Théodore Géricault, Raft of the Medusa, 1818–19, oil on canvas, 4.91 x 7.16m (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:05] We’re in the Louvre, looking at Géricault’s “Raft of the Medusa.” This is a massive painting.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:12] It’s 16 by 23 feet, and it’s important to remember that large paintings were reserved for important subjects. Subjects that were generally ennobling or that showed a heroic deed of some sort, and this painting could not be further from that. It’s not drawn from ancient Greek and Roman history. It’s not a biblical subject.

Dr. Zucker: [0:32] The story behind the subject is one of the most gruesome in the history of the sea, that had taken place just three years earlier.

Dr. Harris: [0:39] The title of the painting, “The Raft of the Medusa,” is referring to a ship called the Medusa.

Dr. Zucker: [0:45] It was part of a small fleet of ships that were trying to reclaim Senegal from the British as a French colony, and it had about 400 people on board. Many of them were settlers. There were about 150 soldiers.

Dr. Harris: [0:57] The man who was going to be the new governor of Senegal was also on board.

Dr. Zucker: [1:02] The problems began when the ship ran aground in the open ocean. There weren’t enough lifeboats. So, the captain ordered the ship’s carpenter to construct a raft from some of the lumber of the boat to hold everybody that couldn’t fit into the lifeboats.

Dr. Harris: [1:15] Well, naturally, those who went into the lifeboats were those of higher status — the captain, the officers, the politicians — and those that ended up on this makeshift raft were primarily the soldiers and the settlers. The idea was that the raft would be towed.

Dr. Zucker: [1:32] But within only a few minutes, when the captain realized that the lifeboat was being slowed by the raft, the line was severed and the raft was allowed to drift out to sea on its own.

Dr. Harris: [1:42] 150 people were abandoned at sea. What happened on the raft was horrific. There was starvation, murder, and of course, the worst thing imaginable that happened was cannibalism. There were even reports that some people were intentionally killed to provide food for the survivors.

Dr. Zucker: [2:04] And to preserve the small amounts of supplies that remained. All of this is depicted in wrenching detail. The artist interviewed survivors. He made a full-scale model in his studio. He created small stages with clay figures in order to organize the figures.

[2:18] He even retrieved body parts from the morgue, brought them back to his studio, in order to be able to accurately depict putrefying remains.

Dr. Harris: [2:26] You mentioned its naturalism, its realism, but in some ways, it’s not at all real. The bodies are clearly based on ancient Greek and Roman sculptures, on the studies of the nude figure that artists had to do at the Academy.

[2:41] This crescendo of this pyramid of figures; clearly, things were not organized in this way on the raft. This is a composition by an artist making a statement, saying something.

Dr. Zucker: [2:53] Creating a kind of anti-heroic painting that is still in the visual language of the Academy.

Dr. Harris: [2:59] The captain had been appointed by the king. The monarchy had been recently restored. You had this revolution that began in 1789 that established a republic in France that ended with the Napoleonic Empire and the restoration of a monarchy.

Dr. Zucker: [3:17] The king’s representative, the captain of the ship, failed. When Géricault is painting this canvas, he’s making a political statement that is anti-monarchic, anti-king.

Dr. Harris: [3:26] This was an incompetent captain who was appointed by the king and completely failed those he was entrusted to protect.

Dr. Zucker: [3:33] One of the most powerful aspects of this canvas is the composition. The corner of the raft is at the lower center point of the canvas, and it feels as if we can step onto it.

Dr. Harris: [3:43] The raft is tipped into our space; that corner is foreshortened. This composition is designed to draw us in and up. The artist did many, many sketches. He did his research, but in the end, made this decision specifically to draw us in.

Dr. Zucker: [4:00] To make this spectrum of emotion, from madness to despair. At the bottom left we see a father mourning that beautiful body of his dead son; to the upper right we see an expression of hope.

Dr. Harris: [4:12] The figure on the right pushes off with his right hand and lifts his left hand up in a last effort to be saved. All of the figures at this moment, when they see the ship on the horizon, actually a moment that they will not be rescued.

