Orientalism: an introduction

Read Now >Chapter 68

Modern Art, Colonialism, Primitivism, and Indigenism: 1830–1950

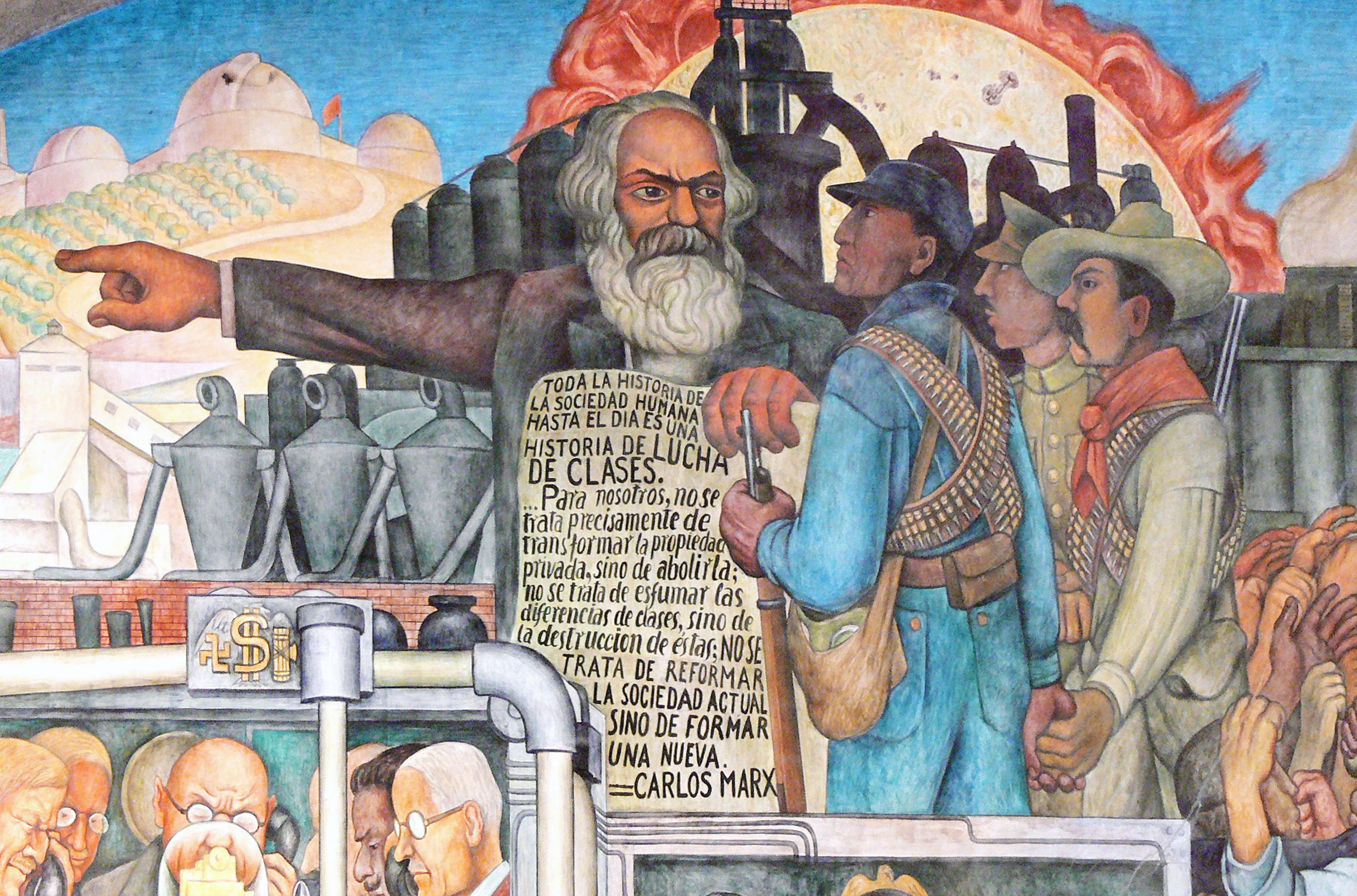

Consider the enormous suite of murals entitled The History of Mexico that Mexican artist Diego Rivera painted for the National Palace in Mexico City. Rivera had studied modern art in Europe before returning to Mexico City and helping to launch the Mexican Muralist movement. His History of Mexico is considered an important part of the “Western” canon of modern art.

Coatlicue, c. 1500, Mexica (Aztec), found on the SE edge of the Plaza mayor/Zocalo in Mexico City, basalt, 257 cm high (National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Now let’s turn to a different example: the snake-skirted sculpture of Coatlicue, an Aztec goddess, that stands more than 10 feet tall and is expertly carved. This important sculpture has long been associated with the so-called non-Western canon. But herein lies a paradox: both works are hecho en México (“made in Mexico”) and they reside within miles of one another in the same city. How is it that one is considered Western and the other non-Western? This is only one of the many paradoxes we will unravel in this chapter as we survey a history of European and American modern art from the 1830s through the 1940s within a broader global context and specifically in relation to colonialism’s impact on the history of modern art.

