In the past decade, autonomous driving has gone from “maybe possible” to “definitely possible” to “inevitable” to “how did anyone ever think this wasn’t inevitable?” to "now commercially available." In December 2018, Waymo, the company that emerged from Google’s self-driving-car project, officially started its commercial self-driving-car service in the suburbs of Phoenix. At first, the program was underwhelming: available only to a few hundred vetted riders, and human safety operators remained behind the wheel. But in the past four years, Waymo has slowly opened the program to members of the public and has begun to run robotaxis without drivers inside. The company has since brought its act to San Francisco. People are now paying for robot rides.

And it's just a start. Waymo says it will expand the service's capability and availability over time. Meanwhile, its onetime monopoly has evaporated. Every significant automaker is pursuing the tech, eager to rebrand and rebuild itself as a “mobility provider. Amazon bought a self-driving-vehicle developer, Zoox. Autonomous trucking companies are raking in investor money. Tech giants like Apple, IBM, and Intel are looking to carve off their slice of the pie. Countless hungry startups have materialized to fill niches in a burgeoning ecosystem, focusing on laser sensors, compressing mapping data, setting up service centers, and more.

This 21st-century gold rush is motivated by the intertwined forces of opportunity and survival instinct. By one account, driverless tech will add $7 trillion to the global economy and save hundreds of thousands of lives in the next few decades. Simultaneously, it could devastate the auto industry and its associated gas stations, drive-thrus, taxi drivers, and truckers. Some people will prosper. Most will benefit. Some will be left behind.

It’s worth remembering that when automobiles first started rumbling down manure-clogged streets, people called them horseless carriages. The moniker made sense: Here were vehicles that did what carriages did, minus the hooves. By the time “car” caught on as a term, the invention had become something entirely new. Over a century, it reshaped how humanity moves and thus how (and where and with whom) humanity lives. This cycle has restarted, and the term “driverless car” may soon seem as anachronistic as “horseless carriage.” We don’t know how cars that don’t need human chauffeurs will mold society, but we can be sure a similar gear shift is on the way.

