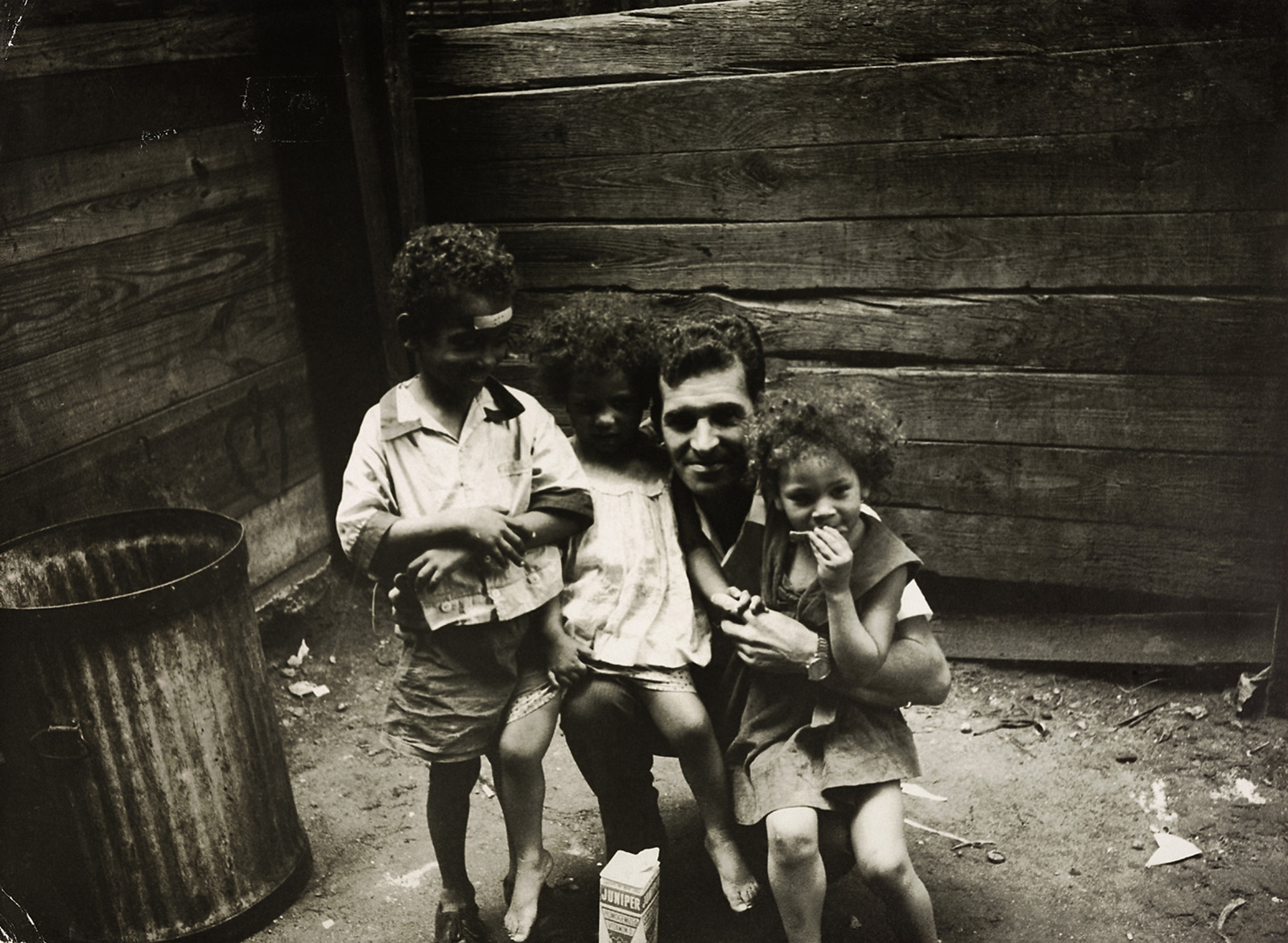

O fotógrafo Henri Ballot com Ely-Samuel, à esquerda, e seus irmãos (Photographer Henri Ballot with Ely-Samuel and his brothers), 1961, Henri Ballot. 6.9 x 9.3 in. Copyright Instituto Moreira Salles Collection

