Suchitra Mattai, Exodus, 2019, vintage saris from India, Sharjah, artist’s Indo-Guyanese family and rope net, 15 x 40 ft (Collection of the Momentary, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art)

When artist Suchitra Mattai received her artwork Imperfect Isometry back from its outdoor showing at the Sharjah Biennial, she noticed that the materials looked quite different. The constant sun on the installation of woven saris—traditional Indian women’s garments—had lightened the previously vivid colors of the silk, cotton, and polyester. These same saris made their way into Mattai’s later work Exodus, a massive wall hanging in the collection of the Momentary, a contemporary art space of the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Arkansas. In Exodus, the sun-bleached saris are embedded in a landscape of fabric that dominates an entire wall.

Suchitra Mattai, Imperfect Isometry, 2019, videos of border walls (Jerusalem/Palestine, U.S./Mexico) and prison wall, vintage sari tapestry, chalk drawing, spinning found Kalba merry-go-round; Sharjah Biennial 14 (2019)

The title Exodus, although well-known as one of the books of the Jewish Torah and the Christian Bible, is more broadly defined as a departure or emigration (permanently leaving one’s home), and fittingly relates the journey of the saris from their origins around the world (she sources the saris from her family, friends, and women of the South Asian diaspora), to the installation at the Sharjah Biennial, to the museum in Arkansas. The saris can be seen as surrogates for the women who wore them: South Asian women now living in diaspora (the dispersion of people from their original homeland) throughout the world. But the title also reflects a more personal journey of the artist and her family that began decades ago in the South American country of Guyana.

Roots and routes

Guyana sits on the northern coast of South America on the Atlantic Ocean and near the Caribbean Sea. Originally home to several Indigenous groups, Guyana became a site of ongoing and alternating colonial exploitation beginning with the Dutch in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. The Dutch enslaved Africans and brought them to the region to work in various agricultural ventures. Later, the British would take over as imperial rulers, likewise engaging in slavery and forcing the migration of thousands of Africans to Guyana, then known as Guiana. By the 1830s, slavery was officially abolished in the colonies of the British Empire, and so the British needed a new labor force to work the sugar (and later, rice) plantations. At the time, the largest British colony was India, and so Indians were offered work in Guiana for five years, at which point the indentured laborers could choose to return home with a bit of money or keep a small plot of land in Guiana. The work was still very much exploitative, as the laborers were often forced to work 14–16 hours per day for very little in return.

Mattai’s grandparents arrived in Guiana from India when it was still a British colony in the 1930s, her grandfather as an indentured laborer. Following his five-year period of service, Mattai’s grandfather returned to India to a difficult environment—a system immersed in caste divisions and unwelcome to Mattai’s family. They traveled back to South America, dangerously navigating the Atlantic before joining the Indian community which had settled in the Caribbean region.

Suchitra Mattai, born in Guyana (which declared Independence from the United Kingdom in 1966), has likewise journeyed and lived around the globe. At three years old, her family immigrated to Canada. As a graduate student at the University of Pennsylvania, Mattai spent extended periods of time in India for her research toward an MA in South Asian art. Later in life, Mattai and her family moved to Europe, and then back to the United States. The artist’s work often invokes notions of displacement and migration rooted in these experiences, and Exodus is no exception.

Suchitra Mattai, Exodus (detail), 2019, vintage saris from India, Sharjah, artist’s Indo-Guyanese family and rope net, 15 x 40 ft (Collection of the Momentary, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art)

Identity and diaspora

Looking at Exodus closely, one finds variations in fabric, color, pattern, and design; from afar, faint outlines of long, horizontal shapes seem to emerge. Are these mountain ranges? Clouds? A horizon? The faded saris—woven between the brightly-colored saris not exposed to the sun—work like brushstrokes across the image, creating undulating lines and echoing the peaks and valleys of the hanging itself. Looking across the image from either side, these bumps and shadows mimic a landscape, as though a three-dimensional topographic map was placed vertically on a wall. Yet the reference to place is not entirely clear.