The "West"

The “West,” as cultural theorist Stuart Hall described it, is a fiction. While it is loosely based on geography—some countries in the western part of Europe, and at a later point in time the United States, Canada, and Australia—it is more of a designation about what constitutes modern, urban, industrialized societies than a geographic reality. Ideas of “the West” evolved because of European colonialism and industrialization.

It was in certain European countries (primarily France, Germany, Italy, Russia, and England) where the concept of modern art emerged (during the 19th and 20th centuries). Modern art was rooted in part in a rejection of the European tradition’s high regard for the naturalistic art of ancient Greece and Rome (which was held up by the art academies of Europe as the pinnacle of culture).

Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907, oil on canvas, 243.9 x 233.7 cm (Museum of Modern Art, New York, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Modernism, however, refers to more than an assault on European artistic traditions, it is also the art of industrial, capitalist societies predicated upon networks of trade expanded through colonization. Modernism became synonymous with the West, and the West, defined in opposition to all that was non-European or non-West. Modernism also became synonymous with predominantly white European nations first, then later with North America (or at least parts of it) and became an affirmation of the West’s own assessment of its superiority. A racial hierarchy was thereby put into place. If industrial capitalist societies were seen to have “evolved,” the remainder—a huge swath of the globe—became viewed as underdeveloped, unevolved, and existing in a “primitive” state of social organization. Correspondingly, the art of certain non-European countries came to be seen as the product of primitive societies.

The themes chosen for this chapter are by no means meant to be comprehensive but instead intended to highlight how the visual culture of Western modernity was broadly transformed by these structures and encounters. Loosely organized by both chronology and geography, each section plots the trajectory of modernism as it is impacted by various nations, states, and countries often under the control of European countries.

As you read this chapter, questions to consider are: why were so many European artists drawn to the so-called exotic or primitive art of non-European countries if those societies were argued to be inferior? In the emulation of so-called primitive art by Euro-American modernists, was there an implicit affirmation of the superiority of Western culture? How, in turn, did non-European artists respond to these cultural intersections?

