Torah crown (keter), Andrea Zambelli ‘L’Honnesta,’ c. 1740–50, silver, parcel gilt, Venice, 27.5 x 31.4 x 31.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

This remarkable silver crown, lavishly decorated with scrolling forms and an overabundance of flowers and vegetation, is surely fit for a king. However, this crown was not created to sit atop the head of a monarch, but to adorn a Torah—a scroll containing the first five books of the Hebrew Bible. The Torah’s luxurious adornments and its centrality in the synagogue (the place of Jewish worship) all indicate the Torah’s place as the holiest object in Judaism.

The Jewish people are known as the “people of the Book,” referring to the intimate connection between the Jews and the Torah. The Torah is the physical expression of the Jewish people’s connection with God and the centerpiece of the Jewish liturgy. On a typical day in a synagogue, you might see one or more Torah scrolls removed from the Torah ark, a central cabinet on the eastern wall of the synagogue, orienting prayer in the direction of Jerusalem. Typically, the scrolls are always dressed in ornate garments (a fabric or hard case) and decorated with ornamental finials and/or a crown surmounting their staves—all adornments intended to highlight the sanctity of the Torah.

Procession of Torahs in The Feast of the Rejoicing of the Law at the Synagogue in Leghorn, Solomon Alexander Hart, 1850, oil on canvas, Italy, 141.3 x 174.6 cm (Jewish Museum)

As the Torah is removed from the ark and processed throughout the synagogue on Shabbat, the congregation rises, honoring the Torah just as one might honor a king or queen. At this time, the adornments of the Torah are removed, so that portions can be read aloud each week (the entire Torah is read consecutively each year). Once the reading is complete, the Torah is redressed and once again paraded throughout the synagogue before being returned to the ark. This essay explores the vibrant artistic tradition that developed around the Torah and its decoration.

Hiddur Mitzvah: Beautifying the Torah

Torah ark with Torah ark curtain, tik, and dressed Torahs, Temple Beth Shalom, New Jersey (Ariel Fein, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The writing of the Torah scroll is subject to precise rules that allow little room for creativity. As a result of the clear stipulations of Jewish law (halakhah), the appearance and form of the Torah has remained consistent across time. The Torah is handwritten on parchment sheets sewn together to produce a long scroll. The ends of the scroll are affixed to and wound on staves (wooden rollers). Never decorated, the Torah scroll is above all a text, rather than a work of art. It is considered to be the word of God, and as such, the written word acquired unparalleled significance. Its unchanging appearance lends both authenticity and authority to the text.

However, because of its central place in Jewish liturgy, the Torah also inspired the creation of many types of Jewish ceremonial art intended to both protect the scroll against any damage as well as to enhance its appearance. These objects, through their proximity to the Torah, became sacred objects themselves.

The impetus for their creation and embellishment stemmed in large part from a custom that developed in the 3rd–6th centuries called hiddur mitzvah, literally meaning the beautification of a commandment. According to this principle, Jews should enhance a ritual—whether the reading of the Torah, or the observance of a holiday, among others—by moving beyond the basic demands of the law and using beautiful and precious materials. This interest in glorifying rituals gave rise to a rich visual tradition reflecting the varied experiences of Jewish communities across time and space. Let’s take a look at how Torah scrolls were embellished as part of this tradition of hiddur mitzvah.

Torah niche from the synagogue, 3rd century C.E., Dura Europos, Syria (Yale University Art Gallery)

Containing the Torah: The Torah Ark and its curtains

To protect and preserve the Torah scrolls, ornate stone and wooden cabinets, known as Torah arks, were built in synagogues. Described as a “holy ark” (aron hakodesh) or a “shrine of holiness” (heikhal hakodesh), they became the focal point of the synagogue’s furnishings. The design of the Torah arks often reflects local architectural forms. For example, the earliest Torah arks, known from the 2nd century C.E., imitated niches used by polytheistic communities in the ancient Roman Empire for the veneration of a statue (of the emperor or deity) or sacred object. An early 3rd-century painted niche in the synagogue of Dura Europos (in what is today Syria) followed this form. Just as the polytheistic niches were typically crowned by a conch shell (a symbol of sanctity), so too is the open niche for the Torah crowned by a conch. Four holes in the niche’s surface indicate that a curtain was used to cover the opening of the niche.

Open Torah niches in the background, Great Synagogue, Bukhara, 1896 (Elkan Nathan Adler)

In regions where the Torah ark was designed as an open niche, the Torah scroll itself was kept in a wooden or metal cylindrical case with a flat bottom called a tik (discussed more below). While most open niche Torah arks were eventually closed with doors, in some Sephardic and Mizrachi communities, the niche remained open into the 20th century, as in the Great Synagogue in Bukhara, where we see two open Torah niches housing tiks with textiles suspended from their finials, a custom practiced in many Mediterranean, and Central and West Asian communities.

