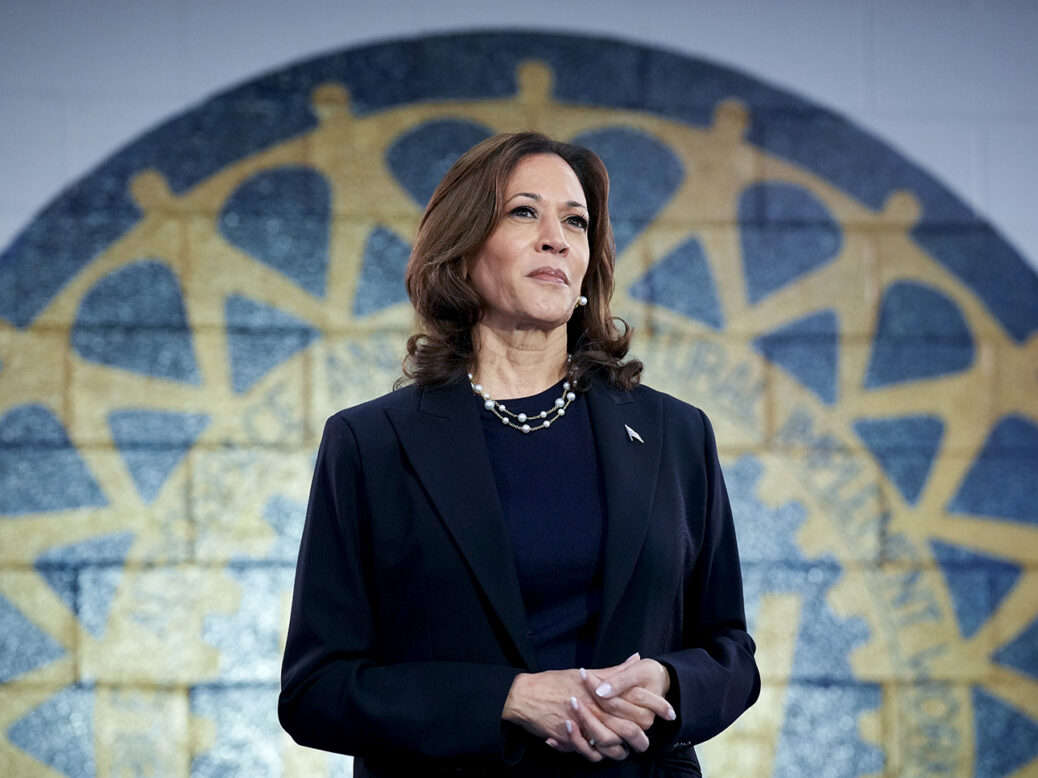

Democrats elated by Kamala Harris’s candidacy for president and further buoyed by the apparent strife inside the Republican campaign are no longer so panicked over the odds of beating Donald Trump in November. But as the dust settles from this summer’s dramatic events – the withering of Joe Biden, the assassination attempt on Trump, the selection of JD Vance as Trump’s running mate – the American public faces an odd rerun of past elections. As we’ll surely see at the Democratic National Convention in the coming days, Harris is betting on the fresh contrast she provides with Trump. Yet the themes she and her party have embraced are the same as those from 2016 and 2020: to save democracy and prevent Trump’s wreckage of U.S. institutions. Gestures to cheque book issues aside, Harris does not yet seem ready to campaign as a populist who would challenge the country’s economic elite.

That approach leaves an opening for a reorganised Trump-Vance ticket which prioritised economic discontent in the swing states that will determine the election. And it comes at a time when parts of the Republican Party, once synonymous with big business and free-market dogma, are more aggressively trying to establish a pro-worker image. Democrats, of course, dismiss the GOP’s threadbare commitments to labour, highlighting Trump’s anti-worker rhetoric, preference for yet another corporate tax cut and the deregulatory zeal of Project 2025, the alleged blueprint for a second Trump administration. Yet Harris cannot coast on America’s relatively strong economic performance and low unemployment rate under Biden. Anxiety over living costs is pervasive, and while Biden’s sweeping industrial strategy was bold it was not well understood by the public.

In fact, Harris’s window to take a firmer stance on questions of economic power may be quickly passing. Her pick of Tim Walz, Minnesota’s progressive Democratic governor, has been well-received across the party base, and it is widely thought that his record of pro-labour reform will quell doubts about the ticket’s priorities. But Walz’s primary purpose is to shore-up the “Blue Wall” in the Midwest, not shape campaign promises. Harris has shown a willingness to explore some radical ideas, not least with talk of banning grocery “price gouging” mooted in a speech in North Carolina on Friday. But as chatter persists over whether she might abandon Biden’s more populist initiatives under pressure from Wall Street and the donor class, the fear among economic progressives is that Trump’s relentless “America first” message will, in the final stretch, once more eclipse the Democrats’ reflexive appeal to values and identity politics.