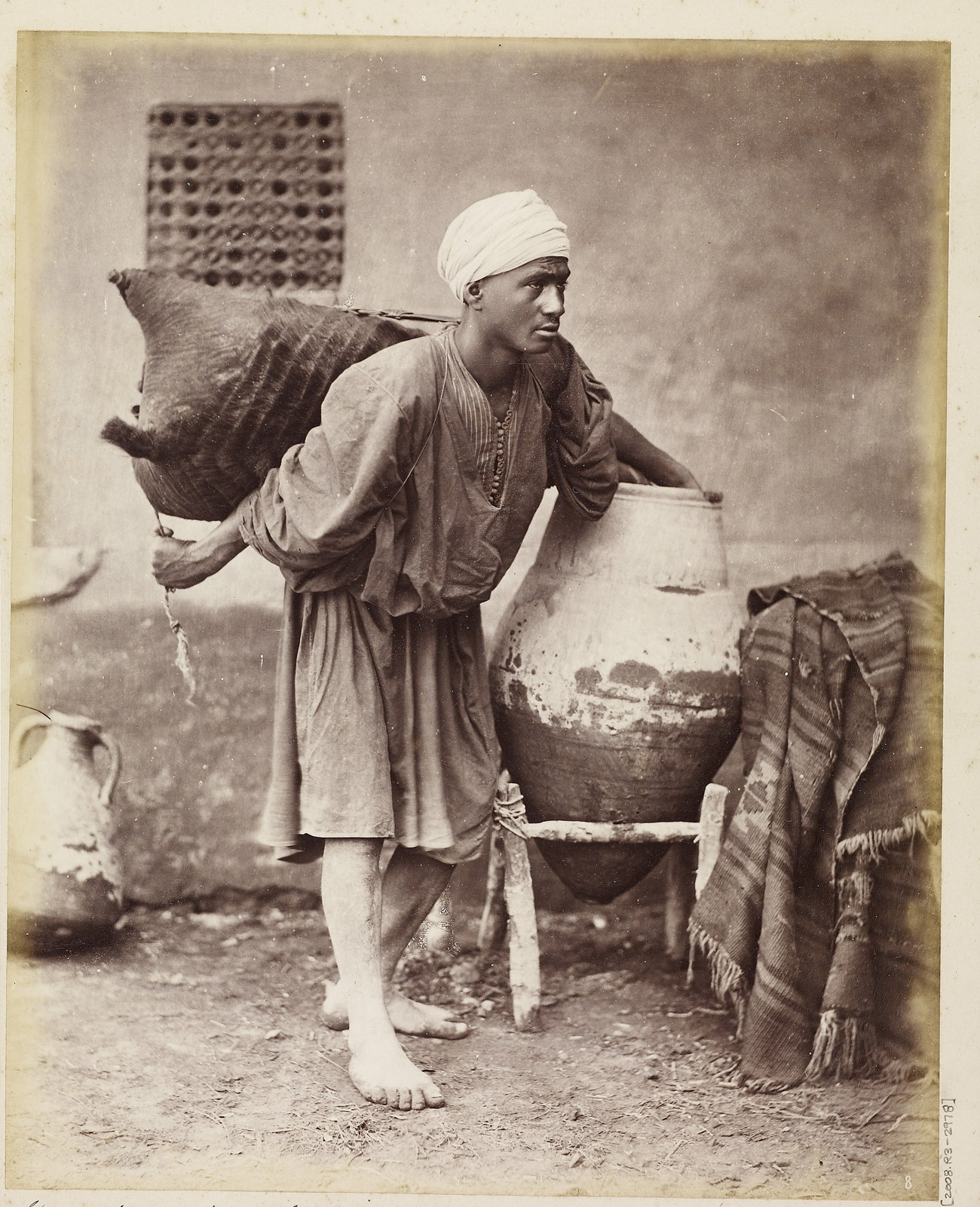

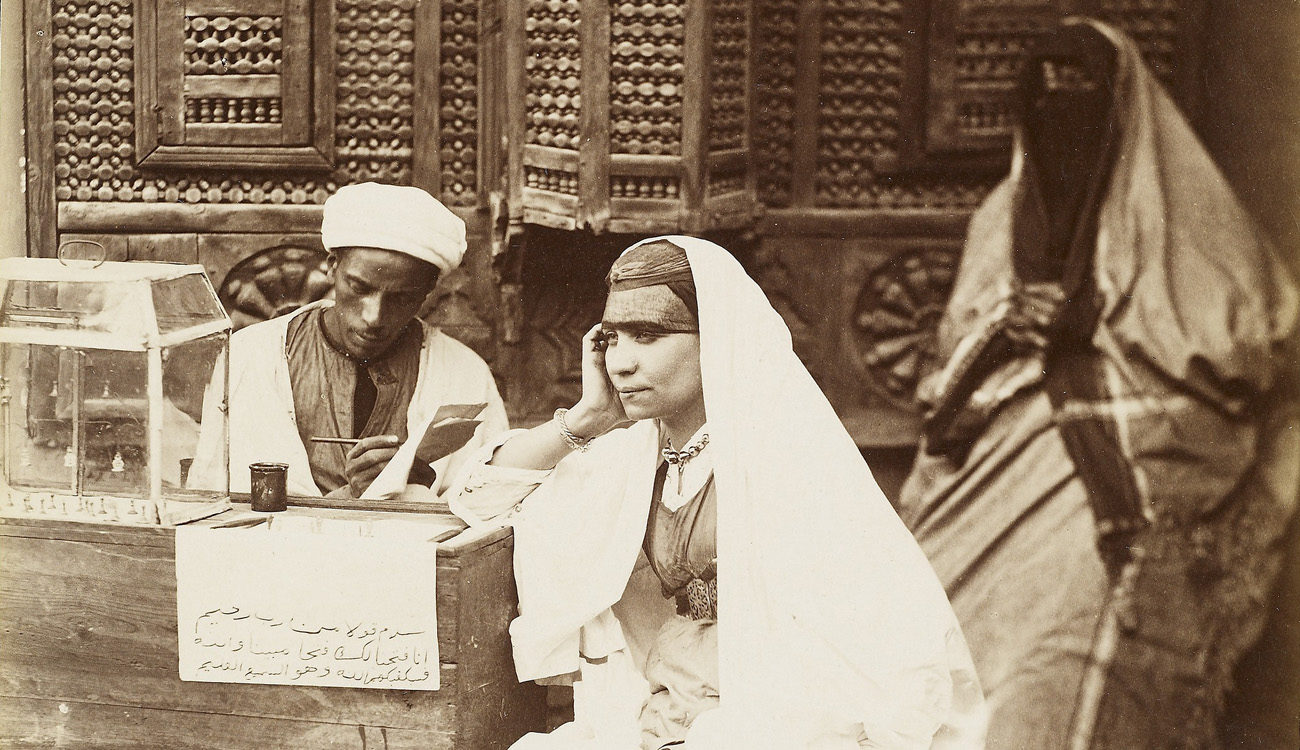

Orientalism

We first turn to Northern Africa and West Asia, initially described by Europeans as the “Orient” because it was largely situated just east of western Europe. The term “orientalism,” as Nancy Demerash writes in her essay on the topic (that you will read below), “reflects a Western European view of the ‘East’, and not necessarily the views of the inhabitants of these areas.” Associated with the French Romantic movement, Orientalism in painting describes not so much a style as subject matter. West Asian and northern Mediterranean cultures such as Arabia and Algeria became a rich source of new subject matter for artists in the 19th century who increasingly turned their attention away from the classical (ancient Greek and Roman) past, seeking new frames of reference. “Rome,” as the painter Eugène Delacroix famously intoned, “is no longer to be found in Rome.”

Eugène Delacroix, Women of Algiers, c. 1832–34, oil on canvas, 46 x 37.8 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

As is typical of Orientalist painting, Eugène Delacroix’s travels to North Africa did not produce so much a record of what he saw but a fantasy of exotic cultures. The inhabitants of many new European colonies in the aftermath of Emperor Napoleon’s territorial expansion, were, for the French at least, emblems of the exotic, the wondrous, the strange (even dangerous!). Like the later concept of Primitivism (discussed below), Orientalism is a product of colonialist encounters and its impact on art is felt throughout the late eighteenth to the twentieth century. While Orientalism refers specifically to Western views of Northern Africa and West Asia, it shares with Primitivism a rather generalized view of “non-Western” cultures—viewing them merely as expressions of their race and unenlightened status Orientalism and Primitivism cannot be separated from colonialism. It could be argued that both are cultural expressions of colonialism.