[4:27] The rescue will take place a couple of hours later, so this is actually a moment of false hope. There’s a sense of rotting bodies, the stench of death is present here to me.

[4:37] If we think about Neoclassical paintings like David’s “Oath of the Horatii,” we have figures from classical antiquity sacrificing their lives for a purpose. They are heroes.

[4:50] Here, human life is taken for no reason at all. People are dying because of incompetence, because of abandonment.

Dr. Zucker: [4:58] This is not Neoclassicism. Géricault is hoping to establish a style that we call Romanticism. This is a style that is concerned with human emotion, that is characterized by fluid brushwork, energized composition, with an emphasis on diagonals, on movement.

Dr. Harris: [5:13] You can think back to artists like Rubens, the “Elevation of the Cross,” the way that the bodies are fused together in a single motion.

[5:22] Romantic artists are looking back to Rubens. They’re not looking back as much to ancient Greek and Roman art, the way that the Neoclassical artists had done.

Dr. Zucker: [5:30] They’re also concerned increasingly with human experience and with the power and majesty of nature, here expressed in the wave on the left that threatens to crash over the raft.

Dr. Harris: [5:40] The Enlightenment had given people a sense that they could control their environment, that they could craft a better future for human beings, create a republic of laws, get rid of the corruption of the monarchy. Yet here the corruption of a king has had terrifying ramifications.

[6:00] The revolution had undone, in many ways, the power of the church. There’s no monarchy we can have faith in anymore. Romanticism is very much a style associated with this period after the failure of the revolution and the failure of the ideals of the Enlightenment.

Dr. Zucker: [6:17] As if to underscore that idea, one contemporary critic, after seeing this painting, said, “We are all on the Raft of the Medusa.”

[6:25] [music]

Théodore Géricault, Raft of the Medusa, 1818–19, oil on canvas, 4.91 x 7.16 m (Musée du Louvre, Paris, photo: Steven Zucker CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

A radical work of art

In 1819, a young man bolted through the streets of Paris. Years later, he said he must have looked crazy as he ran all the way home. He was the painter, Eugène Delacroix, and he had just seen Théodore Géricault’s astonishing painting, Raft of the Medusa, in the painter’s studio. Today, visitors to the Louvre museum stop in front of the painting as they make their way through the galleries, but in 1819 it was a truly radical work of art that astonished everyone.

Théodore Géricault, Raft of the Medusa, 1818–19, oil on canvas, 4.91 x 7.16m (Musée du Louvre, Paris, photo: Steven Zucker CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

A scene of desperation

The canvas is massive, measuring just over sixteen by twenty-three feet, so large that Géricault had to rent a studio big enough to house it as he worked. Standing in front of the painting, we see a raft, built of scrap lumber, rocking on the ocean waves. The eye is first drawn to the intertwined figures moving up the canvas to the right, bodies extended together as their arms gesture upward in a strong diagonal. At the top of the group, a Black man waves a piece of red and white fabric, signaling to a tiny ship deep in the background, as does a lighter skinned figure below him. All of the living people depicted in this striking pyramidal composition eagerly seek rescue, but among them are the dead and dying.

Detail, Théodore Géricault, Raft of the Medusa, 1818–19, oil on canvas, 4.91 x 7.16m (Musée du Louvre, Paris, photo: Steven Zucker CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

At the bottom left are those who have lost hope and the already dead. A grey-haired, bearded man, clad in a red head-covering, sits on the raft with his head resting on his right hand. His left hand grasps the torso of a pale young man, presumably his dead son, whose limp, alabaster body remains precariously extended on the edge of the raft.

Bodies on the verge of slipping beneath the water populate the lower portion of the painting. To the left of the father-and-son pair, we see the top half of a man arching back while his lower body, presumably, floats below. To the right of the father and son, lies a dark-haired figure, modeled by the artist Delacroix, lying face-down with his lower arm extended over a piece of wood. Next to him a pale corpse garbed in a white, with his legs caught in the wood of the raft, lies on his back with his head lost in the water of the ocean. The murky amber and green tone of the painting with strong contrasts of light and dark remind us that this is ultimately a scene of death.

