What is the myth and where did it come from?

The adult dose is scaled down according to the size of the child. A dose of paracetamol (for example) is calculated on roughly 10-15mg/kg per dose.1 Unsurprisingly, this formula gives you an adult dose if you calculate the amount based on a healthy adult weight. There are notable exceptions to this rule, such as the recommended dose of prednisolone for exacerbations of asthma in children. The ceiling of the dose is hit at an early age with a dose of 2mg/kg of prednisolone.

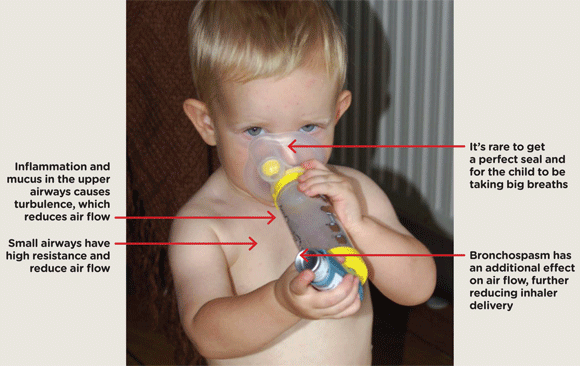

So it is not uncommon to see small children be given β-agonist inhalers with a recommended dose of one puff. The logic is sound but there are forces at work here that make this plan flawed. These are science, chaos and perhaps the most powerful force of all: the child.

What is the reality?

The reality is that small children usually need a larger number of puffs of their reliever β-agonist inhaler than an adult would need. This is because there are several factors that conspire to restrict the delivery of the drug.

The first of these factors is science. Flow through a tube is dependent on the length and the width of the tube. In an oversimplified way, we most often use the Hagen-Poiseuille equation to calculate what flow should be through the airways of the human body. The smaller the tube’s diameter, the greater the resistance and therefore the less air flowing. If we use that equation, we find that flow will be roughly halved in a healthy four-year-old compared with an adult. Once you add in a bit of bronchospasm, the effect of narrow tubes becomes considerable. A mere 10% reduction in size results in a 50% reduction in flow.

The second factor that favours larger doses is chaos. While science would like to imagine that the particles of β-agonist are charging their way to the bronchi in a perfect laminar flow, the truth is far from this. There is turbulence caused by the accompanying upper respiratory tract infection, mucus in the airway and anything else that makes this child’s bronchial tree something other than a perfect tube. When it comes to air flow, turbulence is unquantifiable chaos and has been called ‘the most important unsolved problem of classical physics’.2 The end result is always reduced air flow. How much is that reduction? It is an unquantifiable reduction but I am told that turbulence roughly halves the flow of air through a tube.

These two factors already greatly reduce the effectiveness of inhaled therapy in a child. There is one more factor to consider, and that is the child’s willingness. The efficacy of any inhaled therapy depends on the patient forming a good seal with the device, using it correctly and taking a good inspiration. This is the ideal situation but it hardly ever happens in the preschool patient group, at least not to begin with. In time young children often learn to use an inhaler and spacer very well, but the chances of getting good concordance to begin with are slim to none.

Why it’s important to be generous with reliever inhaler doses in preschool children

How does this change my practice?

When a child needs β-agonist bronchodilators for a viral wheeze (not bronchiolitis) it is best to be generous with the dose. The relevant NICE clinical knowledge summary recommends up to 10 puffs of salbutamol.3

Knowing how many barriers there are between inhaler and receptor should also drive us to maximise the effectiveness of delivery.

There are lots of things that can help improve the concordance with an inhaler and spacer in young children:

- Make it into a game. Maybe the teddy bear wants a couple of puffs before the child? Perhaps using the inhaler and spacer can be related to being a steam train, or a space man?

- Make it a familiar item to the child. If they only see the spacer when they have it forced on them, it will have a negative association. Let them play with it on their own.

- Be realistic. To begin with it is likely to be an ordeal to get a two-year-old to accept a spacer. They will most likely need to be restrained and it helps to have two people.

- Be positive. Initial reluctance from the child is soon followed by acceptance. Sometimes the child will end up asking for their inhaler.

- Be clear. A good seal between the mask and the child’s mouth and nose is essential for the device to work. If the valve isn’t seen to be moving, the system isn’t working.

So be generous with the reliever inhaler in the small child with acute wheeze. Because children are not small adults and you can’t shrink the dose to fit the child.

References

- MHRA. Liquid paracetamol for children: revised UK dosing instructions. 2011

- Eames I, Flor J. New developments in understanding interfacial processes in turbulent flows. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 2011

- Scenario: Viral-induced wheeze/possible asthma, NICE CKS. 2017

Dr Edward Snelson is a consultant paediatrician specialising in paediatric emergency medicine at the Sheffield Children’s Hospital. He is the author of The Essential Clinical Handbook of Common Paediatric Cases and of gppaedstips.blogspot.co.uk – a site for GPs to keep up to date with paediatrics in primary care.

Before becoming a paediatrician, he was a GP for over five years, and now uses that experience to fuel his educational work in primary care.

Twitter: @sailordoctor