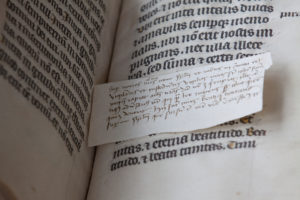

Tiny slip of parchment, likely made from scrap material, inserted to add notes to the text, Schedula, Leiden, University Library, BPL MS 139, 15th century (photo: Giulio Menna)

Leftovers (schedulae)

When the scribe cut sheets out of the animal hide, he would normally use the best part of the skin—what may be called the “prime cut.” This meant staying clear of the very edge of the skin because these areas were very thin and translucent, and deemed unsuitable for books. The scribe, therefore, cut a rim of parchment from the edge of the skin. It usually came off in tiny bits and pieces, which he called schedulae—strips. These odds and ends were thrown in the bin. Sometimes they were taken out to be used as scraps, for example, for taking notes in the classroom or for smaller pages inserted into existing manuscripts. These tiny pages supplemented the text or added notes, like our yellow sticky notes today.

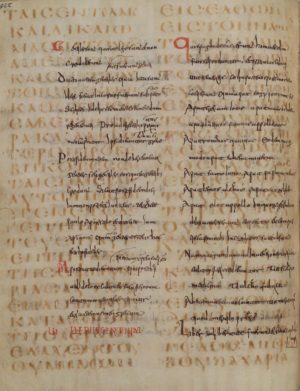

An example of a palimpsest, Codex Guelferbytanus A, Wolfenbüttel, 6th century (lower text) (Herzog August Bibliothek, MS Lc 1, 6-13, folio 92 verso)

Layers (palimpsest)

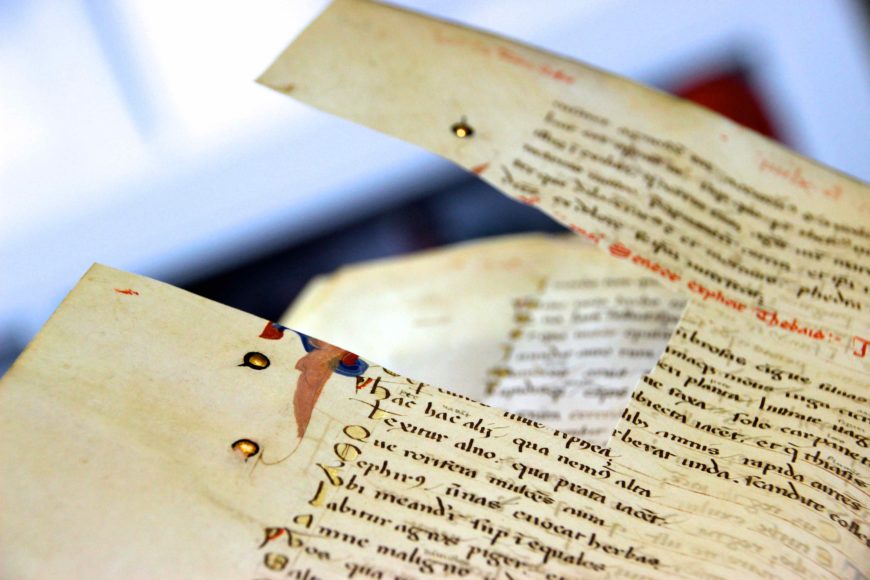

What to do when you run out of parchment as a medieval scribe? You can look around for something else to write on, such as left-over parchment strips in the bin (schedulae), or use paper, if it is available. Alternatively, you can take a book that is no longer used from your monastery’s library and scrape the text off its pages. You then simply apply text of your own. Such recycling resulted in a “palimpsest,” which holds a removed “lower text” and a newer “upper text.” The ink of the reapplied text often does not stick to the page very well, as is clearly seen in the image. Moreover, the older reading often shines through. Especially important are palimpsests from the earlier Middle Ages, because underneath this old text an even older work is buried, like a stowaway. With digital photography the lower text can sometimes be made visible again, which makes studying these books like digging for treasure.

