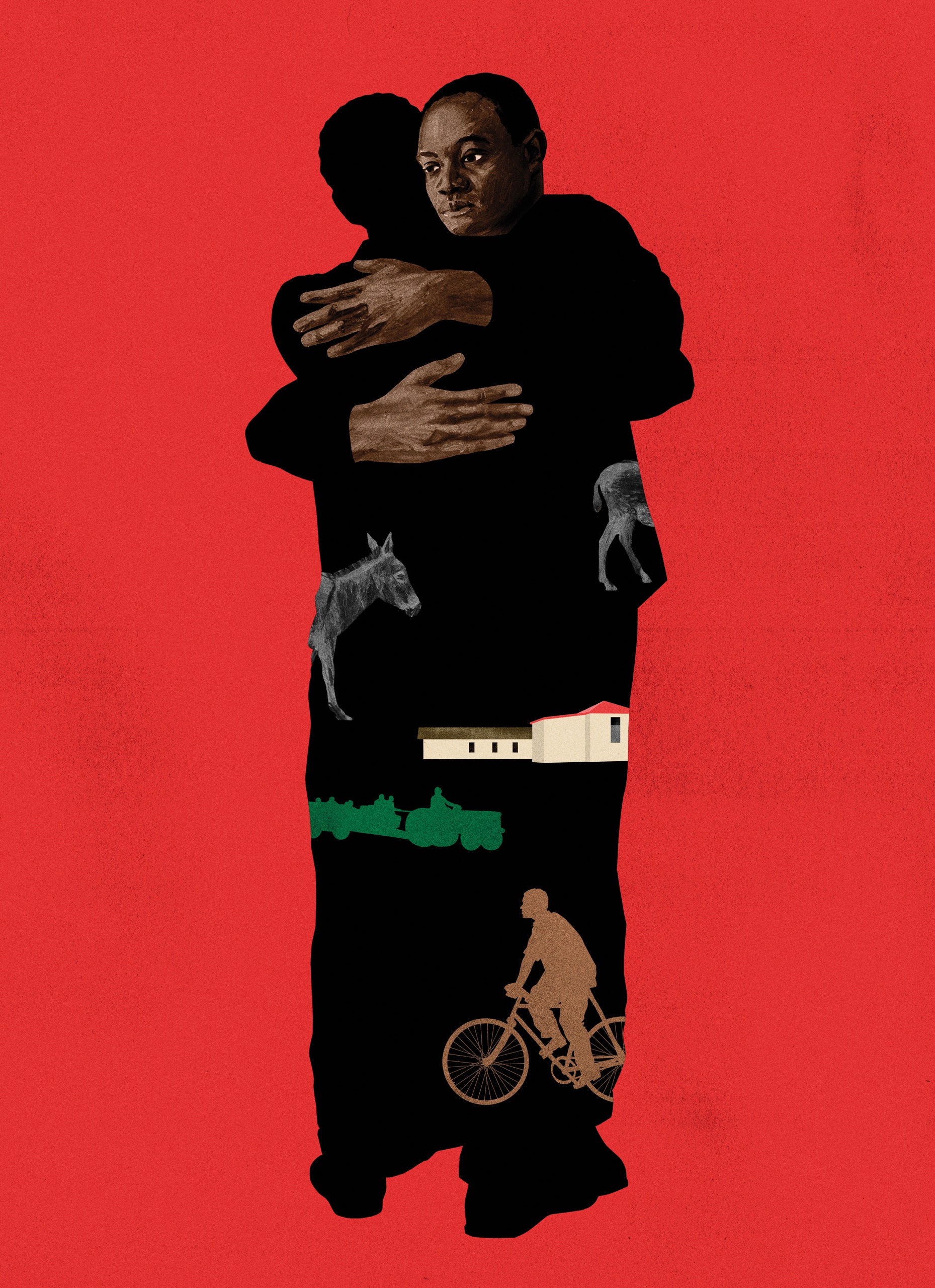

It’s harder to adapt a great book than an average one. Literary greatness often inhibits directors, who end up paying prudent homage to the source rather than engaging in the bold revisions that successful adaptations require. And even uninhibited directors may lack the stylistic originality of their literary heroes. It’s all the more remarkable, then, that the director RaMell Ross, in his first dramatic feature, “Nickel Boys”—adapted from Colson Whitehead’s Pulitzer-winning 2019 novel, “The Nickel Boys”—avoids both obstacles with a rare blend of daring and ingenuity. Few films have ever rendered a major work of fiction so innovatively yet so faithfully. In a year of audaciously accomplished movies, “Nickel Boys” stands out as different in kind. Ross, who co-wrote the script with Joslyn Barnes, achieves an advance in narrative form, one that singularly befits the movie’s subject—not just dramatically but historically and morally, too.

The movie’s title refers to Black youths (teens and younger) who are inmates of the Nickel Academy, a segregated and abusive “reform school” in rural northern Florida—particularly to two teen-agers, Elwood (Ethan Herisse) and Turner (Brandon Wilson), who become friends while incarcerated there, in the mid-nineteen-sixties. (The institution in Whitehead’s novel is inspired by the notorious Dozier School for Boys, but his characters are fictional.) Elwood, who is sixteen years old when he enters the facility, is being raised by his grandmother Hattie (Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor), who works on the cleaning staff of a hotel. He’s a star student, literary and politically passionate, in a segregated school. One of his teachers, Mr. Hill (Jimmie Fails), is a civil-rights activist, and he plays a Martin Luther King, Jr., speech on a record for his students. Elwood gets his picture in a local newspaper for participating in a civil-rights demonstration, but he’s only holding a sign; he longs to join in civil disobedience, but Hattie seems skeptical about the idea. Hitchhiking to a nearby college for advanced classes, he gets a ride from a flashily dressed, fast-talking Black man (Taraja Ramsess) whose car, unbeknownst to Elwood, is stolen. When the police pull the driver over, the innocent Elwood, too, is punished, resulting in his internment in Nickel.

