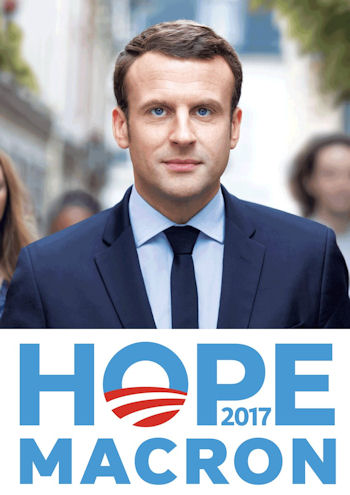

Emmanuel Macron

Polls opened in France at 8 am local time (6:00 UTC) for the second and final round of voting in presidential elections. The neoliberal former Economy Minister Emmanuel Macron faced the far-right National Front's Marine Le Pen on the runoff ballot. The last stretch of the dramatic campaign was marked by an insult-laden television debate and a 14.5 gigabyte leaked data dump from Macron's campaign that his En Marche! party has said included many fake documents to "create confusion."

Polls opened in France at 8 am local time (6:00 UTC) for the second and final round of voting in presidential elections. The neoliberal former Economy Minister Emmanuel Macron faced the far-right National Front's Marine Le Pen on the runoff ballot. The last stretch of the dramatic campaign was marked by an insult-laden television debate and a 14.5 gigabyte leaked data dump from Macron's campaign that his En Marche! party has said included many fake documents to "create confusion."

Macron was elected French president with an estimated 66.06% of the vote, while his rival, far-right Marine Le Pen, took 33.94%. In early returns, the French Interior Ministry reported that Macron won an estimated 65 percent of the vote, compared with Le Pen's nearly 35 percent. Le Pen called to congratulate Macron, and conceded defeat to a crowd of supporters in Paris. With polls closed across the country, Macron was elected French President with an estimated 65.8% of the vote, with his rival, far-right Marine Le Pen, taking 34.2%. Official turnout figures have been lower than in the April 23 first round. The noon turnout was 28.2%, slightly less than the 28.5% in the first round. At 5pm, the turnout was 65.3%, lower than the 69.4% at the same time on April 23.

The Elabe poll said that 64 percent of voters favored Emmanuel Macron on May 7, while a projection by Ifop Fiducial gave Macron 60 percent of the share. Macron had a 25-point margin in many opinion polls, but 57 percent of people who intend to vote for the banker-cum-politician would do so defensively, while a full 56 percent of likely Le Pen voters truly backed the far-right political scion.

French voters chose between the independent centrist former Economy Minister Emmanuel Macron, and far-right National Front leader Marine Le Pen after the field was narrowed down from 11 major candidates in the first vote on April 24. Polls projected that pro-Europe centrist Emmanuel Macron gained 23.7 % of the vote, and far-right populist Marine Le Pen got 21.7% of the vote. The two thus advanced from the first round of voting in France's presidential election to the winner-takes-all runoff on May 7.

France�s former economy minister Emmanuel Macron put his campaign for the 2017 presidential election into high gear at a vast rally in Paris on 11 December 2016, promising a �revolution� that will �pull France into the 21st century�. Organisers said the event at the Porte de Versailles exhibition centre in southern Paris had attracted at least 15,000 people, eclipsing last weekend's lacklustre gathering by the ruling Socialists when party grandees struggled to re-energise the faithful at a rally attended by a mere 2,500 supporters. The huge crowd of supporters, most of them in their 20s and 30s, cheered ecstatically as Macron promised an end to France�s �three decades of chronic unemployment�.

Macron has said that he is �neither on the left nor on the right� and that his policies are a �progressive� appeal to voters of all stripes who want France to be open, pro-European, market-friendly and, above all, not conservative. Declaring himself the �Candidate for Jobs�, Macron said his top priority was �liberating people through access to employment� and promising to further reduce France�s high employment taxes. He also promised to eliminate compulsory social security charges for unemployment and health insurance that come out of employees� pay cheques, which would add up to roughly �500 a year for workers on the minimum wage. Less revolutionary was his vow to keep the 35-hour working week.

The 38-year-old former investment banker was once a prot�g� of French President Fran�ois Hollande, who he served as economy minister until resigning in July 2016 after launching his own political movement �En Marche!� (�On the Move!� or �Forward!�). Macron was responsible for crafting many of Hollande�s business-friendly policies, and his efforts to deregulate France�s labour market have earned him praise from right-wing circles but lamentations from the left. However, he is likely to clash with conservatives over the hot-button issues of immigration, security and religion, which are likely to dominate the debate in the run-up to the April 2017 election.

