The massive weight gain didn't make Michael "D'Angelo" Archer see the darkness that was looming. Neither did the hermit-like isolation, the shattered friendships, the years wasted without a new record in sight, or even the car accident that nearly killed him. By the time he careened off a lonely stretch of road near Richmond, Virginia, in September 2005, hitting a fence and rolling his Hummer three times, he'd already failed two stints in rehab—including one where his counselor was Bob Forrest, the guy on Celebrity Rehab with Dr. Drew. Bob had been cool, D'Angelo says, but his message of sobriety didn't take. "I went in under a fake name so people wouldn't know who I was, right?" D'Angelo tells me, in his first sit-down interview in twelve years. "So, you know, Michael never got treatment. It was this other character that was in there. And the moment I left, I went straight to the fucking liquor store."

Which helps explain why, months later, high on cocaine and drunk off his ass, D'Angelo found himself ejected from his car on that balmy Virginia night, hurtling through the pitch-blackness, flying. When he hit the ground, he broke all the ribs on his left side—and dealt another blow to his foundering career. Once he'd been the heir apparent to the giants of soul: Marvin, Stevie, Prince. (The rock critic Robert Christgau was so transported by D'Angelo's live show that he called him R&B Jesus.) But shortly after the wreck, discussions ended with several top music ecutives, including Clive Davis at J Records, who'd been considering signing him to a $3 million contract. Then D'Angelo's manager told him he was done with him, too.

Still, D'Angelo couldn't feel the bottom, even though it was right beneath him. He shows me how close, reaching toward the floor with his well-muscled left arm, the one inked with 23:4, for the Twenty-third Psalm. It's early March, just a few weeks after he's finished a sixteen-day mini-tour of Europe—his first live performances (not counting church) in more than a decade. We're sitting on a black leather couch in a Manhattan recording studio on Forty-eighth Street off Broadway, a quiet sanctum despite its proximity to the circus of Times Square. Through a bank of windows is the room where he has recorded many songs for his (very) long-awaited third album. Dressed in jeans and a white T-shirt, his hair in short tiny braids, D'Angelo looks good at 38—more solid than in his famously shirtless six-pack years, but clear-eyed and radiantly handsome. "I didn't really think I had a problem like that," he says, taking a hit off a Newport. "I felt like, you know, all I got to do is clean up and I'll be fine. Just get in the studio and I'll be fucking fine."

What finally made him see, he says, was the passing of J Dilla, the revered hip-hop producer, on February 10, 2006. They'd just talked on the phone, D'Angelo says, when suddenly, J Dilla was gone at 32 after a long battle with lupus. It was like a blinding light had been switched on. Why did so many black artists die so young? He'd been haunted by this thought for years. Marvin. Jimi. Biggie. "I felt like I was going to be next. I ain't bullshitting. I was scared then," he says, recalling how shame engulfed him, preventing him from attending the funeral. "I was so fucked-up, I couldn't go."

Shame, guilt, repentance—D'Angelo knows them well. To say that he was raised religious doesn't begin to capture it. He's the son and the grandson of Pentecostal preachers. To D'Angelo, good and evil are not abstract concepts but tangible forces he reckons with every day. In his life and in his music, he has always felt the tension between the sacred and the profane, the darkness and the light.

"You know what they say about Lucifer, right, before he was cast out?" D'Angelo asks me now. "Every angel has their specialty, and his was praise. They say that he could play every instrument with one finger and that the music was just awesome. And he was exceptionally beautiful, Lucifer—as an angel, he was."

But after he descended into hell, Lucifer was fearsome, he tells me. "There's forces that are going on that I don't think a lot of motherfuckers that make music today are aware of," he says. "It's deep. I've felt it. I've felt other forces pulling at me." He stubs out his cigarette and leans toward me, taking my hand. "This is a very powerful medium that we are involved in," he says gravely. "I learned at an early age that what we were doing in the choir was just as important as the preacher. It was a ministry in itself. We could stir the pot, you know? The stage is our pulpit, and you can use all of that energy and that music and the lights and the colors and the sound. But you know, you've got to be careful."

In 1995, when D'Angelo—or D, as he's known to his friends—released his platinum--selling debut album, Brown Sugar, he looked, on first impression, like the rappers of the time, with his cornrows, baggy jeans, and Timberland boots. But when he played and sang he instantly stood apart, a self-taught prodigy in touch with the ultimate muse. His groove hearkened to something purer, and whether crooning or caterwauling, he performed with fervor, like he was channeling the masters. A musician's musician, he played his own instruments, arranged and wrote his own songs. He was only 21 years old.

