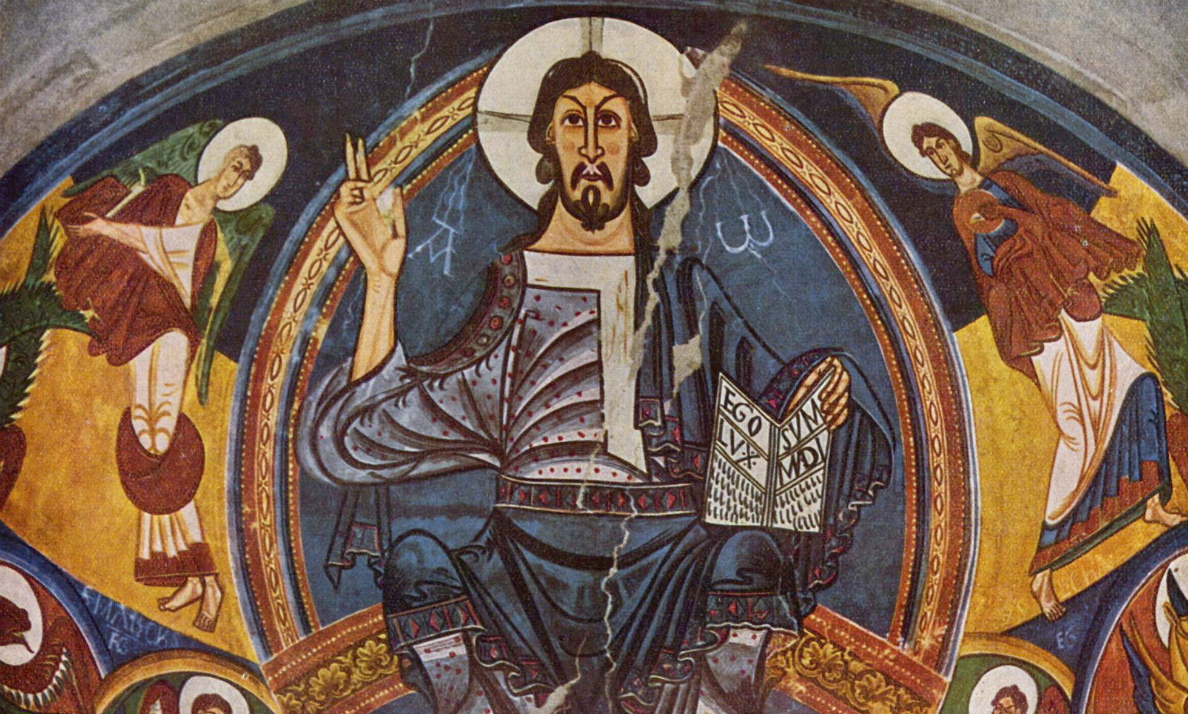

Byzantine art: an introduction

Read Now >Chapter 36

Medieval Materiality across the Mediterranean, 900–1500 C.E.

Borghorst reliquary cross, mid-11th century, gold plate on wooden core, gems, rhinestones, silver-pearls, rock crystals, purple silk, relics, 41.1 x 28.4 cm, St. Nicomedes Church, Steinfurt, Germany

At the center of this golden cross is a rock crystal flask. The crystalline object was originally carved in tenth-century Fatimid Egypt, where it was prized for its transparency, durability, and luminosity. Over the next hundred years, it found its way to Borghorst, a city in northwestern Germany, either as a diplomatic gift, a souvenir of travel, or even a spoil of war. There, it was likewise valued for its beauty and clarity, as well as its distant origins. For its new Christian owners it also carried spiritual significance, as the crystal material was linked to the transcendent quality of Christ. It offered a perfect medium to adorn, protect, and magnify the relics of the True Cross encased within the Fatimid rock crystal vessel.

The preparation for the Passover festival, from the Golden Haggadah, c. 1320, northern Spain, probably Barcelona (British Library, MS. 27210, fol. 15 recto)

As this cross and its rock crystal show, works of art in the Middle Ages were valued for the imagery they present and the materials in which they were made. By paying attention to the materiality of a work of art, we can learn how the materials themselves helped to create meaning.

