Zoroastrianism is one of the world’s oldest known living religions and has its origins in the distant past. It developed about three and a half thousand years ago from the ancient Indo-Iranian religion that was once shared by the ancestors of nomadic herding tribes that later settled in Iran and northern India. Zoroastrianism thus shares a common heritage with the Vedic religion of Ancient India and Hinduism. It is thought to have taken root in Central Asia during the second millennium B.C.E., and from there spread south to Iran. In particular, the regions of Sistan and the Helmand basin play an important part in Zoroastrian imagery, suggesting that this area was a center of Zoroastrianism from early on. Zoroastrianism became the foremost religion of the Achaemenid (550–330 B.C.E.), Parthian (247 B.C.E.–224 C.E.) and Sasanian (224–651 C.E.) empires, engaging with the religions of the Jews and with nascent Christianity and Islam.

Zoroastrianism lost its dominant position when the Arabs invaded and defeated the Sasanian Empire, although it lived on especially in rural areas of Iran until the Turkish and Mongol invasions in the 11th and 13th centuries. It was only then that Zoroastrians withdrew to the desert towns of Kerman and Yazd. Today they form a religious minority in Iran of 10–30,000 persons. Soon after the Arab conquest of Iran in 651 C.E., there was an exodus of Zoroastrians from Iran to the Indian subcontinent where they settled and became known as the Parsis, and became an influential minority under British Colonial rule. From there Zoroastrians migrated to other parts of the world especially Britain, America, and Australia, where they form diaspora communities today.

What do Zoroastrians believe?

Zoroastrians believe that their religion was revealed by their supreme God, called Ahura Mazda, or ‘Wise Lord’, to a priest called Zarathustra (or Zoroaster, as the Greeks called him). Zarathustra is held to be the founder of the religion, and his followers call themselves Zartoshtis or Zoroastrians. Central to Zoroastrianism is the profound dichotomy between good and evil, and the idea that the world was created by God, Ahura Mazda, in order that the two forces could engage with one another and the evil one will be incapacitated. With this is the belief in an afterlife that is determined by the choices people make while on earth, the final and definitive defeat of evil at the end of time and a restoration of the world to its once perfect state.

What are the key sacred texts of Zoroastrianism?

These religious ideas are encapsulated in the sacred texts of the Zoroastrians and assembled in a body of literature called the Avesta. Composed in an ancient Iranian language, Avestan, the Avesta is made up of different texts, most of which are recited in the Zoroastrian rituals, some of them by priests only, others by both priests and laypeople. These texts were composed orally at different times, and the oldest of them, the so-called Gathas, or ‘songs’ of Zarathustra, the Yasna Haptanghaiti and two prayers, probably date from some time in the mid- to late second millennium B.C.E. These texts are referred to as Older Avesta as their language is more archaic than that of the rest. The Younger Avesta is not only linguistically more recent, but also much greater in volume and shows a more advanced stage of the religion’s development. The Gathas are traditionally attributed to Zarathustra, the eponymous founder of the Zoroastrian tradition. All Avestan texts were composed and transmitted orally, although presumably from the late Sasanian period onwards there also existed a written tradition.

