View of the main temple on the highest terrace seen from the west, Sukuh, Java, 15th century (photo: Panggah Ardiyansyah)

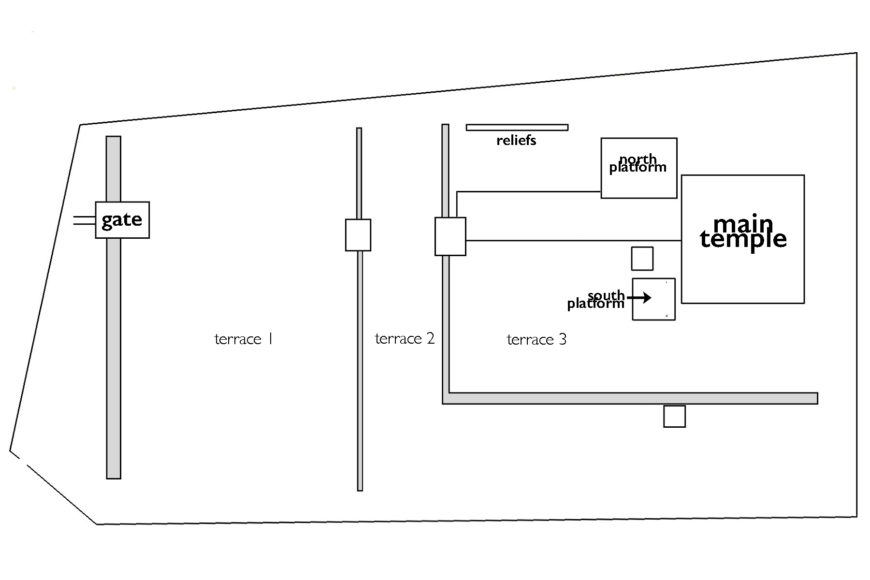

Although the Hindu site known as Sukuh on the western slope of Mount Lawu (in central Java, Indonesia) is less colossal than the more well-known Borobudur (the world’s largest Buddhist temple, also in Indonesia)—it is just as captivating. The main temple, with its pyramid-like appearance, is unlike any other on the island. It is located on the highest of three terraces, and is approachable by walking through a series of narrow gates and stairway.

These three ascending terraces represent different levels of sacrality—with the highest being the most sacred. This structural arrangement, as well as the temple’s setting (close to the peaks of Mount Lawu), comes from a belief that revered ancestor spirits and Hindu gods reside in higher ground (like a mountaintop).

Linga, Sukuh (photo: Ministry of Culture of Indonesia)

Various reliefs and statues distributed across the three elevated terraces give clues to how the temple would have functioned as a Hindu religious sanctuary. This imagery includes the Hindu hero Bhima and the mythical bird Garuda (more well-known as the vehicle of the god Vishnu). Another Hindu deity, Shiva, is represented by a massive linga (not in situ) that is thought to have originally been located on the top of the main structure. Close examination of the architectural ornaments and sculptures of Sukuh also reveals that male and female genitals symbols of life creation, are the predominant visual theme that unites its sculptural program. Male figures are often depicted with a visibly erect phallus, while an image of a vulva appears on the floor of the roofed gate in the first terrace. Aside from Sukuh, the only temple where we can find this type of visual imagery is at nearby Cetho, another Hindu temple from the same time period, also located on the slope of Lawu. In past scholarship, the imagery was often presented as a crude creation by less-skilled local artists, signaling the decline of Hindu Javanese artistic tradition. Recent studies have been more appreciative of the genital imagery in Sukuh and Cetho as portraying different sectarian affiliations.

View of the main temple on the highest terrace seen from the west, Sukuh, Java, 15th century (photo: Panggah Ardiyansyah)

Various inscriptions and chronograms carved into the temple architecture tell us that Sukuh is dated to the first half of the 15th century. This dating places the temple under the political influence of the already-waning Majapahit Kingdom, centered in Trowulan, east Java (around 84 miles to the east of Sukuh). Whether Sukuh was a state temple directly under the king’s patronage is debatable due to its distance to the center of power and its location in the mountains. With Hinduism first appearing on the island of Java in the 5th century, Sukuh exemplifies the last stage of Hindu architectural development before the majority of population started to embrace Islam in the 16th century.