Map of the Mediterranean c. 1000 C.E. (underlying map © Google)

This chapter examines 600 years of portable objects patronized by the Christian, Muslim, and Jewish communities of the Byzantine Empire, early Islamic dynasties, and western European kingdoms. Rather than studying these works chronologically or geographically, as they are most often considered, they are grouped here by medium—purple-dye, gold, bronze, ivory, and precious and semi-precious stones. In so doing, we see not only the significance of the media themselves, but also the flow of trade routes, labor, and technologies across the shores of the medieval Mediterranean. Although used and valued in different ways, these potent materials were equally prized by Byzantine elite, Muslim caliphs, and kings and noblemen of medieval Europe.

As a primer to this chapter, the following essays provide a brief overview of the regions, empires, and dynasties for whom these materials carried so much value.

Read introductory essays

Introduction to the Middle Ages: The visual arts prospered during Middles Ages, which created its own aesthetic values.

Read Now >/4 Completed

Purple dye

The secretions of the murex, a sea snail found on the shores of the Mediterranean, yield dyes with a rich purple hue. By the early second millennium B.C.E., the Minoans on Crete developed the manufacture of this purple dye into a large-scale industry, exporting purple-dyed textiles as well as the labor-intensive technology for their production. Over one thousand years later, in ancient Rome (8th century B.C.E.–5th century C.E.), items colored with the murex dye had become exclusively associated with imperial power and wealth.

Left: Jesus clad in rich purple and gold silks, Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna (Italy), built c. 500, renovated 560s (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); right: Emperor Nikephoros III Botaneiates wearing imperial purple and gold silks, Homilies of John Chrysostomos, c. 1071–1081, tempera and gold on vellum (Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris, MNs. Coslin 79, fol. 2r)

With the Christianization of the Empire, these associations extended also to Christ, the heavenly King, who was often rendered in purple-dyed silks with bands of gold. Under the subsequent Byzantine Empire (330 C.E.–1453 C.E.), murex purple was so highly prized that its production was strictly controlled and limited to the imperial court.

Byzantine emperors gifted purple murex silks to aristocrats or delegations from foreign courts as a sign of imperial favor. As a result of their prestige, purple-dyed silks and manuscripts were among the most expensive and sought-after luxury objects across the Mediterranean.

This Marriage contract of Emperor Otto II and Theophano imitates expensive Byzantine purple manuscripts and textiles using more commonly available, less expensive pigments, 14 April 972, parchment, black and gold ink, c. 155 x 40 cm (Niedersachsisches Staatsarchiv, Wolfenbüttel, Germany)

Murex purple dye was so highly valued, that those who could not afford the precious material tried to imitate it. In 972, Byzantine empress Theophano, niece of the Byzantine emperor, married Otto I, heir to the Holy Roman Empire. To commemorate their union, the Ottonians crafted a marriage contract imitating Byzantine purple manuscripts and textiles with more commonly available pigments. They further adorned the contract with roundels (circles) enclosing pairs of animals and hybrid creatures, imagery commonly found on Byzantine embroidered purple silks. This masterful imitation of Byzantine purple-dyed manuscripts and textiles conferred legitimacy on the less-powerful Ottonian household.

Folio from the Blue Qur’an, second half 9th–mid-10th century, gold and silver on indigo-dyed parchment, made in Tunisia, possibly Qairawan, 30.4 x 40.2 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Similarly, the folios of the Blue Qu’ran, dyed with indigo, have also been understood as an appropriation of Byzantine purple-dyed manuscripts. By imitating the Byzantine murex dye, the Qur’an would have showcased the imperial pretensions of its early Islamic patrons.

Arabic inscription in gold on blue ground in the mihrab, Great Mosque at Córdoba, Spain (photo: wsifrancis, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

However, it is more likely that the manuscript draws on an established Islamic tradition of gold inscriptions on blue grounds, as seen in the mosaics of the Dome of the Rock and the Great Mosques of Damascus and Córdoba. Although executed in different materials and not necessarily produced in competition with the products of the Byzantine Empire, the pages of the Blue Qu’ran would have achieved a similar impressive effect.

Read essays about objects made with purple dye

The Vienna Genesis: The purple parchment with its text written in silver Greek capital letters gives this luxury manuscript a dramatic effect.

Read Now >

Byzantine purple silks: The alternation of gold and purple in imperial silks enhanced the radiance of the prestigious fabric.