Many would rise to praise him—not just critics, but his peers. Common, who calls D "one of the most impactful artists of our day and age," remembers being in his car when "Lady" first came on the radio. "I was calling people and saying, 'Have you heard this?' " he says. George Clinton, the godfather of P-Funk, compares D's second album, Voodoo, to Gaye's groundbreaking What's Going On. And Eric Clapton's reaction to hearing Voodoo was captured on video. "I can't take much more," he says, reeling. "Is it all like this? My God!"

But for many, it was skin, not just music, that helped D cross over from R&B maestro to mainstream sex object. In 2000 he released the smoldering video for "Untitled (How Does It Feel?)," an instant sensation that made fans everywhere, especially women, lose their lustful minds. It's easy to find on YouTube: 26-year-old D'Angelo, naked from the hip bones up, staring straight into the camera, licking his lips and writhing in ecstasy. The video propelled him to superstardom—but it claimed its pound of flesh. D struggled mightily with the way his body threatened to overshadow his music. Then he all but disappeared.

"Black stardom is rough, dude," Chris Rock tells me when I reach him to talk about D. "I always say Tom Hanks is an amazing actor and Denzel Washington is a god to his people. If you're a black ballerina, you represent the race, and you have responsibilities that go beyond your art. How dare you just be excellent?"

After Brown Sugar went platinum, Rock put D'Angelo on The Chris Rock Show. Later, when D was mixing Voodoo, Rock hung out some in the studio. No surprise, then, that the first thing out of Rock's mouth after "Hello" is a joyful "He's back!" But he adds a sobering downbeat: "D'Angelo. Chris Tucker. Dave Chappelle. Lauryn Hill. They all hang out on the same island. The island of What Do We Do with All This Talent? It frustrates me."

I tell Rock that Ahmir "Questlove" Thompson, the drummer for the Roots and one of D's closest collaborators, has ticked off much the same list. Questlove has a theory about what happens to black genius—what he calls "a crazy psychological kind of stoppage that prevents them from following through. A sort of self-saboteur disorder." Rock says he understands.

For a black star, Rock says, "there's a lot of pressure just to be responsible for other people's lives—to be the E. F. Hutton of your crew. Everything you say is magnified. I mean, street smarts only help you on the streets. Or maybe occasionally they will help you in the boardroom, but boy, you wish you knew a little bit about accounting." There is pressure to be original but also pressure to be commercial, to make money, to succeed. Sometimes the two run at cross-purposes.

I ask Questlove what he thinks has held D back. He says it's not just the way "Untitled" turned D'Angelo into "the Naked Guy," though of course that didn't help. It's something bigger. "We noticed early that all of the geniuses we admired have had maybe a ten-year run before death or, you know, the Poconos," he says. "That renders D paralyzed. He said he fears the responsibility and the power that comes with it. But I think what he fears most is the isolation"—the kind that fame brings.

Questlove believes D's "eleven-year freeze" must end, not just for the artist's sake, but for the culture's. "I've told him: He is literally holding the oxygen supply that music lovers breathe," Questlove says. "At first, it was cute—'Oh, he's bashful.' But now he's, like, selfish. I'm like, 'Look, dude, we're starving.' When D starts singing, all is right with the world."

Michael Archer grew up not knowing Jesus' name. To some black Pentecostals, God is known as Yahweh and the son of God as Yahshua or Yahushua. "We would go to other churches and people would be saying 'Jesus,' " he recalls. "I was like, 'Who are they talking about?' " The piano, on the other hand, was something he understood innately. At 4, he taught himself to play Earth, Wind & Fire's "Boogie Wonderland."

When he was 5, his parents split, and the boys went to live with their father. "Mom was struggling," he says of his mother, then a legal secretary. Michael played the organ at his father's church and helped lead the choir. When he was 9, however, his dad "was battling his own demons," and the boys went to live with their mom for good. After that, "me and my father really didn't have much contact with each other."

In those years, Michael was drawn to his maternal grandfather's Refuge Assembly of Yahweh, up in the mountains outside Richmond. The region had been a hub of slave trading before the Civil War, with Richmond being a place where 300,000 Africans and their descendants were sold down the James River. Then and now, church was a place where loss could be mourned, pain salved. But what attracted Michael was the way fire and brimstone infused the music. In the temple, Michael saw his elder brother Rodney speak in tongues; he witnessed healings and exorcisms. At one Friday-night revival, he noticed a woman in a pew a few rows up. She was acting strange—tugging at her clothes, foaming at the mouth, ripping at the Bible. "She was possessed. E-vil," he says, breaking the word in two. "It was a long, hot, steamy night, and that demon disrupted it." He recalls his grandfather and the other ministers praying hard as the woman crawled on all fours, screamed, and ran outside to jump on the hoods of cars. "The demon was raising holy hell, and my grandfather came outside. He had big hands, and he didn't say a word. He just—" D'Angelo raises his palm to me—"and she falls out. That's it. End of story."

