Modern China (1912–present): an introduction

Read Now >Chapter 70

The potentials of modern Chinese art in the Republic of China (1912–49)

Introduction: Art and Modern China

Hu Yichuan, To the Front!, 1932, woodcut, 1932, 9 1/8 x 12 inches (Lu Xun Memorial, Shanghai)

After uprisings and civil disorder in the nineteenth and early twentieth century, a revolutionary army founded the Republic of China (ROC) and overthrew the Manchu-ruled Qing dynasty in 1912. The short but critical period that lasted from 1912 to 1949 is commonly recognized as the beginning of China’s modern era, during which the country transitioned from an imperial system (ruled by hereditary emperors) to a Republican government established by Sun Yat-sen of the Nationalist Party (KMT or GMD, Guomindang 國民黨). While the Nationalists struggled to establish a new government amid Japanese aggression, civil war, and the outbreak of World War II, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP, or Gongchandang 共产党) formed in Shanghai and gradually gained power.

Amid this tumultuous moment, many artists questioned the role of Chinese culture, education, and the arts and their direction in the modern era. This chapter highlights artists’ impulses to probe and define the potentials of modern Chinese art, including their efforts to reform or revive traditional Chinese painting in light of broadened exposure to Western art, and by developing new media altogether.

The New Culture Movement

Artists initially responded to the rapidly changing politics and ideologies of the Republican era by seeking out a wide range of experiences. Many artists studied abroad in Japan and Europe, where they embraced practices such as drawing from a live model, which they observed in the studios (“ateliers”) of their European contemporaries. Gradually, private studios modeled after the Paris atelier began to appear in Shanghai. New painting societies formed to advance new theoretical concerns through journals and art exhibitions. Meanwhile, the Minister of Education, Cai Yuanpei, promoted the belief that aesthetic education supported social stability, which became a guiding principle in the creation of China’s first art schools. These schools looked to the curriculum of the international art schools of Japan and Europe, rather than to imperial workshops of the previous era. These progressive ideals shaped what is called the New Culture Movement (xin wenhua yundong 新文化運動) of the 1910s and 1920s, inspiring artists to explore the synthesis of Western and Chinese practices and generating new possibilities for Chinese art.

Cai Yuanpei, “On New Education"

When you feel related to actual phenomena neither by craving nor by loathing, but are purely absorbed in artistic appreciation, then you will become a friend of the Creator and will be close to the conception of the world of reality. Therefore, if an educator wishes to lead the people from the phenomenal world to the conception of the world of reality, he must adopt aesthetic education.

美感者。含美麗與尊嚴而言之。介乎現象世界與實體世界之間。而爲之津梁。此爲康德所創道。而嗣後哲學家未有反對之者也。在現象世界。凡人皆有愛惡驚懼喜怒悲樂之情。隨離合生死禍福利害之現象而流轉。至美術。則卽以此等現象爲資料。而能使對之者自美感以外。一無雜念。例如采蓮煑豆。飮食之事也。而一入詩歌。則別成興趣。火山赤舌。大風破舟。可駭可怖之景也。而一入圖畫。則轉堪展玩。是則對於現象世界。無厭棄而亦無執著也。人旣脫離一切現象界相對之感情。而爲渾然之美感。則卽所謂與造物爲友。而已接觸於實體世界之觀念矣。故敎育家欲由現象世界而引以到達於實體世界之觀念。不可不用美感之敎育。

in Jiaoyu zazhi 教育雜誌 (Journal of Education) 3, no. 11 (1912). Translation from Mayching Kao, “Reforms in Education and the Beginning of the Western-Style Painting Movement in China,” in Century in Crisis, p. 153.

The movement began when the revolutionary Chen Duxiu—who Cai later invited to be dean at Peking University—wrote a seminal article in the journal New Youth, urging cultural progress through democracy and science. Rallied by Chen’s call, artists also felt inspired to explore the synthesis of Western and Chinese practices and generate new possibilities for Chinese art.

Chen Duxiu, “A Letter to Youth” (Jinggao qingnian 敬告青年)

Youth is like the early spring, like the rising sun, like a hundred flowers sprouting, like a blade fresh off the whetstone, the most precious time in life. Youth is to society, just as fresh and vigorous cells are to the human body, as in metabolism, wherein that which is stale and decayed is always on the way to being naturally eliminated, while that which is fresh and vigorous is positioned for life in its place. If the human body follows the way of metabolism, it is healthy, but if the stale and decayed cells fill the body, it will die. Society flourishes when it follows the way of the metabolism, and society perishes when filled with stale and decayed elements.

青年如初春,如朝日,如百卉之萌動,如利刃之新發於硎,人生最可寶貴之時期也。青年之於社會,猶新鮮活潑細胞之在人身,新陳代謝,陳腐朽敗者無時不在天然淘汰之途,與新鮮活潑者以空間之位置及時間之生命。人身遵新陳代謝之道則健康,陳腐朽敗之細胞充塞人身則人身死;社會遵新陳代謝之道則隆盛,陳腐朽敗之分子充塞社會則社會亡。

in Xin qingnian 新青年 (New Youth) 1, no.1 (1915). Translation by Kristen Loring Brennan.

