An overwhelming dream

A woman sleeps in an elaborately decorated bed hung with fringed and tasseled curtains. A bearded man dressed in a frock coat stands in the bedroom and contemplates her, his chin in his hand. Behind him loom a disproportionately large table and chair, and under his feet the floor is flooded. He ignores both the surging waters and the two nude men at his feet clutching spars, apparent victims of a shipwreck.

We are looking at one of the many wildly incongruous scenes that make up Max Ernst’s Surrealist collage novel Une Semaine de Bonté (A Week of Kindness) This image of a man studying a sleeping woman directly suggests a key influence on Ernst and the Surrealists in general, the psychoanalytic theories of Sigmund Freud, particularly his study of dreams.

Following Freud, the Surrealists considered dreams a principal means to gain access to the unconscious, and they published many accounts of their own dreams in the journal La Révolution Surréaliste. Here, Ernst collaged together images cut from old book illustrations to depict a dream-like scene that has materialized in a woman’s bedroom and threatens to completely overwhelm the presumed dreamer and her observer.

Irrational juxtaposition

The Surrealists saw collage as a means to enact what they considered to be the fundamental poetic activity of the unconscious mind, the combination of disparate entities to create a new thing. Both Surrealist poets and artists used collage techniques. Like automatic writing, collage allows writers and artists to rapidly combine and juxtapose pre-existing elements, whether words or images, and transform them into new creations. This irrational juxtaposition of pre-existing elements mirrors the construction of dreams, which also bring together seemingly unrelated things to create strange narratives and scenes.

Max Ernst, Here Everything is Still Floating, 1920, printed paper collage with pencil on cardstock, 6 ½ x 8 ¼ inches (MoMA)

In Here Everything is Still Floating Max Ernst collaged images of a fish skeleton and a beetle onto a military photograph of an aerial bomb attack, thereby creating a seascape in which a steamboat encounters an enormous ghostly fish. We can identify the individual source images if we look closely, but they have been transformed by their new context, and their original significance is no longer relevant. They have become part of a new world.

Manifestations of the unconscious

Ernst was the first visual artist to join the Surrealist movement, and his early Dada collages such as Here Everything is Still Floating were an important catalyst for the development of Surrealism. As a Dadaist Ernst initially used collage techniques of juxtaposition to violate established expectations and rationality. For the Surrealists, however, the disruptions and dislocations of collage were not just arbitrary iconoclasm; they were direct manifestations of unconscious thinking.

The phrase

as beautiful as the chance encounter of an umbrella and a sewing machine on a dissecting table

from Les Chants de Maldoror by the nineteenth century writer known as the Comte de Lautréamont was a touchstone for the Surrealists. It embodied their notion that the union of disparate objects or words can result in new and marvelous creations. Ernst described the mechanism of collage in a more general way as “the coupling of two realities, irreconcilable in appearance, upon a plane that apparently does not suit them.” [1] What arises from that coupling is something previously unknown, a new reality.

Transforming ordinary things

Collage techniques were widely used in the 19th century by women making albums and decorative objects. In the 20th century they were adopted by the Cubist painters Picasso and Braque, who used them to expand their exploration of representational strategies and pictorial form.

Pablo Picasso, Guitar, Sheet Music, and Glass, 1912, collage and charcoal on board, 18 7/8 x 14 ¾ inches (McNay Museum, San Antonio)

Unlike the Cubists, the Surrealists were not interested in formal issues or in what they saw as narrowly aesthetic concerns. They viewed collage as a means to transform ordinary things, such as wallpaper, and turn them into points of entry to another world.

In his collage novels such as Une Semaine de Bonté, Ernst exploited the potential of collage to scramble the order of so-called reality to an extreme degree. He placed individual collage images of an imaginatively reordered universe into an extended visual narrative based on an illogical series of displacements and irrational re-integrations. To stress the independent existence of the imaginatively created world, these collages are seamless. Unlike Cubist collages, where the disparate parts remain clearly visible, Surrealist collages conceal the sutures between the constituent units, thereby emphasizing the final image’s “reality” rather than the procedures and materials of its creation.