Already Michael was developing into the musical connoisseur that D'Angelo is today. His Uncle CC was a truck driver who moonlighted as a DJ, and he had a huge record collection. This was the beginning of what D now calls "going to school"—delving deep into jazz, soul, rock, and gospel history, from Mahalia Jackson to Band of Gypsys, from the Meters to Miles Davis to Donald Byrd, from Sam Cooke to Otis Redding, from Donny Hathaway to Curtis Mayfield to Sly Stone to Marvin Gaye. When Michael was 8, Gaye had just made a comeback with "Sexual Healing" and won two Grammys. "Everybody was talking about him," D'Angelo recalls. "Everybody." So just after Sunday sermon on April Fool's Day 1984, when Michael learned Gaye was dead at 44—shot by his own father—he was crushed.

That night, D'Angelo had the first of many dreams about Gaye. It was in black and white and took place at Hitsville U.S.A., Motown's Detroit headquarters. D was playing piano while a bunch of famous Motown stars milled about, waiting for Gaye. "When he finally showed up, he was young, very handsome, the thin Marvin. Clean-shaven. Very debonair," he told an interviewer back in 2000. "He came straight to me and shook my hand and looked me dead in the eyes, and he said, 'Very nice to meet you.' He grabbed my hand and wouldn't let go."

After that, whenever Gaye's music came on the radio, Michael felt a chill. The opening bars to "I Heard It Through the Grapevine" made him get up and leave the room. It was as if the power in Gaye's music had been linked, somehow, to his tragic end. "I would be petrified," he says—so petrified that his mother took him to a therapist. But the dreams of Gaye—himself a preacher's son—didn't go away until Michael turned 19. That was the year he changed his name to a moniker inspired by Michelangelo. That was also the year that his demo tape found its way into the hands of Gary Harris, then an A&R ecutive at EMI Music.

At their first meeting, D played a little Al Green on the piano and appeared to be just another "young kid with a lot of mystery." Earlier, Harris had seen a video taken at a talent show when D was 8. "He's playing the chords from 'Thriller,' and then he starts singing: It's close to midnight. Something evil's lurkin' in the dark. He was killing it," Harris recalls. "We used to call it 'getting the spirit' in church. He's the rarest of breeds: a genuine live attraction."

The church warned D'Angelo against secular music. "I got that speech so many times," he says. " 'Don't go do the devil's music,' blah blah blah." But his grandmother encouraged him to use his gifts as he saw fit. Not long after Harris signed him, D dreamed his last Marvin dream, this one in color. "I was following him as a grown man," he tells me. "He was a bit heavier, and he had the beard. He was naked, and all I could see was his back and that cap he used to wear all the time. And he got into this whirlpool Jacuzzi with his wife and his daughter and his little son, and that's when he turns around and looks at me. And he goes, 'I know you're wondering why you keep dreaming about me.' And I woke up."

Angie Stone, the soul diva who sang backup vocals on Brown Sugar, says that from the moment she met D, "I knew a superstar was on the rise." But "there was an innocence there that if we weren't careful was going to get trashed," adds Stone, who became romantically involved with D during that period and remains fiercely protective of him. "It's not a little bit of God in him. It's a lot of God in him. Sometimes when you have that much power, Satan works tenfold to break you."

As D'Angelo caught fire in the mid-'90s, the star-making machinery worked overtime to mold him into a bankable headliner. Stone remembers an event in Manhattan in September 1996 that was billed as Giorgio Armani's tribute to D'Angelo. Stone—thirteen years older than D—was three months pregnant with their son. They headed to the event together in a limo, but as they neared the venue where D was going to perform, it suddenly pulled over. "He was asked to get into another car, where he would be escorted by Vivica Fox," Stone says, her voice breaking slightly. The lissome Fox had just appeared with Will Smith in the blockbuster Independence Day. "It was a Hollywood moment. They wanted a trophy girl. I had to walk in behind them to flashing cameras. It started the wheels turning of what was yet to come."