Detail, Théodore Géricault, Raft of the Medusa, 1818–19, oil on canvas, 4.91 x 7.16m (Musée du Louvre, Paris, photo: Steven Zucker CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The father and son are near the base of another, larger triangle, that reaches up to the top of the mast with its billowing sail and down the rope on the other side of the composition.

150 people set adrift

When the work was exhibited in the Paris Salon of 1819, the public would have recognized the subject. It had been in the news just a few years before and quickly grew into a political scandal. In July 1816, a French naval ship, Medusa, was its way to Senegal carrying the new governor of the colony, his family, and some other government officials and others. The government officials came to secure French possession of the colony and to assure the continuation of the covert slave trade, even though France had officially abolished the practice. Another group aboard the Medusa was composed of reformers and abolitionists who hoped to eliminate the practice of slavery in Senegal by engaging the local Senegalese and the French colonists in the development of an agricultural cooperative that would make the colony self-sustaining.

The captain of the Medusa, who had received command of the ship through royal patronage, accidentally ran the ship aground on a sandbar off the coast of West Africa. The ship’s carpenter could not repair the Medusa and the decision was made to put the governor, his family and other high-ranking passengers into the six lifeboats. The remaining 150 passengers found themselves packed onto a raft made by the carpenter from the masts of the Medusa.

The group on the raft included lower-ranking military men, colonists, and sailors of European and African descent. The overcrowded makeshift raft, just 65 x 23 feet, was lashed to the lifeboats, but it impeded their progress so the more elite passengers in the boats took axes and cut the lines to the raft, casting it adrift. Of the 150 people aboard the raft, 15 were rescued by the Argus—the ship that we can barely see at the back of the canvas—and only 10 ultimately survived to tell the tale of cannibalism, murder, and other horrors aboard the raft.

Ripped from the headlines

Géricault made this drawing around 1818, when he was working out the composition for The Raft of the Medusa, by carefully studying and sketching ships and water conditions.” Théodore Géricault, Sailboat on a Raging Sea, c. 1818–19, brush and brown wash, blue watercolor, opaque watercolor, over black chalk on brown laid paper, 15.2 × 24.7 cm (The J. Paul Getty Museum).

There had never been a painting like Raft of the Medusa. It was on the grand scale of French history painting (think, for example, of Jacques Louis David’s Oath of the Horatii) but instead of ideal forms and a moralizing story from history, Géricault offered the Salon audience a thoroughly modern, Romantic depiction of death and suffering based on a contemporary event that was in the news. To create his painting, Géricault investigated everything about the story of the raft and talked with many of the survivors. He then brought all of the research together to create a radical painting that responded to the conservative tradition of history paintings.

Gericault first learned about the disaster in the Paris newspapers. Then two of the survivors, the ship’s surgeon, Henri Savigny, and the engineer, Alexandre Corréard, published accounts of their experiences on the raft. Géricault interviewed them both and worked with other survivors as well. The painter went to the French coast to study the movement of ships on the water. He examined images of the raft’s design and the Medusa’s carpenter, who had built the raft, gave Géricault a miniature copy of it. Géricault began drawing the bodies of the living and the dead, then working out the scene in watercolor and oil sketches trying to figure out what the show the viewers and just how to do it. The process required over 100 studies that moved through each episode of the story.

Tradition and radicalism

Gericault settled on a moment of, seemingly, false hope when those on the raft saw a ship, the Argus, and frantically tried to signal for rescue. The Argus passed them by but returned two hours later to rescue those who remained on the raft. In many ways the painting conformed to the expectations of the Salon, whose audience was accustomed to traditional history paintings. The canvas’s size signaled that it was following that tradition as did the highly organized composition based on two intersecting pyramidal forms that emphasized the unity of action.

