The Great Pyramids at Giza, Egypt (photo: KennyOMG, CC BY-SA 4.0)

One of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world

The last remaining of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world, the great pyramids of Giza, are perhaps the most famous and discussed structures in history. These massive monuments were unsurpassed in height for thousands of years after their construction and continue to amaze and enthrall us with their overwhelming mass and seemingly impossible perfection. Their exacting orientation and mind-boggling construction has elicited many theories about their origins, including unsupported suggestions that they had extra-terrestrial impetus. However, by examining the several hundred years prior to their emergence on the Giza plateau, it becomes clear that these incredible structures were the result of many experiments, some more successful than others, and represent an apogee in line with the development of the royal mortuary complex.

Pyramid of Khafre (photo: MusikAnimal, CC BY-SA 3.0)

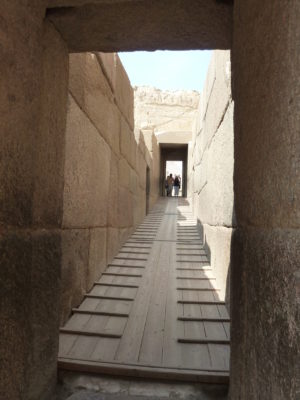

The causeway of the Khafre (Chephren) pyramid complex, taken from the entrance of the Khafre Valley Temple (photo: Hannah Pethen, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Three pyramids, three rulers

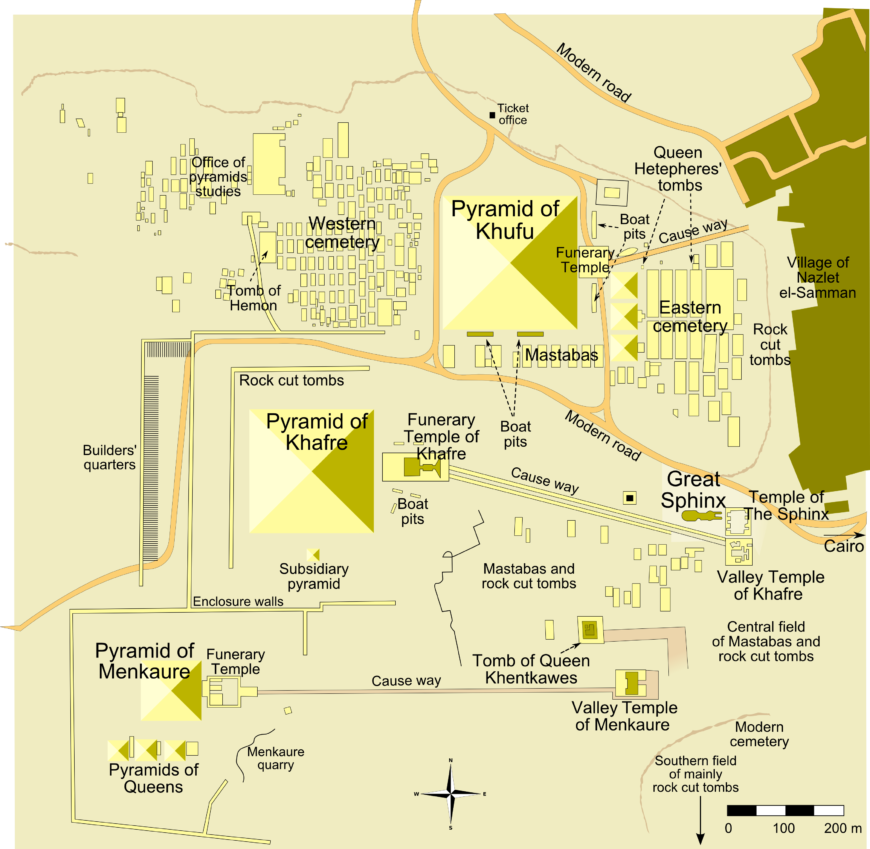

The three primary pyramids on the Giza plateau were built over the span of three generations by the rulers Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure. Each pyramid was part of a royal mortuary complex that also included a temple at its base and a long stone causeway (some nearly 1 kilometer in length) leading east from the plateau to a valley temple on the edge of the floodplain.