The A-list was circling now, wanting a taste of D's authentic flavor. When Madonna turned 39, she asked him to sing "Happy Birthday" at her party. One press report had her sitting on his lap and French-kissing him. In fact, two sources say that ultimately D rebuffed her advances at another gathering not long after. At that event, the sources say, Madonna walked over and told a woman sitting next to D, "I think you're in my seat." The woman got up. Madonna sat down and told him, "I'd like to know what you're thinking." To which D replied, "I'm thinking you're rude."

But the lure of fame was constant, the temptations everywhere. While his label hoped for a quick follow-up album, D retreated, citing writer's block. He would later say that the birth of his first child, Michael Jr., got him back on track, but Voodoo—partially written with Stone—would be a full five years in the making. D fathered a daughter, now 12, with another woman, and has a third child, now almost 2.

Three weeks after its January 2000 debut, Voodoo hit No. 1 on the Billboard charts. Some early reviews were tepid (only later would Rolling Stone list it among its 500 best albums of all time), but it sold more than a million units in five weeks (and 700,000 since). The record would eventually win two Grammys, for best R&B album and best male R&B vocal performance for "Untitled." But as D began to fall apart, the video would be the only thing many fans remembered. "The video was the line of demarcation," says Harris. "It sent him spinning out of control."

Paul Hunter, the director hired to make the video, says his work was misunderstood: "Most people think the 'Untitled' video was about sex, but my direction was completely opposite of that. It was about his grandmother's cooking."

I've stopped by Hunter's office in Culver City, California, to hear how D'Angelo came to be filmed bare-chested (but for a gold cross on a chain around his neck), wearing only a pair of precariously low-slung pajama bottoms, looking like a wolf circling a bitch in heat. Illuminated from every angle, he spins very slowly as the camera fetishizes his every ripple and drop of sweat. I've imagined a lot of things that inspired the song's rousing lyrics (Love to make you wet / In between your thighs cause / I love when it comes inside of you), but collard greens weren't among them. Hunter is quick to explain that he, like D, was raised in the Pentecostal church.

"When I used to sing in the choir," Hunter says, "after the rehearsal, you go in to eat. I remembered seeing the preacher looking at a lady's skirt one week and then, the next Sunday, talking about how fornication is wrong." Such mid messages about the pleasures of the flesh were intertwined with the pleasures of the palate—part of the same sensual stew. "So I was like, 'Think of your grandmother's greens, how it smelled in the kitchen. What did the yams and fried chicken taste like? That's what I want you to express.' "

The video was the brainchild of co-director Dominique Trenier, D's manager, whose goal—some still see it as a stroke of genius—was to turn his client into a sex god. D'Angelo had been working hard with his trainer and was cut down to muscle and bone. Never in his life had D been this taut and virile, and Trenier seized the opportunity to create a true crossover artist without losing his loyal base. Initially, Hunter says, to capture the heat they were hoping for, "we were going to build sort of a box for a girl to come and mess with him. We all said, 'Well, how can we push it?' "

But when the shoot began at a New York City soundstage, the fluffer turned out to be unnecessary. D's memory was all he needed to bring it home. The video may have looked like foreplay, but it was actually about family, Hunter insists—about intimacy. Later, when I tell D'Angelo this, he says, "It's so true: We talked about the Holy Ghost and the church before that take. The veil is the nudity and the sexuality. But what they're really getting is the spirit."

The shoot took six hours, and it changed D's life. Trenier got his wish: Thanks to D'Angelo's luscious physicality, albums started flying off the shelves. But the trouble began right away, at the start of the Voodoo tour in L.A. "It was a week of warm-up gigs at House of Blues just to kick off the tour, draw some attention, break in the band," says Alan Leeds, D's tour manager then and now. "And from the beginning, it's 'Take it off!' "

Questlove, the tour's bandleader, was alarmed. "We thought, okay, we're going to build the perfect art machine, and people are going to love and appreciate it," he says. "And then by mid-tour it just became, what can we do to stop the 'Take it off' stuff?"

D'Angelo felt tortured, Questlove says, by the pressure to give the audience what it wanted. Worried that he didn't look as cut as he did in the video, he'd delay shows to do stomach crunches. He'd often give in, peeling off his shirt, but he resented being reduced to that. Wasn't he an artist? Couldn't the audience hear the power of his music and value him for that? He would explode, Questlove recalls, and throw things. Sometimes he'd have to be coad not to cancel shows altogether.

When I ask D about this, he downplays his suffering. Watching him pull hard on another Newport, I realize that he finds it far easier to confess his addictions than his insecurities about his corporeal self. Self-destructing with a coke spoon—while ill-advised—has a badass edge. Fretting over what Questlove has called "some Kate Moss shit" seems anything but manly. If given the chance, he tells me, he would absolutely shoot the video again. But he does admit to feeling angry during the Voodoo tour.

