposite the illustrated pages, these synopses suggest that readers at the Ottoman court, which by this point used Ottoman Turkish, merely flipped through the Persian text, looking only at the paintings.

By 1931, Georges Demotte had sold this folio from the Great Mongol Shahnama, photographed bound in the manuscript in Tehran in the 19th century, to Edward W. Forbes, director of the Fogg Museum at Harvard University. Folio from the Great Mongol Shahnama with “Bahram Gur Hunting with Azada,” c. 1335 (Il-Khanid dynasty, Tabriz, Iran), ink, opaque watercolor and gold on paper, 49.3 x 40.2 cm (Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Cambridge, MA)

Cutting up the Great Mongol Shahnama

The situation for these and many other illustrated manuscripts changed dramatically at the turn of the 20th century with political upheavals in the Islamic lands and the growing power of Europe and the art market there. Impoverished courtiers apparently filched manuscripts from royal libraries and sold them to European and American dealers and collectors who had developed a taste for richly illustrated texts. The Tahmasp Shahnama was the first of the two manuscripts to go. By 1903 it had moved, perhaps via Iran, to Paris where it entered the collection of Baron Edmund de Rothschild.

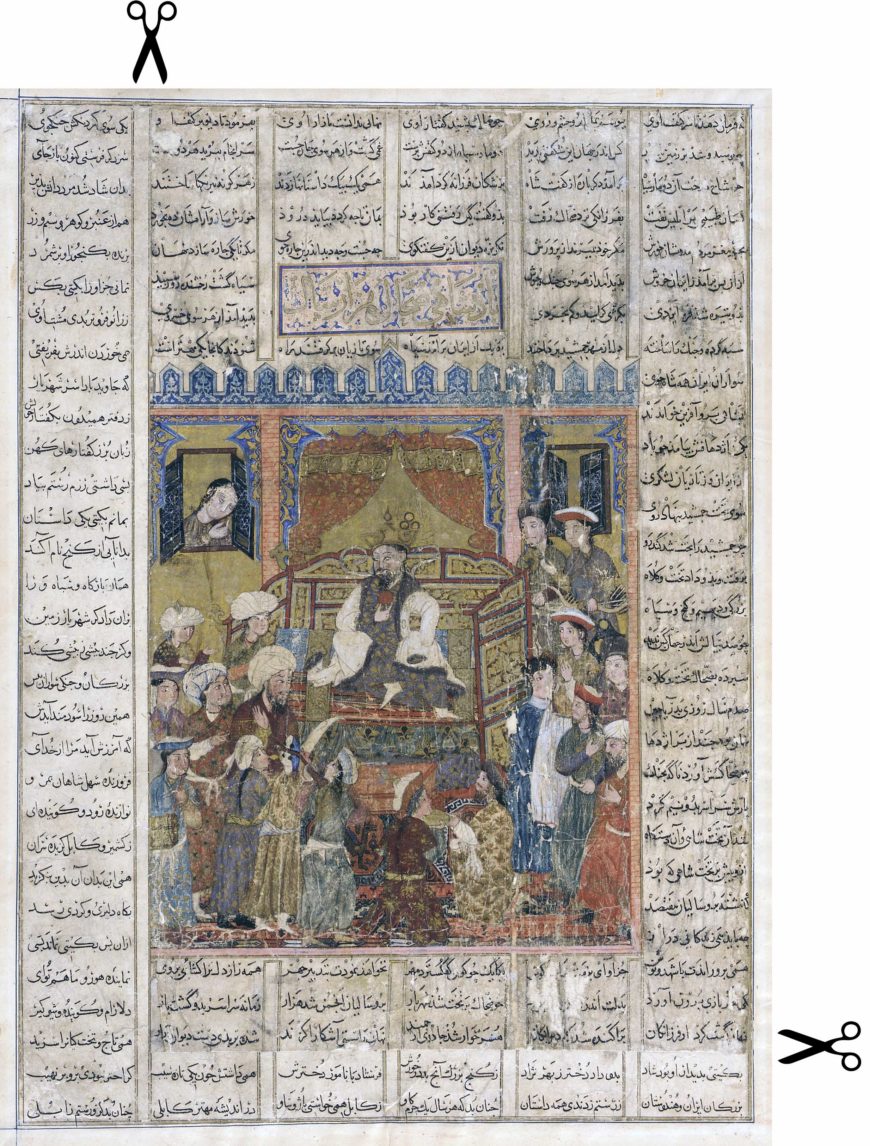

A page from the Great Mongol Shahnama that has been abraded while being split from the original reverse side of the folio. It is now pasted into a page with text from another part of the epic (scissor icons indicate the edges of the top sheet of paper). It was purchased from Demotte, Inc in 1923. “Zahhak Enthroned,” from the Great Mongol Shahnama, c. 1330–40 (Il-Khanid dynasty, Tabriz, Iran), ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper, 24.3 x 19.7 cm (National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institute, Washington, D.C.)