In late July 1961, O Cruzeiro magazine—Brazil’s answer to the American magazine Life—sent photographer Henri Ballot to document poverty in New York City. Ballot’s assignment had been issued in direct response to “Freedom’s Fearful Foe: Poverty,” a photo-essay Life had published the month before featuring reporting, diary entries, and photographs by Gordon Parks about the living conditions of young Flávio da Silva and his family in the favela of Catacumba in Rio de Janeiro.

O Cruzeiro had taken issue with the suggestion in the Life photo-essay, popularly known as “the Flávio Story,” that poverty was endemic to Brazil and to Rio, the country’s best-known city.

On October 7, 1961, O Cruzeiro published Ballot’s photographs and reporting as a page-by-page comparison with “Freedom’s Fearful Foe,” heralding the report on the issue’s cover with a headline just as sensationalist: “Nôvo recorde americano: Miséria” (New American Record: Poverty”). Two weeks later, the October 20, 1961 issue of Time (a sister publication to Life) included an article titled “Carioca’s Revenge,” which attacked the veracity of Ballot’s story. In November, O Cruzeiro responded by accusing Parks of staging his reportage.

The clash continued for months. Why? In order to better understand this battle between magazines, we can look at the motivations of O Cruzeiro, Ballot, and Life at the time. Taken together, they convey a story about photography as a significant form of representation, interpretation, and documentation, and about the often ambiguous role it plays in what sociologist Herbert J. Gans has called the “symbolic arena” of the international news media.