French Economy Minister Emmanuel Macron on 07 April 2016 launched a new political movement he said would be neither of the left nor of the right, potentially shaking up the political landscape just a year before presidential elections. The initiative by one of the Socialist government�s most popular ministers fueled speculation that the former investment banker was laying the groundwork for grander political ambitions. The 38-year-old�s pitch for the middle ground also further muddies French political waters, where the rise of the far right National Front has left the mainstream parties along with their much older likely candidates with a reduced constituency to aim at.

Emmanuel Macron was born in December 1977 in Amiens. Macron is the son of doctors, Jean-Michel Macron, Professor of Neurology at the University of Picardy, and Fran�oise Macron-Nogu�s, MD. He wrote of his early life, " I was extremely close to my grandmother. She was principal of college. If my political reflection and commitment had only one origin, it would be her.... I grew up in an affluent environment. My years of childhood and adolescence have been synonymous with encounters, readings, discoveries. They prompted me a little later, during my studies, to go towards philosophy...

Emmanuel Macron was born in December 1977 in Amiens. Macron is the son of doctors, Jean-Michel Macron, Professor of Neurology at the University of Picardy, and Fran�oise Macron-Nogu�s, MD. He wrote of his early life, " I was extremely close to my grandmother. She was principal of college. If my political reflection and commitment had only one origin, it would be her.... I grew up in an affluent environment. My years of childhood and adolescence have been synonymous with encounters, readings, discoveries. They prompted me a little later, during my studies, to go towards philosophy...

"I consider that work is a value. Because it is the first source of individual emancipation and because it is the most powerful means of freeing oneself from determinism: it is through work that one can become one whom one envies... "

He is a haut fonctionnaire (senior public official) specialising in economic affairs. He studied philosophy and was Paul Ric�ur�s assistant for two years before attending the Ecole Nationale d�Administration (ENA) from where he graduated in 2004. The �cole nationale d'administration (ENA) is one of the most prestigious, elitist French grandes �coles, entrusted with the selection and initial training of senior French officials.

Macron then joined the Inspectorate General of Finance (IGF) and, in 2007, became expert adviser to the head of department. In this capacity, he served as rapporteur for the Commission pour la lib�ration de la croissance fran�aise (French Commission on Economic Growth), chaired by Jacques Attali. He then went to work in the banking industry. Between 2008 and 2012 Macron was employed at chez Rothschild and earned some 2.88 million Euros ($3 million)

In 2011, he was involved in Fran�ois Hollande�s campaign for the socialist party�s presidential primary and, subsequently, in the presidential campaign itself. During the latter campaign, he was tasked with coordinating a group of experts and with drawing up the candidate�s economic manifesto. In May 2012, he took up the position of Deputy Secretary General of the President�s Private Office with particular responsibility for monitoring strategy and economic affairs, and for overseeing fiscal, financial, tax and sector-based issues.

"France is sick", the new economy minister, Emmanuel Macron, was fond of repeating. Casting himself as doctor-in-chief during a press briefing on 10 December 2014, the 36-year-old former investment banker singled out "mistrust", "complexity" and "corporatism" as the "three diseases" he believes are stifling France�s economy. Since entering the goverment in late August 2014, Macron proved especially zealous, instantly becoming a fixture of French news reports. Le Monde described him as �being on the move at all cost, whether or not the exact direction is known�.

Even before his ministerial appointment, conservative daily Le Figaro ranked him number one in its list of �the 100 leaders of tomorrow�. Meanwhile, the gossip press dwelled on his marriage with his former high school teacher, Brigittte Trogneux, who is 20 years his senior. Macron attracted considerable attention abroad, with a lengthy profile in the New York Times describing the pro-business technocrat as the �face of France�s new socialism�. Macron's four-year spell at investment bank Rothschild, which made him a millionaire, has been widely noted � and hotly debated. Despite having joined the Socialist Party more than a decade ago, Macron is still nicknamed �the banker� both by far-right leader Marine Le Pen and left-wingers sceptical of his Socialist credentials.

Macron took office on 14 May 2017. Macron's popularity slumped less than three months since he took office. Macron, a former Rothschild banker whom critics have long accused of being a �friend of the rich�, stoked popular anger for doing away with a wealth tax in 2017 and proposing a rise in fuel taxes that campaigners said would hurt the poorest.

