The causes and symptoms of orthostatic hypotension, its connection to falls, and the importance of assessment through blood pressure monitoring

Abstract

Orthostatic hypotension occurs frequently in older people, particularly when they are in hospital or unwell. It can cause light-headedness, unsteadiness and falls. Nurses and care support staff should understand the physiology of orthostatic hypotension, and how to assess, monitor and treat it in relation to falls assessment and management. This second article in a two-part series on orthostatic hypotension focuses on how it contributes to falls, and how staff can identify and manage it.

Listen to this article by clicking here

Citation: Windsor J et al (2024) Orthostatic hypotension 2: effect of orthostatic hypotension on falls risk. Nursing Times [online]; 120: 12. This article is the updated version of Windsor J et al (2016) Orthostatic hypotension 1: effect of orthostatic hypotension on falls risk. Nursing Times; 112: 43/44, 11-13.

Authors: Julie Windsor is patient safety clinical lead – medical specialties/older people, NHS England. Mike Lowry is former lead for clinical skills and simulation; Sarah Ashelford is former lecturer in biosciences, both at School of Nursing and Healthcare, University of Bradford. Dr Julie Whitney is consultant practitioner in gerontology, King’s College Hospital, and lecturer in physiotherapy, King’s College London. Dr Sarah Howie is consultant geriatrician at St George’s Hospital.

- This article has been double-blind peer reviewed

- Scroll down to read the article or download a print-friendly PDF here (if the PDF fails to fully download please try again using a different browser)

- Read part 1 of this series here

Introduction

Falls are the most reported type of patient safety incident in acute and community hospitals, and the third most reported type of incident in mental health hospitals. Data submitted to the National Reporting and Learning System shows that ~250,000 falls were reported in 2015/16 across these three hospital settings (NHS Improvement, 2017). In 2022, the National Audit of Inpatient Falls reported 2,033 inpatient femoral fractures in England and Wales (Royal College of Physicians, 2023).

Falls have both a human and financial cost: for individual patients, the consequences range from distress and loss of confidence to injuries that can cause pain and suffering, loss of independence and, occasionally, death. Additionally, relatives and staff can often feel anxiety and guilt after a fall. The costs for healthcare providers can include additional treatment, increased lengths of stay, increased care costs on discharge, complaints and, in some cases, litigation. The estimated total yearly combined cost to hospitals of reported inpatient falls is ~£630m (NHS Improvement, 2017). In terms of non-hospital falls, the total cost to the UK of fragility fractures has been estimated at £4.4bn, which includes £1.1bn for social care and £2bn for hip fractures (Office for Health Improvement and Disparities, 2022; Public Health England, 2017).

Falls prevention is challenging. A careful balance must be struck between promoting safety and encouraging safe mobility to prevent complications of deconditioning, while supporting patient autonomy to make decisions about care, including risk taking and considerations of privacy and dignity. Although high-quality guidance is available from sources such as Montero-Odasso et al (2022) and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2013), evidence suggests that many organisations struggle to put evidence-based falls prevention activities into practice. Recent national audits have demonstrated that, although many organisations have falls prevention policies in place, improvements are needed in the association between what those policies include and the assessments and, importantly, interventions that patients actually receive (Royal College of Physicians (RCP), 2023).

Identifying patients at risk of falls

Factors associated with ageing that can increase falls risk include loss of muscle strength and balance, orthostatic hypotension, and visual and functional impairments. Older people may also have physical and mental health conditions that increase their risk of falls (Fernando et al, 2017).

Patients in hospital are at increased risk of falling, with pre-existing health problems compounded by acute illness, treatments, procedures and an unfamiliar environment (Oliver et al, 2010). Additionally, the prevalence of delirium in patients aged >65 years in acute general hospitals was found to be as high as one in three (NICE, 2010), making the falls prevention management of patients with impaired cognition and restlessness a challenge in all inpatient settings.