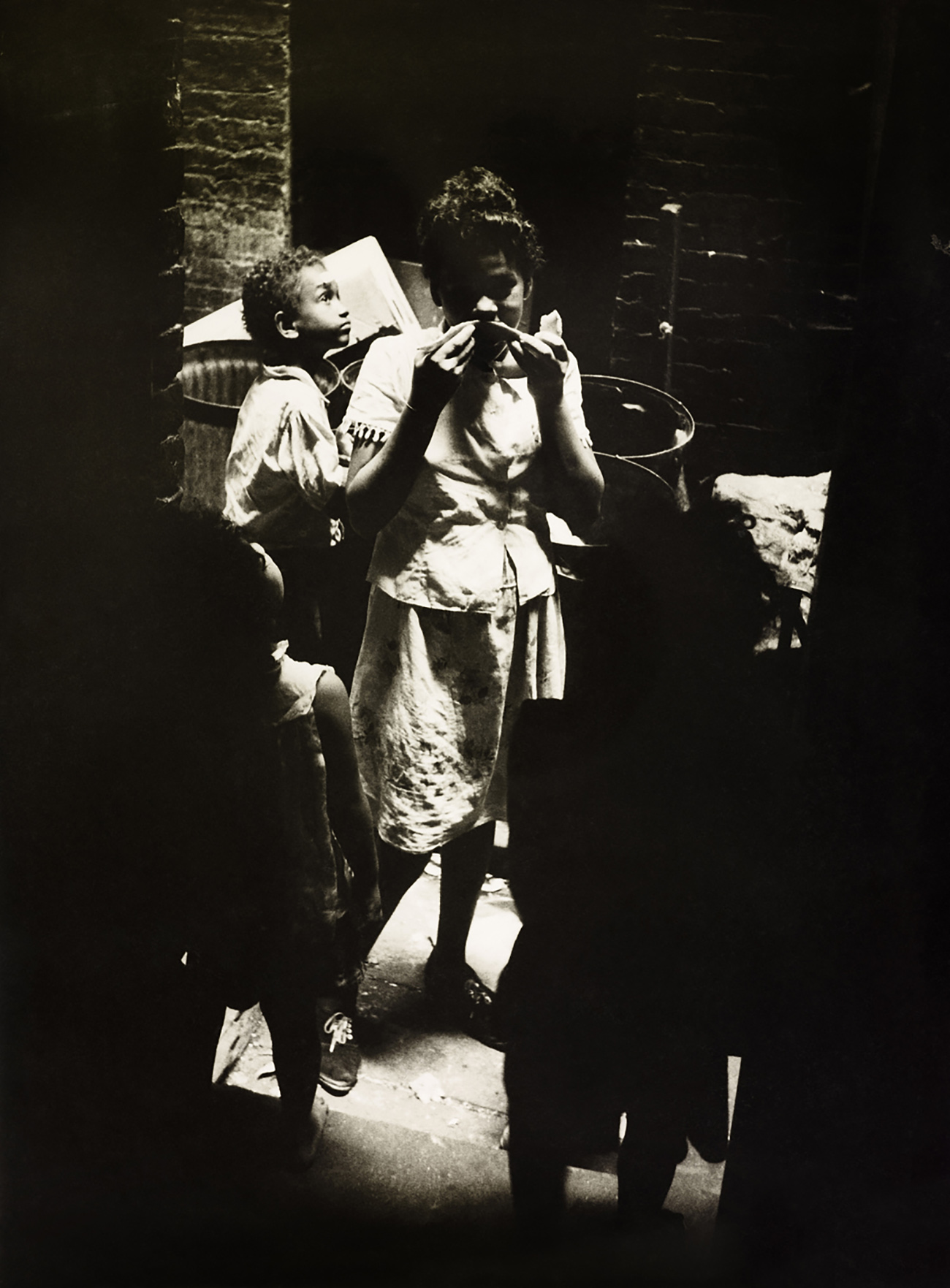

Edifício onde morava a família Gonzalez (The Building Where the Gonzalez Family Lived), 1961, Henri Ballot. Gelatin silver print, 7.1 x 9.5 in. Copyright Instituto Moreira Salles Collection

Origins and Evolution of O Cruzeiro

O Cruzeiro began as a standard illustrated magazine produced in Rio de Janeiro and distributed nationwide. It was part of the media group Diários Associados, which had been founded and led by the journalist Francisco de Assis Chateaubriand Bandeira de Mello, Brazil’s most powerful press baron in the 1930s. In the first period of its existence, from 1928 to 1940, it made extensive use of illustrations and photography in a wide range of articles and reports, with regular contributions from writers, poets, and visual artists.

In the early 1940s, O Cruzeiro underwent a change in its editorial policy, strengthening the link between journalism and photography. It contracted French photographer Jean Manzon, who had worked for both Paris Match and Vu, to reorganize the magazine’s photography department. From 1941, Manzon emphasized photojournalism, but in the service of providing spectacle and sensationalist commentary rather than factual, objective, and impartial reportage. Despite its tendency to stage content to fit its chosen themes—or perhaps precisely because of it—O Cruzeiro’s circulation grew in the 1940s, achieving a weekly readership of more than 700,000 in the mid-1950s.

Such growth encouraged the magazine to invest heavily in hiring new photographers and journalists. Between 1946 and 1951, when Jean Manzon left the magazine, many new photographers joined its staff, including Henri Ballot, Luiz Carlos Barreto, Luciano Carneiro, Flávio Damm, and José Medeiros. This new generation arrived just after the end of Getúlio Vargas’s strong and dictatorial regime (particularly the Estado Novo period of 1937 to 1945), and following the country’s first free elections, which initiated nearly 20 years of democracy.

Working together with a new crop of reporters and graphic artists, they contributed to a significant change in direction for O Cruzeiro, producing a more engaged and humanist style of journalism and photojournalism.

The new photographers were inspired and influenced by the international photography and journalism of the 1940s and 1950s, which included famous photo-essays in Life by photographers such as W. Eugene Smith, the work of French photographers such as Robert Doisneau and Willy Ronis, as well as events like the establishment of the Magnum Photos agency in 1947.