Tiananmen Square on 4 May 1919. Around 3,000 students from 13 universities in Beijing gathered there to oppose Article 156 of the Treaty of Versailles. This officially sparked the May Fourth Movement (Hong Kong Central Library)

Several transformative events mobilized artists during the early years of the Republican era, fueled by the New Culture Movement. Significantly, the patriotic May Fourth Movement of 1919 drew attention to anti-imperialist sentiments among Chinese but also demonstrated the power of the masses overall. Japanese aggression led to the Second Sino-Japanese War, notably followed by the Nanjing Massacre of 1937 during which the Imperial Japanese Army horrifically murdered Chinese civilians. Public outcry over these humiliating events prompted many debates on the direction of China, propelling the rise of the Chinese Communist Party and demonstrating the role of art in galvanizing the Chinese public—as this chapter demonstrates.

Read an essay for more historical background

/1 Completed

Reforming Chinese art

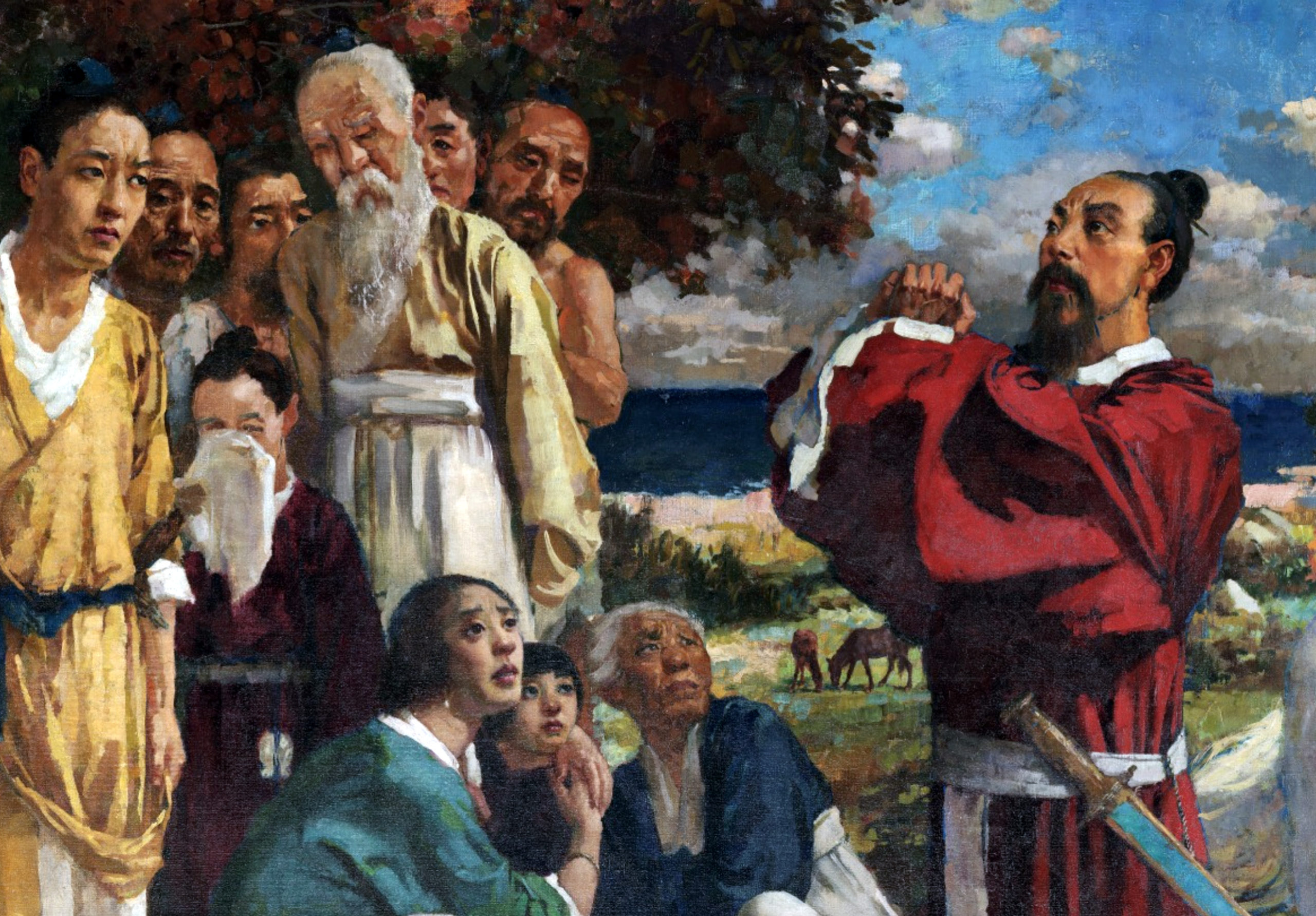

Xu Beihong, Tian Heng and His Five Hundred Followers, 1928–30, oil on canvas, 197 x 349 cm (CAA Art Museum, Beijing)

Moved by the patriotic sentiments of the moment, Chinese intellectuals—many of whom studied in Japan or Europe—were intent on reforming China to build a modern nation-state. While some artists defended what is traditionally referred to as “literati painting” (a self-expressive, conceptual, and often abstract mode of ink painting), others looked to European oil painting as the future of modern art in China. Even then, artists took wildly divergent paths—for instance, some emphasized the realistic techniques of European academic art, while others engaged with the more abstract approaches of European modernists.

