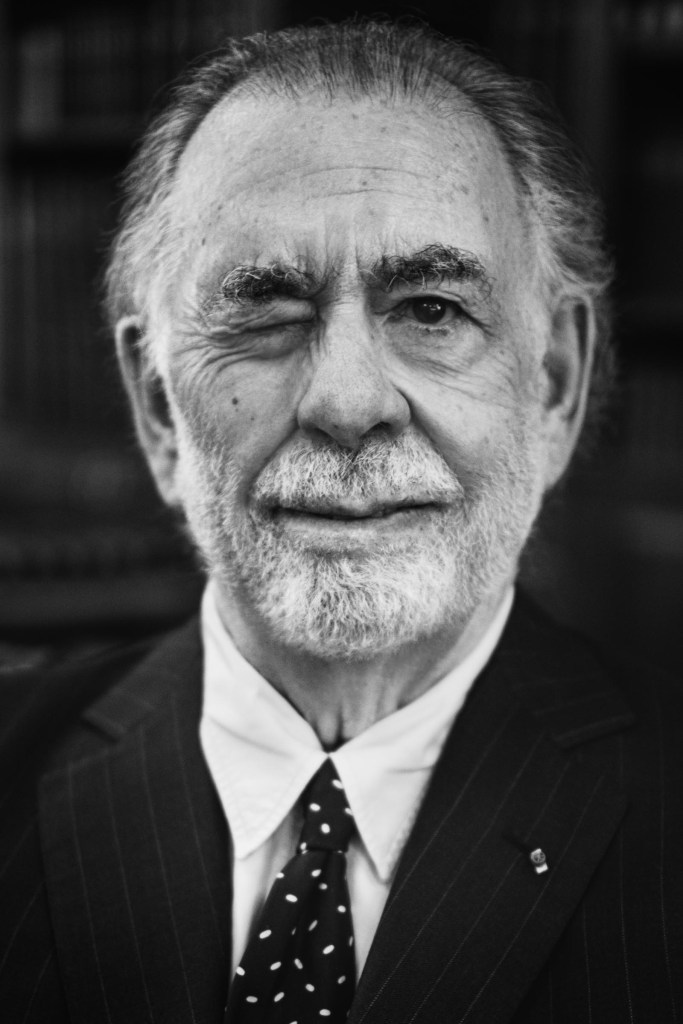

F rancis Ford Coppola is sitting in a large, library-like space that is right next to the gift-shop area of his Inglenook Winery in Napa, California, behind a usually closed set of doors. The awards, family pictures, and massive collection of vintage zoetropes are all in the lobby. The tasting room, which resembles something like a 15th-century monastery, albeit one with a state-of-the-art espresso machine, is on the other side of the chateau. The room where the 85-year-old filmmaker, winemaker, and overall rainmaker is currently mugging for a photographer and fiddling with his breakaway glasses is filled with floor-to-ceiling shelves of leather-bound books, paintings, a grand piano, a long conference table, and expensive-looking, comfortable chairs. It looks like a cross between a museum wing and the world’s most artfully decorated man cave.

It’s hard to tell whether Coppola is kidding when he asks if this room has always been here; his photographic memory is a point of pride. Anyone who spends a day in the company of the director of the Godfather films, Apocalypse Now, and other great American movies of the past 50-plus years will inevitably hear anecdotes from his shoots, near-verbatim recitations of decades-old conversations, stats about the wine industry, and any number of random facts off the top of his head. But if there is one thing you sense about Coppola, it’s that everything seems to be in a state of flux. He has just returned from a two-week trip to China. He’s considering spending time in London, since Napa reminds him of his wife, Eleanor, to whom he’d been married for 60 years until her death in April. He’s not sure where he’s going to be next week.

Or, given how restless and enthusiastic the man who lent his name to this 235-acre winery — part of a multimillion-dollar empire that also includes resorts and a cannabis-lifestyle brand — seems about everything he’s involved with, maybe he simply sees the room for the first time every time. That’s how you manage to keep reinventing things, like the wine industry or your old movies (he’s spent the past dozen years returning to his old works and revising, recutting, remixing them) or whatever project you’ve thrown yourself into.