A mixture of spiritual elements: ancestral worship, cosmic creation, and Hinduism

Located near the top of Mount Lawu, Sukuh is part of a wider ancient landscape of the area, which consists of step pyramid structures (locally known as punden berundak), sacred springs, and other Hindu temples. It is not a coincidence that the construction of Sukuh combined spiritual elements from these preexisting architectural and natural forms. The structure of punden berundak, which existed since prehistoric Java, was adopted in Sukuh to represent Mount Mahameru of Hindu mythology— believed to be the home of the god Shiva.

The Sukuh compound consists of three ascending terraces, facing west with the mountain at its back. This terraced construction is reminiscent of the stepped pyramids (punden berundak) that are often seen as part of Austronesian-speaking communities that have populated maritime Southeast Asia since the first millennium B.C.E. Some are located in Java, such as Gunung Padang in the western part of the island. Punden berundak are usually formed by earth and stone constructed terraces that rise from the ground up, and are intended to represent the mountain home of ancestral spirits.

Standing on the third platform, looking towards the entrance

In Sukuh, the highest terrace is occupied by a group of structures. These include the main pyramid temple, a smaller trapezium temple fully covered with reliefs, two elevated platforms, and two statues of Garuda. The main temple is interestingly devoid of relief. It has a stairway leading visitors to the temple’s summit where a massive linga was originally installed. Two guardian statues dwell in the second terrace, in front of the stairway leading to the third, while a few relief blocks are presently arranged on the left of the first terrace.

The roofed gate seen from behind, with a kala face, Sukuh, Java,15th century (photo: Panggah Ardiyansyah)

To reach the first terrace, one needs to climb narrow and steep steps up to a roofed gate. It is the only gate found in Sukuh that is adorned with kala faces above its doorway. Both sides of the gate’s roof are covered with sculptures of Garuda spreading his wings (below), catching nagas (serpents) with their claws.

The bird Garuda, whose both wings open but face is already damaged, claws two nagas of which bodies were wrapped around each other, Sukuh, Java, 15th century (photo: Panggah Ardiyansyah).

The phallic linga is erected on a yoni as its foundation, c. 8th century (Kailasa Museum, Wonosobo; photo: Panggah Ardiyansyah)

These sculptures’ refer to the Hindu story of the feud between the Garuda and the nagas. To release his mother from the nagas’ enslavement, Garuda was ordered to steal amrita (the elixir of life) and hand it to the nagas. With the help of Vishnu, Garuda deceived the nagas and freed his mother. In return for this assistance, Garuda agreed to become Vishnu’s vehicle.

On the floor of the gate’s passageway, vertically aligned depictions of male and female genitalia (phallus at the bottom and vulva at the top) can be seen as an allusion to the theme of life creation. The pairing calls to mind the Shivaistic linga and yoni symbolizing the union of male and female principles as the origin of all existence. While linga and yoni are commonly found inside the main chamber of Javanese-Hindu temples, the pairing of phallus and vulva in Sukuh are remarkable since they do not occur in any other temples. Some scholars have argued that the existence of these genital references betrays the tantric teachings used to construct Sukuh.

The mythical bird Garuda carrying natural produce, seen from the front and back, Sukuh, Java, 15th century (photo: Panggah Ardiyansyah)

Approaching the main pyramid temple in the highest terrace, one is greeted by two side-by-side life-sized statues of Garuda on the right—each is depicted in the form of a human body with wings and claws. While the figure of Garuda is not uncommon in Java’s Hindu structures, his depiction with a human body is unique to Sukuh. The second figure is particularly interesting since Garuda carries loads of natural produce hanging from a wooden stick carried over the shoulder. Some can be identified as local products, such as coconut, eggplant, banana, mango, and pineapple. Might we assume that these are the kind of foods eaten by the mountain sage in Sukuh? Unfortunately the two Garudas’ original positions within the compound are not known, making it difficult to interpret the figures. Scholars have assumed that Sukuh was built by the sages as a reclusive sanctuary of religious worship as well as of spiritual contemplation.