The artist Xu Beihong, for instance, advocated a complete reform of Chinese painting to incorporate realistic observation of contemporary life and techniques found in Western painting. He went to both Japan and Europe and studied oil painting in the academic Salon style He then returned to China, where he painted in both non-traditional oil and in traditional ink. Teaching in Beijing, he sought out other European-trained artists such as the woman oil painter, Pan Yuliang, as well as ink painters who worked in both syncretic (assimilating Western techniques) and Chinese modes. His theories, in addition to the patriotic themes of works including the history painting, Tian Heng and His Five Hundred Followers, aligned with Cai Yuanpei’s views on aesthetic education as a path to salvation of the nation.

Demonstrating central objectives of the New Culture Movement, Xu argued in his writings for the strengths of realistic painting in Europe (and against the modernist works of contemporaries like Picasso), in hopes that Chinese painters would bring these practices into their own work.

Xu Beihong

To reform Chinese painting, artists must “preserve those traditional methods which are good, revive those which are moribund, change those which are bad, strengthen those which are weak, and amalgamate those elements of Western painting which can be adopted.”

Translation in Sullivan, p. 69.

Lin Fengmian, Seated Woman, late 1970s, ink and color on paper (hanging scroll), China, 68.6 x 65.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

One notable contemporary, Lin Fengmian, looked instead to modern European artists including Matisse, Van Gogh, and Cézanne. He similarly had returned to China after a stint in Europe, whereupon Cai Yuanpei invited him to lead a national art school in Hangzhou. Though few of Lin’s paintings survived, his modernist works offered a new direction for ink painting. (or “New Art”) shared by many, including Liu Haisu, who founded the first academy of art in Shanghai—a center for modernist trends in Western and Chinese painting.

Lin Fengmian, manifesto at the Great Beijing Art Meeting 北京藝術大會, 1917

Down with the tradition of copying!

Down with the art of the aristocratic minority!

Down with the antisocial art that is divorced from the masses!

Up with the creative art that represents the times!

Up with the art that can be shared by all the people!

Up with the people’s art that stands at the crossroads!

Translation in Sullivan, p. 44.

These artists, among many others, highlight the political and institutional aspects underlying art in Republican China: they typically studied European art abroad, created a repertoire of works in both oil and ink, directed China’s first art schools, circulated their writings in journals, and taught a new generation of students—and offered entirely new approaches to painting.

Read essays about reforming Chinese art

Xu Beihong, Tian Heng and His Five Hundred Followers: Xu’s carefully composed work underscore his patriotic interests and desire to reform Chinese painting in the modern era.

Read Now >/1 Completed

Reviving guohua, or new national painting

Gao Jianfu, Lingnan School, Flying in the Rain, 1932, ink and color on paper (hanging scroll), China, 46 x 35.5 cm (Hong Kong, Art Gallery, Chinese University of Hong Kong)

Throughout the 1930s, the field of Chinese painting thrived with the broadening of theoretical concerns and emphasis on the arts for cultural progress. Even as the reform of Chinese art became part of the young republic’s agenda, many Chinese painters continued to work in the traditional ink painting mode and were active in “schools” or certain regions with loosely associated artistic networks or stylistic traits. These artists, including those from the Lingnan (a Cantonese region in Guangdong province) and Shanghai schools, often aimed to popularize art as a national language. They sought to revive the tradition of guohua 國畫, or national painting. This “new guohua” did not attempt to borrow heavily from what is called Occidental or Western-style painting (xiyanghua 西洋畫, typically oil on canvas). Rather, artists creating new national paintings sought to advance traditional Chinese ink painting from within its familiar medium of water-based ink on paper.

Gao Qifeng, Monkeys and a Snowy Pine, 1916, ink and color on paper (hanging scroll) (Hong Kong Museum of Art, Provisional Urban Council)

Artists of the Lingnan school launched a modern movement led by the artist Gao Jianfu and his brother Gao Qifeng in the southern province of Guangdong. Gao Jianfu had gone abroad to study in Japan, where he was inspired by the Japanese movement to revive their traditional painting, or nihonga 日本画, by introducing Western techniques such as shading, molding, and contemporary subject matter. His works typically adapted the medium of ink painting to modern themes by including subject matter, such as tanks and airplanes, or incorporated foreign techniques in portraying Chinese landscapes.