Read Now >/2 Completed

Gold

Detail of Mansa Musa (ruler of the Kingdom of Mali) holding a golden orb and the Sahara Desert, with the Mediterranean above, in the Catalan Atlas of Abraham Cresques, 1375, made in Majorca, Spain (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Ms. Espagnol 30)

Gold lay at the heart of a global medieval economy connecting western Africa with the Mediterranean, West Asia, and western Europe. West African communities leveraged their abundant resources in gold in exchange for materials less prevalent locally, in particular for copper which they believed had particular spiritual efficacy. As a result, gold—along with other goods such as glass beads, ivory, and textiles—moved across Saharan trade routes, reaching the shores of the Mediterranean. Medieval artists in turn produced sumptuous golden works of art which inspired feelings of awe and wonder.

Map Showing Global Trade Networks, particularly trans-Saharan routes and their linkages. Map made for the exhibition Caravans of Gold.

A tenth-century silver-gilt and enamel Byzantine icon (below) uses gold to capture the ethereal qualities of its sacred subject. The icon renders the Archangel St. Michael through lavish materials, including enamel, gemstones, and gold filigree. His face and hands, raised in a gesture of intercession, emerge from the surface having been hammered into relief from the reverse side through a technique called repoussé. We can imagine the power of this multimedia icon when viewed within the dimly lit interior of a church. As candle flames flickered across its surface, the shimmering gold of St. Michael’s face and halo would have been animated in response, his eyes glittering into life.

Employing masterful techniques, the artists producing the icon of St. Michael and other gilded works harnessed gold’s reflective qualities to display them to full effect. It is no surprise that goldsmiths were among the premier artists of the Middle Ages, singled out for praise in the scant surviving documentation of medieval artists.

Panel with half-figure of St. Michael, late 10th- first half of 11th century, Constantinople, silver-gilt, gold cloisonné enamel, stones, pearls, glass (Treasury of San Marco, Venice; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Watch videos and read essays about objets made with gold

The Golden Haggadah: The extensive gilding on this Hebrew manuscript represents a luxury aesthetic shared by Jews and Christians in early fourteenth-century Catalonia.

Read Now >

Gold in the Qur’an: Although capturing the transcendent nature of Allah, the presence of gold in Qur’anic manuscripts also inspired anxieties over its improper use.

Read Now >

Taddeo Gaddi, Saint Julien: By applying gold leaf to a wooden panel painting, medieval painters captured the eternal heavenly realm.

Read Now >

Medieval Goldsmiths: Using a range of metalworking techniques, goldsmiths produced impressive gold and silver objects.

Read Now >

Belém Monstrance: Threatened with military violence, the Sultan of Kilwa in present-day Tanzania was forced to hand over the gold used to make this monstrance in recognition of the overlordship of King Manuel I of Portugal.

Read Now >/5 Completed

Bronze

Bronze doors, 1015, commissioned by Bishop Bernward for Saint Michael’s, Hildesheim, Germany (photo: Bischöfliche Pressestelle Hildesheim, CC0)