After lunch, the filmmaker casually mentions that he’s figured out how to revolutionize how wine is produced, which involved purchasing 120 different fermenting tanks, one for each lot. Do we want to go see them? Coppola quickly piles me, along with a photographer and a publicist, into a compact electric car before jumping behind the wheel and speeding us off roughly 500 yards away to a “wine cave” he had constructed to house these new acquisitions.

When we get to the cave’s opening, there’s a semitruck parked in the middle of the entrance and pallets of boxes, all filled with wine bottles, that seem to be blocking the way. None of this deters Coppola, who simply maneuvers around the pallets and slides past the truck by mere millimeters, as workers and managers scurry out of the car’s way. Hopping out of the vehicle, he proudly shows off rows upon rows upon rows of giant, gleaming silver cylinders. Then Coppola ushers everyone back into the car, which he somehow manages to quickly reverse out of this impossibly tight space with all the deftness of a professional stunt driver. (This is apparently not the first time he’s done this tour with members of the media.) It feels almost like this self-described “boy scientist” who grew up wanting to change the world has crossed himself with the regal Vito Corleone and the compellingly unhinged Colonel Kurtz.

“I wanted you to see those, so that you could properly see this,” he says once we get out of the car, sweeping his arm across the view of the vineyard. “Because this is what’s at stake if this movie doesn’t succeed. This is why Megalopolis really has to succeed.”

Yes, Megalopolis. Coppola’s first new movie in 13 years is a white whale he’s actually been chasing for close to 40 years, a story he describes as “a Roman Empire epic set in modern America” that somehow seems remarkably in tune with our chaotic, end-of-days era. Focusing on an architect-slash-futurist dreamer named Cesar Catilina (Adam Driver) who wants to turn the shining city on a hill in the center of New Rome into a bona fide utopia — and has invented a new material called megalon that will help him accomplish this goal — it’s a sprawling, ambitious, all-over-the-map story about a dying republic filled with corrupt politicians, club-hopping hedonists, a Caligula-like figure who bears a strong resemblance to a recent former president (played by no less than Jon Voight), and a bottle-blond Aubrey Plaza as a character named Wow Platinum.

At Cannes, where it premiered in May, Megalopolis managed to be the single most divisive film of the festival; love it or hate it, Coppola’s huge swing for the philosophical fences is a truly singular work — and is exactly the movie that he wanted to make. (It’s set to hit theaters on Sept. 27.) That Coppola somehow managed in his eighties to will this long-gestating pet project into being and self-finance it against his winery for $120 million is borderline unbelievable, even given his legacy as someone willing to bet a fortune and/or a film studio to follow a dream. “I have everything to lose here,” he says, referring to this portrait of the decline, fall, and Phoenix-like rise of a civilization. “And, in a way, I have nothing left to lose anymore.”

You’ve been talking about Megalopolis since the late 1970s. At what point did you seriously start to think of this as a real project?

Well, basically … every one of my movies had a different style. I always pretty much had one word that I could tell myself about a film — like, The Conversation was about privacy. The Godfather was about succession. Apocalypse Now was about morality. And I thought that what the movie was about ought to determine what style it’d be in. But I started to think, “When I’m an older, elderly person, what will my style be?” So I started keeping scrapbooks of things that I was interested in — stuff I was reading in the newspaper, [quotes from] books, political cartoons. I thought they would show me what my true style was.

Now, I wasn’t trying to write Megalopolis over 40 years. It’s more that these scrapbooks were going on for 40 years. I started to come around to the idea that I wanted to make a Roman epic, because Roman epics were always fun. They had gladiators and conspiring crazy people like Caligula or Nero. And then one of the things I read proposed that America was the modern-day Rome, so that you could take those stories and set them in modern America, and it would work. I started to fashion a rough approximation of what the Megalopolis story might be, but I didn’t know how to write it. I believe that we all get a gift. I got lucky. I got three.

What are they?

A good imagination, fantastic memory, and Cassandra-like ability to see the future. Those are my three talents. I don’t have that thing some filmmakers have, which is to see a whole movie in your head and be able to just write it down. I think Steven [Spielberg] has that gift. I don’t. I only can write a script as if I’m going to rewrite it 100 times.

Those aren’t bad gifts for a filmmaker to have, though.