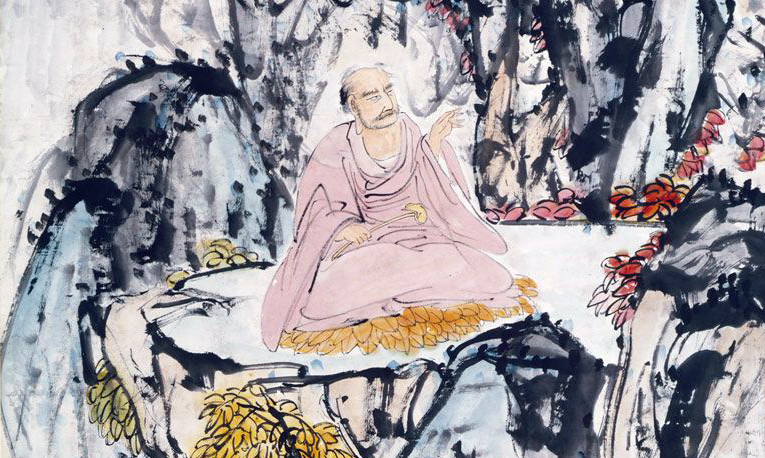

Wang Zhen, Buddhist Sage, dated October 20 1928, hanging scroll, ink and color on paper, 199.4 x 93.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

While not all artists studied abroad or sought to synthesize Western approaches, they nonetheless benefited from renewed interest in the arts and new avenues of patronage. Artists active in Shanghai during this period, known as the Shanghai school, catered to their urban clientele with ink painting subjects popular in the region, such as garden subjects and legendary figures that captured popular imaginations. As a dominant center for painting since the nineteenth century, artists in Shanghai were extraordinarily consequential for the direction of art schools and institutions, as well as the art market. For example, the artist Wang Zhen (also known as Wang Yiting) created ink paintings that appealed to both Chinese intellectuals and Japanese businessmen in Shanghai during the Republican era. With works marked by a sincerity of purpose and simplicity in brushwork, such as his depictions of Buddhist subjects, Wang participated in numerous charitable organizations that expressed the progressive ideals of his time.

Qi Baishi, Shrimps, 1927, ink on paper (hanging scroll), China, 97.5 x 47.6 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Circumventing the sophisticated tastes of his contemporaries, the Beijing-based guohua artist, Qi Baishi, rose to international renown through his expressive portrayals of simple subjects. Qi brought a lifetime of close observation of nature, such as plants, insects, and waterfowl, to render his subjects with spontaneity and compassion.

Read more about the Lingnan and Shanghai Schools

Wang Zhen, Buddhist Sage: How modern is this Chinese painting? Of course, it’s a trick question; it all depends on what you mean by “Chinese,” or by “modern.”

Read Now >

Gao Jianfu, Flying in the Rain: Motivated by a deep sense of patriotism, Gao offered a bold approach to the synthesis of Chinese and European traditions at a time when many questioned the future of the ancient tradition of Chinese ink painting.

