Treasury, basilica of San Marco, Venice (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The church of San Marco in Venice, Italy holds a treasure trove of artworks and other objects made of precious materials and lavishly decorated with gems, pearls, and enamels. But while many of these objects have sat in San Marco for centuries, not all of them originally come from Venice or even Italy, as their Greek inscriptions suggest. Instead, several objects in the treasury of San Marco were produced in the Eastern Roman “Byzantine” Empire, whose capital was Constantinople (modern Istanbul). [1] How did they get to Venice?

Venice and the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, approximate boundaries, late-12th century (underlying map © Google)

In 1204, Venetians were among the crusaders of the Fourth Crusade who sacked Constantinople and looted its great palaces and churches. The crusaders melted down many objects of precious metals that could be easily converted into money. But they also brought home objects and donated them to churches like San Marco. Such objects were likely preserved because of their precious materials, artistic beauty, and sacred functions, as well as the fact that many were made of materials like stone or glass that could not be melted down and converted into money. In their new settings, some objects continued to be used for their original functions, while other objects were repurposed for new uses. Such works illustrate how portable objects could move between cultures and be reused in the medieval world.

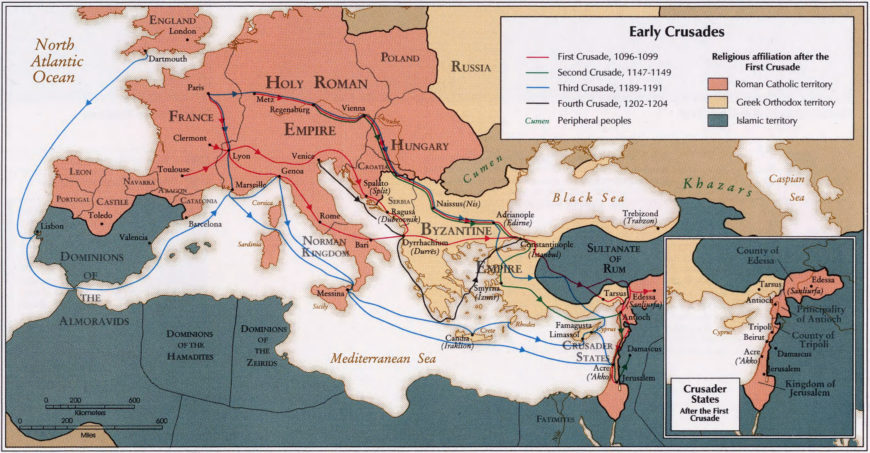

Map with the routes of the First through Fourth Crusades, from Atlas of the Middle East (Central Intelligence Agency, 1993)

Reusing ancient stone vessels

Perhaps surprisingly, some of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) objects in the treasury of San Marco were themselves products of reuse of even older objects from the ancient world. Consider the example of two tenth-century chalices—one with handles and one without—which bear inscriptions that refer to an Eastern Roman emperor named Romanos (either Romanos I Lekapenos, or Romanos II. The Romanos chalice with handles combines a sardonyx stone bowl with delicately carved handles and a silver gilt setting. It is decorated with precious stones and colorful cloisonné enamel icons of Christ, angels, and saints. An enamel inscription beneath the bowl of the chalice reads: “Lord help Romanos, the Orthodox ruler.”

Chalice of Emperor Romanos (with handles), Byzantine, 10th century (with antique sardonyx bowl), sardonyx, silver gilt, gold cloisonné enamel, stones, 25 cm high (photo © Regione del Veneto)

The Romanos chalice without handles similarly combines a sardonyx stone bowl with a silver gilt setting and is decorated with enamels and pearls. The same inscription referring to Romanos appears around the base of the chalice, telling us that this vessel must have been produced for the same emperor Romanos.

Chalice of Emperor Romanos (without handles), Byzantine, 10th century (with antique sardonyx bowl), sardonyx, silver gilt, gold cloisonné enamel, pearls, 22.5 cm high (photo © Regione del Veneto)

In Constantinople, these opulent objects were once used in the celebration of the Eucharist, in which bread and wine were offered to God, then consumed by worshippers as the body and blood of Christ. It is easy to imagine the worshippers’ awe as they approached these shining vessels, which mediated their encounter with Christ. Catching a glimpse of the inscriptions on these vessels, worshippers might have spoken the inscribed prayer on behalf of the emperor.

Greek inscription: “Lord help Romanos, the Orthodox ruler,” Chalice of Emperor Romanos (without handles) (photo © Regione del Veneto)

The stone bowls of both chalices were ornately carved by highly skilled artisans. Although they are difficult to date with precision, art historians believe that they were not fashioned in the tenth century when the chalices were made. More likely, they were produced in antiquity, centuries earlier. Although the stone bowls were not originally intended for Christian chalices, the emperor Romanos (I or II) likely commissioned artisans to transform these stone bowls into chalices because of their exquisite craftsmanship and because their red hues and swirling textures evoked the wine of the Eucharist, believed to be the blood of Christ.

Reusing Islamic glass

Another chalice in San Marco, also likely looted from Constantinople by the crusaders, incorporates a vivid green glass bowl of Islamic origin. Decorated with a stylized running hare motif, the bowl was cut with a rotating wheel, a lapidary technique commonly used for sculpting stones. As such, it was likely produced in Islamic lands: either in ninth- or tenth-century Iran, or perhaps tenth- or eleventh-century Egypt, where this technique was used. Eastern Roman artisans probably transformed the green glass bowl into a chalice in the eleventh century with the addition of a silver gilt setting, gems and pearls, and an enamel inscription. Now partially lost, the inscription once read, “Drink of this all of you, this is my blood of the new covenant, which is shed for you and for many for the remission of sins.” These words, spoken by Christ at the Last Supper and repeated by the clergy during the celebration of the Eucharist in the Eastern Roman Empire, enable art historians to identify this vessel as a Eucharistic chalice with confidence.