The medallion in the southern platform, where the standing high crowned figure is seen holding double trisulas in both hands (photo: Panggah Ardiyansyah)

There are two elevated platforms in front of the main temple. The southern one is fitted with a pillar in its southeast corner, and carved with a medallion depicting a god (possibly Shiva) holding a double trisula in both hands. A small linga is located at the back center of the southern platform. It is not known how this platform originally functioned.

The relief panel with inscription telling about the water basin, Sukuh, Java, 15th century (photo: Panggah Ardiyansyah)

The northern platform seems to be bordered with a wall sculpted with reliefs (the south and west sides are no longer extant). It is possible that the walled platform was used to collect the sacred amrita when rain water was purified by the temple’s symbolic power. A water channel installed above the platform seems to support this interpretation. The Old Javanese inscription in a broken-up relief panel attests to the construction of a water basin that can be read as padamel rikang bukutirta sunya 1361 Saka (it reads, “this panel is installed to the wall of a water basin of a hermitage 1439 C.E.”). In this panel, the figure in the center identified as the Hindu hero Bhima can be seen stabbing and lifting an enemy using his long thumb nail.

A monolithic linga presently at the National Museum of Indonesia in Jakarta (shown earlier), almost two meters in height, is said to have come from Sukuh. While many lingas in Java are depicted in smooth round pillars with rounded tops, the linga from Sukuh has the glans carved at the top, directly above four rounded scrotums, with a square base. If we assume that this massive linga was originally placed at the top of the main pyramid temple, we might consider the structure of the main temple as a representation of a yoni, though a gigantic one. As often observed in Hindu ritual, water is poured on to a linga to purify the earth below. The similar symbolic process could be applied to the Sukuh architecture. When the rain falls onto the main structure, the water would become sacred and in turn would purify the land, with some of this sacred water collected in the northern platform.

Commemorating the constructions

Chronograms can be found in abundance in Sukuh. While foundational inscriptions are common in Southeast Asian temples, the chronogram is uniquely Javanese. This art of dating represents a creative way to memorize dates by presenting a year numerally encoded in a sequence of textual and pictorial symbols. [1]

The pictorial chronogram on the left wing of the gate, Sukuh, Java, 15th century (photo: Panggah Ardiyansyah)

Examples of pictorial chronograms are sculpted in the gate leading to the first terrace. The chronograms are located on the right and left wings of the gate. Based on the interpretations of these chronograms, the gate at Sukuh was constructed in the year 1440 C.E. The figure in the left wing of the gate can be interpreted as gapura buta aban wong (gate monster eats human). This is visualized by the smaller sized human being held up by the gate’s monster and about to be eaten. In the semantic system of Javanese language, the word gapura refers to the numeral 9, buta refers to 5, aban refers to 3, and wong refers to 1. To get the commemorated year numeral, this reference should be read backward, which gives us the year 1359 in the Saka calendar (corresponds to 1440 C.E.).

The pictorial chronogram on the right wing of the gate, Sukuh, Java, 15th century (photo: Panggah Ardiyansyah)

Meanwhile, the sculpted figure in the right wing of the gate should be read as gapura bhuta nahut butut (gate monster eats tail), which is visualized by the gate’s monster eating the snake’s tail. Gapura refers to 9, bhuta refers to 5, nahut refers to 3, and butut refers to 1. Here we can see that, while the right and left wings have different sculptural figures, they correspond to the same year numeral, which is 1359 in the Saka calendar. [2]

The expression in commemorating a sacred foundation using year numerals and chronograms signifies a later development of Hindu artistic tradition in Java, which started to appear in the 10th century. This commemorating practice is not limited only to temples, but can be found on sacred natural rock formations, bathing places, and even ritual instruments such as water jugs and offering tables. It came to its peak in the Majapahit era, with Sukuh appearing to be the apogee. A well-known example closer to the center of Majapahit in east Java is the 14th/15th-century Penataran Temple. Year numeral inscriptions in varying structures and sculptures at Penataran indicate that they were constructed by different Majapahit kings. Sukuh, on the other hand, is striking because the year numerals and chronograms can be found in every principal structure and sculpture on the site commemorating dates within a shorter span of time. While it is not uncommon for a premodern Javanese manuscript to employ chronograms and year numerals simultaneously, it is exceptional to find this practice in a temple construction.

