“That was a good sermon.”

I had just finished preaching a message on friendship from the Book of Proverbs, and I’d made the case that forging strong relationships is harder in today’s world than it was in biblical times. Ours is an era of rampant individualism, autonomy, and isolation in a way that the ancient world simply was not. So I appreciated Michael’s compliment, though I could tell there was a “but” coming.

Sure enough, he added, “But there’s a group of people who wouldn’t be able to relate to what you said.”

He proceeded to tell me about the Plain Community—Amish and Old Order Mennonites here in eastern Pennsylvania best known in the wider world for their buggies and clothing styles. I was aware of them already, of course, but over the next year, Michael’s words kept returning to me.

Reports of friendlessness were coming from every direction. I saw the surgeon general’s public health warning about loneliness. I read social psychologist Jonathan Haidt’s latest book about isolation and the anxiety it creates in today’s youth. I heard stories from people in my church about their difficulty making friends. And I began to wonder: What could we learn from the Plain Communities, from people who couldn’t relate to the experiences I saw everywhere?

Michael drove me out into the country to meet with two of his former colleagues. Joseph is an Amish man who runs a house for emotionally and mentally troubled Plain people, and Catherine is a Mennonite woman who works for a mental health clinic that serves the Plain Community. Amish and Mennonite families travel far and wide, even from other states, to find help at this clinic. Michael knows them because he’s a psychiatrist who specializes in helping Amish and Mennonite people.

It felt like I’d entered a bygone era as we pulled up to the clinic. Men were dressed in black suits, with long beards, and women had dresses and bonnets to match. A group gathered outside were talking and laughing in Pennsylvania Dutch while taking a break from their woodworking and other endeavors.

As we entered Joseph’s office, I was instantly drawn to a chart posted on his wall. It was a family tree, dating back ten generations. I’m accustomed to offices filled with diplomas, certificates, and credentials. But in this community, who you are matters a great deal more than what you’ve accomplished.

That was the first surprise. The second came after I introduced myself and my purpose. Michael answered with something I almost didn’t believe: “I have never once heard an Amish or Mennonite person complain about being lonely.”

Surely this was hyperbole. Or exaggeration. Or he didn’t know this tribe very well. I turned to Joseph and Catherine. “Is loneliness a problem in your communities?” They looked at each other and shook their heads. “No,” Joseph replied. “I’ve never heard anyone complain of loneliness.”

Even though their work puts them in contact with people actively struggling with mental and emotional health issues—more likely, perhaps, than the average Plain person to deal with loneliness—neither could remember any such concern. Other worries, of course. But not isolation.

For the next hour, I heard story after story of unparalleled community care. A couple would come in for marriage counseling, and half of their extended family would tag along. A patient would come for mental health treatment and bring along a dozen friends. Clinical meetings would last for hours because so many family members and friends would crowd the room, offering their insights and support.

For us “English people” (the term many Plain People use for those outside their communities), this might sound overwhelming. Intrusive. Nosy. But it is also a testament to the closeness of these families’ and friends’ relationships and their unfailing commitment to one another.

As our conversation continued, my understanding and appreciation for these communities’ rigorous rules grew. There is a logic here, as draconian as the restrictions may seem, and it is not only about separation from the world and its evils. It is also about fostering community. The rules make it hard to be isolated, autonomous, and independent. They require community members to work together, stay together, and bond together.

For instance, why is electricity prohibited in Old Order houses but allowed in their barns? Because lights in every bedroom create easy paths to retreat from the common-room fireplace where families want to gather.

Why do some groups permit scooters but not bicycles? Because one may easily bike into town and separate from peers for the day, but riding a scooter alone is less safe or convenient. It’s more natural to go in a pack.

Why are tractors equipped with steel tires rather than rubber? Because steel tires are illegal for use on main roads, making it impossible to ride into town solo.

Why is the dress code so strict? Because it forms a comradery. It facilitates a cohesiveness. The clothes, the hats, the suspenders, the bonnets—it all creates an identity. It all says, “You belong here.”

“I didn’t realize how individualistic we are,” Michael told me after we left, “until I started working with these people.”

Of course, it’s easy to imagine downsides to this way of life or even ways its structures could be subject to abuse. I’m not planning to join the Plain Community or give up electricity or change my wardrobe. And yes, I’ve also met with people who left Amish or Mennonite communities because they found the restrictions and togetherness to be overbearing.

But imagine a world in which loneliness is the exception, not the rule. Imagine showcasing a family tree of ten generations instead of announcements of individual achievement. Imagine a community in which you can say, “I belong here.”

We English people can move in that direction. We can make togetherness more likely and isolation less convenient by reordering our own ways of life with those goals in mind.

At the congregational level, we must not give up “meeting together, as some are in the habit of doing” (Heb. 10:25), but organize our lives to meet more often and more easily. We can commit to in-person worship every Sunday—and make that the bare minimum. We can adopt spiritual disciplines that are practiced together rather than alone. We can put in the risky work of initiating and reciprocating, forging deep friendships over arm’s-length acquaintances.

Within families, there is even more we can do. Many households have a “no phones at the dinner table” rule to foster conversation. One family I know banned video games on weeknights, and now their kids run outside to play with friends every day after school. A coworker of mine has an early Tuesday breakfast every week. She attends the breakfast religiously, choosing people over sleep. Our family decided not to install a TV in our living room. We made that the nicest room in the house and put the TV in the cold, outdated basement with old furniture. We still watch TV, but we’re more likely to choose to stay upstairs together by the fireplace, reading or playing board games.

By making isolation inconvenient and togetherness easier, we can fight the plague of loneliness. With some intentionality, we can exchange shallow autonomy for deep belonging. We can learn a thing or two about togetherness from fellow Christians in the Plain Community.

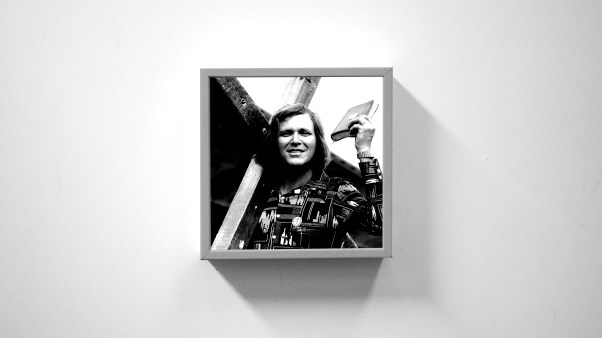

Nik Schatz serves as the executive pastor at Hershey Free Church in Hershey, Pennsylvania. He holds a ThM from Dallas Theological Seminary and a DMin from Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary.