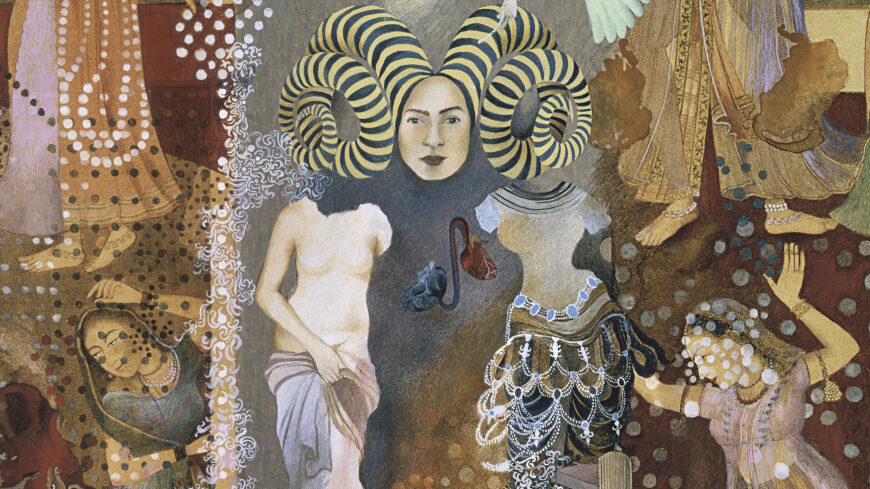

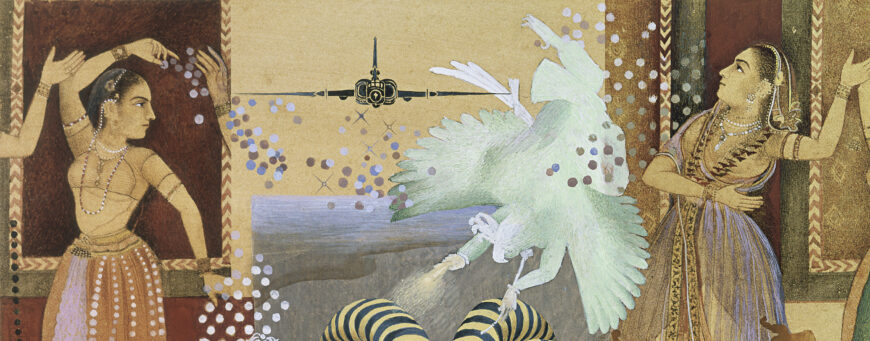

Red and blue organs (detail), Shahzia Sikander, Pleasure Pillars, 2001, vegetable color, dry pigment, watercolor, and tea on wasli paper, 43.2 x 30.5 cm (Collection of Amita and Purnendu Chatterjee) © Shahzia Sikander, courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London

What appears as two connected organs—one red and one blue—draws us into the central space of the painting, between two headless bodies, as we meet the gaze of a woman with large horns. Above this scene, a large mythological creature is juxtaposed with a monochromatic black jet in the sky, while dancers perform all around them. What do these images and symbols mean in this small watercolor painting from 2001? Why are they brought together in this way? How can we understand what the artist, Shahzia Sikander, is trying to say in this visually complex work? What forms of pleasure could Pleasure Pillars refer to? Do the pillars represent a physical or perhaps a magical space in which this scene is taking place?

Shahzia Sikander, Pleasure Pillars, 2001, vegetable color, dry pigment, watercolor, and tea on wasli paper, 43.2 x 30.5 cm (Collection of Amita and Purnendu Chatterjee) © Shahzia Sikander, courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London

In Pleasure Pillars, Sikander uses materials and techniques of traditional Indo-Persian miniature painting, an artistic practice that draws on traditions from what is today Pakistan, India, and Iran (historically known as Persia). Sikander combines aspects of Indo-Persian miniature painting with content from the history of both Western and Asian art and contemporary references to invite us to look more closely and deeply at the world around us.

Attributed to Bhola, Shah Jahan Honoring Prince Aurangzeb at his Wedding, c. 1640–50, opaque watercolor including metallic paints, 33.7 x 23.5 cm (Royal Collection Trust, London)

Indo-Persian miniature painting

The term “miniature” is fitting since these paintings are typically no larger than a standard piece of modern printer paper and include meticulously painted details. Widely popular by the 15th and 16th centuries, Indo-Persian miniature paintings, such as those commissioned by Mughal rulers, like the one attributed to Bhola, titled Shah Jahan Honoring Prince Aurangzeb at his Wedding, traditionally depicted a range of subjects that appealed to the ruling elite, such as courtly scenes including royal audiences and other state ceremonies, illustrated poetries, histories, myths, and hunting scenes. Rulers of South Asia from the 16th to 19th centuries, the Mughals commissioned artists to make miniature paintings that reflected their cosmopolitan tastes, drawing on the visual traditions of Persia, South Asia, and also of Europe.