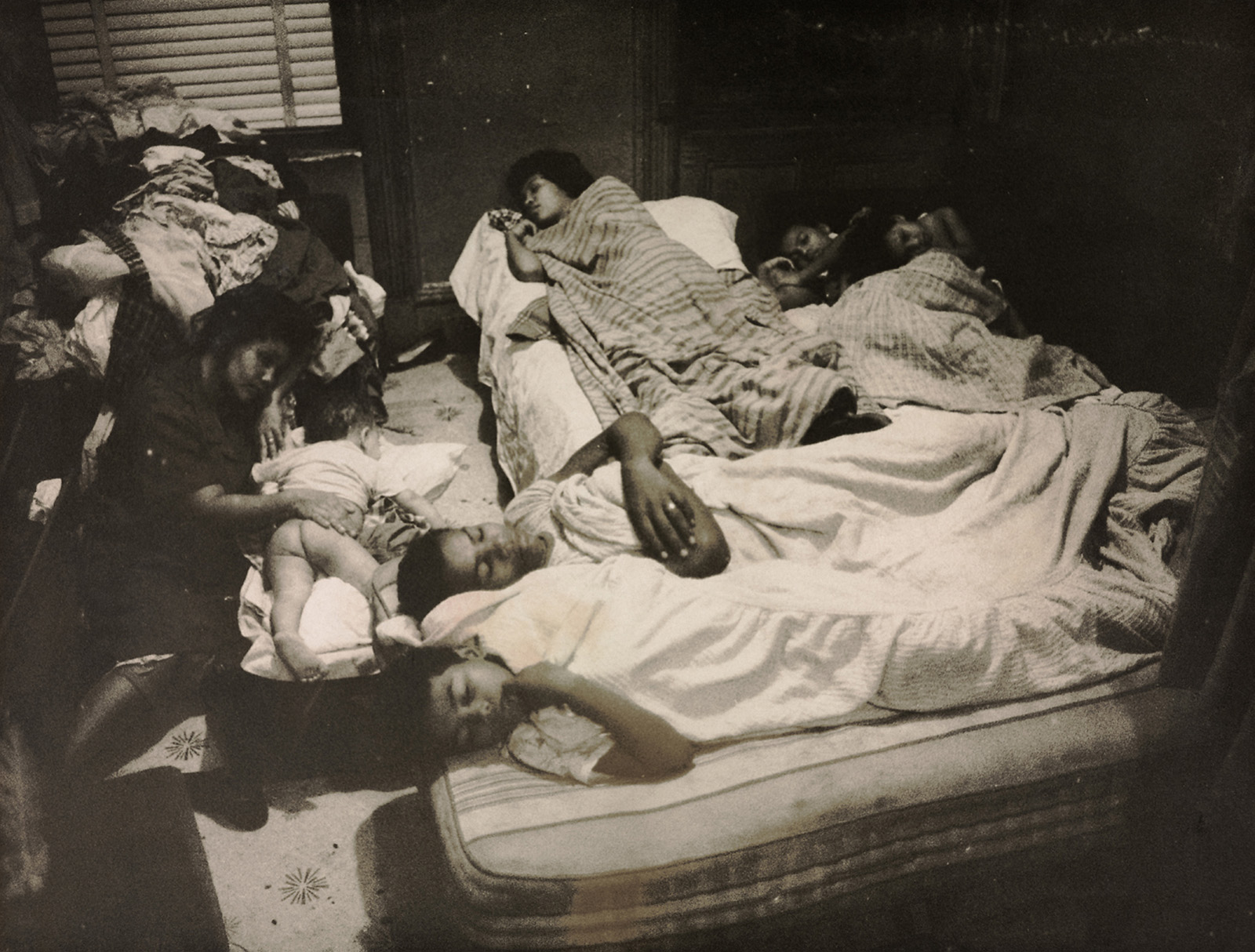

Quarto na casa da família Gonzalez (Room at Gonzalez Family House), 1961, Henri Ballot. Gelatin silver print, 7.2 x 9.5 in. Copyright Instituto Moreira Salles Collection

