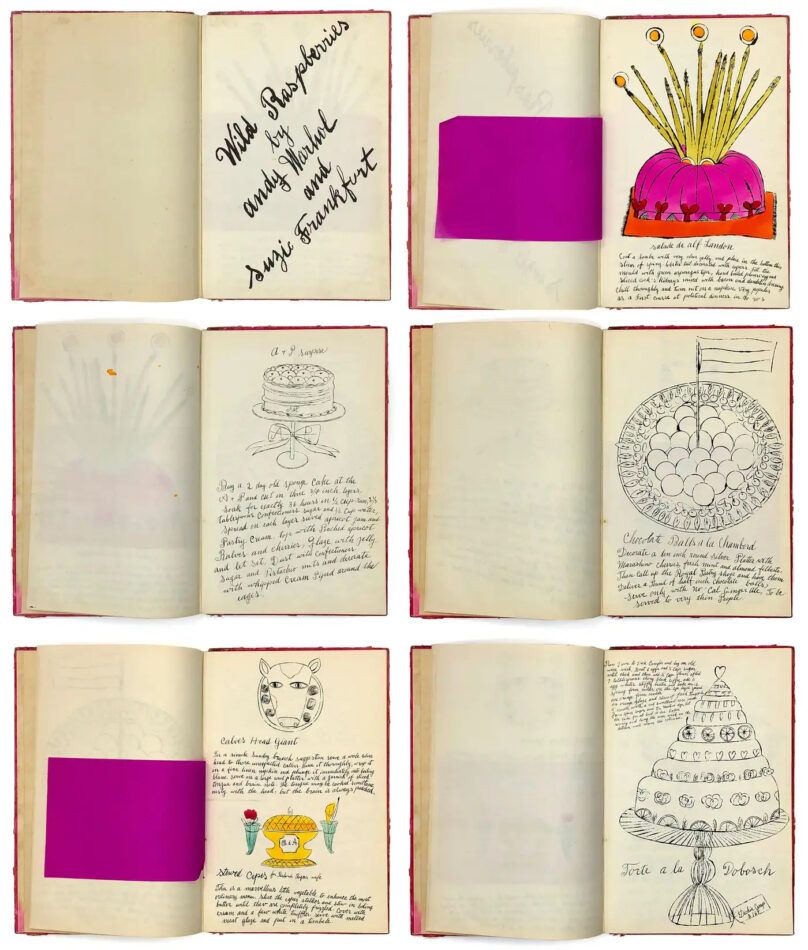

It’s a little-known fact that Andy Warhol cooked. And not just soup. But that was never the point of Wild Raspberries, the self-published illustrated cookbook he made in 1959 with a friend, the renowned interior decorator Suzie Frankfurt, before he catapulted to Pop art fame.

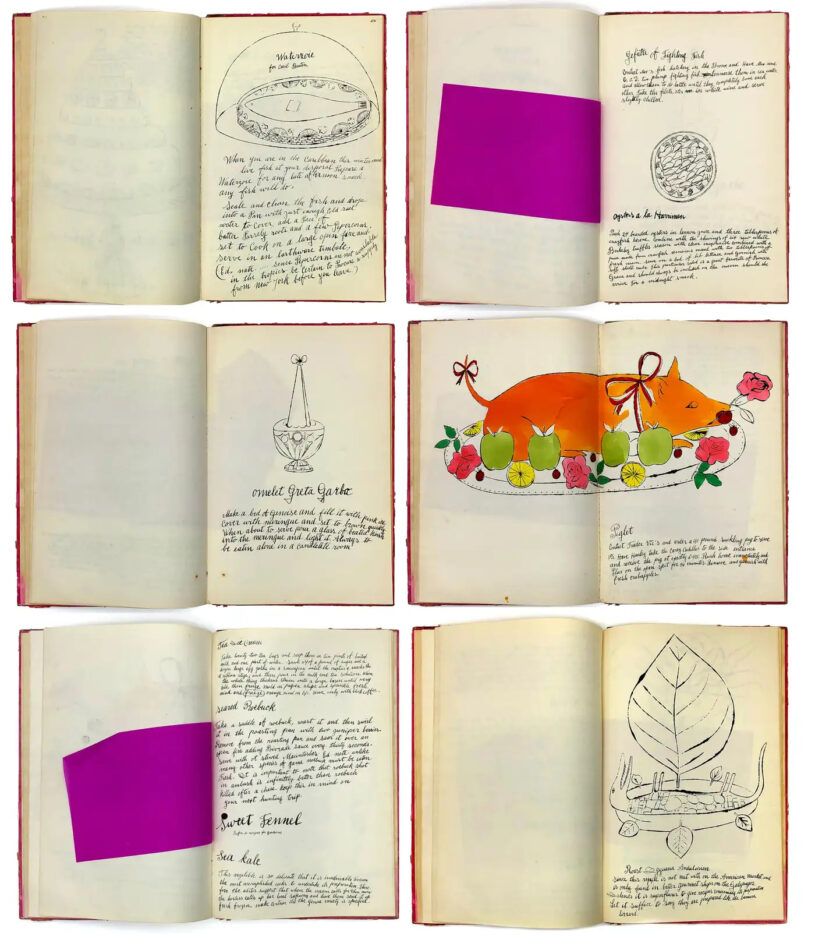

From the start, their culinary project was a spoof — a poetic parody of the elaborate French recipes popular with homemakers in 1950s America. Far from offering real instructions, the “recipes” are more like witty directives from one hostess to another, a wink and a nod to entertaining in busy Manhattan social circles and the actual lack of cooking. The one for Chocolate Balls à la Chambord, for instance, tells readers to “call up the Royal Pastry shop and have them deliver a pound of half inch chocolate balls, serve only with no-cal Ginger ale.”