Historically, this art form was exclusively practiced by men who often inherited a workshop and trained directly with their fathers. Common materials and techniques of Indo-Persian miniature painting included hand-prepared wasli paper, made by layering thin sheets of paper together with flour paste and then burnishing (rubbing) with a hard, smooth object across the surface of the paper. Often, a conch-shell or agate (a type of gemstone) was used to burnish the paper, sealing in fibers to generate a satin-like finish. [1] The paper would then be dyed with tea before layers of watercolor paint were applied and the final details made with a squirrel-hair brush, in a process known as pardakht. [2]

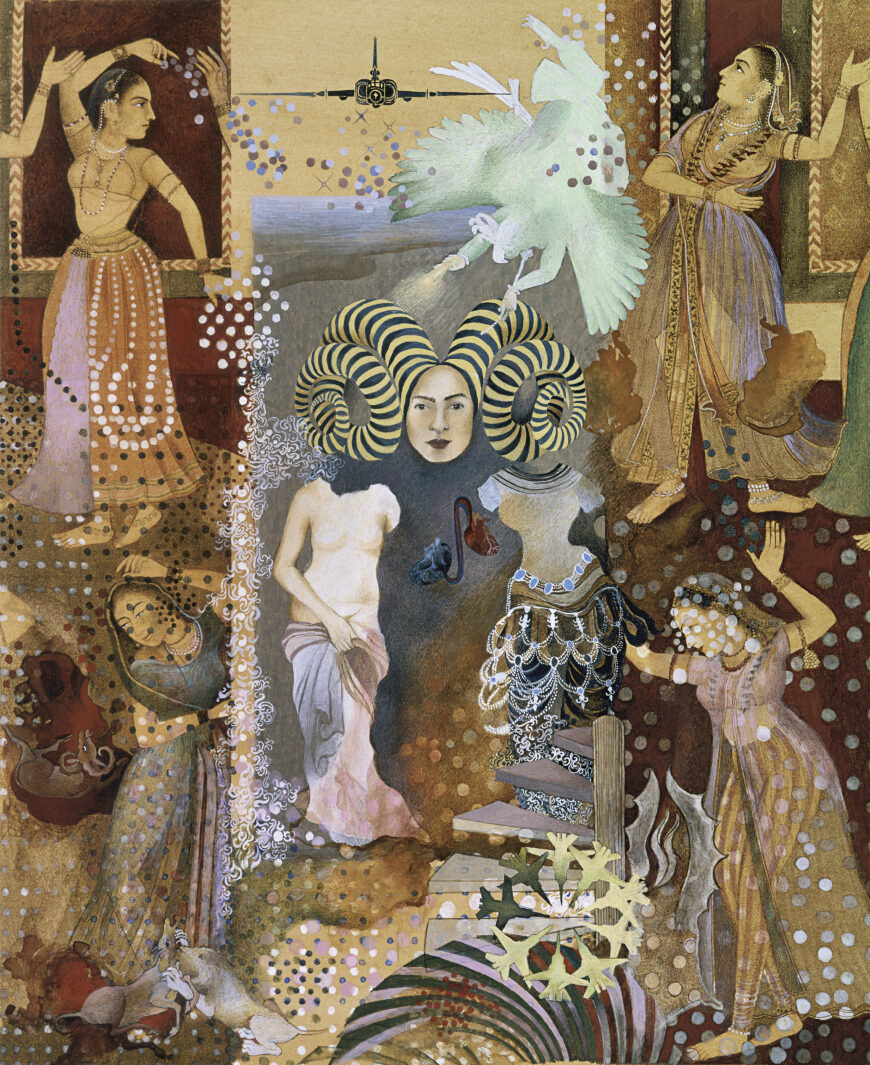

Figure covered in white and gray dots (detail), Shahzia Sikander, Pleasure Pillars, 2001, vegetable color, dry pigment, watercolor, and tea on wasli paper, 43.2 x 30.5 cm (Collection of Amita and Purnendu Chatterjee) © Shahzia Sikander, courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London

Shahzia Sikander and Neo-miniature painting

Born in 1969 in Pakistan, Shahzia Sikander first studied Indo-Persian miniature painting at the National College of Art in Lahore. There she began to use this traditional painting format as a catalyst for exploring contemporary subjects from the perspective of a South Asian woman. Later, in the mid-1990s while attending the Rhode Island School of Design in the United States, Sikander began to explore her new diasporan experiences in her art. In doing so, Sikander introduced the painted dots that can be seen throughout Pleasure Pillars with subjects—both past and present, South Asian and Western—generating a style known as Neo-miniature Painting (or “New” miniature painting).