Read Now >/2 Completed

Landscape painting and photography

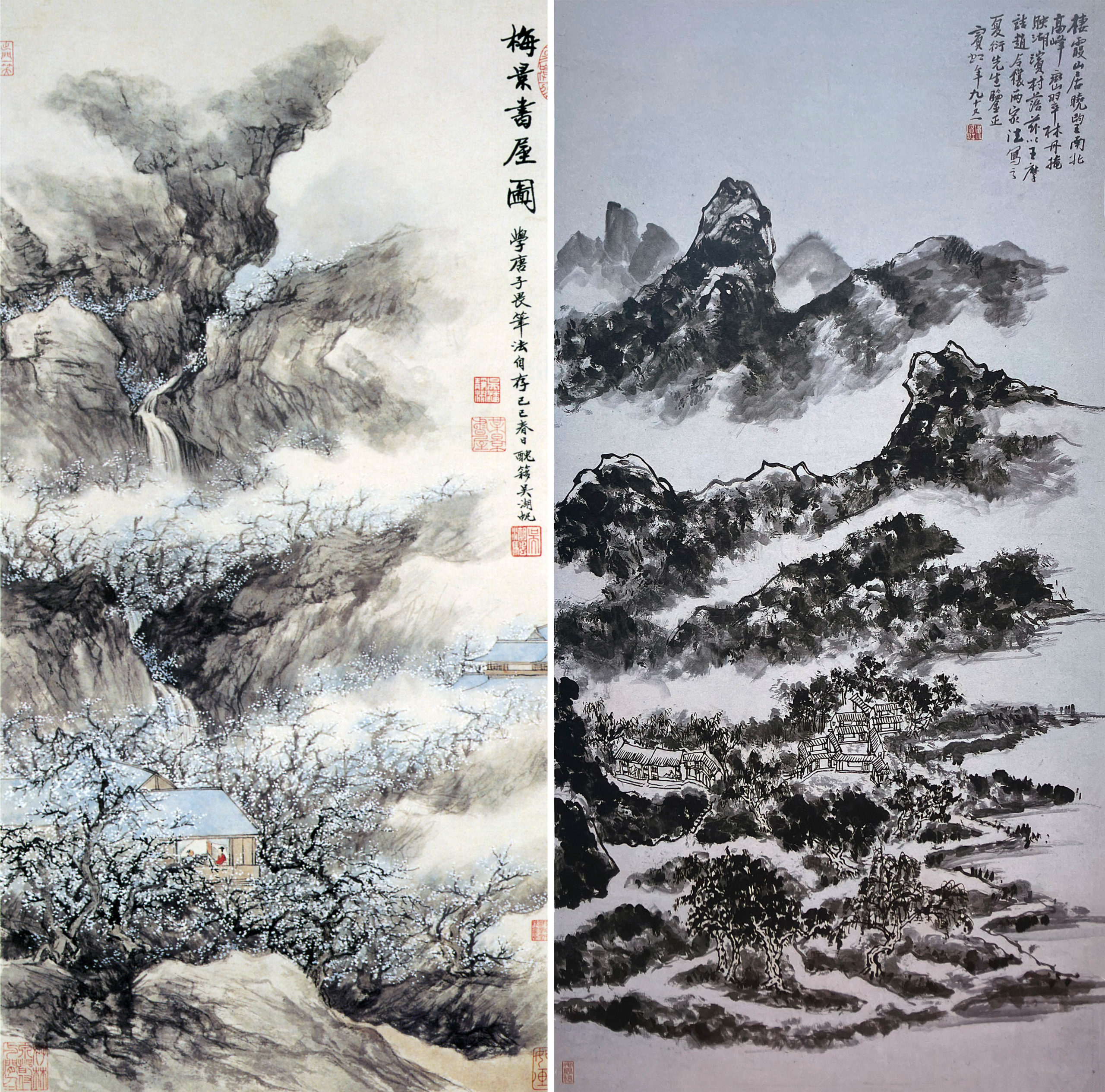

Left: Wu Hufan, Meiying Studio, 1929, ink on paper (hanging scroll) (Shanghai Museum, China); right: Huang Binhong, Dwelling in the Xixia Mountains, 1954, ink on paper (hanging scroll), China, 120.7 × 60.3 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Landscapes, having fallen from favor among urban patrons in cities like Shanghai during the late nineteenth century, enjoyed a revival among painting societies and in the curriculum of the new art schools in the 1930s. Artists such as Huang Binhong, Liu Haisu, He Tianjian, Feng Chaoren, Wu Hufan, Fu Baoshi, and many others viewed landscapes both as a foundation for China’s artistic tradition and as a central genre of national painting (guohua). Landscapes held a certain prestige as a favored subject of the literati, who wielded their brushes to relate to their environment and exercise their philosophical or aesthetic concerns.

Chen Hengke, Studio by the Water, dated 1921, ink and color on paper (album leaf), China, 33.7 x 47.6 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Notably, the artist and educator Chen Hengke defended the concept of “literati painting” (wenrenhua 文人畫), not with the intention of returning to landscape styles of imperial times, but rather to emphasize its modern, self-expressive impulses—giving rise to the modern practice of Chinese art history.