The Great Mongol Shahnama left a few years later, and by 1910 it was in the hands of the Belgian collector Georges Demotte. Unable to sell the whole manuscript, perhaps because of the looming threat of war in Europe, Demotte decided to cut it up and hawk the folios separately to collectors who could display them framed, hanging on the wall. Demotte was faced with a problem, however, as some folios had paintings on both sides.

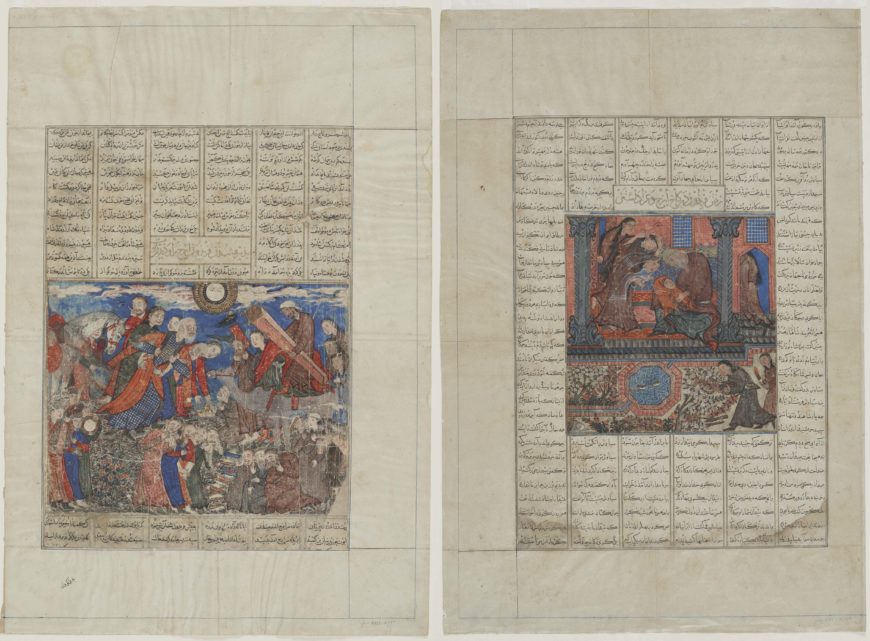

These two paintings were originally on different sides of the same folio. To maximize his profits, Demotte pulled the folio apart and in doing so damaged the pages. The page on the left, much abraded but intact, is now pasted to a back side with unrelated text about Kay Khusraw’s war. The painting shown on the right has no original text around it and is now pasted onto a folio with irrelevant text about Siyâvash. Left: “Faridun mourns the coffin of his son Iraj,” from the Great Mongol Shahnama, c. 1330–40 (Il-Khanid dynasty, Tabriz, Iran), ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper, 59.5 x 40 cm (National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institute, Washington, D.C.); right: “Faridun goes to Iraj’s palace and mourns,” from the Great Mongol Shahnama, c. 1330–40 (Il-Khanid dynasty, Tabriz, Iran), ink, opaque watercolor and gold on paper, 59.3 x 40.1 cm (National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institute, Washington, D.C.)

To maximize his profits, he had the two sides of the folio pulled apart and then remounted the pages separately (such as “Zahhak enthroned” and “Faridun mourning his son”) or had the detached paintings pasted onto other folios (such as “Faridun goes to Iraj’s palace and mourns”).

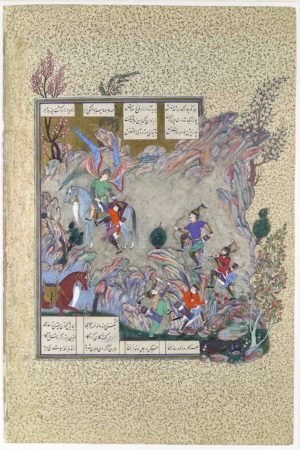

One of the original 76 folios from the Tahmasp Shahnama that Houghton donated to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1970. Folio 708b showing “The Angel Surush rescues Khusraw Parviz,” from the Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp I, c. 1530–35 (Safavid, Tabriz, Iran), attributed to Muzaffar ‘Ali, ink, opaque watercolor, silver, and gold on paper, 47.3 x 31.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

In doing so, he damaged some of the pages. Many of them are abraded because of the paper sheets that were temporarily glued on to help separate the two sides of the folio. In a few cases, parts of the folio, including the painted area, were damaged. Some entire pages or folios may have been destroyed. All together, Demotte is known to have sold 58 illustrated folios and a handful of text folios that were attached to them so that collectors could frame a double-page spread to resemble an open book. The rest of this magnificent manuscript, with some of the most emotional scenes ever produced in Persian painting, is missing, likely destroyed.

