It became apparent early on that ethnicity could be an independent risk factor for Covid-19 and that black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) people were facing worse outcomes than white people.

Tragically, this is particularly true within general practice. As of 22 May, 11 GPs had died from Covid-19. Of those 11, ten were BAME. And a number of groups are recommending moving BAME GPs away from face-to-face consultations.

‘If practices have not yet done a risk assessment, I urge them to do it and protect their BAME staff,’ says British International Doctors Association chair Dr Chandra Kanneganti. ‘If risk is high, BAME GPs should be avoiding face-to-face consultations and working remotely.’

Health leaders acknowledge the risk. Public Health England announced at the start of May it was publishing a rapid review into whether BAME people are more adversely affected by Covid-19, reviewing thousands of health records with an initial focus on frontline workers, specifically doctors and nurses.

As early as 27 April, some secondary care providers took matters into their own hands, with trusts in Lincolnshire and Somerset recognising BAME staff as ‘vulnerable and at risk’. Two days later NHS England chief executive Simon Stevens wrote to GP practices, advising partners to ‘make appropriate arrangements’ to protect their BAME staff on a ‘precautionary basis’. These included ‘working remotely or in a lower-risk area’.

NHS England ran a webinar in early May on its support for BAME doctors. It recommended the risk-reduction framework, led by Professor Kamlesh Khunti of the University of Leicester, which sets out five factors for assessing practice staff: first, age – anyone over 70 is at extra risk; second, sex – around 60% of people admitted to hospital are male; third, underlying health conditions; fourth, ethnicity; and fifth, pregnancy over 28 weeks.

However, for some GPs this was not pragmatic enough, only instructing employers to ‘consider’ factors when making decisions. Rochdale and Bury LMCs chair Dr Mohammed Jiva says: ‘We are very disappointed with the lack of an adequate risk assessment tool for the BAME GP community from NHS England, which has resulted in local clinicians developing a local solution.’

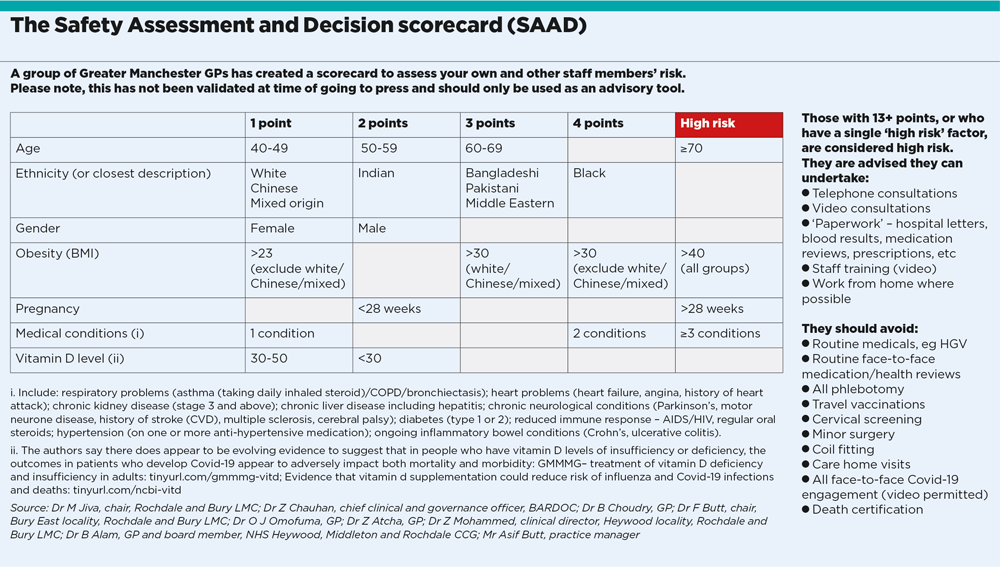

A group of Greater Manchester GPs, led by Dr Jiva, produced a tool to gauge risk, the Safety Assessment and Decision scorecard (SAAD), which commemorates their deceased colleague, Dr Saad Al-Dubbaisi. The scorecard assigns points to the risk factors and adds obesity and vitamin D deficiency to those identified by Professor Khunti’s group.

The SAAD scorecard has been criticised for a lack of occupational health input but Dr Zahid Chauhan, a GP and one of its co-authors, says the group felt the need for a more pragmatic tool to allow GPs to decide their own risk. ‘This is not an occupational health matter – it is a HR matter,’ he says. In other words, GPs and staff – not employers or commissioners – should self-assess and decide whether they should be working on the front line.

Manchester LMCs chair Dr Amir Hannan says the SAAD scorecard is proving popular because ‘it was grounded, produced by frontline BAME GPs and relevant to general practice’.

We are very disappointed at the response at the national level

Dr Mohammed Jiva

One thing the authors of all risk tools seem to agree on is that those at the highest risk should avoid patient-facing roles. Professor Khunti’s guidance says ‘roles which are not directly patient facing are emerging and could be used as redeployment opportunities’, while the SAAD tool list tasks that can be done, and those to avoid.

In smaller practices – or those in areas with a high proportion of BAME GPs – this might be easier said than done. Dr Chauhan says: ‘This will start a discussion on risk management for singlehanded BAME GPs. As things open up, and more patients attend general practice, you could argue there is a higher risk of infection in primary care. GPs can speak to PCNs to put alternative arrangements in place.’

But east London GP and PCN clinical director Dr Farzana Hussain says in an area like hers, this is impossible. ‘Of the 19 GP partners in Newham Central 1 PCN, serving 67,000 residents, all but one are BAME, and 14 are men,’ she says.

‘This idea that networks will save the day is a fallacy. A tool is only useful if you can implement it. Someone has to see patients face to face.’

Dr Hussain adds that it is harder for partners, as they also have duties as employers. ‘How do I say to a practice nurse that I can protect her? If my staff are high risk, what can I do?’

It is also notable that the majority of BAME GPs – especially singlehanders – work in inner cities, where population density is highest. And there was already a recruitment crisis before the pandemic.

Without intervention from the top, GPs in this position face a huge dilemma. Dr Hussain says: ‘I have psychologically resigned myself to more deaths. I can’t find an answer, and I don’t think it is anyone’s fault. We can’t close general practice – we would break the NHS.’

The British Association of Physicians of Indian Origin has held talks with NHS leaders on the issue. Its president Dr Ramesh Mehta tells Pulse adequate PPE would help. He says: ‘Appropriate PPE is still not available. GPs were informed that certain costs can be claimed back but the official line is that equipment that isn’t part of standard [Public Health England] PPE doesn’t get refunded. So the GPs who’ve purchased gowns or better masks for staff won’t see a refund. This only encourages primary care facilities to stick with PHE guidance, which we know is inadequate.’

Dr Jiva agrees GPs of all ethnicities scoring high ‘need to raise the issue of enhanced PPE with their CCG in line with WHO recommendations’.

He also points out what he sees as a further risk factor: ‘There is emerging data around vitamin D and Covid-19, and all ethnicities may benefit from taking this supplement.’ However, there is as yet no official advice on the subject.

For Dr Hussain, there are few silver linings for singlehanded BAME GPs but she says GPs’ ability to innovate is one. ‘We are getting digitally savvy, and can do most consultations remotely. And I’ve never seen so much learning and sharing. For example, our [drive-in] childhood vaccinations scheme meant nurses only had two minutes’ contact, reducing risk.’

It may be that such innovation turns out to be the best protection for the most vulnerable GPs.