Reform and renewal

A number of the movements for ecclesiastical reform that emerged in the 11th century attempted to sharpen the distinction between clerical and lay status. Most of these movements drew upon the older Christian ideas of spiritual renewal and reform, which were thought necessary because of the degenerative effects of the passage of time on fallen human nature. They also drew upon standards of monastic conduct, especially those regarding celibacy and devotional rigour, that had been articulated during the Carolingian period and were now extended to all clergy, regular (monks) and secular (priests). Virginity, long seen by Christian thinkers as an equivalent to martyrdom, was now required of all clergy. It has been argued that the requirement of celibacy was established to protect ecclesiastical property, which had greatly increased, from being alienated by the clergy or from becoming the basis of dynastic power. The doctrine of clerical celibacy and freedom from sexual pollution, the idea that the clergy should not be dependent on the laity, and the insistence on the libertas (“liberty”) of the church—the freedom to accomplish its divinely ordained mission without interference from any secular authority—became the basis of the reform movements that took shape during this period. Most of them originated in reforming monasteries in transalpine Europe, which cooperative lay patrons and supporters protected from predatory violence.

By the middle of the 11th century, the reform movements reached Rome itself, when the emperor Henry III intervened in a schism that involved three claimants to the papal throne. At the Synod of Sutri in 1046 he appointed a transalpine candidate of his own—Suidger, archbishop of Bamberg, who became Pope Clement II (1046–47)—and removed the papal office from the influence of the local Roman nobility, which had largely controlled it since the 10th century. A series of popes, including Leo IX (1049–54) and Urban II (1088–99), promoted what is known as Gregorian Reform, named for its most zealous proponent, Pope Gregory VII (1073–85). They urged reform throughout Europe by means of their official correspondence and their sponsorship of regional church councils. They also restructured the hierarchy, placing the papal office at the head of reform efforts and articulating a systematic claim to papal authority over clergy and, in very many matters, over laity as well.

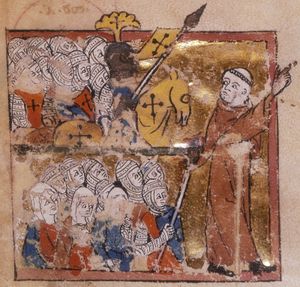

The emotional intensity of ecclesiastical reform led to outbursts of religious enthusiasm from both supporters and opponents. Many laypeople also enthusiastically supported reform; indeed, their support was a key factor in its ultimate success. The increase in lay piety on the side of reform was indicated by the events of 1095, when Urban II called on lay warriors to cease preying on the weak and on each other and to undertake the liberation of the Holy Land from its Muslim conquerors and occupiers. The enormous military expedition that captured Jerusalem in 1099 and established for a century the Latin kingdom of Jerusalem, an expedition only much later called the First Crusade, is as dramatic a sign as possible of the vitality and devotion of clerical and lay reformers.

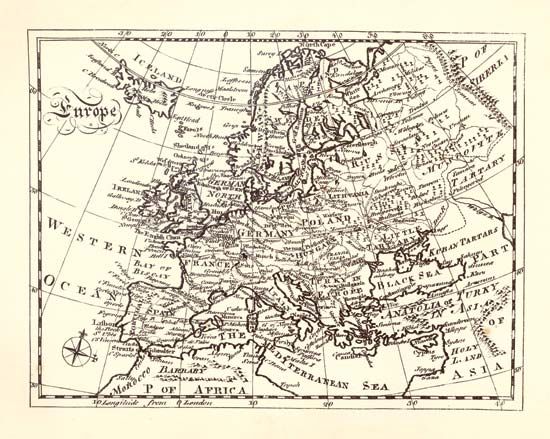

The First Crusade had other, unintended effects. The success of Genoa, Pisa, and other Italian maritime cities in supplying the Christian outposts in the Holy Land increased their already considerable wealth and political power, which were soon comparable to that of Venice. Proposals for later Crusades often led to searching analyses, not only of specific military, financial, and logistical requirements but also of the social reforms that such ventures would require in the kingdoms of Europe. Finally, by bringing Latin Christians other than pilgrims deeper into western Eurasia than they had ever been before, the Crusade movement led Europeans in the 12th century to a greater interest in distant parts of the world.

The reform movement had a pronounced effect on church and society. It produced an independent clerical order, hierarchically organized under the popes. The clergy claimed both a teaching authority (magisterium) and a disciplinary authority, based on theology and canon law, that defined orthodoxy and heterodoxy and regulated much of lay and all of clerical life. The clergy also expressed its authority through a series of energetic church councils, from the first Lateran Council in 1123 to the fourth Lateran Council in 1215, and greatly enhanced both the ritual and legal authority of the popes.

The reform movement also erupted in a violent conflict, known as the Investiture Controversy, between Gregory VII and the emperor Henry IV (reigned 1056–1105/06). In this struggle the pope claimed extraordinary authority to correct the emperor; he twice declared the emperor deposed before Henry forced him to flee Rome to Salerno, where he died in exile. Despite Gregory’s apparent defeat, the conflicts undermined imperial claims to authority and shattered the Carolingian-Ottonian image of the emperor as the lay equal of the bishop of Rome, responsible for acting in worldly matters to protect the church. The emperor, like any other layman, was now subordinate to the moral discipline of churchmen.

Some later emperors, notably the members of the Hohenstaufen dynasty—including Frederick I Barbarossa (1152–90), his son Henry VI (1190–97), and his grandson Frederick II (1220–50)—reasserted modified claims for imperial authority and intervened in Italy with some success. But Barbarossa’s political ambitions were thwarted by the northern Italian cities of the Lombard League and the forces of Pope Alexander III at the Battle of Legnano in 1176. Both Henry VI and Frederick II, who had united the imperial and Lombard crowns and added to them that of the rich and powerful Norman kingdom of Sicily, were checked by similar resistance. Frederick himself was deposed by Pope Innocent IV in 1245. Succession disputes following Frederick’s death and that of his immediate successors led to the Great Interregnum of 1250–73, when no candidate received enough electoral votes to become emperor. The interregnum ended only with the election of the Habsburg ruler Rudolf I (1273–91), which resulted in the increasing provincialization of the imperial office in favour of Habsburg dynastic and territorial interests. In 1356 the Luxembourg emperor Charles IV (1316–78) issued the Golden Bull, which established the number of imperial electors at seven (three ecclesiastical and four lay princes) and articulated their powers.

Although the emperor possessed the most prestigious of all lay titles, the actual authority of his office was very limited. Both the Habsburgs and their rivals used the office to promote their dynastic self-interests until the Habsburg line ascended the throne permanently with the reign of Frederick III (1442–93), the last emperor to be crowned in Rome. The imperial office and title were abolished when Napoleon dissolved the Holy Roman Empire in 1806.