This July has been the hottest in our recorded history and, most likely, over the last 120,000 years. Four “Heat Domes” across the northern hemisphere—over West Asia, North America, North Africa and Southern Europe—contributed to soaring temperatures, not just breaking but shattering records by several degrees. High up in the Andes, winter has turned to a blazing summer. The sun has been blotted out by Canada’s enormous fires.

Together with deadly heat came unprecedented rains and flooding, most notably in Delhi and Beijing. It’s not just the carbon cycle but the water cycle that’s been supercharged by fossil-fueled modernity. We should never have called it Earth; ours is an oceanic planet, and most of the extra heat is being absorbed by oceans now hotter than ever before. Their warmed currents have meant that a Mexico-sized chunk of Antarctica failed to refreeze this year.

Increased amounts of water vapor—itself a powerful greenhouse gas—caused by warming on Planet Ocean are in turn turbocharging the vast atmospheric heat engine, causing more extreme weather. Not for nothing has the UN Secretary General Antonio Gueterres declared a new era of “global boiling.” Look closely at the chart below: July is more than four standard deviations outside the 1979–2000 mean.

Amid the weather crises, other records have been smashed too: the most air travel passengers in a single day in the US; the highest-ever profits for European carriers IAG and Air France-KLM; record oil consumption and record coal production. Between climate extremes and record fossil fuel profits, political backlash to climate action by right wing parties is gathering strength.

Flow and stock

When I (Tim) was a graduate student in the 2010s, I was miserable about mass denial of the climate emergency. Global warming remained a fringe cause and an afterthought in national politics. In 2012, climate wasn’t even mentioned in the final presidential debate between Mitt Romney and Barack Obama. How could it? Polls had Climate at the bottom of ranked concerns, with Economy at the top.

This decade is different. We are being battered by extraordinary events at an accelerating clip, and today’s public is increasingly aware that we live in an omnicidal anthropocene. That awareness, however, does not necessarily lead to action. On the contrary, there is a threat that the positive but partial developments in climate mitigation could perpetuate the delusion that present action is sufficient.

While we have begun to shift marginal activities—new car purchases, new efficient buildings—to greener technologies, there remains a risk of discounting the extraordinary threat of the already accumulated carbon in the atmosphere.

This comes down to a distinction between the flow and stock of carbon. The planet does not care about the annual rate of emissions (the flow), what matters is the accumulated stock of carbon in the atmosphere—that’s what governs the degree of warming. The thousands of news articles during the pandemic wondering if a drop in emissions predicted a drop in temperatures exemplified the flow misconception. “Climate is a stock-not-a-flow problem” should be something that people are taught in schools. And it’s not just laypeople. A classic paper by John Sterman tested engineers and scientists at MIT and found that they too were clueless about stocks in their mental models of climate change: “Adults’ mental models of climate change violate conservation of matter.”

The correct mental model is a bathtub. As long as more is flowing from the tap (our emissions) into the tub (atmospheric stock of carbon) than is being drained by the sink (rain forests, oceans, and so on), the water level in the tub will keep rising. The past five years have been the hottest ever on record—as have twenty of the past twenty-two. This consistent warming trend is a direct consequence of the rising water in the bathtub. It will only get worse as the stock of CO2 rises year on year.

Gradualism and gradualists

Ignorance about the stock problem has corresponded to climate mitigation frameworks long-dominated by gradualism. This sanguine orientation assumes that planetary instability is a problem that can be solved over the next few decades through making incremental changes to energy use. Powerful interests prefer deep cuts to carbon be completed far away in the discounted future, when we would, of course, all be richer.

That motivated gradualism fed into policy tools—implemented or merely proposed—like carbon pricing and “energy transition pathways,” and popularized by concepts like the “McKinsey abatement cost curve.” The consultants asked: what are the cheapest emissions to abate? The low-hanging fruit? Gradualism is rooted in heavily-criticized cost-benefit models. Their logic sounds reasonable if we think that the problem is the rate of carbon emissions and cutting the flow of emissions will reduce global warming. This is not the case. The reason has to do with the stock logic of the greenhouse gas effect.

In 2018, the gradualism started to lose its grip. That year, the IPCC Special Report on the impacts of a 1.5ºC change to global temperature—and the “hothouse earth” paper—were published, and a then 15-year-old Greta Thunberg began leading student strikes for climate awareness every Friday.

Here and now

In India, the Yamuna river broke its banks and flooded three water treatment plants; the Delhi state government warned that it would ration drinking water. Drought in Uruguay left more than half its population without safe tap water to drink. The government is providing people with bottled water as the situation is expected to last for months.

Extremes put enormous stress on farms, power grids, ecosystems, and lives. Subway stations, sewers, roads, bridges, transmission cables, and foundations are all designed with a tolerance level. Supercharged with carbon, nature breaks our engineered world. Never forget: the economy is a “wholly owned subsidiary” of nature.

All these disasters spark talk of a “new normal.” That, too, is a form of denial. What we face is planetary instability and disruption of everyday life as burning carbon loads the climate dice so that it throws six after six. Mark Blyth calls it “a giant non-linear outcome generator with wicked convexities. In plain English, there is no mean, there is no average, there is no return to normal. It’s one-way traffic into the unknown.” The earth system is an “angry beast” that we are poking with the carbon stock stick.