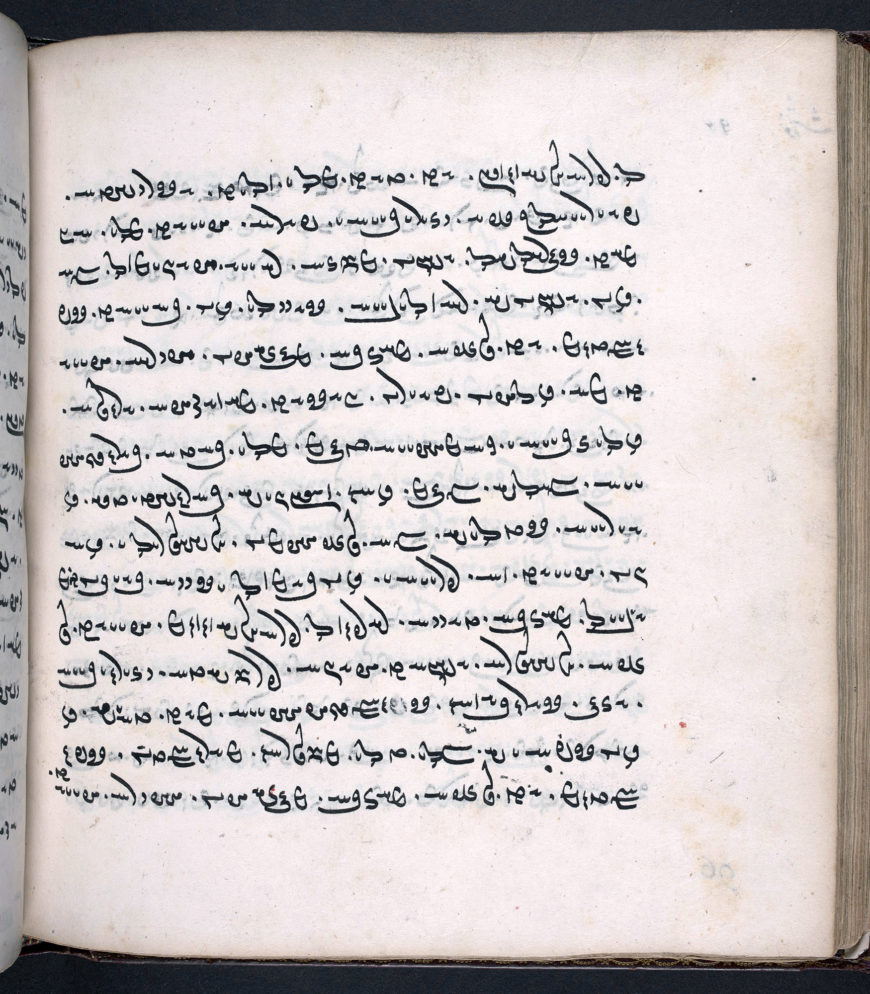

A 17th-century Iranian copy of the Zoroastrian manual for the Yasna ritual. The Avestan text of this manuscript includes ritual instructions in Pahlavi written in red ink. This 17th-century copy was written in Iran. It was probably the first Zoroastrian sacred text to be brought to England. The Avestan Yasna sādah, early 17th century, (Arundel Or 54, British Library)

The poetic power of these texts, which are at the heart of the Avesta or Zoroastrian sacred literature, can still be appreciated today. The five Gathas consist of seventeen hymns, which together with the Yasna Haptanghaiti form the central portion of the key ritual of the Zoroastrian tradition, the Yasna of seventy-two chapters. The daily Yasna ceremony, which priests are still required to learn and recite by heart, is the most important of all Zoroastrian rituals. Folios 96-97 of this copy of the Yasna sādah, or ‘pure’ Yasna (i.e. the Avestan text without any commentary), contain the end of Yasna 43 and the beginning of Yasna 44. Arguably one of the most poetic sections of the whole Avesta, Yasna 44, consists of rhetorical questions posed to Ahura Mazda about the creation of the universe, such as who established the path of the sun and the stars, who made the moon wax and wane, and who holds the earth down below and prevents the clouds from falling down? The implied answer, of course, is that Ahura Mazda has arranged all of this.