South Asian female agency

Sikander made her own wasli paper for Pleasure Pillars and used a squirrel-hair brush to create a visually layered composition that speaks to her perspective as a Pakistani-born Muslim woman living in the United States in the 21st century. Sikander places a self-portrait with striped horns in the center. This figure’s eyes meet ours with striking confidence. This confidence reflects her ability to create a complex work of art that both celebrates the female body and feminine agency, while “speaking back” to the dominance of “the West” and the European tradition in art history.

Self-portrait with striped horns (detail), Shahzia Sikander, Pleasure Pillars, 2001, vegetable color, dry pigment, watercolor, and tea on wasli paper, 43.2 x 30.5 cm (Collection of Amita and Purnendu Chatterjee) © Shahzia Sikander, courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London

This horned head floats between two headless representations of the female body—the semi-nude body on the left seems to be a reference to ancient classical statues like the Venus de Milo, while the body on the right is reminiscent of South and Southeast Asian depictions of dancers. [3] Through these examples, Sikander illustrates longstanding traditions of the objectification of women’s bodies in both Western and South Asian art history. However, through this pairing, Sikander also celebrates her presence as a female artist who can create art that draws on both Asian and Western traditions of art making.

In this work of diasporic art, the headless bodies may represent states of dislocation—such as the dislocation someone living away from their homeland may feel, but Sikander explains that her use of headless female figures also represents the symbolic beheading and erasure of traditional female divinities in contemporary Pakistani culture. This act of violence—Sikander’s severing of the head from the body—points to how, for centuries, the peoples of what is today Pakistan revered female divinities prior to the arrival of patriarchal religions such as Islam (which discarded female deities). [4] And perhaps, through the juxtaposition of these two headless female bodies, Sikander introduces a connection between “the West” and Asia, pointing to how female divinities like Venus were also revered in “the West,” and that this changed too, with the introduction of Christianity.