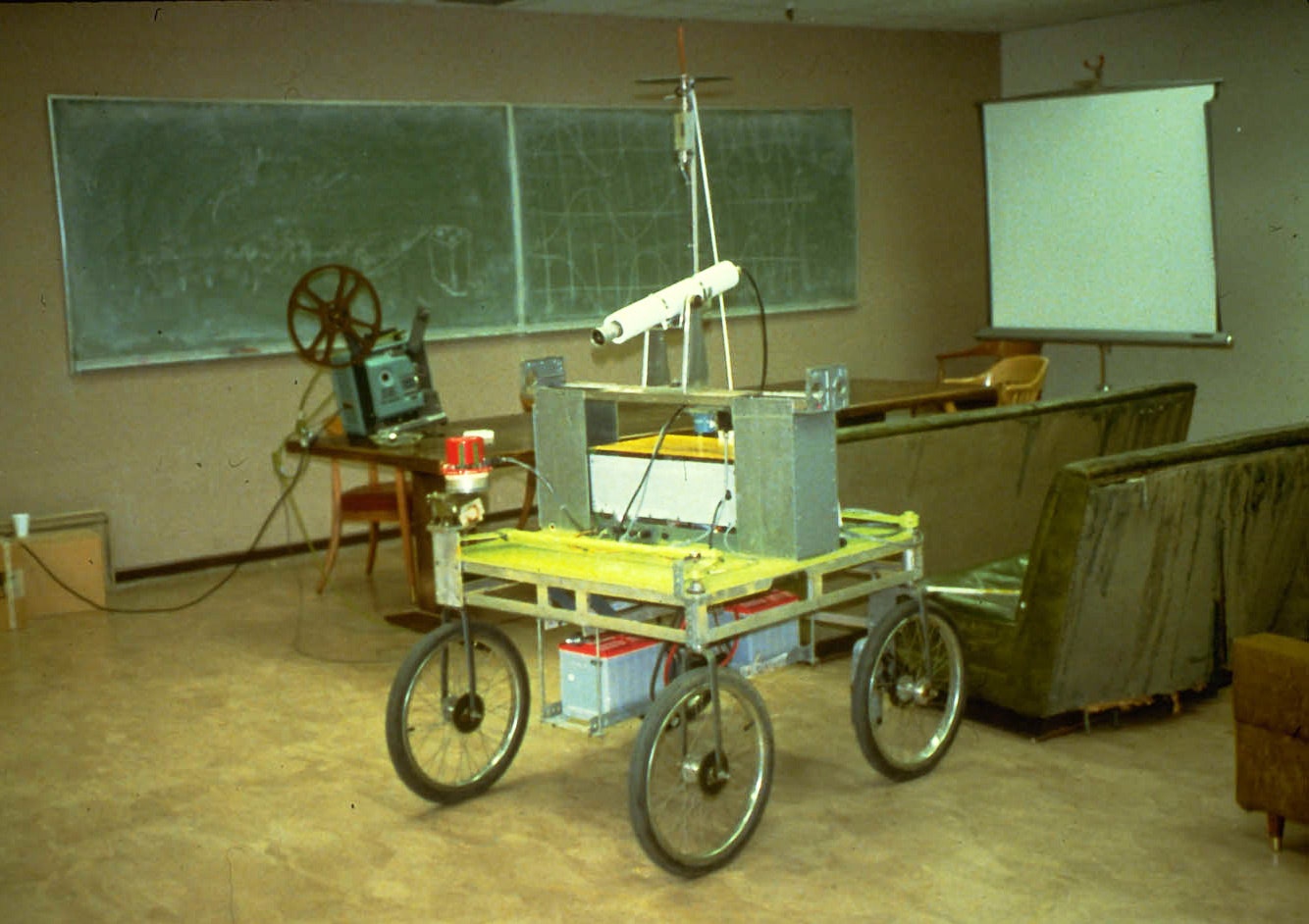

Just over a decade ago, the idea of being chauffeured around by a string of zeros and ones was ludicrous to pretty much everybody who wasn’t at an abandoned Air Force base outside Los Angeles, watching a dozen driverless cars glide through real traffic. That event was the Urban Challenge, the third and final competition for autonomous vehicles put on by Darpa, the Pentagon’s skunkworks arm.

At the time, America’s military-industrial complex had already thrown vast sums and years of research trying to make unmanned trucks. It had laid a foundation for this technology, but stalled when it came to making a vehicle that could drive at practical speeds, through all the hazards of the real world. So, Darpa figured, maybe someone else—someone outside the DOD’s standard roster of contractors, someone not tied to a list of detailed requirements but striving for a slightly crazy goal—could put it all together. It invited the whole world to build a vehicle that could drive across California’s Mojave Desert, and whoever’s robot did it the fastest would get a million-dollar prize.

The 2004 Grand Challenge was something of a mess. Each team grabbed some combination of the sensors and computers available at the time, wrote their own code, and welded their own hardware, looking for the right recipe that would take their vehicle across 142 miles of sand and dirt of the Mojave. The most successful vehicle went just seven miles. Most crashed, flipped, or rolled over within sight of the starting gate. But the race created a community of people—geeks, dreamers, and lots of students not yet jaded by commercial enterprise—who believed the robot drivers people had been craving for nearly forever were possible, and who were suddenly driven to make them real.

They came back for a follow-up race in 2005 and proved that making a car drive itself was indeed possible: Five vehicles finished the course. By the 2007 Urban Challenge, the vehicles were not just avoiding obstacles and sticking to trails but following traffic laws, merging, parking, even making safe, legal U-turns.

When Google launched its self-driving car project in 2009, it started by hiring a team of Darpa Challenge veterans. Within 18 months, they had built a system that could handle some of California’s toughest roads (including the famously winding block of San Francisco’s Lombard Street) with minimal human involvement. A few years later, Elon Musk announced Tesla would build a self-driving system into its cars. And the proliferation of ride-hailing services like Uber and Lyft weakened the link between being in a car and owning that car, helping set the stage for a day when actually driving that car falls away too. In 2015, Uber poached dozens of scientists from Carnegie Mellon University—a robotics and artificial intelligence powerhouse—to get its effort going.

After a few years, the technology reached a point where no automaker could ignore it. Companies like Ford, General Motors, Nissan, Mercedes, and the rest started pouring billions into their own R&D. The tech giants followed, as did an armada of startups: Hundreds of small companies are now rushing to offer improved radars, cameras, lidars, maps, data management systems, and more to the big fish. The race is on.

Let’s start with the question you definitely want to ask: When will self-driving cars take over? Answer: wrong question. The autonomous vehicle is not a single device that someday will be ready and start shipping. It’s a system, a collection of inventions applied in a novel way. And, remember, the advance of the original car was constrained and shaped by forces like the growth of the road network and the availability of gasoline. The takeover of the self-driving car will depend on a new set of questions—the questions you should be asking.

When will self-driving technology be ready? That may, improbably, prove the easiest bit of making this real for the people whose lives it will affect. The hardware, to start, is mostly there. Radars are already cheap and robust enough to build into mass-market cars. Same goes for cameras, and the artificial intelligence that turns their 2D images into something a computer can understand is making impressive strides. Laser-shooting lidar is still a bit pricey, but dozens of startups and major companies are racing to bring its cost to heel. Some have even figured out how to use their photons to detect the speed of the things around them, a potentially key capability. Chipmakers like Intel, Nvidia, and Qualcomm are pushing down power requirements for these rolling supercomputers, while companies like Tesla are making their own chips.