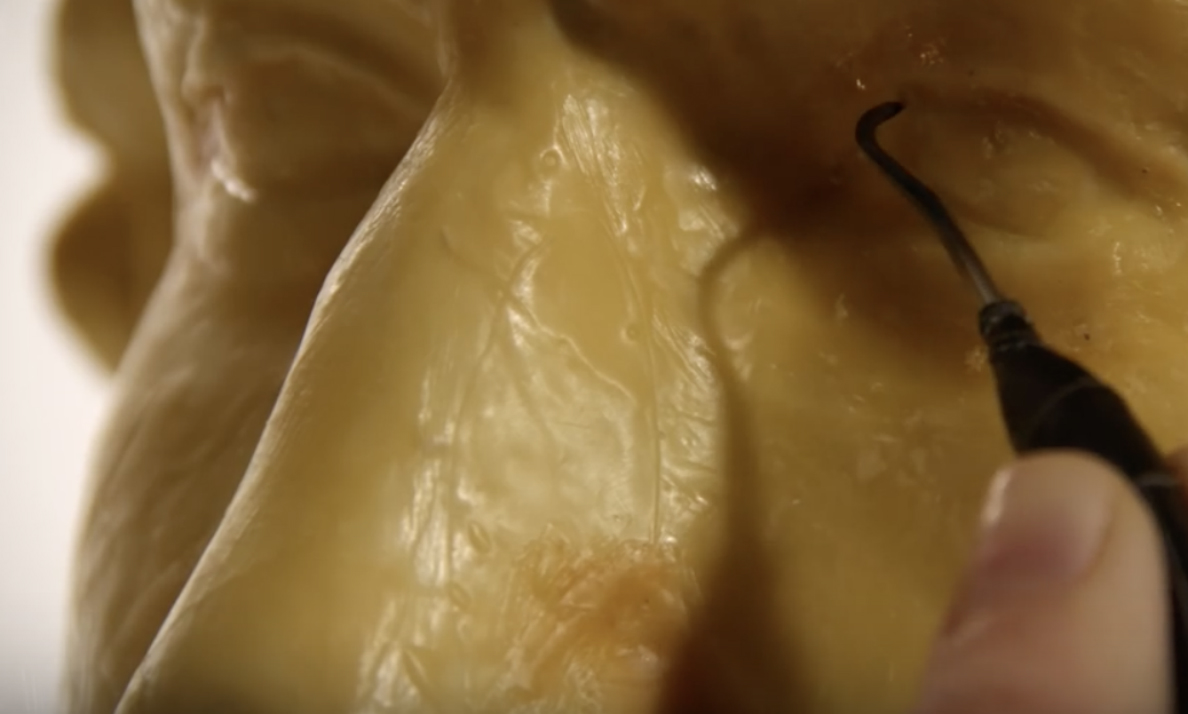

Although not as precious as gold, bronze (a metal alloy) became one of the most popular media for three-dimensional sculpture in the Middle Ages. With its proximity to copper mines, necessary for the production of bronze, St. Michael’s Monastery at Hildesheim in Northern Germany became a primary center of the medieval bronze industry. To produce monumental bronze structures, the craftsmen at Hildesheim revived the lost-wax casting technique (discussed in detail below), a technology not used on such a large scale since the end of Roman rule in Europe in the fifth century. Following this technique, once the molten bronze had been poured into the mold, the mold was broken to reveal the hardened bronze material. It was as if the solid material appeared ex nihilo, or out of nothing. Seemingly imitating the very act of divine creation, the complex casting technique imbued the object with an aura of the marvelous. This is especially evident in one of the most famous works produced at Hildesheim, the monumental bronze doors with scenes from the Old and New Testament. By representing the Creation of Adam and Eve through the bronze medium, the artist drew a direct parallel between divine and artistic creation.

Watch videos about bronze objects

Bronze Casting using the “Lost Wax” Technique: Variations on this technique have been used around the world to produce bronze sculptures.

Read Now >

Hildesheim bronze doors: Bishop Bernward’s bronze doors at Hildesheim are the earliest known freestanding bronze sculptures in western medieval Europe.

Read Now >/2 Completed

Ivory

Detail of Mansa Musa and the Empire of Mali in the Catalan Atlas of Abraham Cresques, 1375, made in Majorca, Spain (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Ms. Espagnol 30)

Along with gold, trans-Saharan trade routes also brought ivory to medieval artisans in the Islamic world, Byzantium, and western Europe. Merchants from the Empire of Mali carried tusks across the savannahs of West Africa to trading centers along the Niger River bend. There, they were included in camel caravans stopping at cities like Sijilmasa, or traveling all the way to the North African coast where they met with the traders of the Mediterranean sea trade.

Pyxis of al-Mughira, possibly from Madinat al-Zahra, AH 357/ 968 CE, carved ivory with traces of jade, 16cm x 11.8 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In the 10th century, the so-called “ivory century,” the craft of ivory carving flourished in Al-Andalus, Constantinople, Fatimid Egypt, and the Ottonian Empire. Ivory containers, or pyxides, with vegetal and animal carved decoration, were produced in workshops at the royal courts of Córdoba and Madinat al-Zahra in Muslim Spain. Containing precious items, such as perfumes and spices, these pyxides frequently served as gifts within the royal court. Long after the collapse of the Umayyad dynasty in Spain, they were reused as containers to hold Christian relics.

