Left: Yaksha, c. 50 B.C.E., India, sandstone, 45.7 x 33 x 88.9 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art); right: Yakshi Holding a Crowned Child with a Visiting Parrot, c. 50 B.C.E., India, terracotta, 11.7 x 23.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Mythological figures often represented visually in a pair, the yaksha and yakshi are found across early Buddhist, Jain and Hindu art. Yakshas are male figures, and yakshis are their female counterparts. They were believed to be spirits that inhabited trees, mountains, rock mounds, rivers, and oceans. Their prevalence in sculpture, usually in association with natural elements, is considered a sign of widespread nature worship in the early historic period (6th–3rd century B.C.E.).

The earliest mentions of yakshas are found in the Jaiminiya Upanishad Brahmana, where the word is used only to describe a wondrous thing. By the time that epics such as the Ramayana were composed, yakshas were referred to as spirits or a group of figures similar to, but elevated and distinct from, ghosts and demons. In early Buddhist literature and sculpture, yakshas frequently appear in subordination to the Buddha; sources such as the Therigatha refer to them as guardian spirits who impart good morals. However, outside of the bounds of organized religions, many monumental yaksha figures were produced in the early historic period; these and some references in texts suggest that yakshas were worshipped as tutelary deities in some areas, as well as independent deities of trees or other natural entities.

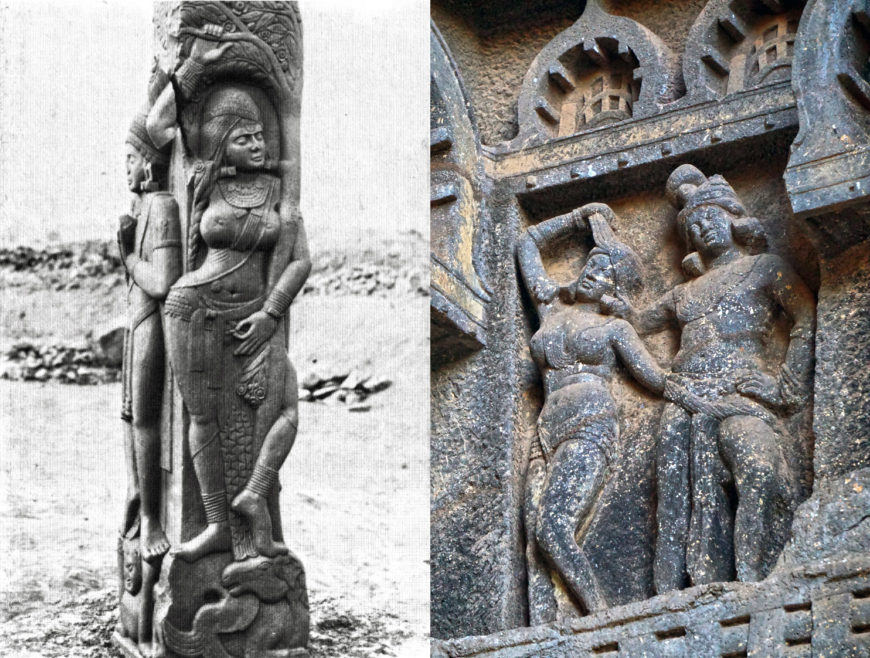

Left: Yakshi at Bharhut stupa, c. first century B.C.E., Madhya Pradesh; right: Mithuna, Karle Caves, Maharashtra, 2nd century C.E. (photo: Photo Dharma, CC BY-2.0)

In Tibetan Buddhist sources, yakshas and yakshis are claimed to be people who served an individual or a community during their lifetime, reborn as benevolent spirits. Jain texts similarly claim that these spirits are reborn as mortal human beings once their merit has been exhausted. These may indicate that growing Buddhist and Jain institutions attempted to appropriate hitherto independent nature deities and cults into their metaphysical systems.

Yaksha Manibhadra, from Parkham, Mathura, India, c. 150 B.C.E., 260 cm high (Mathura Museum; photo: Biswarup Ganguly, CC BY 3.0)

Among the earliest known images of yakshas and yakshis can be found in sculptural reliefs on the Bharhut and Sanchi stupas. They are generally depicted as attendant figures, sometimes to the aniconic Buddha. This may be seen in sculptures from the Mauryan and post-Mauryan period, such as the yakshas from Parkham and Vidisha and the yakshis of Besnagar and Didarganj. In the last centuries B.C.E. and early centuries C.E., the yaksha iconography adopted softer features such as a prominent belly.

This is especially prevalent in sculptures of Kubera, considered the king of yakshas in some traditions, but also the god of wealth in others. He is depicted with abundant jewelry and wears a dhoti tied underneath a protruding belly. The yaksha figure from Pitalkhora, Maharashtra, may be considered an example of Kubera iconography. Kubera’s mounts include a horse, elephant or a ram. He is also depicted holding a mace or a club.

The yaksha Manibhadra was also considered an important figure, with several Buddhist, Jain and Hindu literary references to his popularity and worship. The yaksha sculpture from Parkham is widely believed to be a representation of Manibhadra.

Didarganj Yakshi, 3rd century B.C.E., polished sandstone, Didarganj Kadam Basul, Eastern Patna, India, c. 162 cm high (Patna Museum, India)

Yakshis are generally depicted as voluptuous figures with nude upper bodies, wearing necklaces, bangles, and anklets. Their lower torsos and waists are decorated with clothing and more jewelry. Due to their associations with the natural world, they are often represented next to or holding onto trees—such yakshis are referred to as shalabhanjikas, which may reference the birth of the Buddha under the sala tree by his mother, Maya. They might also hold a pot with water or a lotus flower, both associated with fertility, or might be represented alongside a makara or naga.

Bhutesvara Yakshis, 2nd century C.E., red sandstone, 64 inches high (Mathura Museum, India; photos: Biswarup Ganguly, CC BY 3.0)

Yakshi figures are sometimes depicted standing on top of figures short in stature, that are depicted with unsmiling faces, and fearsome expressions, as seen in the Kushan period Bhuteshwar yakshi reliefs.

Enthroned Jina Attended by a Yaksha, a Yakshi, and Chauri-Bearers, 9th–10th century, copper alloy, India (Karnataka), 24.8 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Though yakshas and yakshis faded in popular Buddhism and Hinduism by the middle of the first thousand years C.E., they were adapted in some Tantric Buddhist rituals as the fulfillers of wishes. They continued to be depicted and sometimes worshipped in Jainism through the early and late medieval periods, starting in 500 C.E. and up until the 15th century, where they are portrayed as attendant figures to the twenty-four Tirthankaras, with the yaksha on the left and yakshini on the right side.

Drawing from articles on The MAP Academy