The last one helped with Megalopolis. The same thing happened with The Conversation, because the movie was about a private eavesdropper and I wrote it in the 1960s, but people didn’t even know there was such a thing until Watergate happened 10 years later. With Megalopolis and the concept of America as Rome, a lot of people said, “Well, why would anyone want to go see a movie about that?” But it’s happening right now in our lives.

What I didn’t want to happen is that we’re deemed some woke Hollywoood production.

You did a few readings of an earlier Megalopolis draft in 2001, with Robert De Niro, Leonardo DiCaprio, Edie Falco, Uma Thurman, and a few others, right? How similar was that version of Megalopolis to what you made?

It was the pregnant version of it, but it wasn’t all that similar. There were different periods where I took stabs at it. What’s the name of the actor in The Sopranos, the main one?

James Gandolfini?

Yes! He gave me a lot of great suggestions, actually. He read the part of the mayor back when I did a reading of a draft in 2001.

And you were about to start production when—

9/11 happened. Here I’m making a movie about utopia and the world in which we achieve this breakthrough that I am so hopeful about, and then a huge terrorist attack happens. I couldn’t write my way out of it. So I abandoned the project.

Around 2017 or so, Anthony Bourdain invited me to come on to his travel show. He came to Sicily, and it was a lot of fun, but when I eventually saw the episode, I thought, “I look like a whale.” This is not healthy for me. I signed myself up for this five-month program at Duke Fitness Center, where [The Godfather writer] Mario Puzo had gone a few times, and lost close to 50 pounds. You don’t see any 85-year-old, 300-pound men running around.

But on the days where it would be these strict exercise regimens, I started listening to some of the readings of Megalopolis just for the hell of it, and thought, “This feels more relevant than ever.” I realized that even though the script was 20 years old, I could still do it.

There were reports of chaos on the set.

There were some disagreements that had to do with the studio I was shooting at in Atlanta. “You have an art department with five art directors. I want to cut one of them.” “Well, if you cut one, we’ll all resign.” I did, and they did. It’s similar to what has happened at different times in my career, where basically it was over what the money was being spent on. But I did wrap on schedule, which I had to do because if I had been going over schedule, I would’ve been doomed.

You’ve talked about a famous dinner you arranged right before you started shooting The Godfather, where you put Marlon Brando at the head of the table with the rest of the cast, and the dynamic of the Corleone family pretty much fell into place. Did something similar happen with this cast?

I did a weird thing with Megalopolis because I could only rehearse with about a third of the cast, maybe a little more. I had Aubrey Plaza. I had Nathalie Emmanuel. I didn’t have Adam. But I had given everybody understudies like it was a play, and I said, “What I’ll do is, I’ll do the rehearsal, and regarding the actors I don’t have, I’ll use the understudies.” It was a very creative, interesting week of rehearsals. You could see the actors find the characters. Shia [LaBeouf] really took to it. I had no experience working with him prior to this, but he deliberately sets up a tension between himself and the director to an extreme degree. He reminds me of Dennis Hopper, who would do something similar, and then you’d say, “Just go do anything,” and then they go off and do something brilliant.

You cast Jon Voight in a role that bears a strong resemblance to Donald Trump, and I’m going to guess that there are some political viewpoints he holds that you don’t share.

What I didn’t want to happen is that we’re deemed some woke Hollywood production that’s simply lecturing viewers. The cast features people who were canceled at one point or another. There were people who are archconservatives and others who are extremely politically progressive. But we were all working on one film together. That was interesting, I thought.

Would you say the Megalopolis shoot was closer to The Godfather or Apocalypse Now?

Apocalypse Now. No helicopters this time. That’s the big difference [laughs].

Have you ever felt like the success of The Godfather became like an albatross around your neck?

No. Never. The Godfather opened up the world to me and gave me the ability to talk to virtually anyone in the world. Which has been a gift, because I’ve met some incredibly wonderful people as a result. Some of the greatest people in the world have wanted to talk to me simply because I was the guy who made that film. Some of the very worst people in the world, too, but that’s another story. The composer Richard Strauss has this quote: “I may not be a first-rate composer, but I am a first-class second-rate composer.” All I ever wanted out of the film industry was just to be part of the group.

I believe that we all get a gift. I got lucky. I got three.