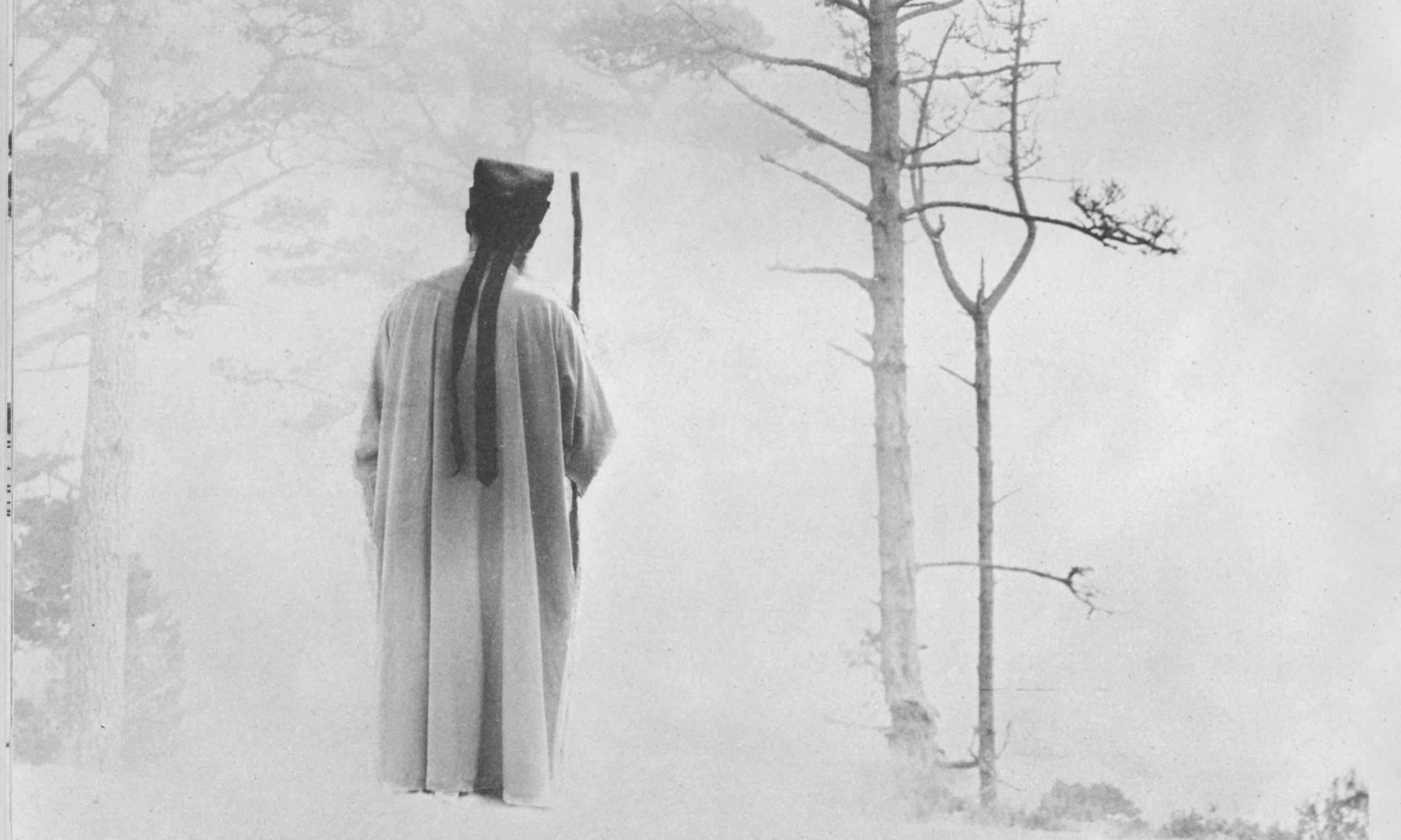

Looking to elevate landscapes as a patriotic symbol, artists also experimented with new techniques. The artist Lang Jingshan developed “composite photography,” which allowed for the assemblage of various photographic fragments into a single, unified composition. His use of familiar iconography and atmospheric features, such as mists and cloud banks, rendered the images as unmistakably modern Chinese landscapes—an inspiration to painters including the prolific artist, Zhang Daqian.

Read an essay about landscape painting and photography

Lang Jingshan and early Chinese photography: Can a photograph be appreciated in the manner of a Chinese painting?

Read Now >/1 Completed

The Modern Woodcut Movement

Li Hua, Roar, China, 1938, woodblock print, 27.5 x 18.7 cm (CAFA Art Museum, Beijing)

Art and activism intersected in China’s modern woodcut movement. The Modern Woodcut movement began in 1931 when the early Communist writer, Lu Xun, brought together a group of avant-garde artists (mostly young, modernist oil painters) for a workshop on Japanese printmaking. Angered by Japanese aggression and frustrated by political inaction, these early Communist artists such as Hu Yichuan and Li Hua looked to the black-and-white images of woodcut prints as a medium that could amplify their cause—to strengthen China and fend off imperialism.

Manifesto of the Spring Earth Painting Research Center 春地美術研究所, Shanghai, 1932

Modern art must follow a new road, must serve a new society, must become a powerful tool for educating the masses, informing the masses, and organizing the masses. This new art must accept this mission as it moves forward!

現代的美術必然要走新的道路,為新的社會服務,成為教育大眾,宣傳大眾與組織大眾的有力工具。新艺术必须负起这样的使命向前迈进!

Translation in Julia F. Andrews and Kuiyi She, “The Modern Woodcut Movement,” in A Century in Crisis, p. 216.

(To the Front! was exhibited at this 1932 exhibition at the YMCA in Shanghai)

Ming banknote, 1375, Ming Dynasty, China, paper, 34 x 21.8 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Woodcuts are images carved in relief (raised up) on blocks of wood, upon which paint is applied and then paper is smoothed on top to capture the impression—in other words, they are stamps. Unlike earlier woodblock prints that were invented in China, modern woodcut artists used oil-based paint rather than water-based ink, thereby aligning with European preferences. Rather than hire skilled artisans to carve the blocks, as in the Japanese printmaking tradition, artists of the modern woodcut movement carved their own reusable wooden blocks, thereby producing their prints from start to finish. Circulating their works among fellow Communists in exhibitions and print publications, these artists eschewed the mechanization and technological impulses of their modern moment to literally carve out a raw, visceral call to arms.

Read essay about the Modern Woodcut Movement

Hu Yichuan, To the Front!: This woodblock print represents one of many images widely circulated in efforts to foment resistance to the Japanese invaders and to denounce the inaction of those in power.