By early August 2017 Macron had slipped seven points, with just 36 percent of respondents having a positive view of the president who was elected on May 7. Forty-nine percent had a negative view, a rise of 13 points, according to the poll for the Huffington Post and the CNews TV channel. It confirmed a downward trend already shown by a previous poll, carried out by Ifop on July 17-22, which showed his popularity slipping 10 points in a month to 54 percent.

On 10 December 2018 Macron met with trade unions, employers� organisations and local elected officials, as well as Senate President G�rard Larcher and National Assembly President Richard Ferrand, as he tries to formulate a response to an unstructured Yellow Vest movement that had taken France by storm and broken through traditional political and trade union communication channels with the government. The upheaval in the Christmas shopping season dealt a heavy blow to retailing, tourism and manufacturing as road blocks disrupt supply chains.

Placating the disruptive protests that have rattled France was always going to be a hard sell for embattled President Emmanuel Macron. His long-awaited concessions on 10 December 2018 left most protesters dissatisfied and the broader public on the fence. In a solemn �address to the nation�, Macron sought to reassert control over a country wracked by four weeks of increasingly violent protests over fuel costs and an array of other grievances. His pitch included immediate relief measures aimed at struggling workers and pensioners, along with a rare act of contrition from a president often criticised as being out of touch.

Winning over some of the more moderate Yellow Vests may yet prove to be enough for Macron, who has enjoyed broad success in dividing and conqueringtrade unions when pushing through labor reforms. The 40-year-old president, whose popularity has plummeted in recent months, is keenly aware of the importance of public opinion in tackling protest movements. His performance � with 23 million viewers, a more popular draw than France�s winning World Cup final in July � went down better with the general public, according to early opinion polls. Just under half (49 percent) of people surveyed by the OpinionWay institute said they found Macron �convincing�, with between 60 percent and 78 percent approving his measures when taken one by one.

A green wave swept over France in local elections last Sunday, when Macron saw his young centrist party defeated in France�s biggest cities. That�s while Macron�s efforts to boost job creation have been swept away by the economic and social consequences of the country�s lockdown. A record abstention of almost 60 percent. They surmise it�s linked to exceptional circumstances � this second round was delayed by three months and people may still have been anxious about the coronavirus. The Greens built on gains made in the 2019 European elections to take control of some of the country�s biggest cities, including Marseille, Lyon, Strasbourg, Bordeaux and Poitiers. French Prime Minister �douard Philippe was elected mayor of the northern port city of Le Havre, a rare bright spot for President Emmanuel Macron on a day of nationwide municipal elections in which his party performed poorly.

Macron named senior civil servant Jean Castex � who coordinated France�s reopening strategy after almost two months of Covid-19 lockdown � the country�s new prime minister on 03 July 2020 as part of an expected cabinet reshuffle. The relatively low-profile Castex replaces �douard Philippe, who resigned earlier in the day as is expected before a government reshuffle. Macron is reshaping his government to focus on restarting the economy after months of lockdown and a poor showing for his party in local elections. Castex, 55, is a career civil servant who has worked with multiple governments, but is considered close to right-wing ex-President Nicolas Sarkozy, of whose presidential office he was deputy security general. The gradual reopening plan he spearheaded for Macron had been generally viewed as a success so far.

From the fight against climate change to the gender equality Macron touted as the "great cause" of his five-year mandate, Macron's term in office showed he could wax lyrical when it comes to the big issues. But in hindsight, the centrist leader's lofty speeches could also prove conspicuously short on follow-through.

Macron won office five years ago partly on the back of conservative rival Fran�ois Fillon's scandalous downfall. Les R�publicains candidate Fillon, a former prime minister and one-time frontrunner in the 2017 presidential race, saw his chances plummet after he was accused of corruption in a fake-jobs scheme involving his wife and public funds. Macron, who had never before been elected to public office before his meteoric rise to the �lys�e Palace, was able to present himself as a politician without any skeletons in his closet while condemning "practices from a bygone world". Macron was prodded by veteran centrist Fran�ois Bayrou � who conditioned his support for the political neophyte's fledgling party upon it � to pledge sweeping legislation meant to clean up politics.