The dispersal of the Tahmasp Shahnama

The Tahmasp Shahnama again followed a different course. Two years after the death of Baron Rothschild’s son Maurice in 1957, the manuscript, intact with all of its 258 paintings, was sold to the American magnate and bibliophile Arthur A. Houghton, Jr. who commissioned the American scholars Martin Dickson and Stuart Cary Welch to prepare a lavish monograph that reproduced all 258 illustrated pages at full size. To make the plates for publication, the volume had to be unbound, a step that presaged its dispersal.

Small groups of paintings, now framed in silk mats, were exhibited starting in 1962 at the bibliophilic Grolier Club in New York, of which Houghton was president. At this time the international art market was heating up, and works of Middle Eastern, particularly Persian, art were in high demand. Empress Farah of Iran was a major collector, and texts like the Shahnama that reflect the glories of Iranian kingship were particularly popular in this imperial era. Houghton, who was in the midst of divorcing his third wife and marrying his fourth, began to auction off his rare books. In 1970 when The Metropolitan Museum of Art celebrated its centennial, Houghton, then chairman of the board, donated 76 illustrated folios from the Tahmasp Shahnama to it. He needed to establish a tax basis for his donation, and beginning in 1976, individual folios appeared for sale on the market. The first seven comprised works by all the major painters that Dickson and Welch assigned to the manuscript, thereby establishing a unit price for works by different hands.

Folio from the Tahmasp Shahnama that was sold in 1977 to the British Rail Pension Fund and then resold at auction in 1996 to the Freer Gallery of Art. “Faridun strikes down Zahhak,” from the Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp I, c. 1525 (Safavid, Tabriz, Iran), ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper, 27.2 x 17.4 cm (National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institute, Washington, D.C.)

More sales followed, some to connoisseurs like Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan who acquired what is regarded as the finest painting in the manuscript, “The Court of Kayumars,” but others (such as “Faridun strikes down Zahhak”) went to investors such as the British Rail Pension Fund.

The manuscript’s peregrinations did not end there. Following the Iranian Revolution of 1979, the art market changed and uproar over the manuscript’s crass dismemberment increased. After Houghton’s death in 1990, his son decided to sell intact the carcass of the manuscript, including its binding and 118 remaining paintings. Complex negotiations through the London dealer Oliver Hoare led to an arrangement in 1994 with the Museum of Contemporary Art in Tehran to trade the manuscript’s remains for a 1953 Willem de Kooning painting, Woman III, a large oil of a standing nude purchased by Empress Farah but considered distasteful in the Islamic Republic. In a scene worthy of a Graham Greene thriller, the trade-off took place one rainy night on the tarmac of Vienna airport. The manuscript, disbound and deprived of its finest paintings, returned to its homeland where it was fêted as a national treasure.

Reconstructing the manuscripts today

It is impossible to undo the damage suffered in dismembering these manuscripts, but scholars have pursued several strategies to help us appreciate some of their original glories. Each approach brings different benefits, but also entails certain limitations. Exhibitions of disbursed folios allows viewers to compare folios side by side, especially important in the case of the Great Mongol Shahnama in which the individual paintings differ so widely. But some museums are prohibited from lending, and few would risk sending all of their folios from one manuscript at a single go.

Another approach is to produce a handsome monograph with full-size color illustrations of all the folios, as Sheila Canby did with the Tahmasp Shahnama to celebrate the poem’s millennium in 2010. [2] The book showcases the wonders of the images, but privileges paintings over poetry and downplays the manuscript as the integral work of art. Calligraphers, heirs to two centuries of tradition in transcribing this text, wanted to have the lines describing the action frame the painting. To do so, they manipulated the layout.