Watch videos and read essays about Orientalism and the rejection of the classical tradition

Baron Antoine-Jean Gros, Napoleon Bonaparte Visiting the Pest House in Jaffa: Gros is most well known for recording Napoleon’s military campaigns (such as in Egypt), which proved to be ideal subjects for exploring the exotic, violent, and heroic.

Read Now >

Staging the Egyptian Harem for Western Eyes: To fill a visual void, westerners relied on fantasies of harem life, for which opera libretti and novels offered, material. For the photographer the same was also true.

Read Now >

Eugène Delacroix, Women of Algiers in Their Apartment: Delacroix’s orientalist fantasy exhibited to great acclaim in the Paris Salon.

Read Now >/4 Completed

Primitivism and the Rejection of the Classical Tradition

If Orientalism was primarily concerned with depictions of non-Western subjects, “Primitivism” is an emulation of style erroneously construed as simplistic, naïve, child-like, and un-trained. The term refers to the culture of any non-Western country, specifically those of Africa, Mesoamerica, South America, and the Pacific. No matter how sophisticated it may have been visually, or how complex its symbolism, non-European art was often deemed “primitive,” simply because it was non-European! As Drs. Kramer and Grant note in their essay below, “This definition contains a basic contradiction: the primitive is admired and even seen as a model, but at the same it is also presumed to be inferior, because it is not fully developed.”

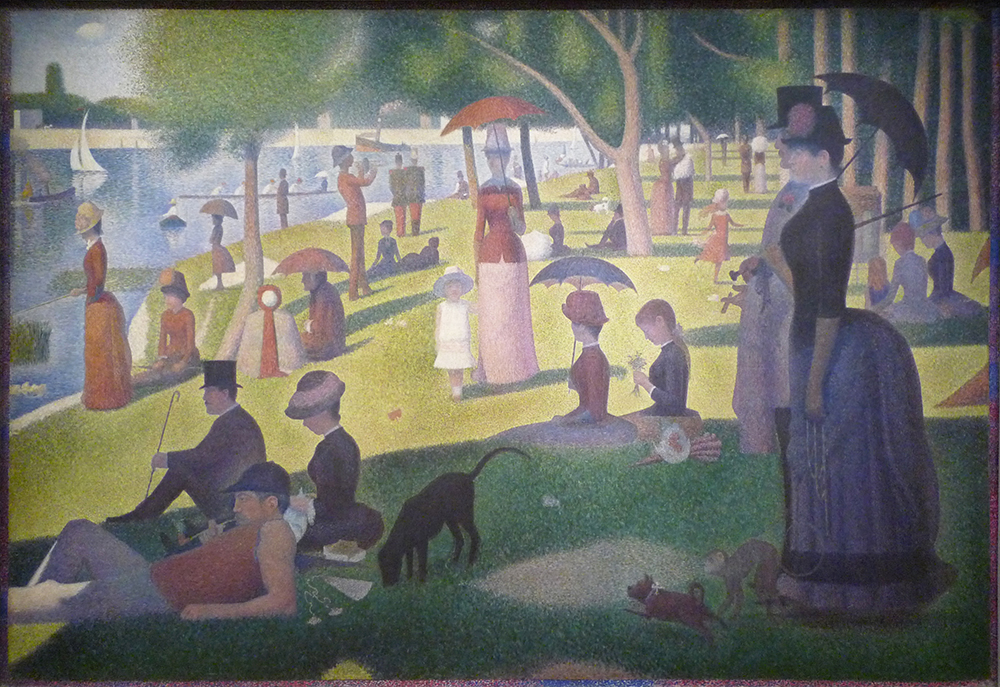

Georges Seurat, A Sunday on La Grande Jatte—1884, 1884–86, oil on canvas, 81-3/4 x 121-1/4 inches (207.5 x 308.1 cm) (The Art Institute of Chicago)

There is another paradox at work here: despite the fact that ideas of European superiority were seen to rest upon a heritage of Greco-Roman antiquity, it was clear by the middle of the nineteenth century that myths of antiquity were growing ever more distant from the emerging modern world. But it was the very process of an evolving culture in the Western tradition (set against the belief that so-called primitive cultures remained largely static) that underwrote its claims to greatness. It is also important to note that the classical heritage was never fully jettisoned. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century artists like Edgar Degas, Georges Seurat, or Pablo Picasso revisited the classical model in revised form.

This transition from the classical past into the modern present has traditionally been presented in art history as an unbroken and linear march through stylistic movements culminating in abstract art in the twentieth century. But the history of modern art cannot so easily be disentangled from larger global historical factors—the occupation and subjugation of countries in Africa, Asia, the Pacific, and the Americas. As we shall see in what follows, it was to the visual cultures of countries under European colonial rule—the so-called non-West—to which artists turned as they struggled to undo the rules of classical art taught in art academies and invent new visual languages for the modern world and modern experience.

