Nappies aren’t your typical warning sign – but a new move by a Japanese diaper company has sparked fresh concern about the country’s future.

Oji Holdings, a Japanese nappy manufacturer, announced that it is stopping making nappies for babies. Instead, it will turn its attention to adult diapers.

The reason? It’s all to do with the country’s ageing population.

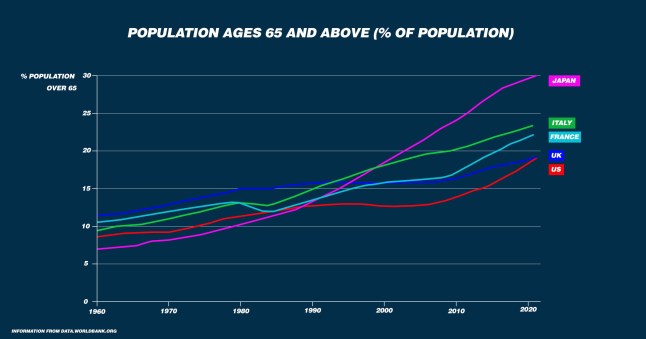

Japan has the second oldest population in the world, after the wealthy microstate of Monaco.

A combination of increasing life expectancy and declining birth rates have led to a huge shift in the population makeup of the world’s third-largest economy.

In short, there are fewer young people, and a lot more older ones.

Is this something that Japan – and the rest of the world – should be worried about?

Why are baby diaper sales declining in Japan?

Oji Holdings said that it was switching from selling baby nappies to sanitary products for adults.

In 2001, the company made 700 million infant nappies each year. Today, that’s dropped to 400 million.

A spokesperson for the company said that Japan’s falling birth rate was one of the factors behind the decrease in nappy demand.

It’s not the first time that a Japanese nappy company has felt the impact of a changing population.

In 2011, Unicharm, Japan’s biggest nappy manufacturer, said that its adult diaper sales had exceeded baby diaper sales.

Japan’s fertility rate, which the average number of children per woman, is 1.3.

Fertility rates need to be at 2.1 or higher to be at ‘replacement level’, which means that the population is stable.

There were an estimated 800,000 babies born in Japan in 2022, which is the lowest number in the country since the 19th century.

The cost of living is one factor at play. A 2021 survey found that 53% of respondents in Japan were concerned about the high cost of raising children.

Some traditional domestic gender roles still persist in Japan, which could also have a role, as some women might not want to quit their jobs to take on housework and childcare.

Stuart Gietel-Basten, Professor of Social Science and Public Policy at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, tells Metro.co.uk that changes to business models in response to changing populations is ‘inevitable’.

‘It’s just responding to a new reality, and if you don’t respond to that new reality, you’re going to get left behind,’ he says.

What’s happening with Japan’s ageing population and should we be concerned?

It’s not just the decline in the number of children that’s having an impact on Japan’s population, though.

A rising number of older people – largely thanks to increasing life expectancy – is breaking population records.

One in ten people in Japan are aged 80 or older.

It’s got one of the longest life expectancies in the world, after Monaco, Hong Kong and Macau.

While that sounds good, the country’s politicians have warned that it could have far-reaching consequences.

‘Japan is standing on the verge of whether we can continue to function as a society,’ Japan’s Prime Minister Fumio Kishida said in a speech in January last year.

The country has a population of 125 million, but researchers predict that that could fall to 53 million by the end of the century.

What challenges come with ageing populations?

One reason that ageing populations are a concern is because they can put pressure on a country’s healthcare system.

There are more older people to care for, but less young people to do so. Higher public spending on health might be needed to deal with the growing demand for care.

An ageing population can have an impact on a country’s economy, too. As well as a bigger demand for pensions, a shrinking working-age population could lead to worker shortages, which might slow down economic growth.

Experts have warned that the manufacturing sector could be particularly hard hit.

Meanwhile, the proportion of the population aged over 65 could rise to 34.8% by 2040.

In 2018, the number of people older than 64 surpassed the number of children under 5 years old for the first time ever.

The issue is at the forefront of public imagination. Last year, a Japanese movie called PLAN 75 told the story of a dystopian world where the Japanese government offers a euthanasia programme for the over 75s.

Professor Gietel-Basten says that low levels of migration in comparison to other countries have also played a part.

About 3% of Japan’s population is foreign-born.

However, he adds that Japan’s immigration has been increasing recently.

He says that a ‘silver economy’ could emerge in response to the ageing population, where goods and services are developed specifically for older people.

‘Older people who are now, in many countries, healthier, wealthier, highly skilled, than perhaps they were 30, 40, 50 years ago, maybe they have more savings to be able to spend and consume new goods.’

What is Japan doing to tackle its ageing population?

The Japanese government has pledged to double its budget for child-related policies, promising to spend around 20 trillion yen (around £110 billion) on measures to encourage couples to have children.

In February, the government approved plans to increase monthly child benefits for families and increase the eligible age cap to receive the benefit from 16 to 18.

Families receive 10,000 yen a month, which is around £52, for each of their children. However, in a bid to encourage couples to have larger families, parents will receive 30,000 yen for a third child, the equivalent of £150.

The government has also set up plans to bolster the country’s childcare sector.

Will this be an issue in the UK too?

Professor Gietel-Basten says that the situation in the UK is different from Japan, thanks to a number of factors.

He said that our higher fertility rates and immigration means that our population is ageing more slowly. However, he adds that age is just one part of the demographic picture.

‘Demography isn’t everything, and our health situation, our life expectancy, our diet, and other aspects of wellbeing, are not as great as Japan’s,’ he says.

More Trending

‘Just because one country is older than another, doesn’t necessarily mean that they should be more or less worried, because it is the institutional, socio-economic, political systems that are just important.’

In 1990, people over the age of 85 made up 1.6% of England’s population. By 2020, this had risen to 2.5%.

In the next 25 years, the number of people in England over the age of 85 will double to 2.6 million.

The proportion of people over 75 with long-term health conditions in England has risen, which means caring for our ageing population is becoming more complicated. However, more older people than ever are able to live independent lives.

MORE: Health pills which all share one ingredient linked to five deaths

MORE: Man dies after his suit jacket got caught in an escalator

MORE: I thought I was dying but I was actually eight months pregnant