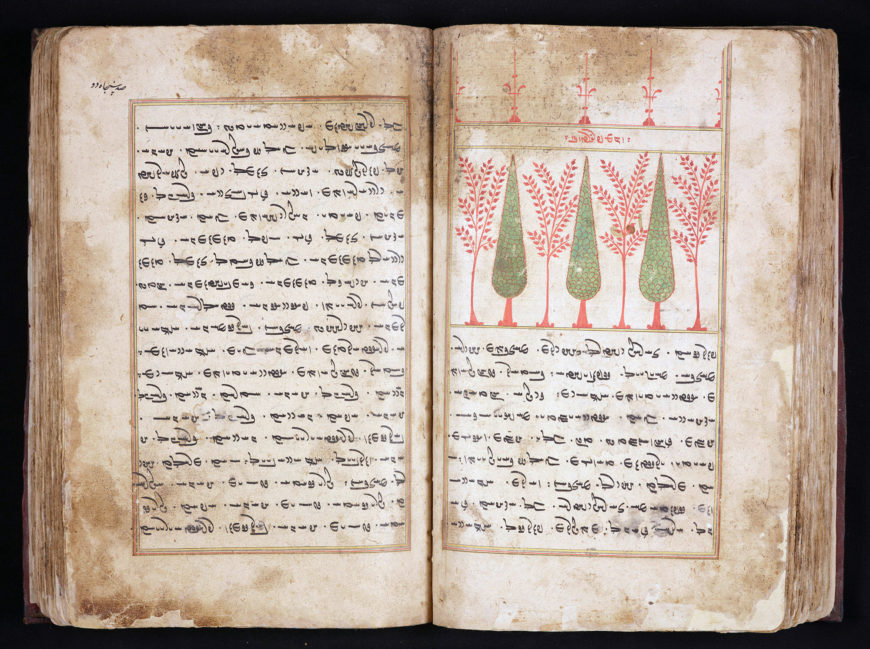

An illustrated copy of the Avestan Vīdēvdād Sādah, the longest of all the Zoroastrian liturgies. Copied in Yazd, Iran, in 1647 (RSPA 230, British Library)

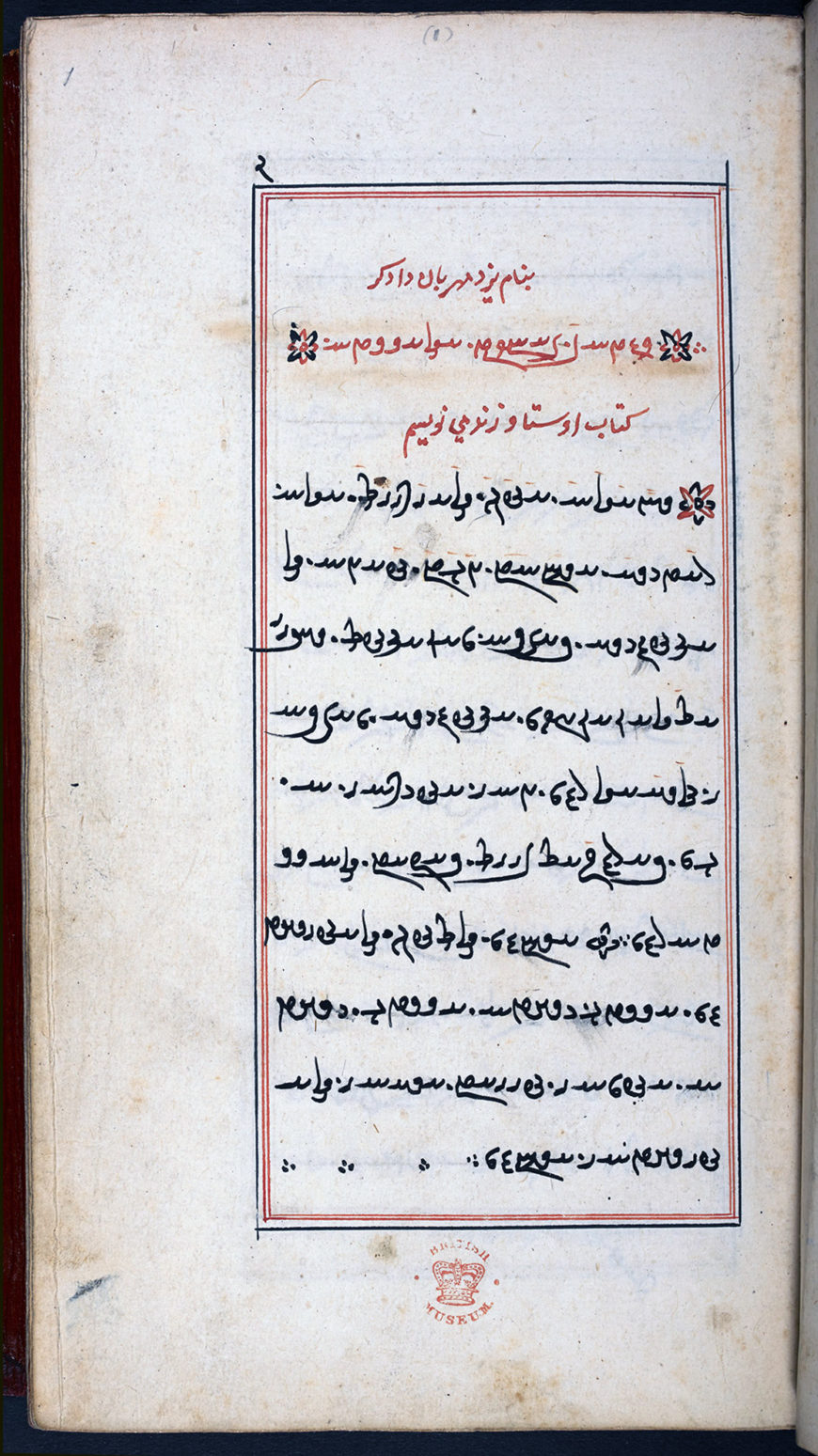

The Khordah Avesta (‘small Avesta’) contains prayers, hymns and invocations recited by priests and lay people in daily worship. This image shows the first page of a manuscript which begins with the Yatha ahu vairyo (‘Just as he is to be chosen by life’) and the Ashem vohū (‘Good order’), two of the holiest Zoroastrian prayers. 1673 (Royal MS 16 B VI, British Library)