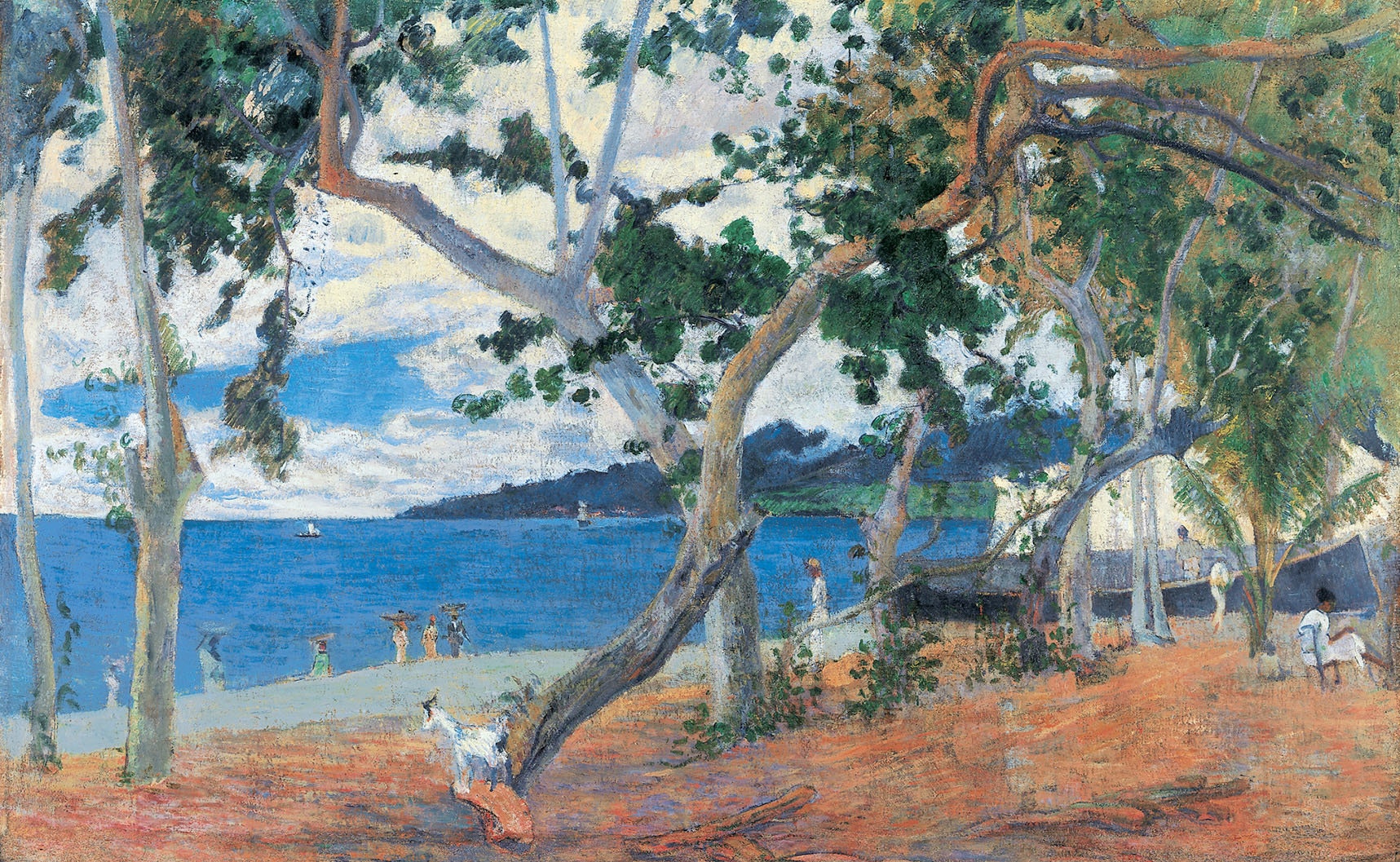

Primitivism and Modernism

The study of art and artifacts from European colonies first began with the newly emergent disciplines of ethnography and ethnology in the nineteenth century. These disciplines existed for the purpose of studying cultures and people who now found themselves under European rule. Anthropologists were the first to acknowledge the artistic merit, along with the ethnological significance, of artifacts (or at least those that conformed to Western standards) discovered during and in the aftermath of colonial occupations in the nineteenth century. First displayed in the context of anthropological and ethnographic exhibitions, a number of these objects, many of them startlingly abstract sculptures from West African countries and kingdoms, soon found their way into the studios of artists. As you will discover in reading the essays below, both Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso among others began to collect and then emulate the visual properties and representational strategies they perceived in tribal masks and artifacts that turned up in curio shops and ethnographic museums like the Musée d’ Ethnographie du Trocadéro in Paris. Other artists, like Paul Gaugin, not satisfied with merely the objects, wanted to experience the culture itself and so set out to explore and live with the colonized peoples of the Caribbean and South Seas islands.

Paul Gauguin, The Mango Trees, Martinique, 1887, oil on Canvas, 86 × 116 cm (Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam)

Primitivism was not confined to merely stylistic borrowings however; Western artists associated ideas of irrationality and strangeness with so-called Primitive artworks and it was this conceptual framework that underpinned the development of early twentieth-century avant-garde movements such as the anti-art movement Dada.