Read Now >/1 Completed

Art and War

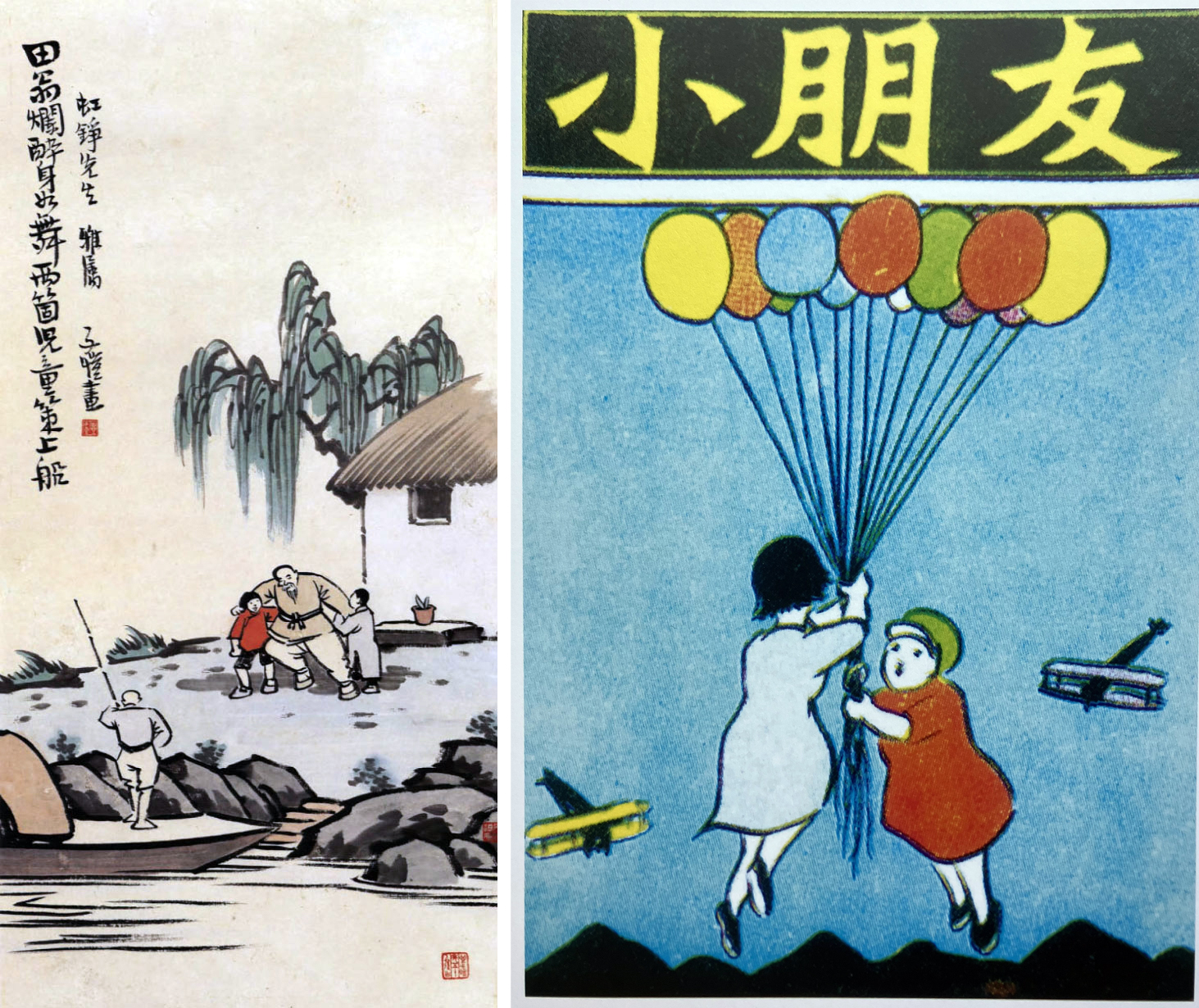

Left: Feng Zikai, Drunken Old Farmer, c. 1947, hanging scroll, ink on paper, China, 65.7 x 32.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art); right: Feng Zikai, Young Friends, September 1931, magazine cover

China descended into war with Japan in 1937, marking the start of World War II in Asia. At that time, the Nationalist government held only a portion of western China, while the Chinese Communist Party gained territory in the north and the Japanese occupied territories under a puppet regime. With their nation and culture under threat, artists faced difficult decisions—some went into exile, while others remained in occupied territories. Despite three years of civil war amid an eight-year war with Japan, many continued to make art. Printmakers continued to produce woodcuts with anti-Japanese themes and social concerns such as the suffering of the people. Others, such as the artist Feng Zikai who had studied in Japan, brought levity to the moment with paintings and cartoon-like prints (manhua 漫畫) inspired by Japanese woodblock prints and graphic novels (manga 漫画), laden with social commentaries and Buddhist themes. In contrast to the themes of war and human suffering in works by his contemporaries, Feng’s works such as Drunken Farmer offered playful social commentaries and Buddhist themes such as kindness and compassion.