Burning oil, gushing cash

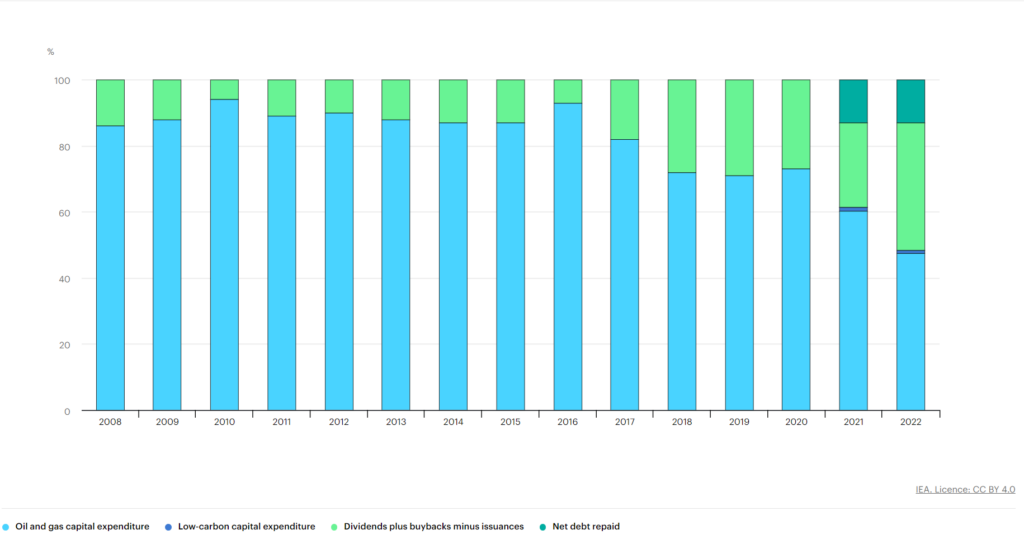

The oil and gas sector has seen record profits over the past two years, both in total and for individual companies. The IEA estimates a staggering $4000 billion in profits were made by the entire industry last year, compared to typical annual estimates of $1500 billion. The five biggest international oil companies alone reported a combined $199bn in net profits in 2022. National oil companies profited the most. Saudi Aramco earned $161bn.

The use of these profits is revealing. In oil booms of the past, high prices consistently attracted financiers and producers to invest heavily in new capacity. Exploration continues despite the fact that no new resources can be exploited if we are to stay within the 1.5C limit. But in contrast to the last oil price boom, international companies have pledged smaller amounts of cash to drilling more polluting fuels, suggesting tacit acknowledgement by finance of the faltering prospects for oil and gas demand.

Are they investing in green? No. Companies are responding defensively to a certain future of falling demand. The supermajors are returning cash to shareholders at a furious pace. Petrostates, however, from Saudi Arabia to the Brazilian municipality of Marica are diverting earnings towards diversifying away from a sunsetting industry.

A billion machines

Today rebuilding the world to be cleaner and more resilient will take vast amounts of physical effort and skilled manual work. Whatever your beliefs about—or definition of—economic growth, deindustrialization is not an option.

Social democrats the world over share a correct diagnosis of the climate crisis. The wealthiest create CO2 through: consumption; controlling production; and corralling democracy. The proposed solutions—expand the welfare state and build a “big green state”—create powerful enemies. That is the planetary impasse we find ourselves in.

If the Inflation Reduction Act showering money on a new cohort of US green industrial interests offers the possibility (not without risks and troubling geopolitical escalations) of green capitalism bridging the impasse, some focus must be brought to bear on another stock. Billions of fossil-burning machines—engines, turbines, furnaces—produce CO2 each day. A “shock of the old” is that we still live in the machine age of Victorians.

The climate crisis requires rapid electrification; new ways and machines to move, heat, cool, melt and make things. All those machines have to be made, financed, marketed, and installed.

We are very early in this process. The IEA estimates that decarbonization will require the amount of power transmission and distribution lines to double and almost triple by 2050. Demand for grain-oriented electrical steel would have to double by 2030.

Cars are one illustration of the stocks and flows problem. There are a billion plus cars on the planet. Sales of internal combustion engine vehicles peaked six years ago, but emissions from road transport won’t peak until 2029. The shift in the flows (sales) towards EVs is already upending political constituencies and threatening international allegiances.

The future is now

Even catastrophes—such as the blazing summer heat still ravaging Europe—don’t directly lead to action. A study found that heat waves in Europe last year killed over 61,000 people. Europe was supposed to be shocked into action after the infamous 2003 heatwave, which killed over 70,000 people, and was the subject of one of the first climate event attribution studies. Without social movements, inaction dominates. Wealthy societies aren’t protected, but they are complacent. The deranged idea—as Amitav Ghosh describes it—that we are safe, that things are under control, that bad things only happen to people who are far away, persists. Anticipating future ruin, we fail to act in the here and now.

Community emergency services can help keep vulnerable elderly and infants cool. Governments can do more to cool people by opening air conditioned public facilities. China has gone further, opening underground bomb shelters to citizens seeking to escape the heat. In Arizona, thirty one days of above 43C/110F heat has led to a surge of deaths and, in a rerun of covid, the government has resorted to extra trailer morgues.

Creative adaptation is urgent. So is cutting the stocks of CO2 in the atmosphere. This is not the logic of costs and benefits, but of means and ends. Not of economics, but survival.

Filed Under