The real job is to endlessly improve the software that interprets that sensor data and uses it to reason about how to move through the world. The key tool for doing that perception work—seeing the difference between a stray shopping cart and a person using a wheelchair, for example—is machine learning, which requires not just serious artificial intelligence chops but also gobs upon gobs of real-world examples to train the system. That’s why Ford and VW invested a billion dollars into artificial intelligence outfit Argo AI, why General Motors bought a startup called Cruise, why Waymo has driven 20 million autonomous miles on public roads (and billions more in simulation). Safe driving requires more than just knowing that a person is over there; you also have to know that said person is riding a bicycle, how they’re likely to act, and how to respond. That’s hard for a robot, but these budding Terminators are getting better, fast.

But are they getting better fast enough? In March 2018, a self-driving Uber Volvo XC90 operating in autonomous mode struck and killed a woman named Elaine Herzberg in Tempe, Arizona. The crash raised a number of suddenly pressing questions about testing autonomous vehicles on public roads. Is the tech actually ready? How should regulators handle this weird in-between moment, when the robots are good but not good enough? Should these vehicles really be tested on public roads? In the end, federal investigators blamed an inattentive safety driver, Uber’s flawed safety systems, and country and state regulators for the crash. But the questions raised by the incident still linger. That’s especially true as progress on the technology appears to have hit a speed bump, with many leaders in autonomous vehicle tech missing their self-imposed deadlines for commercial service.

Meanwhile, a less capable version of the tech is already on the market. Cadillac Super Cruise, Nissan ProPilot Assist, Ford BlueCruise and Tesla Autopilot all keep a car in its lane and a safe distance from other cars, allowing the people behind the wheel to take their hands off it. In 2018, Tesla debuted a feature called Navigate on Autopilot, which gives its cars (including those already on the road, thanks to an over-the-air software update) the ability to change lanes to get around slower drivers or to leave the highway when it reaches its exit. Yet the human driver is required to keep paying attention to the road and remain ready to take control if needed. That's because these systems are not especially capable: They can't see things like traffic lights or stopped firetrucks.

The problem is that humans are not especially well suited for serving as backups. Blame the vigilance decrement. And as these features proliferate, their shortcomings are making themselves clear. At least nine Tesla drivers in the US have died using the system (, and a federal safety board has criticized Tesla for making a system that's too easy to abuse. CEO Elon Musk has defended Autopilot as a life-saving feature, but even he doesn't use it properly, as he made clear during a 60 Minutes interview. Moreover, the main statistic he has used to defend the system doesn't hold up, a Tesla "safety report" offers little useful data, and it's not clear, anyway, how to produce more reliable numbers—or smarter systems.

Next question: Can we build and operate these things en masse? The huge automakers that build millions of cars a year rely on the complex, precise interaction of dozens or hundreds of companies, the folks who provide all the bits and bobs that go into a car, and the services to keep them running. They need dealers to sell the things, gas pumps or charging stations to fuel them, body shops to fix them, parking lots to store them. The folks who want to offer autonomous vehicles need to rethink interactions and processes built up over a century. Waymo has partnered with Avis to take care of its fleet of driverless minivans in Arizona, and it’s working with a startup called Trov to insure their passengers. GM is rejiggering one of its production plants to pump out Chevrolet Bolts without steering wheels or pedals. Lidar maker Velodyne opened a “megafactory” in San Jose where it says it could make a million units a year if it needed to. Federal regulators are considering ways to certify vehicles that don’t conform to safety and design standards written with human drivers in mind. Various would-be providers are drawing up plans for operations centers, where humans can keep track of their robofleets and cater to customers or cars in need. Legislators and public officials at all levels are racing to keep up and keep control of their streets. Chandler, Arizona—home to Waymo's base in Arizona—the fire, police, and planning departments have hustled to prepare.

And it’s not if these things will be deployed, but how. To start, forget the idea of owning a fully self-driving vehicle. The idea of a car that can handle any situation, anywhere you want to go, is decades off. Instead, expect to see these robocars either debut as highway-spanning trucks or in taxi-like fleets, operating in limited conditions and areas, so their operators can avoid particularly tricky intersections and make sure everything is mapped in excruciating detail. To take a ride, you’ll likely have to use predetermined pickup and dropoff points, so your car can always pull over safely and legally. Meanwhile, the people making these cars will be tackling knotty, practical questions. They’ll be figuring out how much to charge so they can recoup the R&D costs, but not so much to dissuade potential riders. They’ll wrangle with regulators and insurance companies, and what to do in the inevitable event of a crash that brings in the lawyers and legislators and safety advocates. And then, they’ll have to figure out how to expand—which is when the real competition begins. Ford and Waymo and GM and Aurora are all starting their services in different cities—and their trucks on different highways in the Southeast—but now they're fighting for turf. You know how fiercely Uber and Lyft fight for market share today, tracking drivers, trying to undercut each other, and piling up promotions to bring in riders? Now imagine that same fight with several times more competitors.