Poster for the opening of the Cabaret Voltaire, 1916, lithograph by Marcel Slodki (Kunsthaus Zurich, image: public domain)

Dada’s beginnings in Zürich during the First World War were characterized by a range of African-inspired performances: masks, costumes, and chanting in “primitive” dialect were key features of Cabaret Voltaire.

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, 1917/1964, glazed ceramic with black paint (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art)

Even the readymades of Marcel Duchamp are not immune to a primitivist sensibility. Could the very idea of appropriating a mass-produced industrial object, such as Duchamp’s infamous Fountain, 1907, a functional object removed from its context and de-functionalized as it was transformed into an object of art (precisely what was often done to the art of Africa) be understood as an allegory of the logic of primitivism itself?

Watch videos and read essays about primitivism and modernism

Édouard Manet, Olympia: This painting shocked audiences with its mocking of the classical past.

Read Now >

Primitivism and Modern Art: an introduction to what makes primitivism a concept that is both intellectually and morally complex.

Read Now >

The Reception of African Art in the West: Initially, “Westerners” saw African art as a mere “curiosity,” but this began to change with the advent of modernism.

Read Now >

Gauguin and Laval in Martinique: The artists’ journey to Martinique is a lesser-known chapter in the history of nineteenth-century French painting that connects to the country’s Caribbean colonies.

Read Now >

Henri Rousseau, The Dream: Its imagery of a woman lounging on a sofa in the jungle was as surreal then as it is today.

Read Now >

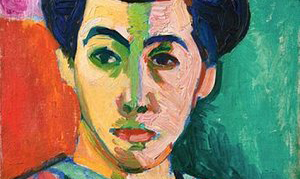

Fauvism: The Fauves’ interest in Primitivism reinforced their reputation as “wild beasts” who sought new possibilities for art.

Read Now >

Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon: In 1907, Picasso’s interest in African art was largely based on what he perceived as its alien and aggressive qualities.

Read Now >

Dada Readymades: Can readymades be understood as an allegory of the logic of primitivism itself?