You were part of a group, though. As someone who was a key member of what we now call “New Hollywood,” why do you think that moment has been so romanticized?

Part of it is because of the films themselves — look at George [Lucas’] and Marty [Scorsese]’s early movies. They’re really great. We’d come from film school and working with Roger Corman, a lot of us, and suddenly we were able to make it past the studio gates. It became this maverick thing, and people love mavericks. You know, the whole thing about how the things you get in trouble for in your twenties is what you get praised and win awards for in your sixties! I think we were lucky to find each other, but I really believe it comes down to the movies. Not that book.

By “that book,” do you mean Peter Biskind’s Easy Riders, Raging Bulls [about Coppola, Scorsese, and the New Hollywood filmmakers of the 1970s]?

Yeah. Totally full of inaccuracies. I just lost my wife of 60 years, Eleanor, and one of the reasons I’m in Napa right now is because it’s forced a kind of probate — I have estate issues, and I have no idea how it’s going to work out. Of course, Megalopolis is going to open and I’m very optimistic about what’s going to happen. I think people are going to go see it because, if for no other reason, they want to see it for themselves, which I think is good. But if there’s some wealth left here, I want it to go to being some sort of subsidy for young filmmakers in our family foundation.

Had Eleanor been sick for a while, or was this out of the blue?

She had a noncancerous tumor called a thymoma. Fourteen years ago, when it was discovered, the doctor said, “It’s a little big to take out right now. If she does three months of chemo, then it should make it smaller and I can take it out.” And Eleanor said, “I’m not doing chemo.” She wanted to do what she wanted to do; she made several movies, and ultimately, it just got so big and so painful that she did not want to live anymore.

How have you been dealing with the grief?

The most comfort I have is … there’s something that Marcus Aurelius said that’s basically “When you lose a loved one, you should honor them by trying to be more like them. It’s in your actions that they will remain alive.” So I try to do things that she would do. I have some friends who are elderly now, and it’s not my nature to call them up and say, “How are you doing?” That would be her nature, though. So I do things to try to be more like that, to keep her in me.

Let’s go back to The Godfather for a second. Why do you think the movie endured the way it has?

It was the right movie for the right time, with the right cast, with the right artists. Somehow, everything just lined up. I have a theory of one of the reasons why it was so successful, which is [something] no other gangster film ever did, is it had the children of gangsters in it. Which is funny, because it’s a small thing. But one of the things that made The Godfather really different is that you not only see these men doing what they do, you also see their family and what so much of Italian American life was at that time.

What do you think about works like The Sopranos, which take the mythology of the Godfather films and either build on it or deconstruct it?

The Sopranos is incredible. [David Chase] wanted to be a moviemaker, and you can see all of these cinematic influences in the show. And then he raised television storytelling to the level of movies, and maybe surpassed them. It’s kind of amazing.

How were you able to handle the success of the first Godfather?

My life before and after that film — it was night and day. I was broke. I would end up eating Kraft macaroni-and-cheese dinners, which is why I got so fat. Then I went from a struggling filmmaker with a few movies under his belt to the guy who made The Godfather. Changed my life. It’s like a million-to-one shot how that happened. It caused some problems, too.

Such as?

Well, I had a wonderful older brother who was very good to me, five years older, and he used to write his work under the name August Floyd Coppola. He’s Nicolas Cage’s father. I just wanted to be his kid brother. He was such a wonderful older brother. He’s the one who took me to see all those movies. So when The Godfather came out and suddenly Francis Ford Coppola was somebody, he couldn’t be August Floyd Coppola anymore because it seemed as though he was copying me — but I was copying him, and that caused the heartbreaking issue that went on and on throughout my life.

Your success changed the dynamic between you two?

I still worshiped him. He died not talking to me. [Long pause.] Do you know the story about the first preview for The Godfather: Part II?

What happened?

So the movie goes between young Vito Corleone coming to America and Michael Corleone in the 1950s. It would be 10 minutes in one story, then we’d switch to 10 minutes of the other story. We had finished the mix on the movie and were all set to open. We previewed it in San Francisco — and it was a disaster. The audience hated it. I didn’t go to bed. I went under the bed and I hid. And in that state, under the bed, I realized that 10 minutes wasn’t long enough. It should be double that — I should cut back and forth every 20 minutes, because the audience wasn’t ready to be yanked out of one story and yanked in the other story.