"One time I got mad when a female threw money at me onstage, and that made me feel fucked-up, and I threw the money back at her," he says. "I was like, 'I'm not a stripper.' " He was beginning to sense a darkness beckoning. He recalls a particular moment onstage at the North Sea Jazz festival in 2000. The band was in the middle of "Devil's Pie," his song about the spell fame casts upon the weak—Who am I to justify / All the evil in our eye / When I myself feel the high / From all that I despise—when he felt an ominous presence in the crowd. "That night I felt something that was like, whoa," he tells me. E-vil.

On the last day of the eight-month tour, Questlove says D'Angelo told him, "Yo, man, I cannot wait until this fucking tour is over. I'm going to go in the woods, drink some hooch, grow a beard, and get fat." Questlove thought he was joking. "I was like, 'You're a funny guy.' And then it started to happen. That's how much he wanted to distance himself."

While the tour was a success, both critically and commercially, it left D broken. "When I got back home, yeah, it wasn't that easy to just be," he says. "I think that's the thing that got me in a lot of trouble: me trying to just be Michael, the regular old me from back in the day, and me fighting that whole sex-symbol thing. You know: 'Hey, I ain't D'Angelo today. I'm just plain old Mike, and I just want to hang out with my boys and do what we used to do.' But, damn, those days are fucking gone."

Upon his return to Richmond after the Voodoo tour, D stepped into what he calls "an avalanche of shit." First he lost a few people who were close to him, including his Uncle CC, whose record collection had been the bedrock of D's musical education, and his beloved grandmother. After that, "I just kind of sunk into this thing."

It's not that D wasn't working, exactly. "I was in the studio," he says. "But I was also partying a lot. A little too much." He liked cocaine, he says, "because I could be a bit of an antisocial. It made me really open up and talk." But the problem with doing coke, he says, is "you can drink like a fish and it don't bother you. It was good in the beginning, but it got out of hand." For the first time, he says, "people started to go, 'Yo, man, you've got to get it together.' "

Excutives at his then label, Virgin, were exasperated. Momentum is money in the music business, and D was squandering his. Sometime in the mid-2000s, Virgin and D'Angelo parted ways. Then D had a falling out with Questlove, who'd played a track off the album-in-progress on an Australian radio station—a cardinal sin in D's eyes. Things had begun to unravel. In January 2005 a bloated, bleary-eyed D'Angelo was arrested in Richmond and charged with possession of cocaine and marijuana and driving while intoxicated. Trenier, horrified by the mug shot that appeared in press accounts, drove from New York City to Richmond to pick D up—then drove him to California so D wouldn't have to be seen in public in an airport. Soon, D was in rehab at the Pasadena Recovery Center. But he wasn't listening.

The near fatal Hummer accident came in mid-September of that year, after D had received a three-year suspended sentence on the cocaine charge. Still, he didn't think he'd bottomed out. Only five or six months later, after J Dilla's passing, would D finally reach out to Gary Harris, the man who'd first signed him. D told Harris he wanted to talk to Clapton, with whom he'd performed a few times. Harris tracked down a number. "I was like, 'Yo, I need some help,' " D recalls telling Clapton, who founded the Crossroads treatment center in Antigua. D would be welcome there, Clapton said, but it would cost $40,000. Harris called a former boss of his: Irving Azoff, the famed personal manager, who didn't know D but knew his work. Harris says Azoff agreed to cut a check.

Getting D to Antigua was an odyssey in itself. First off, he had neither a driver's license nor a passport—a challenge when trying to board an international flight. Second, while he'd begged for this intervention, his commitment to it wad and waned. When Harris first arrived at D's Richmond mini-mansion on a Sunday in late April 2006, the kitchen was littered with empty alcohol bottles, and D was a mess. "What should have taken a day took four days," Harris says, recounting their journey from Richmond to Charlotte to Puerto Rico, where "it took me two days to get him out of the hotel." Even once D was admitted to Crossroads, Harris says, "he was calling everybody he knew to get a ticket out." At his first two rehab centers, D had been able to evade and outsmart the counselors. At Crossroads, he was forced to deal. "It was like sobriety boot camp," he says. "They are up in your shit."

After his month in Antigua, it still took eighteen months for D to ink a new deal, this one with J Records (which would become RCA) in late 2007. But even then, in D's world, nothing happens quickly.