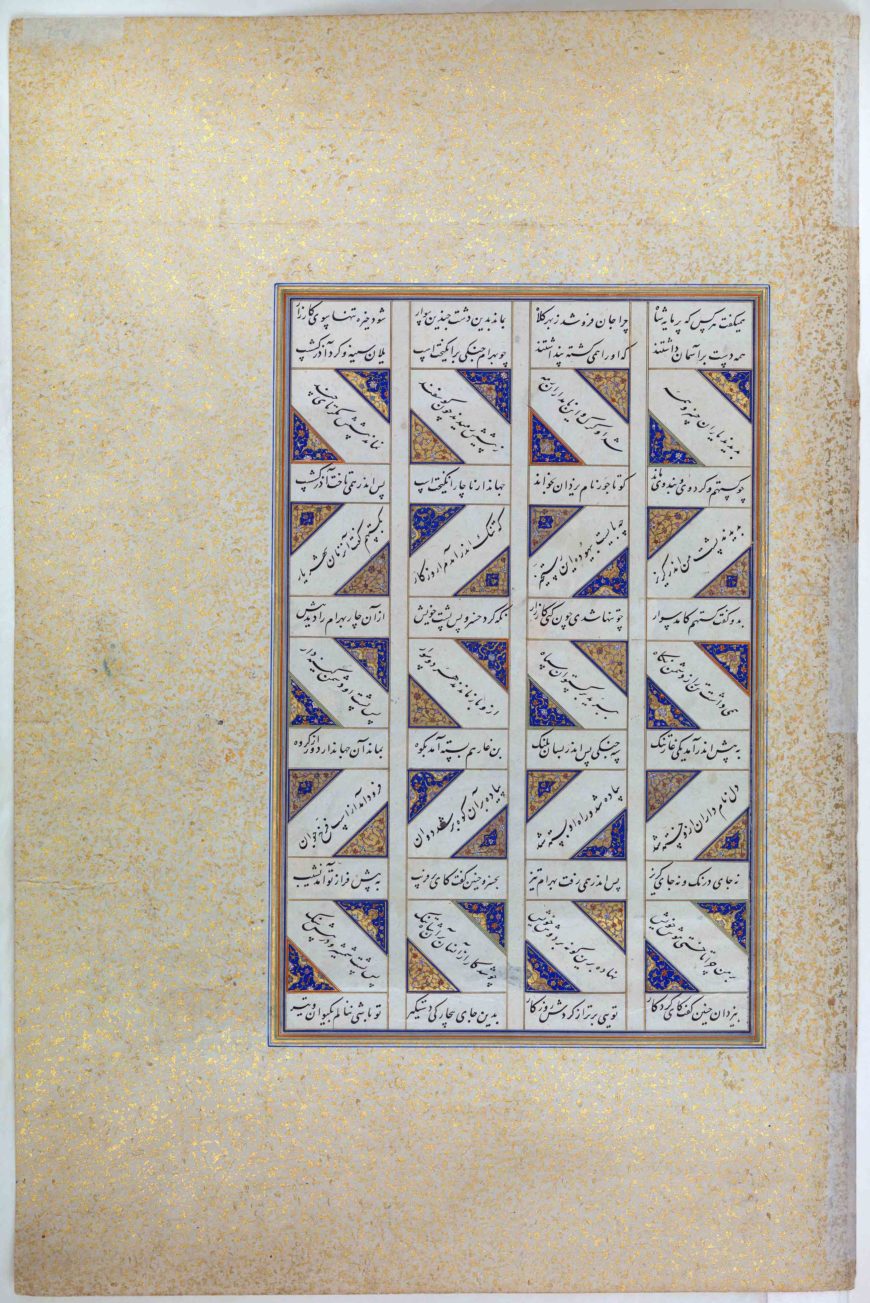

Folio 708a, front side of the folio with “The Angel Surush rescues Khusraw Parviz” shown above. The calligrapher needed to stretch out the text and wrote some of the lines on the diagonal so that the appropriate verses fell around the painting on the back side of the folio (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

In the case of the “The Angel Surush rescues Khusraw Parviz,” for example, the calligrapher wrote some of the lines on the front side of the folio diagonally so that the page contains only 12 lines of text instead of the standard 22, and the couplets describing the angel’s descent fall next to the painting on the reverse. The diagonal layout signals to readers that an illustration is approaching and heightens their anticipation in turning the page.

A digital reconstruction of the manuscript would allow the reader to sense the rhythm while flipping the pages, but such an enterprise is exceedingly difficult given that this manuscript is divided between two major institutions in the U.S. and Iran, with additional folios scattered among dozens of public institutions and private collectors, with some still changing ownership. Furthermore, books in the Islamic lands were never meant to be seen flat, as the bindings allow them to be opened only 110 degrees. Instead, books were read three-quarters open while supported on a cradle or stand. So images of a two-page spread flat on a computer screen directly in front of viewers are distorted and do not convey the original aspect of reading the book. Nevertheless, all of these approaches help us to visually reconstruct these glorious illustrated books, in the words of the Safavid chronicler Dust Muhammad, the likes of which the celestial spheres have never seen.