NICE (2013) has published guidance on falls risk factors, the effectiveness for interventions and prevention in hospitals. A key recommendation is that hospitals stop using falls risk prediction tools – which aim to calculate patients’ risk of falling (‘at risk/not at risk’ or ‘low/medium/high risk’) – due to their ineffectiveness in accurately discriminating between those with the potential to fall and those who will not fall. Instead, NICE and more recently the world falls guideline by Montero-Odasso et al (2022) advise that all patients and care home residents aged ≥65 years (and those aged 50-64 years, who are considered to be clinically at risk) are offered a comprehensive multifactorial falls assessment to prompt staff to identify and act on reversible fall risks and formulate personalised intervention plans. The falls assessment should promptly address identified individual risk factors for falling that can be treated, improved or managed (Box 1).

Box 1. Falls risk factors

- Sensory impairment, especially vision and hearing

- Cognitive impairment, especially delirium and dementia

- Falls history (causes, consequences and fear of falling)

- Gait disturbances, postural instability, mobility and/or balance problems

- Continence problems

- Footwear or foot ill health

- Health problems that affect falls risk, such as stroke and Parkinson’s disease

- Polypharmacy, plus falls risk inducing medications that increase the risk of falls, such as antihypertensives, diuretics, antidepressants, antipsychotics

- Orthostatic hypotension

The procedure to follow when taking a lying and standing blood pressure measurement is outlined in Box 2.

Box 2. Taking postural or lying and standing blood pressure

- Explain the procedure to the patient

- Ask the patient to lie as flat as possible for at least five minutes before measurement

- Measure BP and pulse rate while the patient is lying down

- Ask the patient to stand up, helping as necessary or using their normal mobility aid as required

- Ensure the patient remains close enough to the bedside to sit down safely and quickly should severe symptoms occur or they are unable to continue

- Measure BP and pulse rate immediately upon standing (or within one minute), then again at three minutes after standing

- If the BP is still dropping or symptoms persist (and patient can continue), repeat the BP reading

- Notice and document symptoms of dizziness, lightheadedness, vagueness, pallor, visual disturbance, increased postural sway, feelings of weakness (especially in legs), palpitations, shoulder or neck ache

- Safely assist the patient to sit down once procedure is complete

- Inform the medical team if there is a positive result. A positive result is:

- A drop in systolic BP of 20mmHg or more (with or without symptoms)

- A drop to <90mmHg systolic BP on standing, even if the drop is <20mmHg (with or without symptoms)

- A drop in diastolic BP of 10mmHg with symptoms (although clinically much less significant than a drop in systolic BP)

- Advise the patient of the results and, if orthostatic hypotension is suspected, of the immediate actions to prevent falls and/or unsteadiness

When carrying out the procedure, use a manual sphygmomanometer if possible. Automated sphygmomanometers may show repeated error messages. This may be due to the computerised algorithm that cannot overcome the dynamic readings associated with falling BP and/or irregular heart rate (Brignole et al, 2018).

BP = blood pressure.

Orthostatic hypotension

Orthostatic hypotension (OH) is an abnormal decrease in systolic blood pressure (BP) within three minutes of standing, and has been defined as:

- Systolic drop of >20mmHg or diastolic drop of >10mmHg and/or related symptoms;

- Decrease in systolic BP to <90mmHg (Brignole et al, 2018).

Prevalence

OH is a common disorder, particularly in older people. Studies have reported the prevalence of OH as nearly one in five in older persons living in the community, almost one in four in persons living in long-term residential care facilities, as high as 60% in patients with Parkinson’s disease and frequently occuring in hospital admissions (Saedon et al, 2020; Duggan et al, 2019; Velseboer et al, 2011).

A recent national audit – namely RCP (2023) – identified that, where an assessment had taken place (39% of patients), OH was identified in 28% of those who went on to fall and sustain a femoral fracture. It appears, therefore, that opportunities are being missed to identify and manage this common risk factor for falls in older hospitalised patients.

Causes and symptoms

Changing from a lying to standing position causes around 500ml of blood to pool in the lower extremities due to gravity. In a healthy person, this is counteracted by the autonomic nervous system via the baroreceptor reflex, which increases the heart rate, cardiac contractility and vascular tone, thereby regulating the BP to maintain adequate cerebral perfusion. Inadequate physiological response to such postural changes, especially in older people or, for example, in those subjected to periods of prolonged bed rest, can lead to an abnormally large drop in BP, resulting in symptoms that can increase the risk of falls. These symptoms normally resolve on returning to a seated or supine position.