Everyone around him knows about D-time, a pace so slow that it could test even the most patient saint. Over the next few years, there were creative stops and starts. There were also setbacks. On March 6, 2010, D was arrested and charged with solicitation after offering a female undercover police officer $40 for a blow job in Manhattan's West Village. He reportedly had $12,000 in cash in his Range Rover. Asked to explain, he says, "It was just me making a stupid decision, a wrong turn, on the wrong night." He adds, "I'm not the role-model motherfucker. Look at all the shit that I've been in."

Questlove and D were back in touch now, but the drummer admits he kept D'Angelo at arm's length. For a while it seemed they'd only talk after someone died. Michael Jackson's passing had them on the phone in 2009. Then, in 2011, just hours after Questlove missed a call from Amy Winehouse on Skype, she, too, exited the stage. "D's the first person I called," Questlove recalls. "And I was just honest, like, 'Look, man, I'm sorry. I know you're thinking I'm avoiding you like the plague.' I just said plain and simple, 'Man, there was a period in which it seemed like you were hell-bent on following the footsteps of our idols, and the one thing you have yet to follow them in was death.' " He told D that if he'd gotten that news, it would have destroyed him. "That was probably the most emotional man-to-man talk that D and I had ever had."

Such honesty was only possible, Questlove says, because D'Angelo was finally getting his act together. He'd kicked his bad habits—well, most of them. "Any person who's dealt with substance abuse, it's an ongoing thing," D tells me. "That's the mantra—one day at a time—right? So you're going to have good days and bad days, but for the most part, I have a grip on it." He feels the forces of good are on his side now. "I don't know why it didn't happen sooner. It's just the way Yahweh ordained it."

His newfound discipline is evident in the way he has thrown himself into studying a new instrument, practicing for five and six hours a day. "The one benefit of this eleven-year sabbatical was he used 10,000 Gladwellian hours to master the guitar," says Questlove, who compares D to Frank Zappa. "He can play the shit out of it, and I don't mean no Lil Wayne shit."

Alan Leeds, the tour manager, senses a conscious decision on D's part to push beyond the beefcake. "I wonder if that isn't partially a way to take the attention away from that Chippendales shit, because when you're standing up playing guitar, there's a little less attention to what you're wearing and whether it's on or off and having to choreograph your moves," says Leeds, who's previously worked with James Brown and Prince. "It prevents you from having to calculate that shit."

Still, D is back in the gym, and it's not just vanity that's tugging at him. He knows physical presence is key to any live performance. And though he's still finer than fine, with swagger to spare, he's no longer the chiseled Adonis from the "Untitled" video. Eating little more than fish and green apples, D's been working to trim down his five-foot-seven frame, which just a few months ago had topped 300 pounds. In January, on the eve of his European tour, his managers told me he still had another twenty-five pounds to go. Which is why when I boarded the plane for Sweden, I wasn't surprised to see D's personal trainer—Mark Jenkins, the same one who got him into underwear-model shape twelve years ago—a few rows up.

When you haven't been onstage in more than a decade, a lot of things go through your mind. For D, it boils down to a question: Is this really happening? Backstage in Stockholm, before he steps into the light, the rumble of his fans tells him the answer is yes. Fittingly, this venue is an old Pentecostal church. Packed into pews, where red leather-bound hymnals are stacked neatly for Sunday worship, the audience of 2,000 is excited to the point of near levitation. No one was sure D would show tonight, and in fact he almost didn't. He missed two flights before his managers finally delivered him to Newark airport. "He Got on the Plane. Praise Jesus," Tina Farris, his assistant tour manager, would blog later. "The knot in my stomach is slowly unraveling."

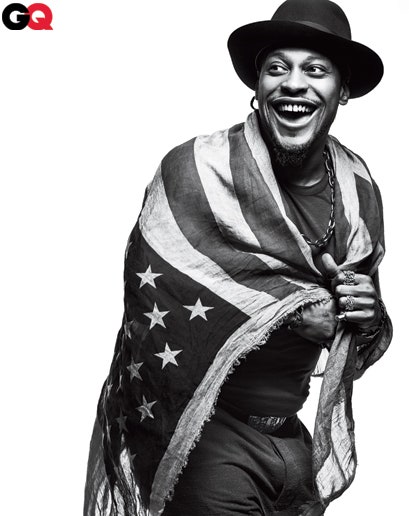

When he finally takes the stage ("In a minute!" he teases the audience from the wings. "In a minute!"), he sports a black leather trench coat that hits his black pants mid-thigh and a big-brimmed black hat. He calls this look Chocolate Rock. His hair is arranged in two-strand twists, and silver crosses hang on chains that bump against his chest. Also around his neck is the strap of his black custom Minarik Diablo guitar, named for its devilish horns.