Other (smaller) pyramids, and small tombs

In addition to these major structures, several smaller pyramids belonging to queens are arranged as satellites. A large cemetery of smaller tombs, known as mastabas (Arabic for ‘bench’ in reference to their shape—flat-roofed, rectangular, with sloping sides), fills the area to the east and west of the pyramid of Khufu. These were arranged in a grid-like pattern and constructed for prominent members of the court. Being buried near the pharaoh was a great honor and helped ensure a prized place in the Afterlife.

Map of Giza pyramid complex (map by: MesserWoland, CC BY-SA 3.0)

A reference to the sun

The shape of the pyramid was a solar reference, perhaps intended as a solidified version of the rays of the sun. Texts talk about the sun’s rays as a ramp the pharaoh mounts to climb to the sky—the earliest pyramids, such as the Step Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara—were actually designed as a staircase. The pyramid was also clearly connected to the sacred ben-ben stone, an icon of the primeval mound that was considered the place of initial creation. The pyramid was viewed as a place of regeneration for the deceased ruler.

Construction

Many questions remain about the construction of these massive monuments, and theories abound as to the actual methods used. The workforce needed to build these structures is also still much discussed. Discovery of a town for workers to the south of the plateau has offered some answers. It is likely that there was a permanent group of skilled craftsmen and builders who were supplemented by seasonal crews of approximately 2000 conscripted peasants. These crews were divided into gangs of 200 men, with each group further divided into teams of 20. Experiments indicate that these groups of 20 men could haul the 2.5 ton blocks from quarry to pyramid in about 20 minutes, their path eased by a lubricated surface of wet silt. An estimated 340 stones could be moved daily from quarry to construction site, particularly when one considers that many of the blocks (such as those in the upper courses) were considerably smaller.

Backstory

We are used to seeing the pyramids at Giza in alluring photographs, where they appear as massive and remote monuments rising up from an open, barren desert. Visitors might be surprised to find, then, that there is a golf course and resort only a few hundred feet from the Great Pyramid, and that the burgeoning suburbs of Giza (part of the greater metropolitan area of Cairo) have expanded right up to the foot of the Sphinx. This urban encroachment and the problems that come with it—such as pollution, waste, illegal activities, and auto traffic—are now the biggest threats to these invaluable examples of global cultural heritage.

Aerial view of the Giza pyramid complex and development nearby (photo: © Raimond Spekking, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The pyramids were inscribed into the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1979, and since 1990, the organization has sponsored over a dozen missions to evaluate their status. It has supported the restoration of the Sphinx, as well as measures to curb the impact of tourism and manage the growth of the neighboring village. Still, threats to the site continue: air pollution from waste incineration contributes to the degradation of the stones, and the massive illegal quarrying of sand on the neighboring plateau has created holes large enough to be seen on Google Earth. Egypt’s 2011 uprisings and their chaotic political and economic aftermath also negatively impacted tourism, one of the country’s most important industries, and the number of visitors is only now beginning to rise once more.

UNESCO has continually monitored these issues, but its biggest task with regard to Giza has been to advocate for the rerouting of a highway that was originally slated to cut through the desert between the pyramids and the necropolis of Saqqara to the south. The government eventually agreed to build the highway north of the pyramids. However, as the Cairo metropolitan area (the largest in Africa, with a population of over 20 million) continues to expand, planners are now proposing a multilane tunnel to be constructed underneath the Giza Plateau. UNESCO and ICOMOS are calling for in-depth studies of the project’s potential impact, as well as an overall site management plan for the Giza pyramids that would include ways to halt the continued impact of illegal dumping and quarrying.

As massive as they are, the pyramids at Giza are not immutable. With the rapid growth of Cairo, they will need sufficient attention and protection if they are to remain intact as key touchstones of ancient history.

Backstory by Dr. Naraelle Hohensee