Mattai has described disparate landscapes as faded memories as she grapples with notions of identity, displacement, and diaspora. Since she sources the saris from her family, friends, and women of the South Asian diaspora around the world, she notes that these fabrics often still retain smells of curry or perfume—the identities of the women coming together in a powerful work:

The threads that carry into my current work are my desire to communicate something about the ‘global,’ what it is to be an immigrant, and what it feels like to be displaced and disoriented. [1]

Materiality and migration

Saris appear in several of Mattai’s work. In her Life-Line installation, a dramatically tipped wooden boat hangs almost vertically from the ceiling, saris pour overboard as if a liquid. The instability of the situation recalls Mattai’s ancestors’ dangerous trans-Atlantic journeys. The water-like appearance of the saris as they spill over into a whirlpool on the ground recalls a place or setting, perhaps Guyana, whose name means “land of many waters” in an Amerindian language (sources do not agree as to which specific one). The “life-line” of the title seems to be those very saris that connect the boat to the solid ground, a circle developing on the floor. The circle is not precarious, unlike the boat from which it emerges. It is solid, growing, and rooted, perhaps a metaphor for the Indian community of Guyana and the connections between the South Asian diaspora more broadly.

Mattai’s constant exploration of materials likewise brings together several seemingly disparate parts to complete a whole. She is trained as a painter, but her art frequently employs found weavings and needlepoints so often relegated to “folk art,” or a lower “handicraft” status—work generally created by women. By incorporating these older textiles into her art, Mattai reclaims agency for these artists of earlier ages, saying:

My primary pursuit is to give voice to people whose voices were once quieted. [2]

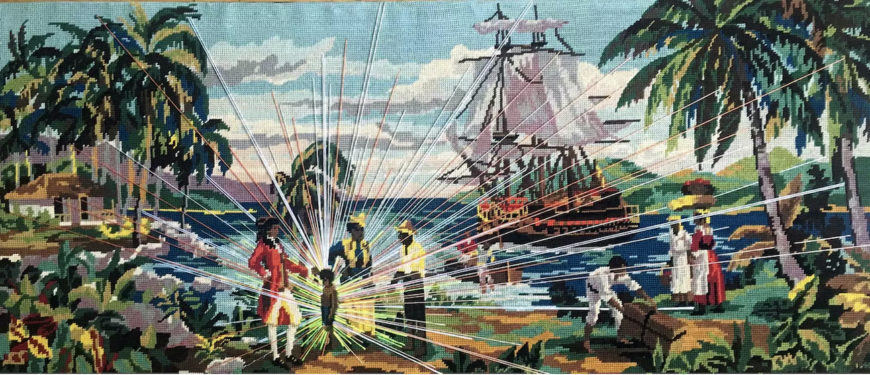

In addition to reclaiming various materials as fine art, Mattai reimagines scenes (and by extension, history) dominated by colonial narratives. In Castaway, Mattai begins with a found needlepoint depicting an island or coastal scene with a British ship and soldier flanking a small figure—presumably an Indigenous or Indian (South Asian) child attempting to get on the boat and perhaps the namesake for the title—at the center of the work. Mattai isolates and highlights the child by incorporating starburst-like lines around the figure. She reclaims the innocence and humanity of the child and shifts the historical narrative that so often overlooks these lives, saying:

Re-writing this colonial history contributes to contemporary dialogue by making visible the struggles and perseverance of those who lived it. [3]

A monumental reunion

Suchitra Mattai, Exodus, 2019, vintage saris from India, Sharjah, artist’s Indo-Guyanese family and rope net, 15 x 40 ft (Collection of the Momentary, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art)

Exodus continues this discussion. Although there are no figures in the massive tapestry, the presence of the South Asian diaspora is manifest through the almost 200 globally sourced saris—it is a monumental reunion. Exodus is quite personal for the artist, clearly drawing from Mattai’s family history and experiences. But its underlying questioning of dominant historical narratives—particularly as they relate to migration and identity—is universal. As faded lines in Exodus slowly emerge, a sense of place—however tenuous—becomes apparent.