Characteristic symptoms of OH include:

- Lightheadedness;

- Visual blurring;

- Dizziness;

- General weakness;

- Fatigue;

- Cognitive slowdown;

- Leg buckling;

- ‘Coathanger’ ache (in the shoulders and neck);

- Loss of consciousness.

These symptoms are indicative of inadequate perfusion of the brain. While patients remain conscious, these symptoms can be described as pre-syncope. In this circumstance, if the patient and staff are informed and able to anticipate these symptoms, preventative measures – such as sitting or lying the patient down – can be taken to avoid falls and injury.

Syncope is a transient loss of consciousness caused by inadequate perfusion of the brain. It is characterised by rapid onset, short duration and full spontaneous recovery when cerebral perfusion is restored (Brignole et al, 2018). Pre-syncope and syncope due to OH can cause falls with injuries. However, some older people do not experience or remember symptoms immediately beforehand, meaning that OH might be missed if not part of a structured assessment (Montero-Odasso, 2022; Brignole, 2018). Given that most hospital falls (80-90%) are reported as unwitnessed (National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA), 2007), there is no certainty as to their cause or whether they were related to BP unless it is looked for.

Decreased autonomic function associated with normal ageing can cause OH but, in hospitals, it is more commonly related to acute illness, dehydration and certain types of medications in common usage among older patients (Gibbons et al, 2010). Many different drug groups can cause OH, including antihypertensives, diuretics, antidepressants, antipsychotics and those used to treat Parkinson’s disease.

Normally a drop in BP on standing is regulated by a physiological response called the baroreceptor reflex (the first article in this series gives more detail on this). However, this response can be delayed in older patients or, for example, those with extensive periods of immobility who can be particularly prone to OH (NICE, 2015). A transient low BP can lead to dizziness, postural instability and even a momentary loss of consciousness, which makes these patient groups more prone to falls. However, OH may be asymptomatic in some people and, often, after a fall, they may be unable to recall preceding symptoms.

Other causes of OH are:

- Low intravascular volume (blood or plasma loss, fluid or electrolyte loss);

- Impaired cardiac function due to structural heart disease;

- Vasodilation due to use of ‘street drugs’ or alcohol.

Disorders such as dementia, multiple system atrophy or diabetic autonomic neuropathy are also often associated with OH.

Managing OH

To successfully manage OH, nurses should:

- Discuss a management/treatment strategy with the medical team and patient;

- Rectify dehydration as necessary, which may include increasing oral intake or, if this is not possible, intravenous fluids;

- Request a medication review to identify potential falls risk inducing drugs;

- Advise patients to avoid hurrying and remind them to use the call bell to get help to transfer/mobilise;

- Consider supervision/observation needs for patients who may not be able to remember to call for help;

- Advise patients when getting out of bed - particularly first thing in the morning or to go to the toilet at night - to safely sit on the edge of the bed with their legs hanging down and, if possible, feet firmly on the floor for a few moments before standing;

