In a rational world, cookbooks would be dead. Hard-bound, oversized, resource-heavy, time-intensive, stubbornly static, overpriced, and packaged without a semiconductor, they are artifacts of another era. Cookbooks make as much sense as a card catalog, and even a modest collection takes up almost as much room in your library.

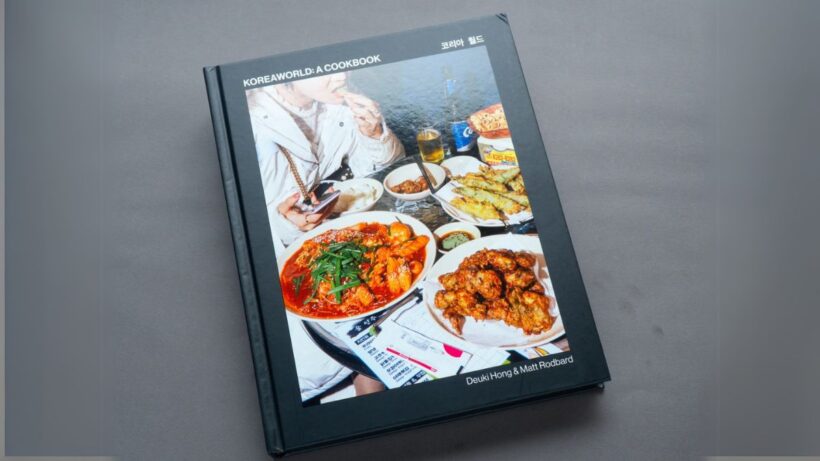

Thank heavens that, as the legendary magazine editor George Jean Nathan put it, “Great art is irrational, mad with its own loveliness.” Despite prevailing trends—toward the ephemeral, the endless scroll, the hosting of everything in the ever-present “cloud”—cookbooks are booming. One needn’t foolishly attempt a rational explanation for this. Simply purchase Koreaworld and go happily mad.

Matt Rodbard and Deuki Hong have practiced their lovely irrationality for over a decade. Their 2016 surprise Koreatown became one of the most celebrated cookbooks of the year, beloved by home cooks, lauded by haute chefs. Koreaworld isn’t merely a sequel; it’s an exercise in scaling up, a cookbook broadly scoped and rightly sized to accompany the extraordinary explosion in Korean culture worldwide. A cultural virality is due in part to the concept of Hallyu: the focused, coordinated investment on behalf of the South Korean government to export Korean dramas, gaming, music, and, of course, food. As any underpaid marketing manager in Tulsa might tell you, the best bureaucratic boosterism can’t sell a culture that lacks sex appeal. But when the bureaucrats get to sell bokkeumbap? Hallyu-yah. Whatever the opposite of a diaspora is, Rodbard and Hong show you what it looks like, collecting the recipes and narratives of communities around the world who have been drawn into the magnetic, proselytizing force of Korean food. We’re all citizens of Koreaworld now.

Despite such gargantuan context, Rodbard and Hong insist you should not mistake Koreaworld for an encyclopedia. They needn’t worry: If the promise of the web is everything-all-at-once, the particular thrill of a cookbook is a very particular point of view on…not-everything. Here are expert curators, picking over stories, ingredients, combinatory experiments, history, heritage, and innovation like a sous selecting the finest perilla leaves. The resulting amalgam is not unlike the Korean dinner tables the authors celebrate: surprising, diverse, euphoric, yet somehow still unified and grounding. Finished off–perhaps surprisingly–with extremely good coffee.

Rodbard and Hong are clever companions, voicey and opinionated, respectful and rebellious, curious and returning most frequently to states of pure pleasure and wonder. But blur the words and Koreaworld still wins. One might controversially claim that a cookbook is only as good as its images, and here the transportive, nearly mystical photography of Alex Lau is as close as a cookbook can get to smell-a-vision.

There’s a simple test for a great cookbook. Try it on the next one you’re thinking of buying. Does it make you want to cook? To launch yourself from the coffee table to the kitchen counter? There can certainly be a kind of voyeuristic pleasure in the fussy, precious, self-serious tomes of the Michelin breed. Still, the real secret behind the cookbook genre’s death-defiance is its ability to stir potential energy into kinetic.

Koreaworld passes the test. And in so doing, reminds us of the larger project great cookbooks are engaged in. Koreaworld isn’t only promotion; it’s preservation. In globalization is the preservation of taste; in innovation, the continuation of tradition; in exportation, the expansion of appreciation. It’s in the cookbook that constraints of an outmoded form factor are found in the depth required to perceive new dimensions of taste.