Torah ark, Grande Scuola Tedesca, founded 1528, Venice (Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Closed Torah arks were often based on gate-shaped structures and placed on an elevated platform to suggest the ark as a gateway to heaven and add to its venerated character. In this Torah ark from the Grande Scuola Tedesca, one of the five extant synagogues in the Venetian Ghetto, the three-part Torah ark takes the form of an architectural style popularized in Italy by 16th-century Venetian Architect, Andrea Palladio. Palladio looked back to ancient Roman architecture and we see that reflected in the central section of the ark. Its two fluted Corinthian columns support, in the top center, a broken pediment (a pediment open or broken at the apex) decorated with urns and cornucopia. The doors of the ark are decorated on their exterior with the motif of the tree of life, while on their interior they feature the text of the Ten Commandments.

Torah ark curtain (parokhet), 1676, linen embroidered with silk and silver-gilt-thread and bordered with silver-gilt fringe, Venice, 190.5 x 165 cm (Victoria & Albert Museum)

A curtain called a parokhet hangs in front of the Torah scrolls within the Torah ark. Not only a decorative object, the curtain was meant to evoke the curtain that once hung in the ancient Tabernacle and the Temple in Jerusalem. Before the synagogue became the central space for Jewish spiritual, social, and communal life, the Tabernacle and later the Temple served as the focal point of the Jewish community. However, following the destruction of the ancient Temple in Jerusalem by the Roman army in 70 C.E., synagogues emerged as its substitute. In its liturgy and decoration, the synagogue adapted and evoked many of the rituals and symbols of the ancient Temple.

The Torah ark curtain is one example of this evocation of the ancient Temple—just as a curtain once hung before the holiest space in the Temple (which housed the two Tablets of the Law), so too does the synagogue curtain hang before the holiest space of the synagogue, before the Torah scrolls. Moreover, just as the Temple parokhet was made from the most sumptuous materials of the time, so too is the Torah ark curtain made from luxurious fabrics, such as intricately woven carpets and precious silks.

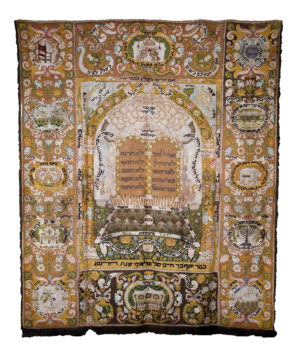

Torah Ark Curtain (parokhet), c. 1735, silk, embroidered with silk and metallic thread; metallic thread lace border, Istanbul, Turkey, 174 x 161.9 cm (Jewish Museum)

Torah ark curtains were also fashioned from repurposed or reused textiles. One example of reuse can be seen in an 18th-century silk and metallic thread Torah curtain from Turkey which features two large twisted columns flanking a central embroidered image of a mosque, (specifically the Blue Mosque, Sultan Ahmet Camii, in Istanbul with its six narrow minarets). Above is a small hamsa, a hand-shaped sign popular in both Muslim and Jewish contexts, as well as a Hebrew inscription dedicating the curtain to a local Istanbul synagogue. The hamsa and Hebrew inscription are visibly poorer in quality, suggesting that the textile was originally made for use in Istanbul by a Muslim and later acquired by the synagogue, when the inscription was added. For a Jewish resident of Istanbul, the Blue Mosque was a prominent part of the skyline, so the Torah curtain celebrated their city, while also providing the synagogue with an exceptionally precious embroidered textile to adorn its Torah ark.

Left: Bridal dress (bindalli), early 20th century, velvet, gilt metal threads, Edirne, Turkey (Israel Museum); center: A bride wearing the bindal dress after the wedding, early 20th century, Ruschuk (?), Turkey (Israel Museum); right: Torah ark curtain made from a woman’s dress, inscribed in Hebrew with dedication in memory of Jacob Him son of Mazal Tov, dedicated in 1929, velvet silk in a satin cotton frame, Izmir, Turkey, 185 x 156 cm (Israel Museum)

In the late 19th century, it was a common practice for Sephardic Jews in the Ottoman Empire to donate fabrics, such as bed coverings, pillowcases, or wedding dresses, to be reused as textiles within the synagogue. By donating such personal fabrics, donors ensured the preservation of their memory or their loved ones in the most sacred space of the synagogue. For example, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Jewish women adopted a new style of wedding dress then popular among the Turkish elite—the bindalli dress which was embroidered with flowers spreading from vases and other vegetal motifs on a dark velvet garment. Here, it was refashioned as a synagogue Torah ark curtain. As a result, the item of dress became a part of the community, permanently perpetuating the bride’s memory within the synagogue.

Tik, 1898 (date of inscription), silver, Baghdad (?) (Ariel Fein, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Wrapping the Torah: tik and mantle

As mentioned above, elaborate wooden containers (called tiks) and textile covers were developed to protect the Torah scrolls. Their design was informed both by the approach to the storage and use of the Torah in the liturgy. In some Sephardic and Mizrachi communities (Jews who trace their ancestry from the Iberian Peninsula and North Africa and West Asia, respectively), that used closed Torah arks, the form of the tik is suited to their specific reading style. During the public reading of the Torah in these communities, the hinged wooden case is stood upright on a table and opened to reveal the scroll wound on two rollers inside.