From the start, Ross throws down a stylistic gauntlet: up until Elwood’s imprisonment, the action is seen entirely from his point of view—literally so, as if the camera were in the place occupied by his head, pivoting and tilting to show his shifting gaze, while his voice is heard offscreen. This device was famously used by Robert Montgomery in his 1947 adaptation of Raymond Chandler’s “The Lady in the Lake,” but it was no more than a gimmick. In Ross’s hands, the device becomes something overwhelmingly expressive: the images, rather than merely recording Elwood’s emotions, register the cause of those emotions and allow the viewer to partake in his inner world.

The results can be puckish, as when Elwood’s reflection appears in the chrome side of the iron that Hattie is sliding across an ironing board. But Ross’s technique is exquisitely responsive to the story’s depth and range of experience. The viewer shares Elwood’s naïve bewilderment when the driver of the stolen car, hearing a police siren, tells him not to turn around; similarly, one feels the anguished anticipation when Elwood awaits transport to Nickel. At this point, an extraordinary scene tears a hole in time, bringing the history of Black American life rushing in to overtake Elwood’s own: Hattie, with an air of unusual formality and seething indignation, recalls in excruciating detail her father’s death in police custody and her husband’s death at the hands of white assailants. But she expects better for Elwood.

Once the police have deposited Elwood in Nickel’s run-down barracks for Black inmates, Ross extends the dramatic force of his method while expanding its intellectual scope. At breakfast, Elwood meets Turner, who’s from Houston and much more streetwise. The impact of this moment is heralded in a coup de cinéma that is a vast amplification of the story: a repetition of the breakfast-table encounter, seen, the second time around, from Turner’s point of view. Once the pair become friends, both of their perspectives share the film, to mighty effect.