Photographer Henri Ballot and His Side of the Flávio Story

Photographer Henri Ballot joined the staff of O Cruzeiro in the early 1950s. The son of a Brazilian woman and a French engineer and aviator, he was born in Pelotas, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. When he was two years old, his parents moved the family to France. By the time he was 17, Ballot was already—like his father—a trained pilot, one of the first to work for Aéropostale, the French airmail service and predecessor of Air France (alongside well-known author Antoine de Saint-Exupéry).

At the beginning of World War II, Ballot was imprisoned by German armed forces in Spain for four months for removing French airplanes from the path of the invading army. After he was released, he became a pilot in the Free French Air Force in England. He had a serious crash at the end of the war, when his aircraft was hit by German anti-aircraft fire, and landed in an area controlled by American troops.

Taken to a hospital in Colorado in the United States, Ballot was in a coma for months after the crash. After regaining consciousness, and during his long recovery, he learned photography in the hospital alongside other patients. Ballot returned to France, but in 1949 decided to relocate to Brazil. Soon after arriving, he secured work as a photographer for O Cruzeiro based at the magazine’s São Paulo office.

Between 1949 and 1968, Ballot produced many historically significant documentary photo-essays. For instance, between 1952 and 1957 he accompanied the brothers Villas-Bôas on their pioneering Roncador-Xingu expeditions to the rainforest-rich state of Mato Grosso, recording some of their first moments of contact with the indigenous peoples of the Xingu. He also documented the negotiations that culminated in 1961 in the creation of the Xingu National Park (today the Xingu Indigenous Park).

Among the other subjects Ballot covered as a photojournalist were migrants from the northeast of Brazil to São Paulo (retirantes), the coastal peoples of the Southeast (caiçaras), the samba schools and favelas of Rio de Janeiro, and the building of the Transamazônica highway. Ballot’s archive of more than 13,000 photographs is now part of the collection of Instituto Moreira Salles.

Criança brincando em meio ao lixo (Child Playing in the Trash), 1961, Henri Ballot. Gelatin silver print, 7.1 x 9.5 in. Copyright Instituto Moreira Salles Collection

Ballot Takes on Poverty in the United States

For his assignment in New York in 1961, Ballot conducted research and consulted with various organizations and associations that supported the city’s underprivileged Hispanic communities. The photographer walked through areas of Harlem and the Lower East Side, depicting the neighborhoods and families living there.

His early explorations of New York focused on impoverished and marginalized residents found on East 100th Street, whom American photographer Bruce Davidson would also later feature in his famous series bearing the name of that street. Despite some false starts that yielded little, Ballot was determined to make an objective and impartial record of the social inequalities that existed in the United States.

After more than 20 days of walking the streets of New York in search of a potential subject, he chose to interview and photograph the Gonzalez family: parents Félix and Esther and their six children, including nine-year-old Ely-Samuel. Originally from Puerto Rico, they lived in a small tenement apartment on Rivington Street in the Bowery, on the Lower East Side of Manhattan—not far from Wall Street, the financial heart of the US.

Crianças brincando no pátio interno do edifício (Kids Playing in the Courtyard of a Building), 1961, Henri Ballot. Gelatin silver print, 9.5 x 7 in. Copyright Instituto Moreira Salles Collection

Ballot recorded his first walks, daily impressions of the city, and his encounters with the Gonzalez family in a revealing diary. This artifact, along with correspondence, news clippings, and a unique set of approximately 150 vintage photographs, provides a comprehensive report of his stay in New York and is preserved in his archive at Instituto Moreira Salles.