Read Now >/8 Completed

Primitivism, Indigenism, and Modernism

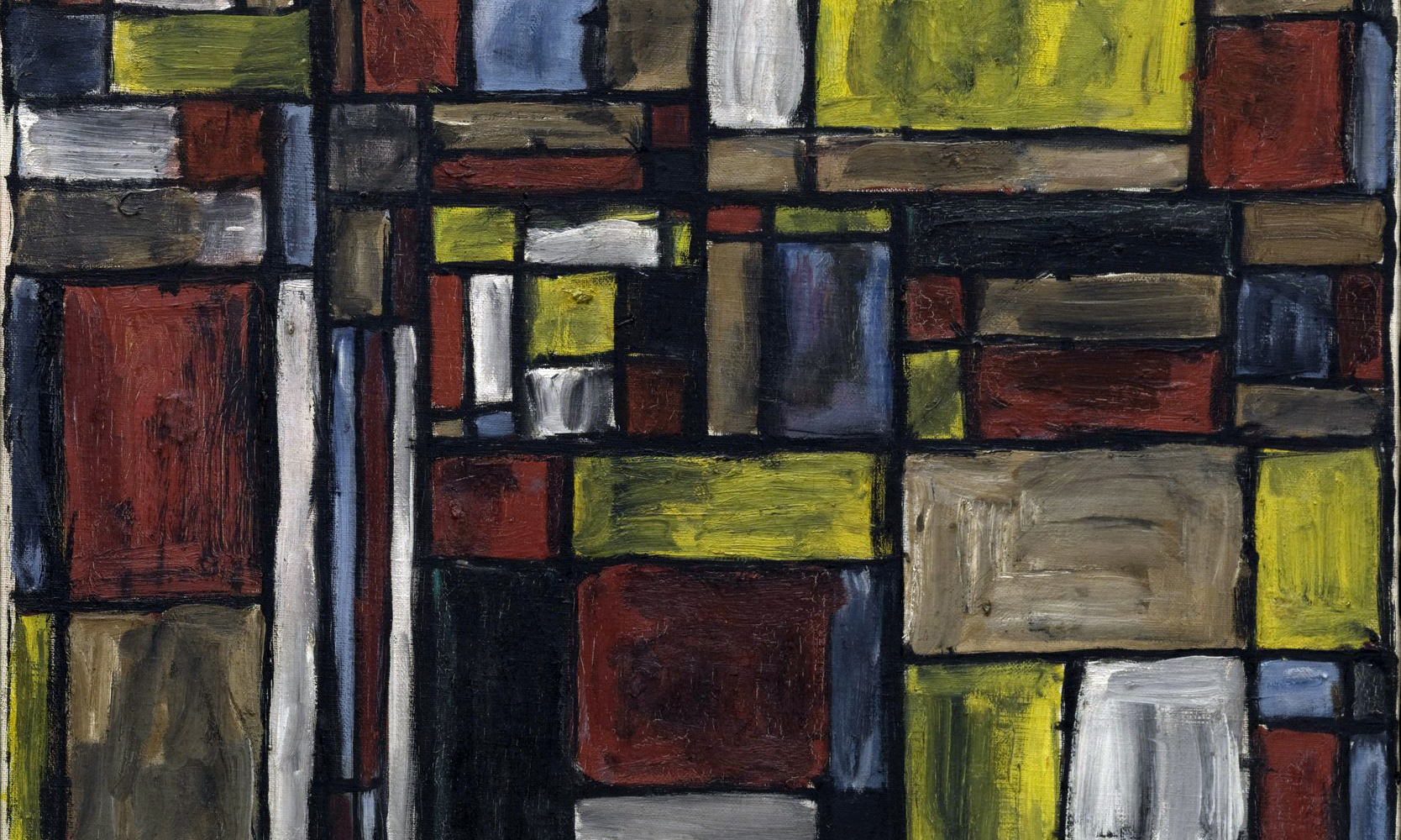

Carlos Mérida, Motivo Guatemalteco, 1919, oil on canvas, 97.5 by 71.5 cm

What happens when cultural appropriation takes place closer to home? Artists on the peripheries of the “West” like Carlos Mérida or Joaquín Gonzales-Torres subverted the hierarchies of Western and non-Western art as they became immersed in European abstraction and sought to integrate their own cultural heritage (marrying, for example, European modernist abstraction to pre-Columbian imagery) into an increasingly hybrid form of modern art. This final section looks at North and South American artists who draw upon Indigenous cultures of the Americas, sometimes in the service of reclamations of ethnic and racial identities severed through colonialism.

Aaron Douglas, Aspiration, 1936, oil on canvas, 152.4 x 152.4 cm (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco)

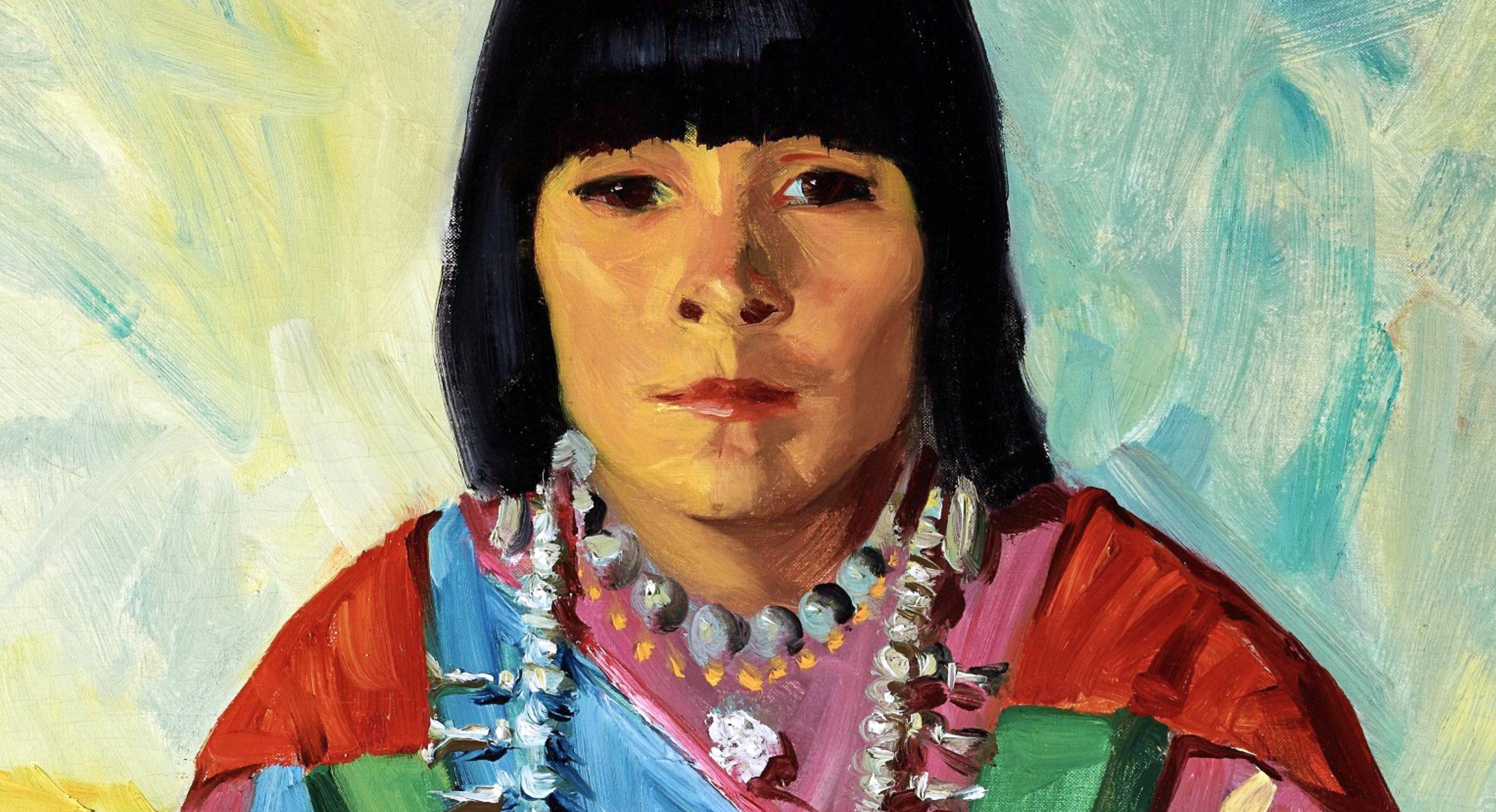

Aaron Douglas and Diego Rivera for example both sought to assert a lost ethnic or cultural origin through their art. In other cases there is a blending of the modern and the traditional, exemplified by the term pueblo modernism, as can be seen in art of the American southwest.