This may surprise those who believed the Democrats had emerged a bolder and stronger party after Trump’s chaotic term. Many supporters hoped Biden’s gamble on a developmentalist agenda would dampen Trump’s strength with working-class whites and return some of them to the Democratic fold. But despite a suite of investments directed toward America’s rust belts – as well as some important steps toward protecting workers and consumers from corporate abuse – Biden’s policies are slow to catch on in places that continue to weather plant closures, higher poverty rates, and declining family formation. The impasse has vexed progressive Democrats otherwise emboldened by their legislative accomplishments and newfound faith in Harris. Biden may be heralded by the commentariat as the first “post-neoliberal” president, but Bidenism hasn’t crystallised into something greater than the sum of its parts, let alone a platform that could realign the electorate on the scale of the New Deal or Reagan revolution.

The mandate to cement a new order in this election is thus up for grabs. Still, there are reasons to doubt that either Trump or Harris, short of an electoral sweep, will turn post-neoliberalism into something more definitive. The tenuous agreement between Democrats and Republicans on the need to reindustrialise parts of America and limit foreign competition proves the link between Trump and Biden. But it is also a reminder that American political economy is stuck in an interregnum, with only halting progress on labour rights, anti-trust enforcement, and family policy. Though hyper-globalisation continues to founder, neither party has offered a transformative vision that might decisively build on what Biden has started.

As the 2024 party convention bids farewell to his leadership of the Democratic Party, it is still remarkable how much Biden, a career centrist, broke with 40 years of economic orthodoxy. Hailed as a sea change, “Bidenomics” nevertheless failed to earn high marks from voters. Some of this can be attributed to a post-pandemic malaise and inflation’s disproportionate effect on working-class families. For many Americans, tight labour markets did not translate into significantly higher pay packets. Increased costs for regular goods and services, as well as interest rates that have spiked debt loads and cut into savings for major life purchases, have consequently led a percentage of black men, Latinos, and swing voters to favourably reassess Trump’s term.

There were also conflicting expectations of what a Biden presidency would represent. Alert to the despair and degradation that helped fuel Trump’s rise, Biden tried unsuccessfully to be both the elder statesman and a transformational figure. Of course, he was neither able to deliver the “return to normalcy” his campaign promised nor raise overall living standards in an efficient manner. Rhetorical invocations of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal equally fell flat. While Biden’s agenda is the closest the Democrats have come in decades to channelling the Rooseveltian spirit, it often seemed that a geopolitical project to secure key industries for the energy transition took precedence over affordable housing and a stronger welfare state.

This accentuated the disconnect between the macroeconomic picture touted by the president’s allies and Americans’ day-to-day perceptions of their well-being. Meanwhile, many on the left, infuriated by legislative compromises with centrist Democrats, argue that Biden didn’t go far enough – or picked the wrong priorities altogether. Perhaps most important, though, Biden proved incapable of crafting a persuasive narrative about how his policies would forge a new basis for shared prosperity.

However maddening it may be for stalwart Democrats, such shortcomings contrast poorly with Trump’s enduring power to shape perceptions of the country’s direction and win over past critics (including, most notably, Vance). Indeed, the flimsiness of Trump’s “populist” ideas has not stopped him from playing the insurgent against the establishment nearly a decade on from his first campaign. Of course, Trump’s preternatural ability to do so may be reaching its end, given his flailing attacks on Harris and other progressives such as Shawn Fain, the popular leader of the United Auto Workers. Most Democrats, however, have yet to truly skewer Trump and his core donors as the economic royalists they are. As it has countless times before, the party is instead vacillating over whether it is in favour of a bold social-democratic vision or something more restrained and technocratic.

These dynamics have a created a double bind for Democratic leaders: even as they have tried to resurrect an activist state on behalf of the left behind, they are also the party of “conserving” the gains from globalisation and the modern urban affluence which sprung from it. Hence the party’s Janus-faced approach to populism. The reality is that the Democratic Party – which for much of the 20th century drove a policy agenda in Washington based on taming corporate power, industrialising the American South, and helping trade unions – has struggled to move beyond Bidenism’s reactive impetus. If Biden’s substantive application of Trump’s critique of free-trade, China’s geoeconomics, and globalisation took the political world by surprise, Trump nevertheless holds the advantage of having set the terms of the debate.

Along with Trump’s unique political instincts, this has bolstered the Republican Party’s ongoing effort to refashion itself as a vehicle for blue-collar Americans and blunted, in key locales, Democratic attacks on other salient issues. That strength confounds Democrats who believe they have meaningful solutions for downtrodden communities. They miss, however, the way the populist revolt behind Trump shredded the central, if oversimplified, narrative of American politics: that Republicans invariably serve the most privileged classes and regions, while Democrats champion wage-earners and those who have fallen on hard times.

On key metrics, this is no longer the case. The counties that voted for Biden in 2020 and Hillary Clinton in 2016 produced a majority of the country’s GDP, and Democrats now represent a majority of the wealthiest districts in the House of Representatives. Incremental reforms in coastal blue cities and states, meanwhile, have done little to dent the perception that their governments cater to the winners of the knowledge economy. Appeals to a shared multiculturalism between these elites and the urban underclass arguably hold less sway than when Trump first arrived on the scene. Despite the depth of the country’s polarisation and the pull of negative partisanship, working-class “dealignment” appears to be accelerating. Like the “Reagan Democrat” of the late 20th century, the proverbial “Obama-Trump” voter is a greater phenomenon than most analysts realise.