A foundational technique

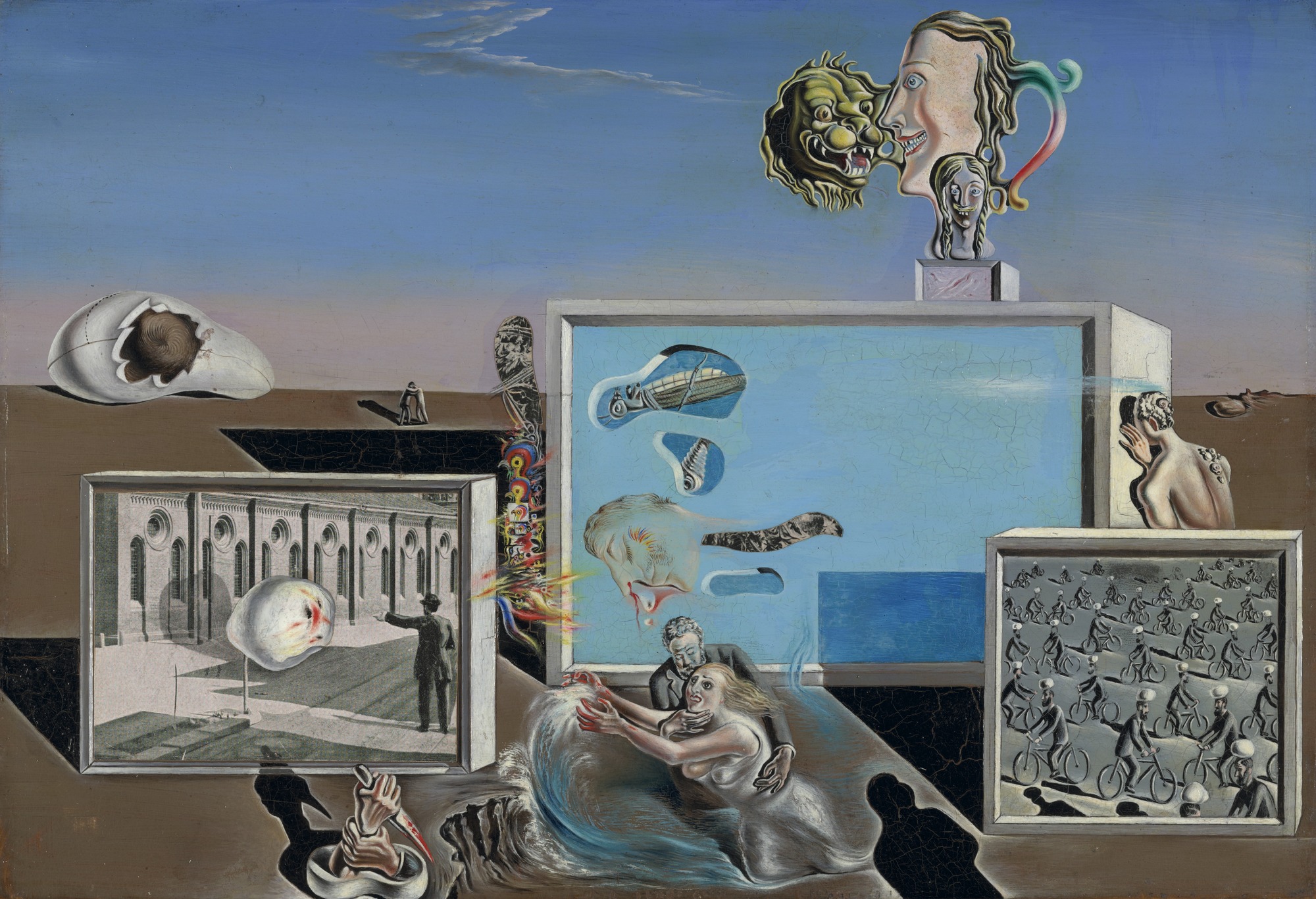

The basic mechanism of collage, irrational juxtaposition or the bringing together of radically incompatible things, was foundational for Surrealism, just as it is fundamental to the way dreams work according to Freud. Salvador Dalí combined collage and oil paint in some of his early Surrealist works, but even when he did not incorporate literal collage elements, the conceptual mechanism of the technique remains at the heart of his work. In Illumined Pleasures we see Dalí’s sleeping profile in the center surrounded by the incongruous objects of his unconscious thoughts.

In the foreground, directly below Dalí’s profile, a bearded man in a suit grabs a woman in a nightgown while both stand in water. Note the similarity to the Ernst scene we first looked at above; both works illustrate imagery Freud described as frequently appearing in dreams. Surrounding Dalí’s profile are what he called his “obsessions,” and these are grouped together in a collage-like presentation. Some of the figures are themselves conjoined images, such as the smiling woman’s head, which is also a foaming beer stein, and her neck, which is also a girl’s face in the shape of a mug.

René Magritte, Time Transfixed, 1938, oil on canvas, 57 7/8 x 38 7/8 inches (Art Institute of Chicago)

The conceptual mechanism of collage is also central to many of the paintings of René Magritte, which depict the irrational juxtaposition of disparate objects in a realistic style. In Time Transfixed a steam-train engine enters a room through the fireplace. The scale is impossible, but the details of the representation are so meticulous, including the cast shadow of the train and the steam going up the chimney, that we are led to consider this an accurate depiction of the world of dreams where such incredible combinations are commonplace.

The Surrealist juxtaposition of disparate entities, be it literal or conceptual, requires recognizable elements to achieve its surprising and innovative effects. This reliance on realistic representation differentiated Surrealism from most modern art movements, which rejected realism as an outdated concern with subject matter rather than artistic form. For the Surrealists, however, dedication to narrowly artistic concerns such as form, style and technique was an abdication of artists’ potential to change the world. Collage, with its ability to reshape reality in challenging, but still recognizable ways, was a central technique in the Surrealists’ revolutionary endeavors. It showed precisely how the mind could re-make the world in a concrete way, by using new and unexpected combinations of existing things to create a new reality.