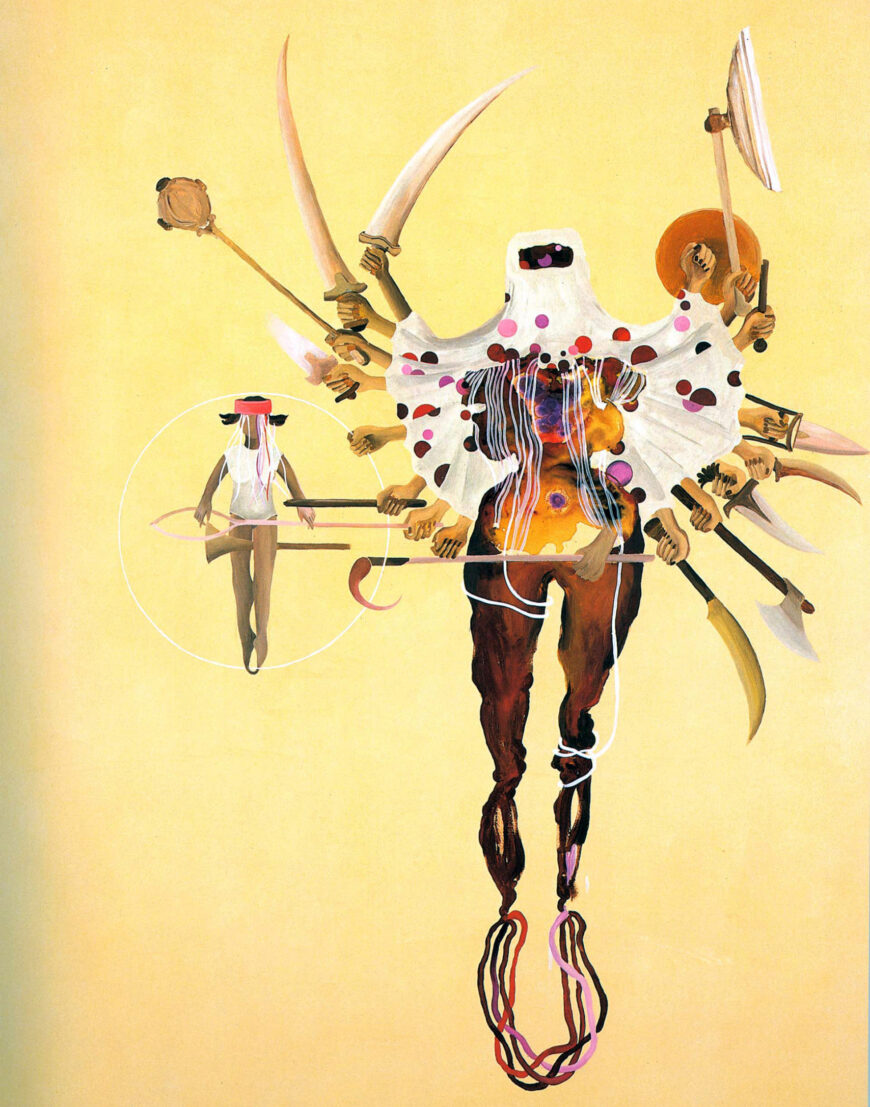

Avatar (detail), Shahzia Sikander, Fleshy Weapons, 1997, acrylic, dry pigment, watercolor and tea wash on linen, 243.8 x 167.6 cm © Shahzia Sikander

Furthermore, Sikander often represents headless beings in her work, calling them “avatars,” many of which appear to resemble the Hindu goddess Durga with multiple arms holding weapons. However, in her 1997 work Fleshy Weapons and elsewhere, Sikander replaces the feet of the goddess with interlinked roots—roots that are not planted into the ground to draw up nourishment, but that are interconnected and self-nourishing. Sikander explains:

The beheaded feminine forms with interlinked roots of my lexicon were about my observing as a young artist the lack of female representation in the art world and the misogyny present toward women in almost all spheres of work and life. Shahzia Sikander, 2019 [5]

In Pleasure Pillars, this goddess takes on a new form, as Sikander transforms this image of the warrior Durga, abstracting the female body into a radiating circle of hummingbird-jets, an omnipresent goddess and an expression of feminine agency, located in the bottom right of the compositional space. Moreover, women dance across the top and the bottom of the watercolor, with additional arms and legs included in the composition, indicating multiple figures. These dancing women do not occupy a common ground line, but float through the composition in a manner that recalls Southeast Asian and South Asian examples of apsaras and gopis. In Pleasure Pillars, Sikander draws on the rich visual traditions of Asia—from different stages of history and different religious traditions—to compose collective gatherings of women, who appear throughout Sikander’s body of work, and through their repetition, stake a claim within contemporary global art history.

Dancing women (detail), Shahzia Sikander, Pleasure Pillars, 2001, vegetable color, dry pigment, watercolor, and tea on wasli paper, 43.2 x 30.5 cm (Collection of Amita and Purnendu Chatterjee) © Shahzia Sikander, courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London

Obscurity and visibility: insights on contemporary global culture

Through Neo-miniature painting, Sikander introduces formal characteristics in a manner uncommon to traditional miniature painting to explore acts of labor, violence, and erasure. In Pleasure Pillars, Sikander employs dots of various sizes, saturation, and colors to cover areas across the sheet of paper. [6] These dots obscure content, calling attention to what is exposed and what is hidden, or hard to see through the diaphanous layers introduced by Sikander within the compositional space. Dots in Sikander’s art practice reference Islamic aesthetics, as circles and squares are often the basis for the intricate geometric patterns characteristic of Islamic art.

Dots might reference Islamic aesthetics or bullet holes (detail), Shahzia Sikander, Pleasure Pillars, 2001, vegetable color, dry pigment, watercolor, and tea on wasli paper, 43.2 x 30.5 cm (Collection of Amita and Purnendu Chatterjee) © Shahzia Sikander, courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London

However, the artist also uses repeated circles because of their resemblance to bullet holes—Sikander began exploring gun violence in America and gun culture in the South as a theme in her art practices while living in Texas as a Fellow at the Glassell School of Art. [7] Over the course of three years, she spent time working at Project Row Houses in Houston’s Third Ward exploring the theme of gun violence. [8] Therefore, in Pleasure Pillars, Sikander’s dots may resemble buoyant raindrops, or luxurious pearls cascading throughout the compositional space recalling the opulence of actual pearls glued to the surface of miniature paintings, bullets, or even bombs being dropped from aircraft. [9] To the right of the jet at the top of the painting, a much larger composite creature (part human and part bird) appears ghost-like or angelic. What is this creature’s role within this space? Does the addition of the jet to Pleasure Pillars after the September 11, 2001, attacks on the World Trade Center further augment its meaning? [10] Is the jet meant to signify potential destruction? And how have invasions by force, such as colonialism, impacted access to cultural knowledge and the preservation of cultural heritage in Asia?

Through the juxtaposition of various techniques and subject matter in Pleasure Pillars, Shahzia Sikander models acts of transformation—of the self, of a community, of cultures, and of history—to invite opportunities for complex readings that enable one to look more closely and critically at the world around them.