In the 1990s, British artist Richard Caldicott began photographing an unlikely subject: Tupperware containers. But rather than communicate the symbolic banality of these domestic vessels, as some artists interested in found objects might have done, Caldicott transformed them into ethereal, glowing geometric abstractions.

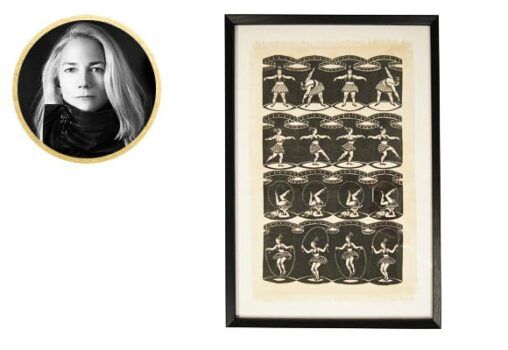

The large-scale limited edition photograph Untitled #168 (Abstract Photography), 2000, attests to Caldicott’s creative eye and technical mastery, with its vivid color, luminescence and elegant sense of proportion and volume.

It’s no wonder that his work is sought after by serious photography buffs. An edition of this photo is one of 25 by Caldicott that belong to Sir Elton John and his husband, David Furnish that hang alongside works by Keith Haring, Damien Hirst and Philip Taaffe, among many others. Selections from their photography holdings, including three other works by Caldicott, are currently on view in the exhibition “Fragile Beauty: Photographs from the Sir Elton John and David Furnish Collection,” at the V&A in London. London’s IdeelArt is currently offering limited editions of the C-print.

The couple’s collection has also included the work of fashion photographers Herb Ritts, Irving Penn and Horst P. Horst; stellar examples of photojournalism; Robert Mapplethorpe’s striking self-portraits; and Nan Goldin’s raw images of the downtown New York scene. Caldicott, with his abstractions, might feel like a bit of an anomaly, but what John values, in particular, is the magic of Caldicott’s analog process. “Richard has the unique ability to transform the medium of photography, creating something new but still using the most traditional technique,” he wrote in a forward to a Caldicott exhibition catalogue in 2005.

There is no digital trickery involved here. Caldicott, who lives and works in London, achieved his luminous, colorful Tupperware compositions by photographing the containers, developing the film and then layering the transparencies on colored grounds, so that when light passed through them during the printing process there was a “double intensity of color,” explains Christelle Thomas, of IdeelArt.

The interdisciplinary Caldicott came to photography through painting and drawing. Untitled #168 and similar works, with their precise arrangements of squares, call to mind the spare constructions, clean lines and precision of 1960s minimalism. The translucent, vibrant hues of his floating shapes hint at the saturated expanses of the Color Field painters, the spare architectural forms of Donald Judd, or even Josef Albers’s experiments in color theory in his “Homage to the Square” series.

But the question remains: How does an artist first find inspiration in Tupperware?

When it comes down to it, those storage containers are not so far off from the simple bottles, pitchers and other vessels that have inspired still-life painters. “He’d been working on a series of still-life photos for some time,” says Thomas, “humble objects, things that he thought were overlooked in the scheme of the genre, like brown paper bags, a white Tupperware lunch box.”

For some, the objects may call to mind the legendary mid-century Tupperware parties, where enterprising hostesses sold the brand’s latest products to other housewives, who shared homemaking tips. (Although the parties evolved over the years, they are largely a thing of the past, and Tupperware Brands Corp. recently filed for bankruptcy.) But that is not where Caldicott’s mind was. For him, says Thomas, “they had color, translucency and geometric forms that were in dialogue with photography, painting and sculpture.”

Nonetheless, images like Untitled #168 feel vaguely retro, summoning the promise of the Atomic Age with their almost radioactive glow.