Named justice minister under a freshly elected Macron, Bayrou himself was charged with drafting the new law. It proposed concrete reforms like banning parliamentarians from hiring family members, capping the number of consecutive terms one can serve, and monitoring lawmakers' expense accounts. But five years on, it bears noting that Macron's early golden rule of probity in politics had not always been respected in practice.

Bayrou and two fellow members of his centrist Modem party were obliged to leave the cabinet in June 2017, just a month after Macron's election, amid an inquiry into the party's use of parliamentary assistants in the European Parliament. The same fate befell Macron ally Richard Ferrand that same month over allegations in a separate private health insurance case. But the lofty principles were really left in tatters in 2018 after the Benalla Affair. That summer, Macron lashed out at the press and the justice system in defence of his longtime bodyguard Alexandre Benalla, who had been caught on film assaulting demonstrators during a May Day protest. From then on, the French president appeared to cast many of his pledges aside.

Ferrand, for one, was returned to the mix in September 2018, becoming speaker of the National Assembly. When he was placed under formal investigation a year later in the same private health insurance scandal that had seen him evicted from cabinet at the start of Macron's term, Ferrand was permitted to stay on in the prestigious post. (The case against him was finally dismissed in 2021.) G�rald Darmanin, for his part, was named interior minister in 2020, despite allegations against him by two women for rape and abuse of the vulnerable (a case also later dismissed). Justice Minister �ric Dupond-Moretti, meanwhile, was placed under formal investigation in 2021 over an illegal conflict of interest offence allegedly committed during his time in the job, but he was allowed to remain justice minister.

Macron was quick to grasp the public's weariness and distaste for politicians and traditional political parties. On the campaign trail in 2017, he promised to "do politics differently". It was a key factor in launching his rise to power, attracting armies of volunteers and activists to his En Marche (On the move) movement, drawn in by the prospect of building a political platform collaboratively. At that point, the idea was self-management at the local level, a lateral structure, shared decision-making and dialogue with opposition parties.

But over the course of Macron's term, and in particular during the Covid-19 pandemic, he in practice espoused top-down decision-making and wielded power vertically. France's parliament, and his party's majority lawmakers, mainly acted as a registry office for decisions handed down from above. Indeed, when the deputies freshly elected under Macron's La R�publique en Marche banner first took their seats in the lower-house National Assembly in 2017, they had to pledge not to oppose reforms. Furthermore, just like in that "bygone world" Macron once derided, the lawmakers had to commit to not supporting propositions tabled by the other groups in parliament.

Sometimes, the practice of power under Macron verged on the authoritarian. His controversial pension reform was forced through parliament without a vote in February 2020 (before the pandemic shelved its implementation). Law enforcement on his watch violently put down anti-government protests led by the Yellow Vest movement in 2018 and 2019, by one count seriously wounding 82 demonstrators, including 17 who lost an eye and four who lost a hand amid the unrest.

Macron also began his term with heady promises on environmental issues. After pledging to invest �15 billion in France's ecological transition and coaxing the environmentalist (and former TV star Nicolas Hulot) to join his cabinet to lead the battle, Macron used Donald Trump's June 2017 withdrawal from the Paris Climate Agreement to launch his own high-impact green appeal with a Trump paraphase: "Make Our Planet Great Again".

But the hope spurred by that early publicity coup soon gave way to disappointment as Macron ceded ground on a number of environmental commitments, rolling back his pledge to ban the herbicide glyphosate and the neonicotinoid insecticides harmful to bees, while implementing a Canada-EU trade deal (CETA) despite concerns over its environmental impact. Hulot would ultimately quit the cabinet in frustration in 2018, denouncing the "presence of lobbies in the circles of power" when he left. Macron came to power touting equality between men and women as one of the great causes of his term in office. But in practice, the issue hasn't appeared all that important, relegated as it was until 2020 to the responsibility of a junior ministry under the onus of the prime minister.

During a five-year term that coincided with the #MeToo movement globally, progress was made, nevertheless. Macron kept his promise to broaden legal access to medically assisted reproduction to single women and lesbian couples. Time limits for women seeking an abortion were extended from 12 to 14 weeks of pregnancy. And access to free contraception was broadened to girls under 15 in 2020 and women up to the age of 25 in 2022.

Meanwhile, salary equality in France remains dire. Despite the equality index established in 2018 to fight pay disparities, men are still being paid 30 percent more than women, according to the French statistics agency Insee. "Job insecurity, salary inequality at all levels, and raises for professions primarily occupied by women, including skilled ones like nurses, midwives and teachers, have been set aside," the economist Rachel Silvera told Alternatives �conomiques magazine.