Joaquín Torres-García, Composition, 1931, 91.7 x 61 cm (The Museum of Modern Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The use of pre-Columbian motifs in the abstract paintings and sculptures of Joaquín Torres-Garcia (who performed his own inverted version of primitivism when he left his native Uruguay to study abstraction in Europe) is a further example of what could be termed indigenous primitivism, as is the work of Native American artists like Ma Pe Wi who re-appropriated the primitivist lens that had been trained upon them. Both artists, in other words, appropriated and then transformed cultural norms imposed upon them.

Velino Shije Herrera (Ma Pe Wi), Design, Tree and Birds, c. 1930, watercolor on paper, 25.25 x 17.75 inches (Newark Museum of Art)

This last section brings together a collection of essays and videos that create a picture of the early twentieth century in the Americas when ideas of the modern were embedded in ideas of identity, geography, and history.

Watch videos and read essays about Primitivism, Indigenism, and Modernism

Aaron Douglas, Aspiration: A mural depicting the history of Texas from an African American perspective.

Read Now >

Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Little Joe with Cow: Influenced by European modernism, American folk art, and Japanese ink drawings, Kuniyoshi combined whimsical, dreamy elements with a sense of foreboding or danger.

Read Now >

E. Martin Hennings, Rabbit Hunt: The Southwest became a hub for many white artists seeking “quintessentially American” subjects beyond New York and Chicago.

Read Now >

Velino Shije Herrera (Ma Pe Wi), Design, Tree and Birds: Native artists like Velino Shije Herrera developed a genre of watercolor painting on paper that connected European styles with Indigenous traditions of painting.

Read Now >

Robert Henri, Tom Po Qui (Water of Antelope Lake/Indian Girl/Ramoncita): The performance of Indigenous identity through the lens of early 20th-century Modernism.

Read Now >

Diego Rivera, The History of Mexico: In Rivera’s words, the mural represents “the entire history of Mexico from the Conquest through the Mexican Revolution . . . down to the ugly present.”

Read Now >

Geometric Abstraction in South America: Latin American geometric abstraction united international principles of modernist abstraction with local cultural traditions, and led to more participatory forms of art.

Read Now >/7 Completed

This chapter has traced the development of Euro-American modernism within the broader context of what is now called globalism. There was a time when the term modern was synonymous with Western Europe (centered in cities like Paris or Berlin), then later the United States (centered in New York City).

Art history traditionally traced the path of modern art as a break with the classical past, and as an attempt to picture the industrialized modernity of these centers. Art outside these centers was relegated to a secondary status, unenlightened, unmodern, and primitive, but useful as part of a new visual vocabulary, harnessed by Western artists as they sought out new modes of representation. All combined, this chapter helps to re-frame this relationship without re-asserting the implicit hierarchy between what cultural theorist Stuart Hall called “The West and the Rest.”

Key questions to guide your reading

How was the development of modern art impacted by encounters with colonial cultures?

Does cultural appropriation differ from artistic influence?

How do Primitivism and Indigenism overlap?

Jump down to Terms to KnowHow was the development of modern art impacted by encounters with colonial cultures?

Does cultural appropriation differ from artistic influence?

How do Primitivism and Indigenism overlap?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

Learn more

Frances S. Connelly, The Sleep of Reason : Primitivism in Modern European Art and Aesthetics, 1725–1907 (University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999).

Thomas Folland, “Readymade Primitivism: Marcel Duchamp, Dada, and African Art,” Art History: Journal of the Association of Art Historians, vol 43:4 (September 2020): pp. 802–26.

Michele Greet, Beyond National Identity: Pictorial Indigenism as Modernist Strategy in Andean Art 1920–1960 (The Pennsylvania University Press, 2009).

Stuart Hall, “The West and the Rest,” (1992) in Essential Essays, Vol 2, ed., David Morley (Duke University Press, 2019).

Elizabeth Harney and Ruth B. Phillips, Mapping Modernisms: Art, Indigeneity, Colonialism (Duke University Press Books, 2019).

Elizabeth Hutchinson, The Indian Craze: Primitivism, Modernism, and Transculturation in American Art, 1890–1915 (Duke University Press, 2009).

Harper Montgomery, “Carlos Mérida and the Mobility of Modernism: A Mayan Cosmopolitan Moves to Mexico City.” The Art Bulletin 98, no. 4 (2016): pp. 488–509.

William Rubin et al., eds., “Primitivism” in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1984).

Sascha T. Scott, A Strange Mixture: The Art and Politics of Painting Pueblo Indians (University of Oklahoma Press, 2015).