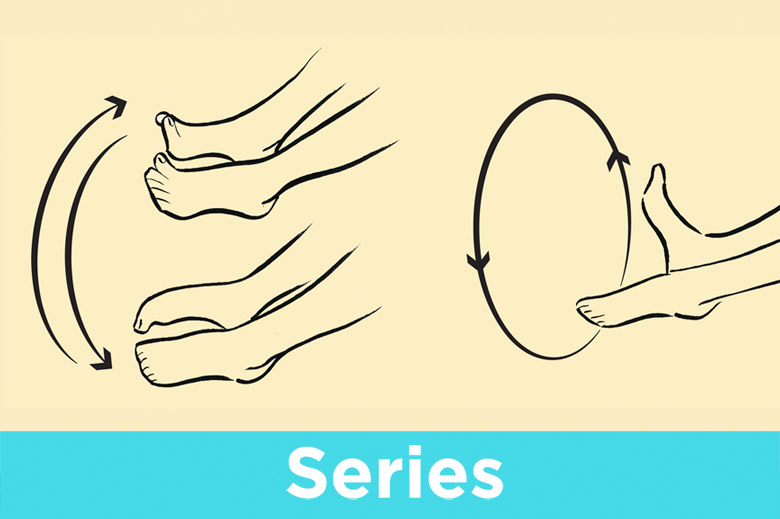

- Advise patients that, before rising from a chair or, once standing still, before moving away, they should perform leg exercises such as calf pump exercises (Fig 1) for a few moments;

- Advise patients to avoid situations that cause vasodilation that will lower BP, such as having very hot baths or showers, or getting overheated in a warm room;

- Discuss with the medical team whether other interventions – such as abdominal binders, bed head tilt or increased salt intake – may be appropriate;

- Avoid prolonged periods of flat-lying bedrest and immobility.

Conclusion

Falls may be avoided with increased attention to the influences of altered BP. Nurses, healthcare professionals and care support staff should take special care when patients are assessed to be at risk of falling. It is recommended that assessment for OH be incorporated into falls assessments, care plans and educational programmes for care staff. Opportunities should be created to discuss the risks and possible consequences from falling due to OH and how to take preventive measures.

● Part 1 details the anatomy and physiology of blood pressure, highlighting why its regulation is so important

Key points

- Know how orthostatic hypotension can contribute to falls risk

- Understand who is at risk of orthostatic hypotension

- Consider person-specific falls risks when developing interventional fall care plans

- Do not use falls risk prediction tools for inpatients

- Ensure all inpatients aged >65 years are offered a multifactorial falls risk assessment

Glossary

- Orthostatic hypotension (or postural hypotension) – a drop in blood pressure upon standing

- Fragility fractures – those that result from a fall from standing height or less

- Syncope – the transient loss of consciousness due to cerebral hypoperfusion

- Polypharmacy – the prescription of multiple medications

Brignole M et al (2018) ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope. European Heart Journal; 39: 21, 1883-1948.

Duggan E et al (2019) Admissions for orthostatic hypotension: an analysis of NHS England Hospital Episode Statistics data. BMJ Open; 9:e034087.

Fernando E et al (2017) Risk factors associated with falls in older adults with dementia: a systematic review. Physiotherapy Canada. 69: 2, 161-170.

Gibbons CH et al (2010) Pharmacological treatments of postural hypotension

(Protocol). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 1.

Montero-Odasso M et al (2022) World guidelines for falls prevention and management for older adults: a global initiative. Age and Ageing; 51: 9, afac205.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2015) Orthostatic Hypotension due to Autonomic Dysfunction: Midodrine. NICE.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2013) Falls in Older People: Assessing Risk and Prevention. NICE.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2010) Delirium: Diagnosis, Prevention and Management. NICE.

National Patient Safety Agency (2007) Slips, Trips and Falls in Hospital. NPSA.

NHS Improvement (2017) The Incidence and Costs of Inpatient falls in Hospitals. NHSI.

Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (2022) Falls: applying All Our Health. gov.uk, 22 February (accessed 20 June 2024).

Oliver D et al (2010) Preventing falls and fall-related injuries in hospitals. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine; 26: 4, 645-692.

Public Health England (2017) Falls and Fracture Consensus Statement: Supporting Commissioning for Prevention. PHE.

Royal College of Physicians (2023) The 2023 National Audit of Inpatient Falls (NAIF) Report on 2022 Clinical Data. RCP.

Royal College of Physicians (2015) National Audit of Inpatient Falls: Audit Report 2015. RCP.

Saedon NI et al (2020) The prevalence of orthostatic hypotension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A; 75: 1, 117–122.

Velseboer DC et al (2011) Prevalence of orthostatic hypotension in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Parkinsonism and Related Disorders; 17: 724–9.

Help Nursing Times improve

Help us better understand how you use our clinical articles, what you think about them and how you would improve them. Please complete our short survey.

Have your say

or a new account to join the discussion.