So, what to make of the GOP’s play for the working-class vote? Its sincerity has been gainsaid by progressives for reasons as sound as they are obvious. Still, the party’s core ideology can no longer be equated with the neoconservative globalism of George W Bush nor is its support so strongly anchored in the country club suburbs. While most Republicans still only offer tepid remedies for the problems that ail post-industrial America, the fact that they represent an increasing share of low-income Americans underscores why influential voices on the right believe that Vance, with his hardscrabble background and populist rhetoric, symbolises the party’s future. The implicit theory is that, within the next few election cycles, the anti-establishment groundswell will at last force the GOP to meet the unsatisfied economic demands of their base. Trump, in this more calculated reading, is simply a vehicle to a new political alignment, not an object of blind reverence.

In some ways one can see why advocates of Republican populism believe they still have the wind at their backs – and that more has changed in the U.S. party system than progressives realise. In particular, they point to ideas circulated by “New Right” think tanks such as American Compass and overlooked bipartisanship in Congress as proof the GOP’s rising stars want to promote ideas once associated with New Deal liberalism: fair competition and consumer rights, collective bargaining, family subsidies, and long-term investments in regional development. A post-neoliberalism of the right, in other words, would set parameters for market behaviour and alleviate economic pressures on working families – just don’t call it redistribution.

By any reasonable measure, Trump’s GOP continues to fall short of these lofty expectations. Besides the usual stale mix of tax cuts and deregulation, the centrepiece of the Trump-Vance ticket’s economic platform is a universal baseline tariff to stoke domestic industry. Tariffs and other trade restrictions, as the Biden administration has conceded, are part of the tool kit to coax fixed investment. But on their own they are hardly enough, in an economy flooded with precarious gig work, to correct regional and structural imbalances and dramatically lift wages. As before, the populist wing may wager that the true potential of Trumpian economic nationalism can be measured by the backlash it sparks among elites. But while the lack of support for the ticket among major business executives has generated considerable noise in recent weeks, this discomfort speaks more to the incoherence of Trump’s vision than any purported radicalism on behalf of workers.

One pathbreaking idea on hand is to devalue the dollar to boost manufacturing exports and curb financialisation – a position once advocated by Elizabeth Warren, the progressive Democratic senator from Massachusetts and former presidential candidate. That would certainly mark a breach with a regime that still favours a strong currency, one of the pillars of the old Washington consensus that Biden has left intact. In combination with the inflationary pressures that extended tax cuts and higher tariffs would likely generate, such action might compel Republicans to support other interventions they would normally reject in order to stabilise the purchasing power of working households. Suffice to say, this is a major hypothetical not backed up by where most of the GOP stands on regulating the market.

The GOP’s manifest limitations on these fronts reinforce the view that the post-neoliberal consensus remains inchoate. Republicans aren’t willing to go much further than tariffs and subsidies for innovation in the “defense industrial base”, and in this sense are much closer to the actual Reagan paradigm than either the populists or market fundamentalists would like to admit. Many Democrats who have the vice-president’s ear, meanwhile, seem keen to bracket Bidenism – to limit their horizons to being stewards of economic growth whom high-profile business leaders can trust. Although a President Harris would likely preserve aspects of Biden’s trade and industrial policies for national security reasons – another roundabout concession to Trumpian populism – the appetite to do more on labour and welfare policy could easily dissipate, particularly if pro-business moderates are seen as providing her margin of victory in November.

The question of what post-neoliberalism ultimately entails – of whom must be appeased, which policies must be advanced, and what can be scrapped – thus hovers over both parties. As the country staggers through this transitory period, it may be more apt to say both parties have merely rejected “Rubinomics”, the set of policies named after Robert Rubin, Bill Clinton’s Treasury Secretary. A governing philosophy which extolled maximum capital mobility, trade liberalisation, and fiscal austerity is finally obsolete. But what follows “peak globalisation” is less certain.

This brings us to a paradox of the 2024 election. As high as the stakes are, there is a case to be made that American politics is headed toward further stasis, that talk of an epochal realignment in terms of class, region, and ideology is premature – regardless of who wins. Until the economy suffers a more existential shock than what we’ve seen this century, post-neoliberalism may be more about propping up existing coalitions than reckoning with American capitalism as such.

Given Harris’s evident momentum, she can afford to risk more. Trump’s economic populism, like the GOP ticket itself, has deflated remarkably in the few weeks since the Republican National Convention, when it briefly seemed that Trump would achieve his long-sought commanding victory at the ballot box. A compelling Democratic agenda, therefore, must not only draw a contrast based on Trump’s deficits – moral and otherwise. It must declare how a Harris administration will nourish economic democracy in the US and radically curb the abuses and fraud which are inflicted upon so many struggling families. By the end of her nomination speech next Thursday, we’ll know if Harris is taking on more than Trump.