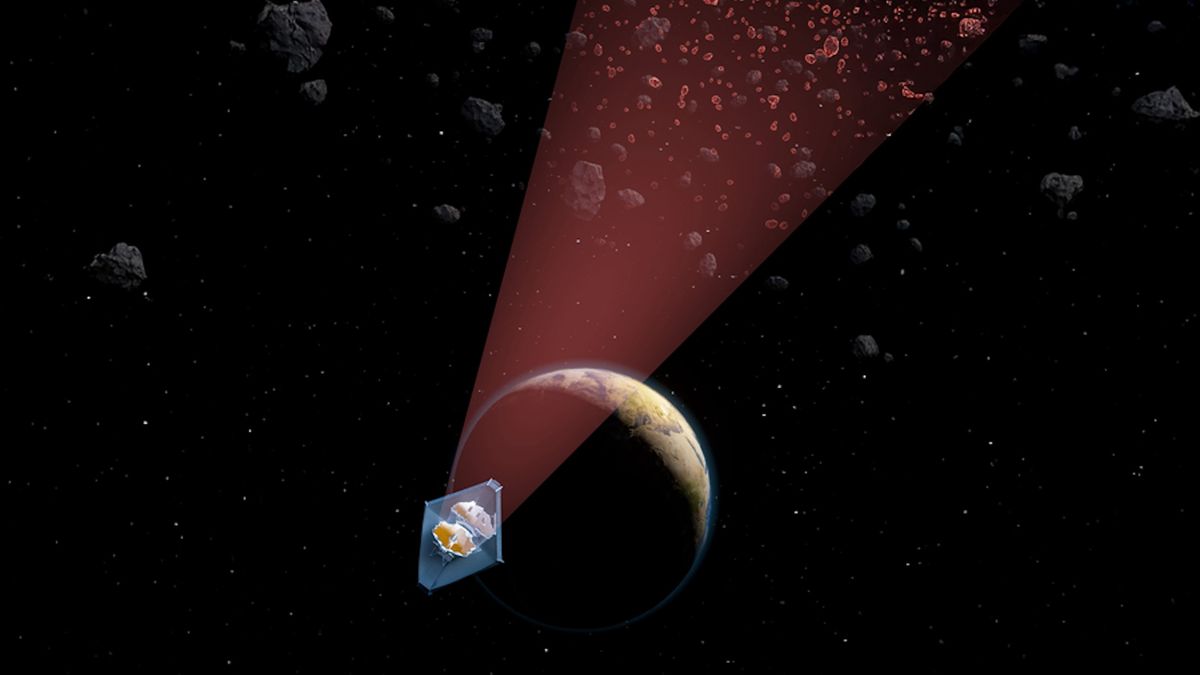

James Webb telescope spots more than 100 new asteroids between Jupiter and Mars — and some are heading toward Earth

Astronomers analyzing archival images from JWST have discovered an unexpectedly vast population of the smallest asteroids ever seen in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter.

Astronomers analyzing archival images from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have discovered an unexpectedly vast population of the smallest asteroids ever seen in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. The finding could lead to better tracking of the tiny but powerful space rocks that are likely to approach Earth.

The newfound asteroids range in size from that of a bus to several stadiums — tiny compared to the massive space rock that wiped out most dinosaurs, but they nevertheless pack a significant punch. Only a decade ago an asteroid just tens of meters in size took everyone by surprise when it exploded over Chelyabinsk, Russia, and released 30 times more energy than the atomic bomb detonated over Hiroshima in WWII.

These so-called "decameter" asteroids collide with Earth 10,000 times more frequently than their larger counterparts, but their small size makes it challenging for surveys to detect them well in advance.

In recent years, a team of astronomers including Julien de Wit, an associate professor of planetary science at MIT, has been testing a computationally-intensive method to identify passing asteroids in telescope images of faraway stars.

By applying this method to thousands of JWST images of the host star in about 40 light-years distant TRAPPIST-1 system, which is the best-studied planetary system beyond our own, the researchers found eight previously known and 138 new decameter asteroids in the main asteroid belt. Among them, six appear to have been gravitationally nudged by nearby planets into trajectories that will bring them close to Earth. An early, unedited release of the findings was published Dec. 9 in the journal Nature.

"We thought we would just detect a few new objects, but we detected so many more than expected — especially small ones," de Wit said in a statement. "It is a sign that we are probing a new population regime."

Fresh look at archival data

For the new study, de Wit and his colleagues compiled roughly 93 hours worth of JWST images of the TRAPPIST-1 system in order to enhance faint, fast-moving objects like asteroids above the background noise.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While such an approach rarely works for objects with unknown orbits, the team bypassed the limitation by using powerful graphics processing units (GPUs) to rapidly sift through large datasets, enabling a "fully blind search" across all possible directions to locate the newly-discovered asteroids, and then stacking those images.

Related: 'Spectacular' asteroid blazes over Siberia just hours after it was detected

"This is a totally new, unexplored space we are entering, thanks to modern technologies," study lead author Artem Burdanov, a research scientist in MIT's Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences department, said in the statement. "It's a good example of what we can do as a field when we look at the data differently — sometimes there's a big payoff, and this is one of them."

The newfound asteroids, which are remnants of collisions among bigger, kilometer-sized space rocks, are the tiniest yet to be detected in the main asteroid belt. JWST has proven to be ideal for the discovery, researchers say, thanks to the telescope's sharp infrared eyes that detect the asteroids' thermal emissions. These infrared emissions are much brighter than the faint sunlight reflected off the asteroids’ surfaces — the type of visible light that traditional surveys typically rely on.

Upcoming JWST observations will focus on 15 to 20 faraway stars for at least 500 hours, which could lead to the discovery of thousands more decameter asteroids in our solar system, according to the new study.

And newer telescopes will also help uncover thousands of small asteroids in our solar system. Chief among them is the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile — which, starting next year, will use the world's largest digital camera to photograph the southern sky every night for at least a decade, capturing images that each cover an area equivalent to 40 full moons. The high frequency and resolution are expected to detect up to 2.4 million asteroids — nearly double the current catalog — within its first six months.

"We now have a way of spotting these small asteroids when they are much farther away, so we can do more precise orbital tracking, which is key for planetary defense," said Burdanov.

Sharmila Kuthunur is a Seattle-based science journalist focusing on astronomy and space exploration. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Astronomy and Space.com, among other publications. She has earned a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social

Most Popular