Elwood’s wrongful detention is only the first of the Job-like litany of injustices heaped upon him. In Nickel, sucker-punched and knocked out by a bigger kid, Elwood receives the same standard and brutal punishment as his assailant. Nickel’s sadistic supervisor, Mr. Spencer (Hamish Linklater), who is white, administers beatings with a strap in the so-called white house, far from the barracks. An industrial fan is used to drown out the victims’ screams, but it doesn’t quite do so, and Elwood, with his view of the horrors obstructed, hears them in terror while awaiting his turn.

Hospitalized as a result of the beating, Elwood gets a surprise visit from Turner, who’s also a patient (having skillfully feigned illness). Turner warns him that there are still worse punishments menacing the Nickel inmates, ranging from the sweat box—a brutally hot crawl space under a tar roof—to actual murder. (Such deaths were covered up by burial in unmarked graves and an official lie that the child ran away without a trace.) Elwood, inspired by the civil-rights movement and knowing that his grandmother has hired a lawyer, is confident that justice will prevail. He even keeps a notebook in which he records unpaid labor and which he thinks will help get Nickel shut down. Turner has no such confidence, insisting that no one gets out of Nickel alive except by getting himself out. The two teens’ visual perspectives, alternating through the hospital scene, embody their diametrically opposed views of American society, of their prospects, and of the destinies that await them.

Through Elwood’s and Turner’s eyes, in scenes that unfold in long and complex takes, the movie offers a formidable fullness of incident, intimately physical detail, and finely nuanced observations. The corruption of Nickel’s administrators and the legitimized absurdities of their cruel regime come to light as they’re experienced by the two teens, as do Hattie’s struggles to stay connected with Elwood and to seek legal relief. Lyrical snatches of daily life—passing moments of grace on a job outside Nickel’s grounds or during free moments in a rec room—are haunted by traces of past brutality and flickers of menace. Ross stages the action with a choreographic virtuosity that’s all the more astonishing given that this is his first dramatic film. (His previous feature, from 2018, is the documentary “Hale County This Morning, This Evening.”) His teeming visual imagination is matched by the agile physicality of Jomo Fray’s cinematography. As a first dramatic feature, “Nickel Boys” is in the exalted company of such films as Terrence Malick’s “Badlands” and Julie Dash’s “Daughters of the Dust.” Like them, it comprehensively creates a new way of capturing immediate experience cinematically, a new aesthetic for dramatizing history and memory.

Early on, the action is set in historical perspective by means of flash-forwards. Eventually, there are revelations about the atrocities at Nickel; the grounds are excavated, and human remains discovered. One of the friends (played as an adult by Daveed Diggs) gets wind of these investigations, having in the intervening years made his way to New York, found employment as a mover, and started his own business. In this later time frame, Ross continues to rely on point-of-view images, but with a piercing difference. The camera now floats just behind the character’s head, depicting work and home, love stories and painful reunions, fleeting observations and a reckoning with the past, as if from two points of view simultaneously—one visual and one spectral, bringing absence to life along with presence.

The onscreen incarnation of Elwood’s and Turner’s perceptions isn’t only intellectual or theoretical. The moral essence of Ross’s technique is to give cinematic form to the bearing of witness. Where Whitehead’s novel describes his characters’ physical torments in the third person, with psychological discernment and declarative precision, Ross’s movie fuses observation and sensation with its audiovisual style. It suggests a form of testimony beyond language, outside the reach of law and outside the historical record. It is a revelation of inner experience that starts with the body and all too often remains sealed off there and lost to time—except to the extent that the piece of art can conjure it into existence.

The movie’s twin aspects of witness and of point of view have a significance that extends beyond the drama and into cinematic history. There were no Black directors in Hollywood until the late sixties, and no Hollywood films that conveyed then what “Nickel Boys” shows in retrospect: the monstrous abuses of the Jim Crow era and its vestiges. In bringing the historical reckonings of Whitehead’s novel to the screen, Ross hints at an entire history of cinema that doesn’t exist—a bearing of witness that didn’t happen and the lives that were lost in that invisible silence. ♦