He steps into the spotlight, the guitar slung low, his face aglow. If you could somehow access the voltage in the air, you could turn on all the lights in Scandinavia. First, the strains of an old song, "Playa Playa," cut through the din. Then a Roberta Flack cover—"Feel Like Makin' Love"—and then, seamlessly, a bluesy new tune, "Ain't That Easy," whose lyrics acknowledge, I've been away so long. The crowd catches the double meaning and roars as D peels off his jacket, revealing a black undershirt and sculpted arms. He glides through a mix of the old ("Chicken Grease," "Sht, Damn, Motherfcker," a cover of Parliament's "I've Been Watching You") and the new (the infectious "Sugah Daddy," and "The Charade," a battle cry that D says "is telling the powers that be, 'This is why we are justified in our stance' "). Is he rusty? A little. But his presence grows with each song.

At one point, he grabs the hem of his wife-beater with both hands and tugs it up—one, two!—in time with the song. The brief reveal of his midsection is a flashback to the trying days of 2000, but it's 2012 now, and the shirt stays on. When the band rips into its encore, "Brown Sugar," it feels like D has rounded third base and is about to slide to safety. "Good God!" D yelps, kicking the mike stand away, then catching it with his foot before it flies into the audience. "Give my testimony!" he shouts, blowing kisses from the stage.

The show is a triumph, and soon Twitter and Facebook are on fire. He's really back—no longer a specter. D's band—he can't decide on the name, but he's considering the Spades—radiates happiness and exhaustion as they load onto the tour buses, nicknamed the Amistad I and II after the slave ship. The next night he fills a 1,600-capacity club in Copenhagen, and afterward the buses leave on D-time—a full twelve hours behind schedule. By the time they arrive at the hotel in Paris on Sunday, January 29, sound check for that night's show is just three hours away. Still, despite having traveled 760 miles across Denmark, Germany, Belgium, and France, D and his trainer head directly to the tiny hotel gym. Coincidentally I'm there, too. I ask if D wants privacy. He does. As I head for the door, he steps wordlessly onto the treadmill, a weary man with many miles still to go.

But that night, at the tour's first 5,000-seat arena, Le Zénith, D'Angelo is revived. Toward the end of the show, after a medley featuring snippets of the melodious, bumping "Jonz in My Bonz" and the gospel-fueled "Higher," he hits a single percussive note on the piano that reverberates and fades away. Then he hits it again, and all of us in this cavernous hall begin to scream. It's the beginning of "Untitled," which he didn't perform in Stockholm or Copenhagen—which he hasn't played in public, not once, in a dozen years. After a few bars, D stops abruptly and stands up. The crowd cheers as he leans on one end of the piano, his chin in his hands, catching his breath. What happens next is the most soulful, palpable connection I've ever felt between an artist and an audience. As D sits back down and starts to play again, the audience spontaneously begins to sing. How does it feel?—four words coming from thousands of throats, urging him on. He responds gratefully, "Sing it again, sing it again." And they do, loudly, prettily, right on tempo: How does it feel? "Oh, baby, long time," he sings, "that this has been on my mind." People are crying, swaying, raising up their hands. I'm one of them. It's impossible not to be overcome as this sexy anthem, this source of so much pain, is transformed before us into a crucible of love. "Thank you so much," he says, his fingers fluttering on the keys as he brings it home. Then he stands up, kisses both his hands, and opens his arms to the crowd. The blue lights go dark.

I'm reminded of something Angie Stone says about D. "D'Angelo is always going to be D'Angelo," she tells me. "You can't take too much away from the gift itself. I'm sure there's still some fear there, because it's been a long time out of the spotlight. And when all the spotlight he'd got lately has been negative, there's a rebirth of some kind that needs to take place." God willing, we've all just witnessed it.

Upon D'Angelo's return to New York City in mid-February, his friends and colleagues began to worry a little. D-time speeds up for no man. Russell Elevado, D's longtime engineer, told MTV Hive that D wanted to finish his album "as soon as possible, but once he gets into the studio he gets into his own zone.... Altogether there's over fifty songs that he's cut since we started. I think he wants to put twelve songs on the album."

Questlove tells me the same thing. "To get five songs out of him, we had to throw away at least twelve that I would give my left arm for," he says. "I don't mind that, because I literally feel he is the last pure African-American artist left." Still, as weeks pass, Questlove admits, "My first fear was him not doing this at all. Now my new fear is, okay, the tour is over. Now what?"