Chalice with hares, Byzantine, 11th century (?) (with glass bowl probably from 9th–10th century Iran or 10th–11th century Egypt), glass, silver gilt, enamel, stones, pearls (photo © Regione del Veneto)

But how did this Islamic bowl end up in the Eastern Roman Empire and why did the Eastern Romans transform it into a chalice for the Eucharist?

It is possible that the green glass bowl came to Constantinople the same way that it eventually traveled from Constantinople to Venice: as booty from war (though not a crusade). The Eastern Romans made military gains against their Islamic neighbors to the east during this period and may have taken this glass bowl as plunder from Islamic lands. On the other hand, war was not the only way that objects traveled between cultures in the medieval Mediterranean, and there is no evidence that this bowl was brought to Constantinople as war booty. Historical documents record that glass vessels like this one were sometimes among luxury objects exchanged as diplomatic gifts by Eastern Roman rulers and their Islamic neighbors, so it is possible the green glass bowl came to Constantinople as a diplomatic gift from the Abbasids, Fatimids, or some other people. It is also possible that the green glass bowl simply came to Constantinople through trade. The tenth-century Book of the Eparch (a book of Eastern Roman commercial law) testifies that there was a market for Islamic goods in Constantinople at this time. But since we lack explicit textual evidence to corroborate any of these theories, we cannot say for certain how the green glass bowl came to Constantinople.

Materiality and ornament

As with the Romanos chalices, the materiality of the green glass bowl was surely an important factor in this object’s reuse. The stunning green hue of the glass bowl is unusual among surviving Islamic glass work. Both its color and its fashioning with a wheel were likely intended to produce the appearance of a precious stone, such as an emerald. And as with other Eastern Roman glass chalices, the transparency of the green bowl would have enabled worshippers to glimpse the Eucharistic wine while the inscription around its rim affirmed that it was the very blood of Christ.

Chalice with hares, Byzantine, 11th century (?) (with glass bowl probably from 9th–10th century Iran or 10th–11th century Egypt), glass, silver gilt, enamel, stones, pearls (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The bowl’s running hare motif, however, is unique among surviving Eastern Roman chalices. Many Eastern Roman viewers would likely have recognized the angular hare motif as not Eastern Roman and perhaps even as Islamic in origin. This raises questions about why such a vessel might be converted into a chalice for the Eucharist, and how Eastern Roman users would have understood it.

Hare motif (highlighted), Chalice with hares, Byzantine, 11th century (?) (with glass bowl probably from 9th–10th century Iran or 10th–11th century Egypt), glass, silver gilt, enamel, stones, pearls (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Art, court, and diplomacy

To answer these questions, it is important to understand this vessel as a product of both the church and court of Constantinople. Although this chalice bears no donor inscription like those attributed to emperor Romanos, its costly materials and high quality of craftsmanship indicate that it too was likely commissioned by an emperor or some other elite patron in the court in Constantinople. As such, we can understand this vessel as one of many examples of Eastern Roman appropriation and imitation of Islamic culture in the tenth and mid-eleventh centuries. Such Islamic or Islamicizing elements appear on Eastern Roman clothing, jewelry, and lead seals of this period. Eastern Roman emperors and members of the court likely adopted such Islamicizing objects to project wealth, power, and a cosmopolitan identity.

Emperor Leo VI leads Arab diplomats into Hagia Sophia to show them church objects, in the Madrid Skylitzes, between 1126 and 1150? (Biblioteca Nacional de España, Vitro. 26-2, fol. 114v)

In addition to their primary ritual functions, there is also evidence that sacred objects like chalices sometimes played a role in Eastern Roman diplomacy. The eleventh-century Eastern Roman historian John Skylitzes describes how the emperor Leo VI led Arab diplomats into the church of Hagia Sophia and showed them sacred vessels and other church objects—an episode illustrated here in a twelfth-century copy of Skylitzes’s history. In this scene, two Arab figures enter the church from the left, while the emperor—crowned and clad in gold—points to a golden chalice and other church objects held for display by church officials.

Chalice with hares, Byzantine, 11th century (?) (with glass bowl probably from 9th–10th century Iran or 10th–11th century Egypt), glass, silver gilt, enamel, stones, pearls (photo:

byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

So, we can conclude that the patron of the chalice with hares likely intended Eastern Roman viewers (and perhaps even foreign visitors) to recognize the Islamic origin of the green glass bowl with hares. To display such a beautiful object of Islamic origin in tenth- and eleventh-century Constantinople was to project wealth, power, and a cosmopolitan identity. If there were any concerns about using an Islamic object for Christian religious purposes, the chalice’s Eastern Roman setting with its Christian inscription must have rendered the glass bowl suitable for use in the celebration of the Eucharist. An inventory of objects in the church of San Marco from 1325 mentions a “green chalice decorated with silver,” perhaps referring to the chalice with hares and suggesting that this object may have continued to function as a Eucharistic vessel even after it was transferred from Constantinople to Venice. Together with the Romanos chalices, the chalice with hares shows the important roles that materiality, ornament, and craftsmanship could play in an object’s cross-cultural mobility, reuse, and preservation through the centuries.