So I went to the editors and I said, “Guys, we have to make 120 picture cuts to do what I have in mind,” which was to basically double the scenes for 10 minutes to 20 minutes. They stayed up all night for two nights and made the changes. We took it back to San Diego — and it was a different story entirely. The audience loved it. They were wildly impressed. Originally, they hated the acting. Now, it was the best acting they had ever seen, they said. It was the same acting [laughs]!

How has your relationship with directing actors changed over the years?

People don’t understand that after I made The Rainmaker [1997], I sort of quit for 14 years. I literally said, “I’m going to stop being a professional director, and I’m going to just be a student for a while. I’m going to try to understand what making movies is.” And I did that by self-financing some very small, low-budget movies. The one I made in Romania, Youth Without Youth [2007] — I made that for under a million dollars. Then I went to Argentina and I made Tetro [2009], same thing. People said, “You fell off the map. Those films were not successful.” They weren’t meant to be successful. They were meant to teach me what making movies really was. And I learned a lot during that period about acting. I did unusual rehearsals.

There were reports from the Megalopolis set that you kissed and touched extras in a way some people found inappropriate. Was that a rehearsal thing that got out of hand?

You’re talking about the Guardian piece, which is totally untrue. If you read that piece, you’ll realize that whoever the sources were — and I honestly don’t know who the sources were — it’s the same people who provided quotes for that Hollywood Reporter piece that said all these people were fired or resigned, and that there was a mass exodus, all of that. And the truth of the matter is, they were looking for some sort of dirt. The young women I kissed on the cheek, in regards to the New Year’s scene, they were young women I knew.

It’s all so ridiculous. Look at the timing of that article. It’s right before we’re about to premiere the film at Cannes. They’re just trying to damage the picture.

I want to start a conversation. You can’t have a utopia without a conversation.

Why do you think they’re trying to damage the picture?

There’s a prevailing tendency in Hollywood to say, if you follow our rules, you’ll have a better chance of a success. “Well, what about Francis? He doesn’t follow your rules.” “Well, look, what’s going to happen to him, he’s going to have a failure.” I’m trying to do something different here. Film is change. I mean, the movies that your grandchildren are going to make are going to be nothing like what we see now.

How do we keep this art form going if so many big benefactors are worried about nothing but, in your words, paying debts?

The filmmakers themselves have to say what films they’ll make and won’t make. What really closed the door was Heaven’s Gate [the 1980 film that eventually bankrupted United Artists]. Everyone got scared after that. I’ll tell you a very funny story, because I invited Michael Cimino for Thanksgiving and he came with Isabelle Huppert. It was at [production designer] Dean Tavoularis’ house; we were having Thanksgiving dinner, and his mother asked Cimino, “How’s your turkey?” And he said, “Well, we’re getting really bad reviews.…” [Laughs.]

Now that you’ve finally made Megalopolis, is that it for you?

No, I’m working on two potential projects right now. One is a regular sort of movie that I’d like someone to finance and make in England, because I don’t have a big history with my wife in England. Everywhere else I go, I’m reminded of her all the time. The other is called Distant Vision, which is the story of three generations of an Italian American family like mine, but fictionalized, during which the phenomenon of television was invented. I would finance it with whatever Megalopolis does. I’ll want to do another roll of the dice with that one.

Megalopolis is a film about the death and rebirth of a republic. And I think it’s safe to say that I feel like our republic is as close to being within its death throes—

As it’s ever been. Yes. Maybe the War of 1812. That was dicey, too. They burned the White House.

But the movie ends on an optimistic note.

It’s hopeful.

How do we bring that sense of hope into our everyday lives?

This steers me toward politics, and my publicist will yell at me if I start talking about politics [laughs]. This movie won’t cure our ills. But I honestly believe that what will save us is the fact that we’ve got to talk about the future. We want to be able to ask any questions we have to ask in order to really look at why this country is divided right now, and that’s going to provide an energy that will defeat those people who want to destroy our republic. I made this film to contribute to that. And all I want is for this movie to start a conversation. You can’t have a utopia without a conversation.