For nearly a month, D mostly holes up in his apartment on the Upper West Side. Jenkins comes by regularly to sweat D in his private gym. He fasts for a few days, and the weight is coming off, but it seems D is headed back into his pre-tour cave. Only music persuades him to go out. Late in February, after he and D go to see Bjrk together, Questlove addresses a tweet to the Icelandic artist, saying, "amazing job last night. even d'angelo was mind blown & he leaves the house for NOBODY."

So when will he release his new album? D can't say for sure. His managers and his label are pushing hard for September, before the Grammy deadline. But nobody's banking on it. Sounding like a man who's all too familiar with D-time, Tom Corson, RCA's president and COO, says simply, "This year would be nice." In mid-April, D and his band are back in the studio, this time in Los Angeles, supposedly adding the final touches. But everything hinges on D letting the music go.

"I'm driven by the masters that came before me that I admire—the Yodas," D tells me, using the term he and Questlove have coined for their heroes. He tells me of a music teacher who told him that when classical composers like Beethoven made music, "people didn't understand it, and it got bad reviews," D says, recalling how his teacher said Beethoven responded: "He's like, 'I don't make music for you. I make music for the ages.' "

That's all well and good, Chris Rock says—as long as D actually releases his music. "You've got to earn it, man," he tells me, adding that the only reason fans aren't disappointed by Jeff Buckley, the celebrated singer-songwriter who recorded just one album, is that he drowned. "Body of work, babe. It's all body of work at the end of the day. I mean, the only way D's going to be a great artist with the output he has now is if he dies."

I can't help but think about J Dilla, whose death was the pivot, D says, on which his comeback began to turn. Dilla was the ultimate underground artist—prolific beyond compare, a legend in the hip-hop world. When he died, he'd made so much music with so many people—from De La Soul to Busta Rhymes to A Tribe Called Quest—that his legacy was secure. For all of D'Angelo's otherworldly talent, for all the passions he distills and reflects when he's in front of an audience, for all his perceived connections to Beethoven and Michelangelo and Marvin, and yes, to Jesus himself, the same cannot yet be said for him. Can Dilla, the overachiever, spur the underachiever to reach his true potential?

Back in the Times Square recording studio, I tell D I want to read to him something from a fan who posted recently on Prince.org, a site frequented by devotees of all things funky. The fan is worried by reports that D is trimming down, he writes, because of the havoc the "Untitled" video wrought: "While it's cool that dude is getting in better shape, I hope he's not trying to get back to the way other people picture him or want him to be. Dude just needs to get his head straight."

I look up from the page. "Is your head straight?" I ask.

"Straight," D'Angelo says, his eyes locked on mine. "Yes, my head is straight." Just because you're black, he adds, doesn't mean you have to look or sound a certain way, "or, you know, act ignorant or what have you, whatever the fucking gatekeepers have us doing because they think that that's the formula to make money. And a lot of motherfuckers, they just fall right into line." D has a term for artists like this: "minstrelsy." If he's learned nothing, he's learned this: He's no minstrel.

I ask him about Internet reports that the new album is called James River, after the Virginia waterway whose swampy banks provided hidden refuge for escaped slaves. No, that's no longer the title, D says, but he doesn't say what is. I let slip that I've heard about another new song he's written called "Back." I just want to go back, baby / Back to the way it was, it goes. And then: I know you're wondering where I've been / Wondering 'bout the shape I'm in / I hope it ain't my abdomen.

I tell him I'm impressed that he's addressing his body directly, using wry lyrics to confront and reclaim this difficult chapter of his life. He murmurs a thank you, but he looks a little unsettled. "Wow," he says, when I ask if the song will appear on the album. "I don't know if that's going to make it."

Later, when I reach Janis Gaye, Marvin's second wife—and a longtime D'Angelo fan—I tell her about the dreams D had of Marvin, and she isn't surprised. Her own children dreamed of Marvin on the night he was killed, and D is just a few years older. "Marvin is a protector, and I'm sure there was something in Marvin's spirit that saw something in D'Angelo's spirit," Janis says. I tell her about Rock's stern admonition that D needs to step it up, and she agrees. She even has a suggestion: "He should go to Marvin's Room, the studio that Marvin built," she says of the famed studio on Sunset Boulevard where Gaye recorded many of his hits. "Go in and take his fifty songs. Not to sound kooky or out there, but Marvin will help him to choose."

Amy Wallace is a GQ correspondent.