Scribe purchasing parchment, Hamburg Bible, 1255 (Copenhagen, Royal Library, MS 4, 2o, folio 183 verso)

Post-production

Bad skin may also tell us something about the individuals who owned, read, and stored manuscripts. The presence of holes and rips may, for example, indicate the cost of the materials. Studies suggest that parchment was sold in four different grades, which implies that sheets with and without visible deficiencies may have been sold at different rates. If this was indeed the case, an abundance of elongated holes in a manuscript may just point at an attempt to economize on the cost of the writing support. In other words, bad skin may have come at a good price.

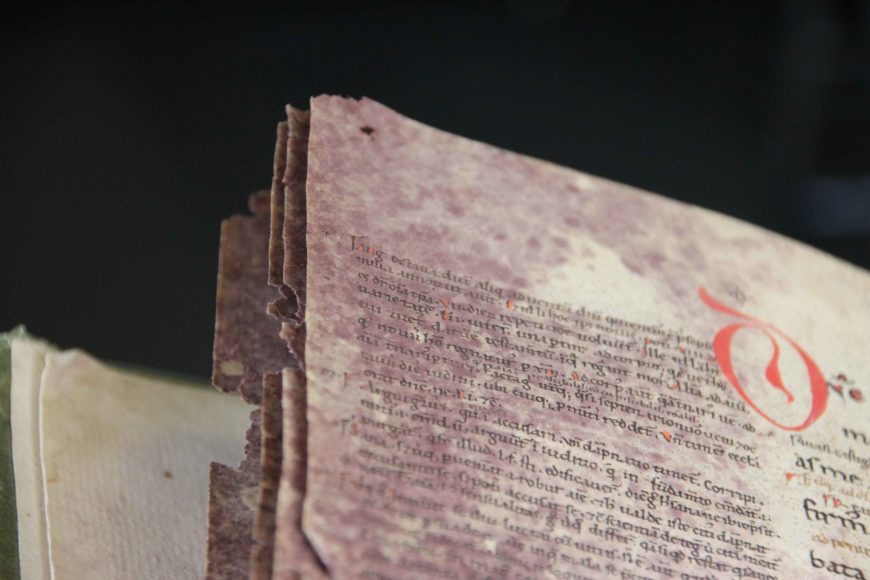

Mold has attacked these pages and turned them purple, in an almost beautiful way. Leiden, University Library, BPL MS 2896, 12th century (photo: Erik Kwakkel)

Parchment provides other information about readers as well, for example, that he or she stored a book in an unsuitable location. Damp places, for one, would leave a mark on the manuscript’s skin, as is clearly seen in a manuscript I sometimes call the “Moldy Psalter”—for moldy it is.

On nearly every page, the top corner shows a purple rash from the mold that once attacked the skin. It is currently safe and the mold is gone, but the purple stains show just how dangerously close the book came to destruction—some corners have actually been eaten away. Similarly, if a book was stored without the proper pressure produced by a closed binding, for example, because the clasp was missing, the parchment would buckle and produce “waves” on the page.

Apart from such attacks by mother nature, a manuscript could also be scarred for life by the hand of men—those evil users of books. Well-known are cases where scribes and readers erased text with a knife, either because the reading was wrong or because they disagreed with it. However, in the wrong hands, a knife could easily have a more severe impact on the book’s skin. All those shiny letters on the medieval page were too much for some beholders. The individual that gazed at the golden letters in the manuscript shown below used his knife to remove some of them.

The golden letters in this manuscript were stolen by a thief in the past, who cut them out with a knife. Leiden, University Library, BPL MS 59, 14th century (photo: Erik Kwakkel)

While the velvety softness of perfect skin can be quite appealing to handle, getting to know imperfect parchment is ultimately more interesting and rewarding. Damage is telling, and it may shed light on such things as the attitude of scribes (who did not necessarily mind holes on the page), the manner in which a book was stored by its owner (with a missing clasp or in a wet environment), and even the state of mind of those looking at it (“Must cut out golden letters!”). As a book historian, it feels good to work with bad skin.