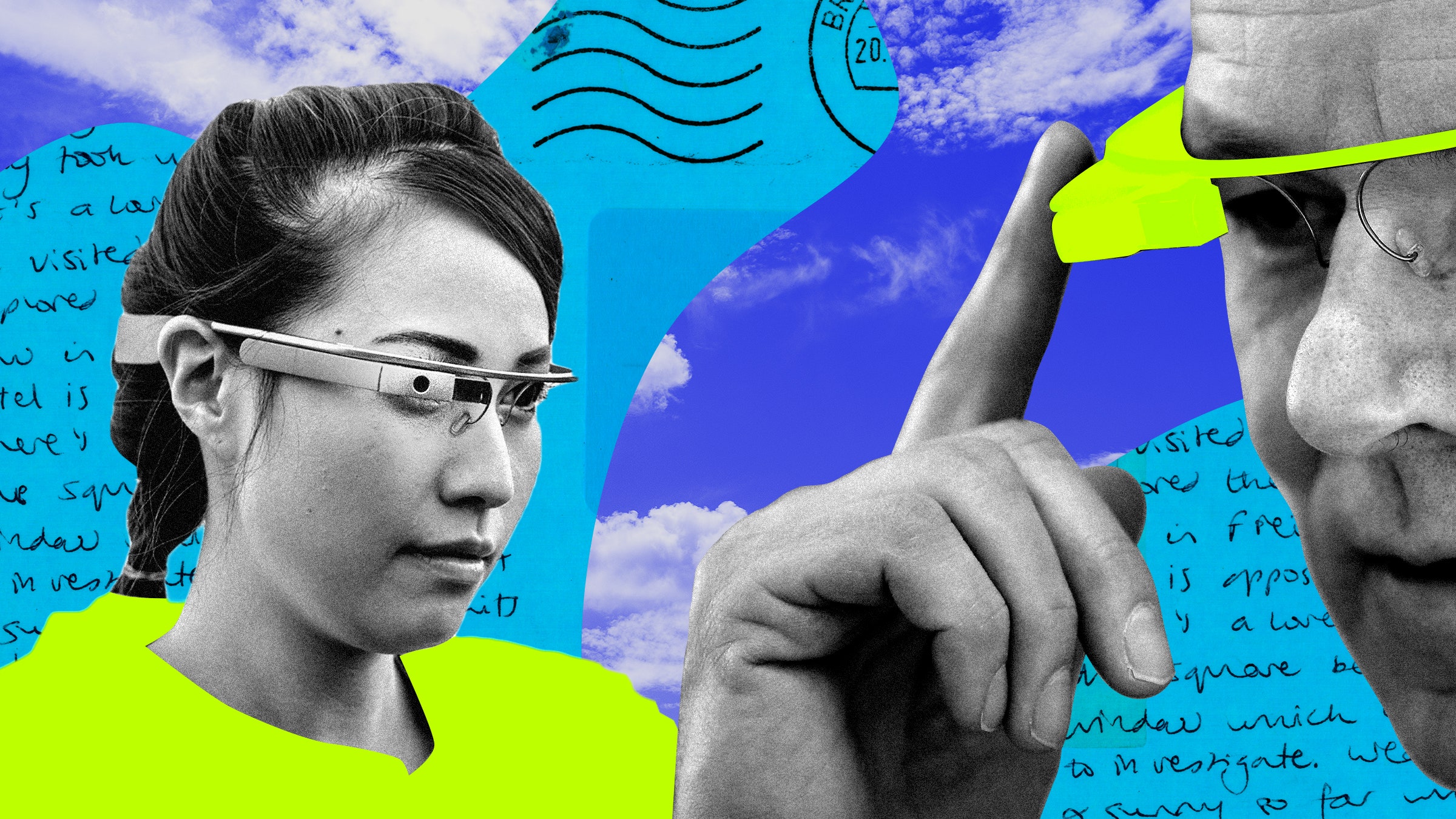

For her 38th birthday, Chela Robles and her family made a trek to One House, her favorite bakery in Benicia, California, for a brisket sandwich and brownies. On the car ride home, she tapped a small touchscreen on her temple and asked for a description of the world outside. “A cloudy sky,” the response came back through her Google Glass.

Robles lost the ability to see in her left eye when she was 28, and in her right eye a year later. Blindness, she says, denies you small details that help people connect with one another, like facial cues and expressions. Her dad, for example, tells a lot of dry jokes, so she can’t always be sure when he’s being serious. “If a picture can tell 1,000 words, just imagine how many words an expression can tell,” she says.