The French President and his government struggled to deal with more turbulent lawmakers to pass laws since losing their absolute majority in parliament shortly after Macron was reelected for a second mandate in 2022.

In a surprise move, the French National Assembly voted 11 December 2023 to back a motion rejecting a controversial immigration bill on Monday without even debating it. The motion, proposed by the Greens, gained support not only from left-wing representatives but also from members of the right-wing Les R�publicains and the far-right National Rally. Macron�s government vowed to press ahead with the controversial immigration bill after this flagship reform was rejected by lawmakers in a humiliating setback. The political crisis heaped further pressure on a government that had struggled to pass reforms without a parliamentary majority.

The government�s stunning defeat in parliament prompted opposition politicians to call for its dissolution. Jordan Bardella, the president of Marine Le Pen�s National Rally, told BFMTV on Tuesday he was �ready to serve as prime minister�. The �lys�e, meanwhile, moved fast to try and stop the political fallout. After an emergency ministerial meeting on Tuesday, government spokesperson Olivier V�ran announced the formation of a special joint commission aimed at breaking the parliamentary gridlock �as fast as possible��. The commission will be composed of seven representatives from both houses of parliament and will aim to return the bill to both chambers for a vote, V�ran said.

The debacle in the National Assembly exposed the limitations of the politics of "en m�me temps" ("at the same time") � an approach pursued by Macron since 2017, combining policy solutions from both the right and the left wings of French politics. What was possible with an absolute majority during Macron�s first term is no longer feasible with a minority government. While the proposed law is widely perceived as right-leaning, it failed to satisfy both the right and far right, who reject providing work permits to undocumented workers. Simultaneously, it proved too repressive for the left, which opposes restrictions on family reunifications and the introduction of an annual debate on migration quotas. The balance is too difficult to find because this is typically the kind of issue where the contradictions of �Macronism� can surface.

Macron's decision to use executive powers to pass a contested increase in the pension age to 64 triggered weeks of violent protests. Prime Minister �lizabeth Borne found herself compelled to use Article 49.3 � a controversial provision in the French constitution that allows the executive to bypass the National Assembly to pass a law. Triggering Article 49.3 for the 21st time in only 18 months would raise the political stakes even higher, particularly after the administration's controversial use of it in the spring to pass pension reform occasioned protests and disruptive strikes across France that garnered the world�s attention.

Months of unrest and strikes over Macron's pension reform in the spring as well as five days of riots and looting in French cities, had fuelled calls among political opponents and some government insiders for a reshuffle. But with no clear candidate to replace Borne, a former technocrat who critics said lacked charisma but supporters said has delivered on many of Macron's campaign pledges already, the French leader decided to keep her at the helm of cabinet.

Borne resigned 08 January 2024, as President Emmanuel Macron sought to give a new impetus to his second mandate ahead of European parliament elections and the Paris Olympics this summer. The change in prime minister will not necessarily lead to a shift in political tack, but rather signal a desire to move beyond the pension and immigration reforms and focus on new priorities, including hitting full employment.

The government of French Prime Minister Michel Barnier fell 04 December 2024 to a no-confidence measure after the right-wing premier pushed an unpopular social security budget bill through parliament without a vote. Both the left-wing New Popular Front alliance and the far-right National Rally vowed to topple the government in response. Having been appointed by French President Emmanuel Macron in September 2024 in the belief that he was the one man who could survive a vote of no confidence in France�s deeply divided National Assembly, the right-wing premier was staring down a twofold threat � from the left-wing New Popular Front alliance, on the one hand, and the far-right National Rally (RN) party, upon which his fragile minority government depended.

There have been almost 150 no-confidence motions since the Fifth Republic was established in 1958. Prior to Wednesday, only one government had ever been ousted � Georges Pompidou�s, in October 1962. Michel Barnier was the first prime minister since 1962 to lose a no-confidence vote, as lawmakers on both the left and the right united to oust him. A no-confidence motion requires 288 votes in the National Assembly. Wednesday evening�s motion received 331 votes, with the left-wing New Popular Front (NPF) and the right-wing National Rally (RN) uniting in opposition to the minority cabinet imposed by President Emmanuel Macron. �I don�t consider it a victory,� RN�s Marine Le Pen told TF1 after the vote. �We made the choice we made to protect the French people.�

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|