Also included among his photographs is an additional project that appears to have been triggered by the publication of “Carioca’s Revenge.” Several images document visits Ballot paid to the da Silva family in Brazil during the early fall, after he returned from New York. These were complemented by interviews with José da Silva and some of his children, both in their new home (purchased with donations from Life’s readers), as well as in their former Catacumba shack and the kerosene stall that José managed.

These images were ultimately published just one month later, in the November 18, 1961 issue of O Cruzeiro, and illustrate the magazine’s efforts to uncover fabrication and manipulation in Parks’s original coverage of Flávio and his family.

A Battle in Print—with Real Consequences

The dispute that developed between O Cruzeiro and Life resulted in mutual disparagement of both Parks’s and Ballot’s original stories. It also marked the future paths of the photographers. Both faced monumental challenges as they sought to defend and maintain the integrity of their original narratives while their respective publications waged a larger ideological war.

Parks and Ballot produced photographs under the auspices of photojournalism. The dossier Ballot put together on his reportage in New York is fortunately preserved in his archive. An analysis of his photographs, diary, and other documents does not reveal any intended desire to alter the facts. Rather, his work echoes contemporary exemplars such as Davidson, Helen Levitt, and members of the Photo League, who made detailed documentations of street life and social issues in New York City following World War II.

Editors at O Cruzeiro chose to publish Ballot’s images in a layout that directly corresponded to how Life’s editors had sequenced and edited Parks’s photo-essay. The unabashed comparison suggests that O Cruzeiro’s editors felt it necessary to issue an unequivocal response to “Freedom’s Fearful Foe,” which would reinforce how poverty could be found in the largest city in the United States, just as it existed in Rio de Janeiro.

In retrospect, this was a questionable editorial decision. The layout in O Cruzeiro invited accusations that Ballot’s reportage was manipulated, in part because it seemed visually weaker and less powerful than Parks’s, but primarily because it was clearly rhetorical and propagandistic. By failing to present Ballot’s work as independent and critical, the editors inadvertently exposed the Brazilian photographer—and the magazine itself—to criticism. This made it easy to ignore the content itself.

Família Gonzalez (Gonzalez Family), 1961, Henri Ballot. Gelatin silver print, 6.6 x 9.5 in. Copyright Instituto Moreira Salles Collection

Despite Ballot’s and Parks’s respective efforts to report on the unassailable fact that both the Gonzalez family and the da Silva family struggled to survive below the poverty line, Ballot and Parks were effectively trapped in an editorial duel that exemplified how communication can be easily transformed into propaganda in the symbolic arena of the press. The two major illustrated magazines operated in a specific geopolitical context and moment, marked by the Kennedy administration’s first moves following the recent Cuban Revolution and its reverberations throughout the world, specifically in Latin America. At the very same time, Life and O Cruzeiro were also competing for domination of the Latin American news market by distributing their respective Spanish-language editions throughout the region.

In this context, the original intention of many photojournalists who worked for these magazines, including Parks and Ballot, to communicate facts directly and objectively was often lost; instead, their content was edited and published with a strong symbolic and ideological slant.

The episode reveals how such approaches by the press can override and contaminate the subjects portrayed. It also had two important consequences for Ballot: he was forced to live with Time’s accusation—which he emphatically denied—that he had modified images in his report, especially a shocking image of Ely-Samuel Gonzalez in bed as cockroaches crawled over his body, and was also refused entry to the US after O Cruzeiro published the report.

Today, photographic images continue to be powerful, particularly given corporate journalism networks and social media. They contend with many of the same issues evident in the confrontation between Life and O Cruzeiro: questions of authorship, documentation, editing, ethics, staging, ideology, and propaganda.

To understand the role of photography, now and then, we must be capable of critically discerning how every photographic image is presented to us. This is still a significant challenge, especially in a world struggling with the increasing pervasiveness of “fake news.”

Vista dos edifícios de Wall Street (View of Wall Street Buildings), 1961, Henri Ballot. Gelatin silver print, 9.5 x 7.1in. Copyright Instituto Moreira Salles Collection

This essay originally appeared in the iris (CC BY 4.0)