Where a person lives has a significant impact on their risk of dying from cancer, according to a new study from Imperial College London.

An analysis of the ten most likely cancers to cause death in men and women shows the considerable inequalities in cancer mortality rates across England. People with cancer in northern cities such as Newcastle and Manchester, as well as coastal areas to the East of London, have a higher risk of dying than cancer patients in other parts of the country.

The findings, published in The Lancet Oncology, suggest an urgent need for better access to cancer screening and diagnostic services nationwide.

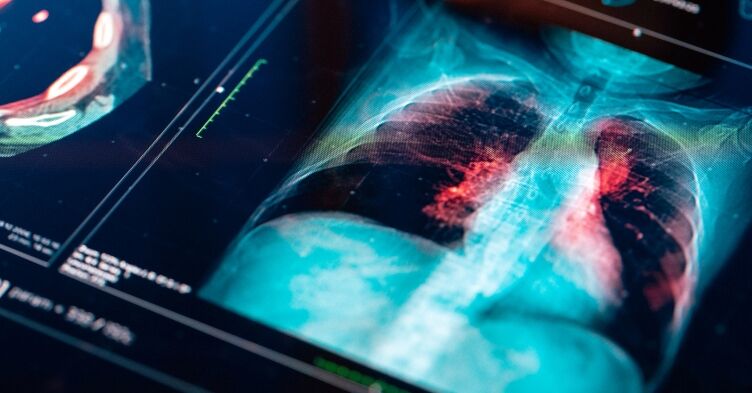

Cancer is now the leading cause of death in England, having overtaken cardiovascular diseases. The ten leading cancers for mortality for men are lung, prostate, colorectal, oesophageal, pancreatic, stomach, lymphoma and multiple myeloma, bladder, leukaemia and liver cancer. For women, it is lung, breast, colorectal, pancreatic, ovarian, lymphoma and multiple myeloma, oesophageal, leukaemia, cancer of the corpus uteri and stomach cancer. However, there is a lack of data on how the risk of dying from different cancers varies and how this has changed over the last 20 years.

Using death records, the researchers analysed the mortality rates for the ten forms of cancer with the highest death rates, looking at how the risk of dying from cancer in England has changed over 20 years, between 2002 to 2019, and how the rate varies across the 314 regions in England.

The team also analysed the link between cancer deaths and rates of poverty by looking at the proportion of people in the study who were claiming income-related benefits as a result of being out of work or having low earnings.

Over the twenty-year study period, the risk of dying from cancer before the age of 80 has declined for both sexes, from one in six to one in eight for women and from one in five to one in six for men.

However, some regions had a more significant decline than others, with districts in London achieving the largest reductions overall. In the Camden district of London, women have seen a 30 per cent decline in the risk of dying from cancer, compared to just a 6 per cent decline for the same period seen in the district of Tendring in Essex.

Professor Majid Ezzati, from Imperial College London, said: ‘Although our study brings the good news that the overall risk of dying from cancer has decreased across all English districts in the last 20 years, it also highlights the astounding inequality in cancer deaths in different districts around England.’

In 2019, the risk of dying from cancer before 80 years of age varied significantly across regions and ranged from one in 10 in Westminster to one in six in Manchester for women and from one in eight in Harrow to one in five in Manchester for men.

The risk of dying from cancer was found to be higher for both men and women in northern cities such as Liverpool, Manchester, Hull and Newcastle, and in coastal areas to the east of London and correlated with districts with more poverty and where levels of smoking, alcohol intake and obesity were high.

Professor Amanda Cross, from Imperial College London, said: ‘Access to cancer screening and diagnostic services which can prevent cancer or catch it early are key in reducing some of the inequalities our study highlights.’

She added: ‘Those who are more deprived are less likely to be able to access and engage with cancer screening. To change this, there needs to be investment into new ways to reach under-served groups, such as screening ‘pop-ups’ in local areas like supermarkets and working with community organisations and faith groups.’