Enthroned Virgin and Child, c. 1260–80, Paris, France, 18.4 x 7.6 x 7.3 cm (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

To the medieval Christian, the color and surface of ivory connoted notions of purity and chastity, qualities associated with the Virgin Mary. It is no surprise then that when ivory reappeared on European markets in the thirteenth century following a long period of scarcity, ivory production focused on statuettes of the Virgin and Child. The sculptor of this statuette sensitively carved the figures, exploiting the tusk’s natural curvature to evoke the Virgin’s inclination toward her son. This figurine undoubtedly served as an object of personal worship. As the devotee cradled the statuette in their hands, we can imagine that its smooth surface appealed to their sense of touch.

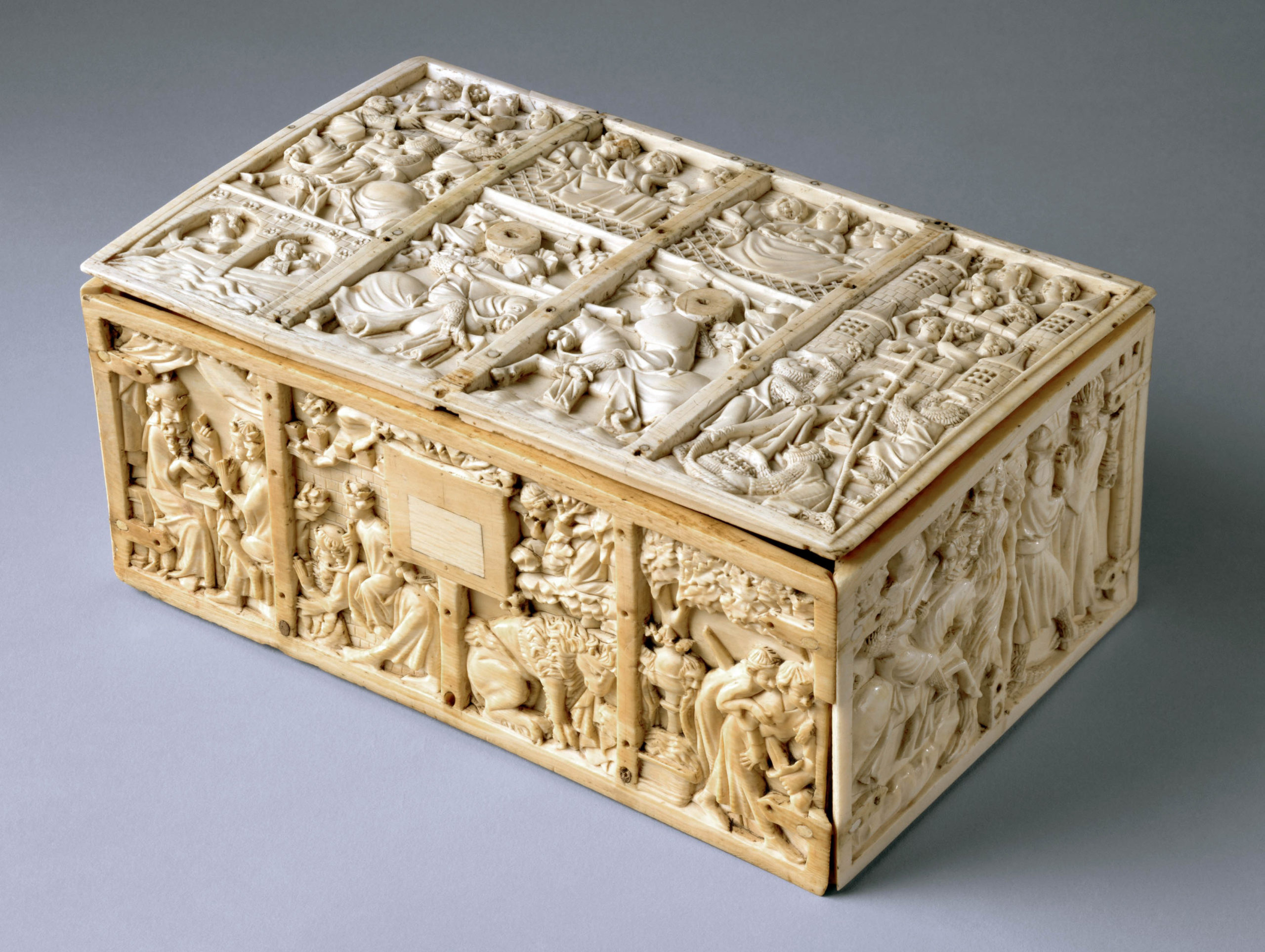

Casket with Scenes from Romances, c. 1310–30, French, ivory, 10.9 x 25.3 x 15.9 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Secular objects such as game pieces, mirrors, combs, and caskets with scenes from medieval romances similarly exploited the precious ivory material. These works invite tactile engagement both through their iconography of courtly love and their textured surfaces.