Writing the ritual instructions in red ink helped the priests to navigate through the manuscript. Very few existing manuscripts also show illustrations. The British Library is home to one of them. It is a beautifully written and decorated copy of a ceremony called the Vīdēvdād, and shows seven coloured illuminations, all of trees. The manuscript was copied in Yazd, Iran, for a Zoroastrian of Kirman in 1647. The heading here has been decorated very much in the style of an illuminated Islamic manuscript.

The Vīdēvdād, or Vendidād as it is also known, is chiefly concerned with reducing pollution in the material world and represents a vital source for our knowledge and understanding of Zoroastrian purity laws. Folio 151 verso shows the beginning of chapter nine of the Zoroastrian law-book, which concerns the nine-night purification ritual (barashnum nuh shab) for someone who has been defiled by contact with a dead body.

The Yasna, Vīdēvdād and other rituals are recited and performed by priests inside the fire-temple. In addition, the Younger Avesta comprises devotional texts recited by both priest and lay members of the community, male and female alike. There are twenty-one hymns, or Yashts (Yt), dedicated to a variety of divinities whose praise is not only legitimised, but demanded by Ahura Mazda, who presides over them all. In the Zoroastrian calendar, each of the thirty days of the month is dedicated to one particular deity whose name it bears and whose hymn, or Yasht, is recited on that day.

The individual deities are also invoked for particular tasks. Mithra, for instance, is the deity who watches over contracts, while Anahita is especially close to women and helps them conceive and give birth. In addition, there are short prayers, blessings and other texts collected in the Small, or Khordah, Avesta.

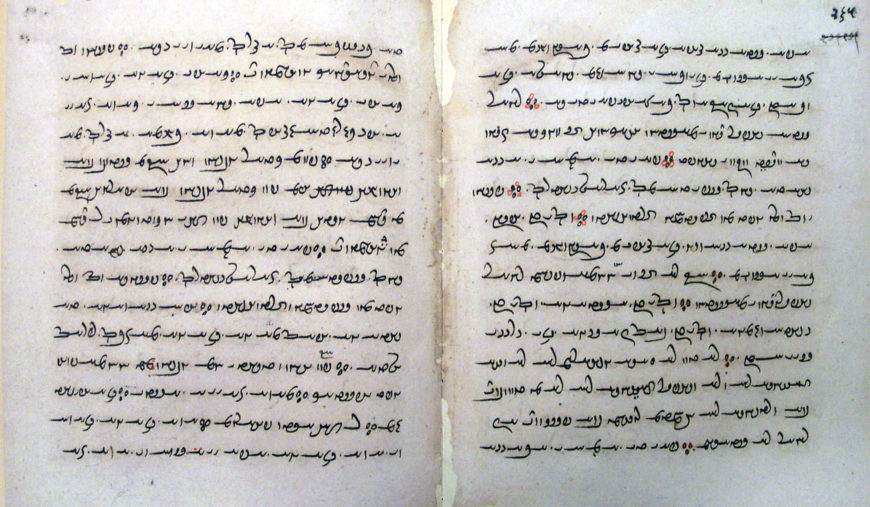

This is a copy of the Vīdēvdād accompanied by its Pahlavi translation and interpretation. It is one of the oldest existing Zoroastrian manuscripts, copied in 1323 in Nawsari, Gujarat. In this manuscript, each sentence is given first in the original Avestan (Old Iranian) language, and then in Pahlavi (Middle Persian), the language of Sasanian Iran (Avestan MS 4, British Library)

In addition to manuscripts providing the Avestan texts to be recited in the rituals, there is a second group of bilingual manuscripts, which give the Avestan text together with its translation into Pahlavi.

