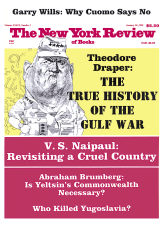

1.

Columbia Pictures began showing Andrei Konchalovsky’s The Inner Circle on the day the Kremlin struck the colors of Lenin’s flag and raised the tsar’s in its place. Lenin had proclaimed the end of God, Who survived, and now the Russians have decreed the end of the Devil, that old dog whose death-defying toughness is Konchalovsky’s theme.

His devil is Joseph Stalin and his hell is the Kremlin of the Thirties, whose corridors are as pristine, polished, and sparsely populated as the communal apartments in the Moscow it rules are worn, dingy, and cluttered with crowds.

It is history’s custom to identify Stalin’s Inner Circle as the Molotovs, the Berias, and the lesser planets gravitating around the sun of his authority. Konchalovsky has chosen instead to fix that collective on the servants of his household, those ordinary Russians who were his guards, his waitresses, and his film projectionist, and who were all of them worshipers and prisoners not of his tyranny but of his charm.

For, as Konchalovsky reminds us, “The devil always uses his power to seduce and not to force.” Thus Stalin “was very affectionate with simple people.” The Berias and the Molotovs were friends and it was his nature to be “afraid of them….” “On the other hand, he seems to have genuinely loved and respected his guards…who hadn’t been corrupted by politics.”

And so his servants adored Stalin as all simple Russians adored him. Charm is the ultimate refinement of Satan’s work.

“Spiritual tragedy occurs,” Konchalovsky decided, “when you realize that you have been seduced, because you are implicated in your own victimization…. And, in this sense, Stalin seduced the nation…. This seduction acquired a mass dimension, bordering on fanaticism, which is characteristic of Russians.”

Both The Inner Circle and the sweeping scenes around the Kremlin towers at this coinciding moment of real history leave us with the puzzle of whether the Russians yet realize their part in their own victimization. It is not yet clear whether they aren’t still convinced that it is better just to bury Stalin as though he and their infatuation with him had never been, that all they need to do is to be reborn as Adams and Eves in one more New Eden.

It can hardly be that simple; despotism’s devilish charms are not stuff so easy to inter. Ivan Sanshin, The Inner Circle’s protagonist, runs the movie projector for the KGB, the Soviet secret police. Then he is roused in the night by policemen, who bear themselves as their function ordains when they are about to arrest political suspects. Ivan is homo Sovieticus, which is to say that he regards the terror’s whims with panic and its rectitude with reverence. He takes it for granted that he is being transported to Lubyanka for the crime of having allowed a newsreel film to catch fire and dissolve Stalin’s face on the screen in full view of a KGB audience.

Instead he is carried to the Kremlin and ordered to a projection booth. The scent and countenance of the terror are sustained to the point where he is told that he is to project whatever film Stalin’s taste appoints. Shuddering with awe at the challenge, he hastens to work. Afterward Stalin comes upon him in the corridor and says, “You projected well.” Every other presence in the Kremlin incarnates the fearful; but Stalin’s only reminds of gently joshing fatherhood.

Ivan had always been a willing slave, but that encounter converted him into a loving one. A neighbor in the communal apartment is arrested one night, and his wife and small daughter taken away soon afterward. Ivan accepts their fate as the justice due proper enemies of the people. His own wife cannot stifle those feelings of the heart he rejects as impulses to treason. She traces the neighbor’s child to the state orphanage for relicts of the people’s enemies; the KGB finds out and sends Ivan home to revile her subversions and to quake before their mutual peril. But they are spared in part because the KGB has marked her beauty as spoil for Beria, their chief. Beria, Konchalovsky notes, “doesn’t rape her though he could have. He seduces her.”

After a year as his plaything, she comes back to Ivan, pregnant, hard-bitten, and harder-used, and, knowing her own complicity in her ruin, hangs herself. Ivan loves Stalin still.

The Inner Circle springs from Konchalovsky’s hope that it may “make Russians think about whether the sources of Stalinism are to be found inside themselves.” He has made the effort bravely, movingly, and without much confidence that any lesson, even his, can change the Russians, who once thought they could abolish God, now think they have disposed of the devil, and still seem to think that the past will have no future weight once everyone agrees to forget that it ever happened.

Advertisement

2.

Newmarket Press offers The Inner Circle, edited by Jamey Gambrell, as “The Companion to the Columbia Pictures Feature Film.” Most of the above reflections on Konchalovsky’s final product are drawn from that volume, and from his commentary on the thing intended, which, as so often, commands our attention more lastingly than the thing executed.

It seems to be rather easier to dispose of regimes than to cast away the habits they ingrain. R.H. Tawney once described Marx as “the last of the schoolmen” and Lenin was never so purely Marxist as when he proclaimed that “of all the arts, the cinema is the most important.” For Stalin, then, film had the same function as a Bible of the illiterate that the wall painting had for the medieval churches.

The mandate, with or without the impulse, to teach was the Soviet film maker’s controlling motive; and, determined though he is to repudiate that heritage, Konchalovsky cannot entirely escape it.

“Art,” he has decided, “offers an education in ethics more than politics.” Enlightened as it is, this insight still leaves us with the concept of art as a tool; and there are traces of the agitprop even in this exposition of agitprop’s dreadful consequences.

We might somehow find richer satisfactions, not to say transcendences, in The Inner Circle if it contained more complicated people than its Everymen and its Everywomen. It has just a few too many undiscarded residues of the technique of those cautionary tales whose lessons instruct us more about the outer life than involve us with the inner. The Inner Circle’s intention is nonetheless heroic, and its achievement admirable.

This Issue

January 30, 1992