Robles has tried services that connect her to sighted people for help in the past. But in April, she signed up for a trial with Ask Envision, an AI assistant that uses OpenAI’s GPT-4, a multimodal model that can take in images and text and output conversational responses. The system is one of several assistance products for visually impaired people to begin integrating language models, promising to give users far more visual details about the world around them—and much more independence.

Envision launched as a smartphone app for reading text in photos in 2018, and on Google Glass in early 2021. Earlier this year, the company began testing an open source conversational model that could answer basic questions. Then Envision incorporated OpenAI’s GPT-4 for image-to-text descriptions.

Be My Eyes, a 12-year-old app that helps users identify objects around them, adopted GPT-4 in March. Microsoft—which is a major investor in OpenAI—has begun integration testing of GPT-4 for its SeeingAI service, which offers similar functions, according to Microsoft responsible AI lead Sarah Bird.

In its earlier iteration, Envision read out text in an image from start to finish. Now it can summarize text in a photo and answer follow-up questions. That means Ask Envision can now read a menu and answer questions about things like prices, dietary restrictions, and dessert options.

Another Ask Envision early tester, Richard Beardsley, says he typically uses the service to do things like find contact information on a bill or read ingredients lists on boxes of food. Having a hands-free option through Google Glass means he can use it while holding his guide dog’s leash and a cane. “Before, you couldn’t jump to a specific part of the text,” he says. “Having this really makes life a lot easier because you can jump to exactly what you’re looking for.”

Integrating AI into seeing-eye products could have a profound impact on users, says Sina Bahram, a blind computer scientist and head of a consultancy that advises museums, theme parks, and tech companies like Google and Microsoft on accessibility and inclusion.

Bahram has been using Be My Eyes with GPT-4 and says the large language model makes an “orders of magnitude” difference over previous generations of tech because of its capabilities, and because products can be used effortlessly and don’t require technical skills. Two weeks ago, he says, he was walking down the street in New York City when his business partner stopped to take a closer look at something. Bahram used Be My Eyes with GPT-4 to learn that it was a collection of stickers, some cartoonish, plus some text, some graffiti. This level of information is “something that didn’t exist a year ago outside the lab,” he says. “It just wasn’t possible.”

Danna Gurari, assistant professor of computer science at the University of Colorado at Boulder, says it’s exciting that blind people are on the bleeding edge of technology adoption rather than an afterthought, but it’s also a bit scary that such a vulnerable population is having to deal with the messiness and incompleteness of GPT-4.

Each year, Gurari organizes a workshop called Viz Wiz at the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition conference to bring companies like Envision together with AI researchers and blind technology users. When Viz Wiz launched in 2018, only four teams participated in the workshop. This year, more than 50 teams signed up.

In early testing of some image-to-text models, Gurari has found that they can make up information, or “hallucinate.” “Most of what you can trust is only the high-level objects, like ‘I see a car, I see a person, I see a tree,’” she says. That’s not trivial information, but a user can’t necessarily trust that the AI will correctly tell them what’s in their sandwich.

“When blind people get this information, we know from prior interviews that they prefer something rather than nothing, so that’s fantastic. The problem is when they’re making decisions off of bogus information, that can leave a bad taste in their mouth,” she says.

If an AI gets a description wrong by misidentifying medication, for example, it could have life-threatening consequences.

The use of promising but flawed large language models to help blind people “see” the world can also leave them exposed to AI’s tendency to misidentify people’s age, race, and gender. The data sets that have been used to train AI are known to be skewed and biased, encoding prejudices and errors. Computer vision systems for object detection have a history of Western bias, and face recognition has had less-accurate outputs for groups like Asian people, transgender people, and women with dark skin.

Bahram acknowledges that these are risks and suggests that systems provide users with a confidence score so they can make more informed decisions about what the AI thinks it’s seeing. But he says blind people have a right to the same information as sighted people. “It’s a disservice to pretend that every single sighted person doesn’t immediately notice [attributes like gender or skin tone], whether they act upon it or not,” he says. “So why is [withholding] that fair to somebody who doesn’t have access to visual information?”

Technology can’t confer the basic mobility skills a blind person needs for independence, but Ask Envision’s beta testers are impressed with the system so far. It has limitations, of course. Robles, who plays the trumpet, would like to be able to read music, and for the system to provide more spatial context—where a person or object is in a room, and how they’re oriented—as well as more detail.

“It’d be really cool to know, ‘hey, what’s this person wearing?’” she says. “It could get it wrong. AI isn’t perfect by any means, but I think every little bit helps as far as description goes.”