Read essays about ivory objects

Pyxis of al-Mughira: This exceptionally carved pyxis reveals the remarkable textures and patterns ivory carvers could produce with this luxury medium.

Read Now >

Ivory casket with scenes from medieval romances: The invitation to touch can be traced across the surface of this ivory box through its iconography of romance and the inviting texture of the material itself.

Read Now >/2 Completed

Precious and Semi-Precious Stones

From sapphires, amethysts, and emeralds, to rock crystals and pearls, precious and semi-precious stones were highly valued for their color and luminosity. Equally, however, medieval viewers prized these materials for their medicinal properties and sacred resonances. According to medieval lapidary texts, precious and semi-precious stones embodied the characteristics of sacred figures, such as the Virgin Mary and Christ, or carried properties of healing or protection for their owners. These potent stones were therefore powerful adornments for jewelry and weapons, or religious objects such as reliquaries, icons, and crosses.

Bracelet, early Byzantine, 500–700, Constantinople (?), gold, silver, pearl, amethyst, sapphire, opal, glass, quartz, and emerald plasma, c. 4 x 8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Precious and semi-precious stones moved easily around the medieval Mediterranean, offered as gifts in diplomatic exchanges, donated to monasteries and churches as acts of piety, or looted in times of war. Following Venice’s sack of Constantinople in 1204, for example, the Venetians seized many of the precious stones and prized vessels from the capital city, deeming them valuable for their materials and messages of Venetian triumph. Today, you can see several Byzantine chalices made of reused antique stones and Islamic glass preserved in the treasury of San Marco in Venice.

Head (detail), Reliquary statue of Sainte-Foy (Saint Faith), late 10th to early 11th century with later additions, gold, silver gilt, jewels, and cameos over a wooden core, 33-1/2 inches (Treasury, Sainte-Foy, Conques) (photo: Holly Hayes, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Similarly, the tenth- and eleventh-century reliquary of St. Foy from the Abbey Church of St. Foy in Southern France is encrusted with more than ninety jewels. St. Foy’s crown and robes include Greek and Roman, Carolingian, and Ottonian cameos and engraved stones, all offered as gifts to the saint. The reuse of gems of antique origins associates the reliquary with royal prestige, as the owners of such gems were almost exclusively imperial.

Read essays about precious and semi-precious stones

Wearable art in Byzantium: Worn on the body, semi-precious and precious stones communicated complex messages about social identity and religious beliefs as well as offered healing and protection to the wearer

Read Now >

Church and Reliquary of Sainte-Foy, France: According to the book of Miracles of St. Foy, compiled by eleventh-century pilgrim Bernard of Angers, St. Foy appeared to her devotees in dreams until they gave her the jewels she demanded.

Read Now >/2 Completed

Pearls

Rarer than gold and more difficult to attain, pearls were valued for their natural luster, pure white color, and perfect spherical shape. Moreover, believing pearls to be formed when lightning enters an oyster shell, Christian and Islamic texts alike celebrated them for their seemingly miraculous creation.

Hanging pearls suspended in lavish palaces, 8th century, mosaic, Great Mosque of Damascus, Syria (photo: american rugbier, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Medieval Arabic texts describe a well-known pearl called al-Yatima, meaning the Unique or the Orphan, as incomparable for its radiance and whiteness. According to one source, the Yatima was suspended from chains in the Dome of the Rock during the reign of Umayyad caliph al-Walid. The Umayyads in Córdoba may have possessed the same pearl, displaying it in their caliphal palace in Madinat al-Zahra. The mosaics of the Umayyad Great Mosque of Damascus feature hanging pearl chains within the mosaic’s palatial structures. These suspended pearls may have heavenly associations, perhaps drawing on Qur’anic descriptions of pearl-structures in paradise.