Here’s the question everyone should really be asking: How will this technology change your life? Well, your ride to the airport will get cheaper and safer. Your pizza will show up in a human-free robot, no tipping required. Your highway commute will become less of a drag. You might get blasted with ads tailored not just to you but to where you are and where you're going at any given moment. But that’s the basic stuff, the horseless carriage.

The truth is, it’s hard to imagine what people will do once vehicles can move about on their own, and once these things are so efficient that the cost of transportation falls precipitously. It’s easy to conjure up a dystopia, a world where robocars encourage sprawl, everyone lives 100 miles from their job, and sends their self-driving servants to do their errands and clog our streets. The optimists imagine a new kind of utopian city, where this technology not only eliminates crashes but integrates with existing public transit and remains affordable for all users. Like the internet, these vehicles will reflect some of our worse impulses, but also channel our best.

- Trucks Move Past Cars on the Road to Autonomy

Robotaxis, who? Amidst questions about the progress of driverless car tech, autonomous trucks appear to have taken the lead. The companies building them have raised a ton of money, and the places where they’ll operate—wide, well-marked highways, where vehicles generally travel at a consistent speed—are easier on the computer brain. It’s looking more likely that the first autonomous vehicle you’ll see IRL will be a hulking truck. - America’s ‘Smart City’ Didn’t Get Much Smarter

In a fit of mid-2010’s techno-optimism, the US Department of Transportation pledged $50 million to the mid-sized US city that could come up with the smartest, most viable plan to integrate tech into their residents’ lives. Columbus, Ohio, won, promising self-driving shuttles, transit apps, and on-demand rides for pregnant people. Six years on—and stymied by a global pandemic—the experiments are still experiments, a reminder that whizz-bang tech is not always a great starting point for civic improvement. - Uber Gives Up on the Self-Driving Dream

Uber, the ride-hail and delivery giant, invested more than $1 billion in autonomous vehicles. Former CEO, Travis Kalanick once argued that a tech that removed the costly human driver from behind the wheel was integral to the company’s survival. But in 2020, Uber sold its self-driving unit to Aurora. The move continues the consolidation in self-driving technology, as the process of creating safe, secure autonomous vehicles continues to cost more and take longer than prognosticators once believed. - Amazon Shakes Up the Race for Self-Driving—and Ride-Hailing

Does Amazon want to run a robotaxi service? The ecommerce giant sent a strong clue in the summer of 2020, when it acquired one of the most ambitious self-driving-car developers, the startup Zoox. Zoox envisions building a custom ride-hailing vehicle from the ground up, one that (if we’re being honest here) looks a little like a toaster. While autonomous tech certainly could help Amazon vans deliver all its packages on time, Zoox has continued its work on robocars. - Waymo's So-Called Robo-Taxi Launch Reveals a Brutal Truth

This was the moment many were waiting for, when Waymo, the company born as Google's Self-Driving Car Project and widely hailed as the industry frontrunner, would launch its robocars in a commercial taxi service. The reality was underwhelming: Only a subset of people already enrolled in Waymo's Early Rider program got to participate, and safety operators will remain behind the wheel for the time being. It's the best evidence yet that making the truly driverless—and truly safe—car is among the greatest technological challenges of our age. - A Not-So-Sexy Plan to Win at Self-Driving Cars

While the big names in this space—Waymo, Ford, General Motors, Uber—are going for ubiquity, smaller players have already moved to carve out their own niches. May Mobility, for example, is running or will soon launch (human-supervised) robo-shuttles in Michigan, Ohio, and Rhode Island. “Our sales pitch is not that we are autonomous,” CEO Edwin Olson says. “It’s that we provide a better level of service and we’re solving real transportation problems.” - Burger King's 1-Cent Whopper Gives a Taste of the Robocar Future

Burger King's oddball fast food gimmick—drive to a McDonald's, get a coupon for a one-cent Burger King Whopper—won't seem so strange once robots have taken the wheel. Depending on what sort of service you take (and what you're willing to pay for it), you might be blasted with ads tailored to who you are, where you are, where you're going, and how you're feeling. Creepy, right? - Plus! Waymo's robotrucks and more WIRED self-driving-car coverage.

Last updated September 8, 2021

Enjoyed this deep dive? Check out more WIRED Guides.