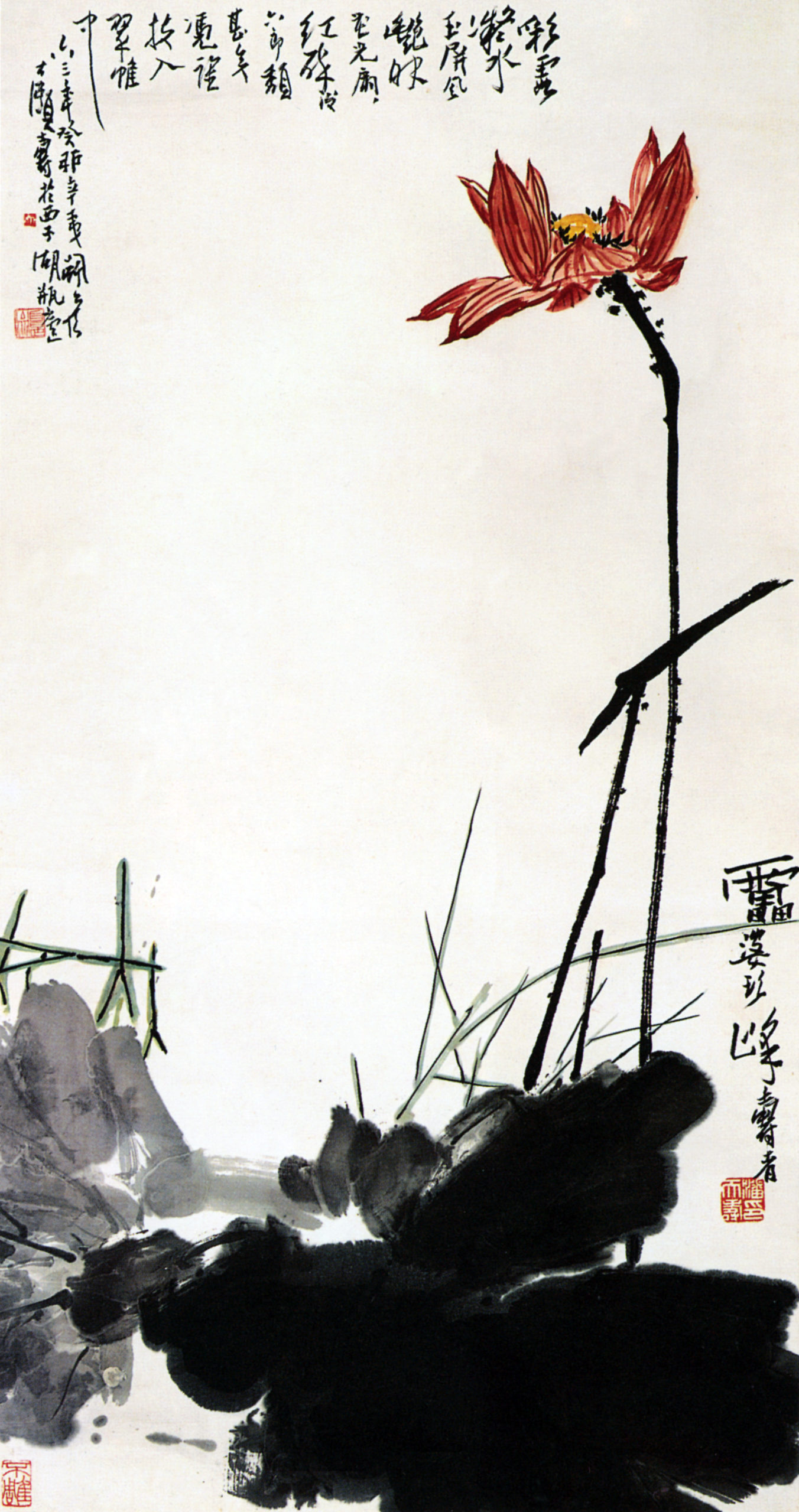

Pan Tianshou, Red Lotus, 1963, hanging scroll, ink and color on paper (Pan Tianshou Memorial, Hangzhou, China)

A prominent figure in the revival of guohua (national painting), as seen in Red Lotus, Pan Tianshou also developed an abstract, large-scale, horizontal compositional approach that embraced modernist sensibilities yet at times also used finger painting techniques of traditional Chinese painting.

Jiang Zhaohe, Refugees, 1943, ink and color on paper, 200 x 1202 cm (National Art Museum of China, Beijing)

Yet perhaps most emblematic is a realistic, life-size portrayal of refugees in guohua by Xu Beihong’s pupil, Jiang Zhaohe. Originally spanning twenty-six meters, this work details the tragic fate of China’s wartime refugees through close observation: over one hundred of the dead and dying (many of them women and children), based on real individuals hired by the artist as models.

Jiang Zhaohe, Refugees (detail), 1943, ink and color on paper, 200 x 1202 cm (National Art Museum of China, Beijing)

Though badly damaged and incomplete today, Jiang’s painting unveils the timeless horrors of war and human suffering.

Wrestling with China's cultural heritage

From the end of imperial rule to the rise of the Chinese Communist Party, artists of Republican China wrestled with China’s cultural heritage and direction in the modern era. Whether they demonstrated patriotism in new guohua or modernist oil paintings, or revolutionary fervor in woodcuts, they took an active, modern stance by reforming, adapting, and advancing a variety of art forms. Faced with Japanese aggression and domestic turmoil, artists organized numerous art schools, journals, exhibitions, art societies, and cultural exchanges—much of which directly benefited the war effort. After the Japanese surrendered to the Allies in 1945, the Communists expanded into areas held by the Japanese, and within three years won the civil war that ensued. The extraordinary uncertainty of this period challenged the ideals of many artists, just as it emboldened Communist attention to the importance of art for the masses.

Key questions to guide your reading

How did artists respond to the New Culture Movement?

What is guohua, or new national painting?

How did modern Chinese woodcuts differ from earlier paintings and prints?

Jump down to Terms to KnowHow did artists respond to the New Culture Movement?

What is guohua, or new national painting?

How did modern Chinese woodcuts differ from earlier paintings and prints?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

Republic of China

Chinese Nationalist Party

Chinese Communist Party

May Fourth Movement

Treaty of Versailles

Tiananmen Square, Beijing

Second Sino-Japanese War

Massacre of Nanjing

New Culture Movement

The Lingnan School

New national painting, guohua

The Shanghai School

Modern woodcut movement

Double Ten Festival

Composite photography

Learn more

Julia F. Andrews and Shen Kuiyi, eds., A Century in Crisis: Modernity and Tradition in the Art of Twentieth-Century China (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1998).

Julia F. Andrews and Shen Kuiyi, The Art of Modern China (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2012).

Chinese Art: Modern Expressions (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2001).

Michael Sullivan, Art and Artists of Twentieth-Century China (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1996).