Jeweled upper cover of the Lindau Gospels, c. 880, Court School of Charles the Bald, 350 x 275 mm, cover may have been made in the Royal Abbey of St. Denis (Morgan Library and Museum, New York; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Pearls were similarly used in both Christian and Jewish art to invoke an image of heaven. According to passages in the Book of Revelation, precious stones adorn the walls of the Heavenly Jerusalem, with twelve pearls symbolizing the twelve apostles in the heavenly city. The jewel encrusted covers of the Lindau Gospels, a masterpiece of medieval Christian imperial patronage, encapsulate this imagery.

Rimonim, 15th century, originally from the Synagogue of Cammarata, Sicily before 1493, currently held in the Treasury of the Cathedral of Palma de Majorca, Spain

Likewise, these fifteenth-century Sicilian rimonim, or finials designed to adorn the wooden staves of the Torah, a remarkable testament to Jewish culture in Sicily prior to their expulsion in 1493, similarly evoke the imagery of the Heavenly Jerusalem through their materials. While many rimonim are round in shape, likely due to the meaning of the Hebrew word rimon, or pomegranate, this medieval pair takes the form of a tower, often used to connote the Heavenly Jerusalem by Jews and Christians since the early Byzantine period. Decorated with horseshoe arches and silver filigree, pearls, and other semi-precious stones, as well as bells suspended on chains, these rimonim would have visually and aurally announced the hope for a New Jerusalem as the Torah was processed throughout the synagogue.

Jan van Eyck, detail of Mary, Ghent Altarpiece (open), completed 1432, oil on wood, 11 feet 5 inches x 7 feet 6 inches (closed) (Saint Bavo Cathedral, Ghent, Belgium) (photo: Closer to Van Eyck)

Finally, in the Ghent Altarpiece, painter Jan Van Eyck paid remarkable attention to the materiality of objects, capturing with extreme accuracy the golden brocade of the attendants’ garments, the metalwork on the Virgin’s crown, and the abundant pearls and gemstones adorning all of the figures. The accumulation of precious stones in the robes of church officials and worshippers indicates the wealth of the Burgundian court. At the same time, the density of jewels appearing in the stream surrounding the Fountain of Life, as well as on the garments of the Virgin and God the Father, both radiant in gems, vividly depicts notions of paradise.

Read essays about objects with pearls

Lindau Gospels cover: The overwhelming presence of gemstones, gold, silver interlace, and enamel on the book covers, as well as Byzantine and Islamic silks on the inner and outer bindings, make this gospel book a masterpiece of the medieval jewelers’ art.

Read Now >

Jan Van Eyck, The Ghent Altarpiece: Van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece is a tour-de-force of craftsmanship in its attention to precisely rendering objects and their materials.

Read Now >/2 Completed

Whether prized for their physical properties, rarity, origins and history, metaphorical significance, or the skill required to work with them, materials were integral to the meaning and function of medieval works of art.

Key questions to guide your reading

How are the meanings of works of art tied to their materials?

How do artisans celebrate and emphasize the material of a work of art?

How does war, diplomacy, and trade facilitate the exchange of raw materials, artistic techniques, artists, and ideas?

How are these materials perceived and used in works from other periods of history that you’ve studied? How has their meaning and/or value changed? Why?

Jump down to Terms to KnowHow are the meanings of works of art tied to their materials?

How do artisans celebrate and emphasize the material of a work of art?

How does war, diplomacy, and trade facilitate the exchange of raw materials, artistic techniques, artists, and ideas?

How are these materials perceived and used in works from other periods of history that you’ve studied? How has their meaning and/or value changed? Why?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

alloy

iconography

lapidary

lost-wax casting

medium (pl. media)

materiality

murex

pyxis (pl. pyxides)

reliquary

repoussé

silver-gilt

Learn more

Read about late medieval multimedia objects

Caravans of Gold, Fragments in Time: Art, Culture, and Exchange across Medieval Saharan Africa

Cynthia Hahn and Avinoam Shalem, eds. Seeking Transparency: Rock Crystals Across the Medieval Mediterranean (Berlin: Verlag, 2020).

The Lindau Gospels (fully digitized)

The Gold Road, interactive map

Ittai Weinryb, The Bronze Object in the Middle Ages (Cambridge University Press, 2016)

Learn about post-medieval objects in ivory, feathers, brass, and more