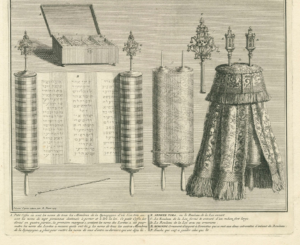

From left: Open Torah scroll with finials, Torah scroll wrapped with binder, Torah finial, Torah scroll dressed with mantle, Bernard Picart, 1725, Cérémonies et coutumes religieuses de tous les peuples du monde, engraving (College of Charleston Libraries)

In contrast, Ashkenazi communities (Jews who trace their ancestry to medieval France and Germany) drape the Torah scroll with a mantle, or a textile covering. During their worship services, the Torah scroll is laid flat on a reader’s table (tevah) with the staves of the Torah extending both above and below the scroll. As a result, the Torah mantle offered a fitting decorative cover that was easily removable prior to reading the text. As a removable object, many communities replace the Torah mantle used throughout the year (as well as the Torah ark curtain) with a white textile during the High Holidays. White is a symbol of purity and atonement, and is therefore appropriate to the penitential tenor of the holidays.

Embellishing the Torah: Finials and crowns

Torah finials (rimonim), c. 1863, silver, Iraqi Kurdistan, 25.5 cm (Israel Museum)

In addition to the Torah case, other objects were created to adorn and beautify the Torah, such as finials (rimonim), made from wood and silver, which are placed on top of the staves upon which the scroll is bound. While many rimonim are topped with round forms (likely due to the meaning of the Hebrew word rimon, or pomegranate), others, often North African and Sephardic or Sephardic-inspired finials, take the form of a tower, a motif often used to represent the Heavenly City of Jerusalem by Jews and Christians since the 4th century C.E. Bells often adorn rimonim, and may refer to the description in the Torah of the bells worn by Aaron, the High Priest in the Temple of Jerusalem.

A set of rimonim from Kurdistan feature spherical forms atop elongated staves. The two halves of the spheres can be separated, and the bottom filled with water. By virtue of the water’s proximity to the Torah, it was believed to become holy and could be used to help a mother during childbirth.

Left: Torah finials, (rimonim) and crown, Andrea Zambelli ‘L’Honnesta,’ c. 1740–50, silver, parcel gilt, Venice, 67.8 × 15.2 × 15.2 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art); right: Torah Crown, Moshe Zabari, 1969, silver, pearls on strings, New York, 40.6 x 26.8 x 22.5 cm (Jewish Museum)

The Torah crown (keter) is another important embellishment for the Torah typically modeled on the regalia of kings and queens to visually proclaim the significance of the Torah, often described as a “princess” or “bride.” Crowns can be used either in addition to or in place of rimonim, encircling the staves of the Torah. On the left, a set of Venetian silverwork rimonim and a paired Torah crown were commissioned together to be donated to an Italian synagogue and bear similar ornamentation. In contrast, the Moshe Zabari’s modern take on a Torah crown fuses the form of the Torah crown with rimonim, by reducing the rimonim and Torah crown to their most essential forms—the tubes fitted over the staves and the exuberant curves with suspended pearls that twist around them.

Left: Torah shield, 1867–72, silver, Vienna, Austria, 36.9 x 32.1 cm (Jewish Museum); right: Torah pointer (yad), 1872–1922, silver, coral, and semi-precious stones, Vienna, 4.4 x 22.9 x 4.4 cm (Jewish Museum)

Using the Torah: Shields and pointers

Torah dressed with pointer (yad), crown, rimonim, and mantle, Simeon Solomon, Carrying the scrolls of the Law, 1871, oil on canvas, 77 x 61 cm (private collection)

Other ceremonial objects related to the Torah addressed practical needs. The yad, or pointer, allows readers to follow the text without damaging the scroll with their hands. Often, the yad terminates in the figure of a hand pointing at the text.

Many synagogues own several Torah scrolls, both as a sign of the congregation’s prestige as well as for ease of use during the annual liturgy. As holidays require readings from different portions of the Torah (unrelated to the sequential weekly reading), it can become cumbersome to have to roll the Torah scroll to the appropriate place. The Torah shield developed in the 16th century as a decorative plaque hung around the Torah that could help readers identify the section to which a scroll was turned. Interchangeable silver plates with the names of holiday readings could be affixed to the shield. In an example from 19th-century Vienna the plate indicates the reading for the holiday of Sukkot. Although the Torah shield originated as a functional object, by the early 19th century, it had become purely ornamental, often decorated with motifs referring to the Torah ark and the holy scrolls contained within—a crown, the Tablets of the Law engraved with the Ten Commandments, and framed by lions, griffins and other creatures, meant to represent God’s entourage, among others.

Whether according to Jewish law or popular Jewish belief, the Torah emerged as the most sacred tangible Jewish object, and by extension, the ceremonial objects that developed alongside it became implements of holiness. [1]