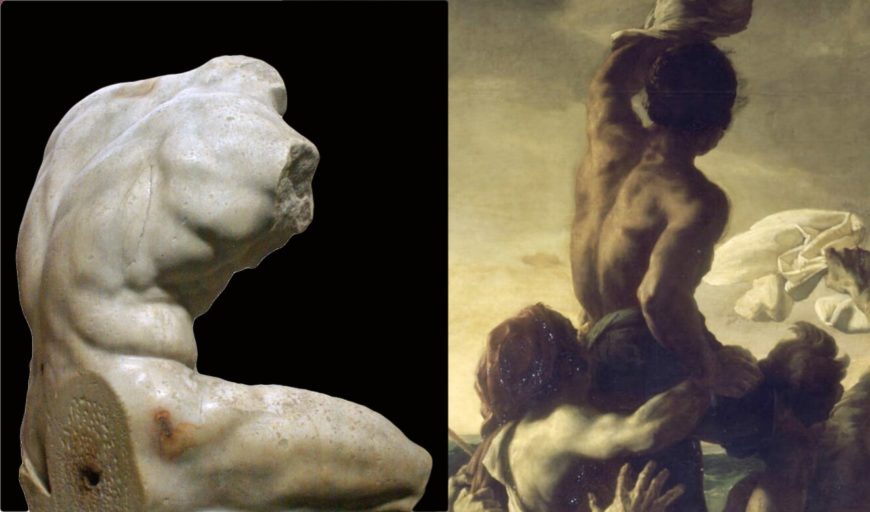

Left: Apollonios, Belvedere Torso, a copy from the 1st century B.C.E. or C.E. of an earlier sculpture from the first half of the 2nd century B.C., marble, 159 cm (Museo Pio-Clementino, Vatican Museums); right: detail, Théodore Géricault, Raft of the Medusa, 1818–19, oil on canvas, 4.91 x 7.16m (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

The viewers also recognized the poses of the figures. The view of the back of the man at the top of the triangle of figures signaling to the Argus, for example, was based on the famous Belvedere Torso, a fragment of a Classical sculpture depicting muscular nude male figure known by all artists in Europe. The older man grasping the body of his son recalled the Ugolino and his children, a story from the Renaissance writer Dante that inspired many artists. For many, the heightened emotion and tense figures called back to Michelangelo who inspired both academic and Romantic artists of the period.

Despite these more traditional elements, Géricault challenged everything about the conservative approach to art in Raft of the Medusa. The unified moment of a history painting, that should teach a lesson of moral virtue, is instead a scene of horror. The suffering figures then turn their backs on the viewer in a dark, dramatic light, reminiscent of Caravaggio. In a history painting like Jacques-Louis David’s Oath of the Horatii, for example, the painter presents the men and women directly to the viewer with a clear, even light, that makes it possible to see everything. In Raft of the Medusa, most of the living men depicted turn their backs on the viewer and the bodies that extend toward us are corpses. The carefully composed groups of figures and allusions to past art do not mitigate the impact of the dead bodies depicted on the raft and the futility of their loss.

Joseph

The figure based on the Belvedere Torso waving the red and white scarf challenged expectations as well. Instead of using a man whose light skin would mirror the white marble then associated with Classical sculpture, Géricault employed Joseph, a well-known model of Haitian descent (known to us only by his first name), whose dark skin challenged that expectation. The inclusion of a number of Black figures, modeled by Joseph, served to remind viewers that the voyage of the Medusa was embedded in colonization and the slave trade.

Shocking and new

No one who wrote about the painting in 1819 was unmoved. Conservative critics and writers were appalled and accused Géricault of creating a disgusting, repulsive mistake. More progressive writers who supported the modern, Romantic approach marveled at the artist’s shocking painting that caused them to tremble and admire the scene of the horrific events on the raft. When he ran through Paris after seeing Raft of the Medusa, completed in Géricault’s studio, young Delacroix experienced that same shock. He had seen something completely new that challenged every expectation for history painting and experienced an entirely kind of painting on a grand scale.