Warhol and Frankfurt tried to sell Wild Raspberries at Bloomingdale’s department store and at bookshops, and some orders were taken. But as he did with his other early books, Warhol gifted many to friends and clients for Christmas. Around 34 copies were produced in 1959, and they’re not easy to find. Gallery Art, a print specialist in Aventura, Florida, is currently offering one of those originals on 1stDibs. “It’s an incredible look into the lightheartedness that follows Andy Warhol throughout his development as one of the most important American artists of the second half of the 20th century,” says Gallery Art’s Waseem Asrani.

Wild Raspberries is one of eight books that Warhol made on the side while working as a commercial artist in advertising and fashion in New York between 1952 and 1960. He drew the pictures of food while Frankfurt wrote the recipes, which were transcribed below the images by Julia Warhola, Warhol’s mother, in her distinctive curlicued calligraphy. Warhol reproduced the drawings via offset printing and then brought the pages to book-binding rabbis downtown. The authors jokingly named their book after Ingmar Bergman’s 1957 film Wild Strawberries.

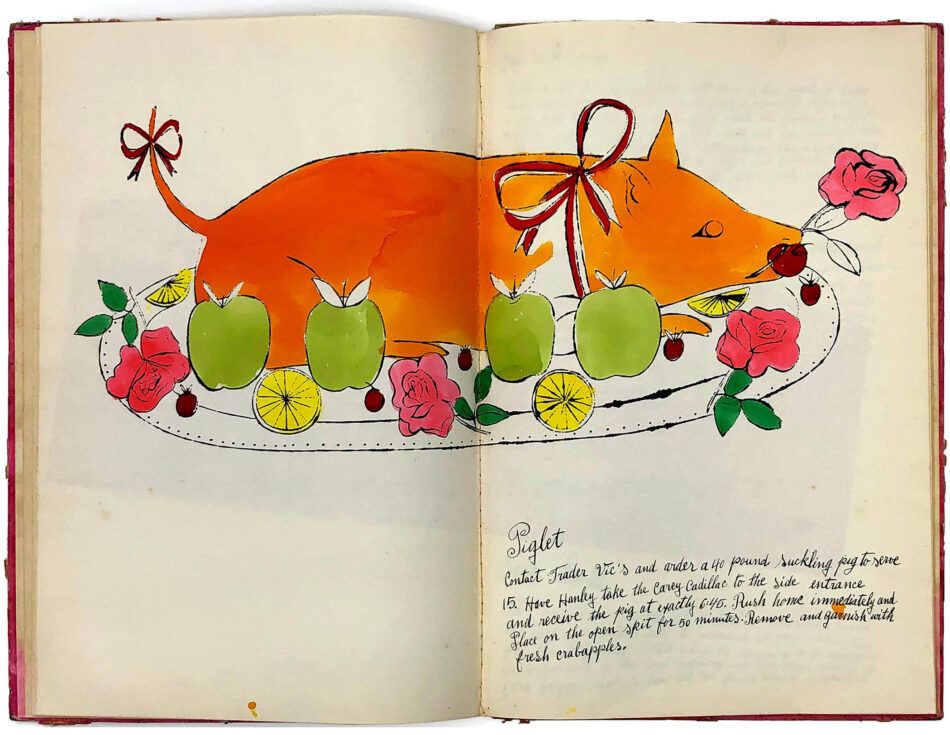

In this copy, 3 of the 19 offset lithograph images — a suckling pig surrounded by green apples, a pink gelatin mold with asparagus tips and cartoonish lobster tails, and a golden tureen — are hand colored with still-vibrant watercolor. As he often did with his early drawings, Warhol invited others (in this case, schoolchildren who lived upstairs from him) to do the coloring, providing them with explicit instructions. And he didn’t mind mistakes, as we can see throughout the book, particularly in his mother’s imperfect punctuation. That’s all part of the charm.

Although the project predates the Factory, Warhol’s legendary studio, his collaborative process foreshadows the assembly line approach he’d take when producing his iconic silkscreened paintings the following decade.

The cookbook drawings are classic early Warhol, delightfully whimsical, redolent of children’s book illustrations and festooned with flowers and other decorative flourishes. He made them using his trademark blotted-line technique, in which he drew the image in pencil and traced over it using a fountain pen before pressing a second piece of paper to the ink to make a monoprint. The process resulted in a broken line that looked as if it had, in fact, been printed. (Warhol liked the effect, he once said, because if something had been printed repeatedly, it meant it had a large audience.)

It’s an enchanting, idiosyncratic aesthetic, one that immediately struck Frankfurt when she first encountered his drawings, displayed at Serendipity, a popular ice-cream parlor and social hub on Manhattan’s East Side.

“I had never heard of him, but I was mesmerized by the work,” Frankfurt, who died in 2005, wrote in the preface for a mass printing of the book in 1997. She remarked on the “magical watercolors of flowers and butterflies” she first saw. “There was something about those illustrations that was so appealing that I made a determined effort to meet the artist.”

The two became fast friends, sharing a love of shopping and lunching, as well as a sharp wit and an appreciation for inside information. The recipe for Piglet begins: “Contact Trader Vic’s and order a 40 pound suckling pig to serve 15. Have Hanley take the Carey Cadillac to the side entrance and receive the pig at exactly 6:45.”

“We thought we’d sell thousands,” Frankfurt told writer William Norwich in the Observer in 1997. “We sold 20.”