As the tradition of the Avesta was entirely oral, its translation and explanation would have been memorized together with the Avesta, although the exegesis, called Zand, was more flexible and open to being altered and expanded. The Avesta was eventually written down in an alphabet designed especially for this purpose and developed on the basis of a cursive form of the Pahlavi script. The tradition of the Avesta and its exegesis that has come down to the present day is that of the province of Pars, the centre of imperial and priestly power during the Sasanian era. The Avesta script was invented artificially, presumably around 600 C.E., in the province of Pars in order to write down the sound of the recitation at a time when the meaning of the texts had long been forgotten. The script is based on the Pahlavi script which had been in use for many centuries for writing Middle Persian texts. The Pahlavi script in turn is derived from Aramaic, the chief administrative language of the Achaemenid Empire. It contains only consonants and is read from right to left.

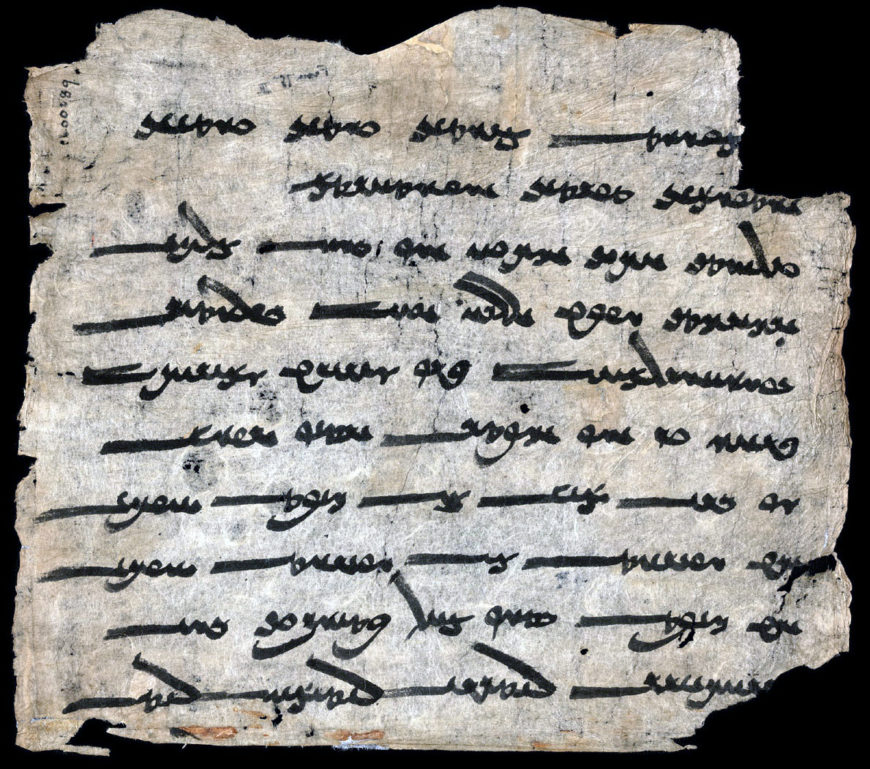

One of the holiest Zoroastrian prayers, the Ashem vohū, this manuscript discovered at Dunhuang by Aurel Stein in 1917. 9th century (Or 8212/84, British Library)

There is, however, a unique document from Central Asia, the so-called Sogdian Ashem vohū, which records the Avestan words of one of the Zoroastrian sacred prayers in Sogdian (a medieval Iranian language) script. Dating from the 9th century C.E., this document is the oldest extant Zoroastrian manuscript, predating the Avestan manuscripts by about 300 years. The Ashem vohū prayer occupies the first two lines of the text and shows features of the local pronunciation of Avestan in Sogdian, unaffected by the way Avestan was pronounced in the province of Pars. The rest of the text tells a story of Zarathushtra coming before and paying homage to a ‘supreme god’ (presumably Ahura Mazda) in Paradise.

Originally published by the British Library

Almut Hintze

Almut Hintze is Zartoshty Brothers Professor of Zoroastrianism at SOAS, University of London, and Fellow of the British Academy. She specialises in Zoroastrianism and the tradition of its sacred texts, of which she has published several editions. She currently directs a collaborative project on the Multimedia Yasna, funded by European Research Council (2016–2021), to produce an interactive film of a complete performance of the Yasna ritual, electronic tools for editing Avestan texts, and a text-critical edition, translation, commentary and dictionary of the Avestan Yasna.