Purification and liberation of the soul

A cult to worship Bhima (Hindu hero and the second brother of the Pandavas seems to have appeared in the late Majapahit period, primarily in mountain sanctuaries like Sukuh. There is an assumption that his heroic quality as a savior might have rendered him one of the ancestors of Majapahit. [3] Bhima features prominently in Sukuh where he appears both in relief and as a larger than life statue (such as one below). The “blacksmith panel” seems to occupy a special place for today’s local community and the scholarly world alike. The panel depicts three figures producing metal tools. On the left, a squatting figure, identified as Bhima, is forging a weapon. In the center, an elephant-headed figure, likely Ganesha, stands on one foot and holds a dog with his right hand. Another figure is operating the traditional double-piston bellows on the far right to control the fire.

From several inscriptions found in Java before the 15th century, we understand that blacksmiths were already acknowledged as a specialized profession. Art historian Stanley J. O’Connor has argued that the panel illustrates iron working as a metaphor for spiritual transmutation to liberate the soul through ancestor worship and ritual. [4] In this regard, the process orchestrated by the blacksmith to forge iron into a desirable shape constitutes the release of the soul from being trapped in a bodily form to the otherworld. Early 19th-century villagers near Sukuh supposedly came to make offerings to the “blacksmith panel” who regarded the depicted figures as ancestors for Javanese blacksmiths. This practice is evidence of the enduring appeal embodied in the relief for local society at least since the 15th century.

The relief narrating the story from Bhima Svarga, Sukuh, Java, 15th century (photo: Panggah Ardiyansyah)

The statue of Bhima at Dalem Hardjanegaran, from Sukuh, Java, 15th century (photo: Panggah Ardiyansyah)

A set of reliefs depicting the story of Bhima Svarga, carved in the smaller trapezium temple in front of the main pyramid temple, tells a similar theme of soul deliverance. In this story, Bhima acts as the main character in the search for amrita. The relief narrates his physical and mental abilities to overcome challenges put to him by gods to prove his worthiness as a warrior hero. By the end of the story, Bhima manages to deliver amrita to his parents so that they can achieve final release from the world and ascend to heaven.

The existence of a giant Bhima statue found at the site (today kept at Dalem Hardjanegaran, a private royal house, in nearby Surakarta city) further confirms the importance of Bhima figural representations in the architecture of Sukuh. The statue stands almost two meters tall with his right hand holding a snake in front of his chest. One can clearly see long nails on both thumbs (locally known as pancanaka), which are recognized as one of Bhima’s weapons. The square pattern on the cloth covering his legs is interpreted as a checkered motif, a signifier identifying Bhima in wayang-play.

We do not know exactly when the temple of Sukuh ceased to be a ritual space, but we do know that the Javanese population had devoted their efforts towards building Islamic monuments since the early 16th century. However, the relationship between Sukuh and Bhima seems to have continued even after the temple’s original life had ceased. This continued significance can be found in the early modern Javanaese royal manuscript, Serat Centhini, produced in 1814 by the Surakarta court, which describes the already ruinous Sukuh as the former palace of the brother-in-law of Bhima, Brajadenta.

Visitors to the temple, both in the past and today, may be jolted by its sudden visual directness, boldly encouraging us to have an honest conversation with ourselves. The references to Bhima stories sculpted at Sukuh directs us to contemplate life/death and the soul’s release in solitude. For scholars of art and history, Sukuh offers an interesting case study on how past Javanese society commemorated seminal events using the innovative creations of chronograms.