What does it take to win Survivor? You may find it bizarre that, almost a quarter-century after the CBS show premiered — essentially inventing the reality-competition genre in the process — the question still matters. But it does to its fans, and surprisingly, there are more than there have been in a long while. The show will never again reach the mass-audience heights of its first season, when nearly 52 million Americans glued themselves to their sofas to watch a corporate consultant named Richard Hatch become reality TV’s first-ever triumphant gay villain. But today, hits are measured differently, and Survivor, by any metric, remains a big one. This past summer, it received an Emmy nomination for Outstanding Reality Competition Program, its first recognition in that category in 17 years. And boosted by a viewership that swarmed to the series in search of soap-operatic binge viewing (short arcs, big characters, noisy conflict) during the pandemic, the series just finished its 46th cycle as the No. 1 show on prime-time network television in several younger demographics.

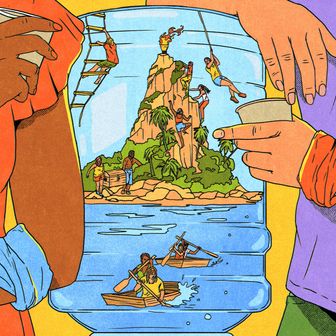

Over the past 24 years, the premise of Survivor has remained the same: Sixteen to 20 contestants cosplaying castaways on a remote locale are put through a series of challenges while starving, getting rained on, and forging friendships, alliances, marriages of convenience, and bitter hatreds. They’re eliminated one by one through secret ballots cast by their fellow players at a “tribal council” at the end of each episode until almost the entire tribe is gone and the one who’s left is a million dollars wealthier. What has changed is the audience: The show now attracts a new generation of fans preoccupied with the question of who obtains things fairly and who doesn’t, whether that manifests in nepo-baby discourse or in declaring in every election cycle that corporatism, the media, and the two-party system all reward the wicked. For this audience, Survivor has proved a rich text.

In This Issue

More From

the Television Issue

See All

There have always been, broadly speaking, two ways to win Survivor. The first route to victory is to demonstrate an exceptional skill — to be the most popular, the most manipulative, the most athletic, the most strategic, the most adept at managing relationships. These are the winners who make for an exciting narrative arc. One of the show’s pleasures comes from watching characters who embody these different strengths face off against one another and seeing which quality the final jury, composed of eliminated contestants, will choose to reward. In one season, a player’s pure charisma may trump another’s carefully plotted, chesslike strategy, as when an incredibly winning cattle rancher named J. T. Thomas beat his closest ally, Stephen Fishbach (another corporate consultant), in Survivor: Tocantins. In a different cycle, brains and rationality might prevail over preternatural athleticism, as when the hyperanalytical Yul Kwon beat Ozzy Lusth in Survivor: Cook Islands despite the latter being one of the most physically dominant players of all time.

The other way to win is to strive assiduously to be none of those superlatives; to be semi-ignored as, say, the third best at everything, coasting under the radar as the bigger noisemakers to your right and left topple. Take, for example, the most recently concluded season, whose final stretch featured a cross section of classic player archetypes. There was the strategist: Charlie Davis, a law student who, at every stage, assessed his chances and plotted his moves with the precision of a mathematician. There was the chaos agent: Quintavius “Q” Burdette, a Realtor who cheerfully sowed paranoia, convinced his fellow players to backstab one opponent after another, and went out in a blaze of glory. Then there was the winner, a hair-salon owner named Kenzie Petty. Kenzie was not, by any measure, the strongest or most aggressive player of Survivor season 46. She wasn’t the most strategic or the most charismatic. She was just … a player, who won by hanging on until she was the last leaf on the tree.

Kenzie was far from the first contestant in Survivor history to earn her million dollars that way, and her victory, though unexciting, was not illegitimate. After all, the show is called Survivor — you don’t need to triumph; you just need to persist. The truth is that those who collect the check are rarely those who look like they’re going to be the winner four episodes in: To take it all, you have to exhibit an unlikely mix of traits — likable, calculating, aggressive, dangerous, sincere, manipulative — while appearing just unthreatening enough that, at tribal council, you are never anyone’s priority to eliminate. There are memorable exceptions. Tony Vlachos, a fast-talking cop who bulldozed his way to victory in the 28th cycle (Survivor: Cagayan — Brawn vs. Brains vs. Beauty), was nobody’s idea of a subtle player. His gameplay (which included constructing a secret spy shack to eavesdrop on conversations, taking off into the woods to find hidden idols, and deceiving and double-crossing close allies) is remembered as the most over-the-top in Survivor history, and he tended to announce his plans as intemperately as a James Bond villain. The spectacle his ascent offered viewers was both yell-at-the-screen maddening — couldn’t the other players see what they were allowing to happen?! — and undeniably great TV.

Today, it’s hard to imagine Tony making the final four. Modern-age Survivor is increasingly tailored to the Kenzies of the world. The most frequent complaint I hear about the show these days is “People win for no reason now.” And “no reason” is worse than a bad reason; a winner like Tony who makes some of us howl in dismay is better for the game’s long-term popularity because we’re at least engaged. A winner whose main skill was shrewdly evading attention often makes for a shrug of a season — and lately, it’s sometimes hard to tell which of those wins can be credited to low-key manipulation and which are mere accidents.

Grievances about the randomness of outcome are closely connected to a broader dissatisfaction with the “New Era” of Survivor — a term the show itself uses to describe the six cycles that have aired since it returned in the fall of 2021 after COVID shut down production and knocked it off the air for 16 months. If, like me, you haven’t watched for a long time, the show’s New Era changes feel initially mild but cumulatively seismic. Survivor now unfolds over just 26 days, not 39. Host Jeff Probst (yes, still) is, at 62, less a drill sergeant than a warm, amused, disarming eminence, aware of his status as a super-celeb for the often decades-younger contestants. Those contestants tend toward the extroverted and crybabyish — the most grating of them are a combination of every mean joke ever made about Gen Y, Gen Z, Gen TikTok, and Gen Influencer. They are not stoic. Rather, they start sobbing in the season premieres — they miss their families (I’m sorry — were they conscripted?), they didn’t think this would be so hard, they’re tired, they’re hungry — and they don’t let up. They have food allergies and anxiety disorders and other issues that surely would have excluded them in 2000. Sometimes they quit because, you know, who needs this shit?

The most jolting and controversial change, though, is in the gameplay itself. The show has long featured immunity idols — tokens that, if a player chooses to deploy them, provide protection against being voted out for one ballot cycle — but there are now so many per season that a contestant can turn up at tribal council toting two or even three. In addition, the producers have introduced several “advantage” tokens, each of which comes with its own complicated set of rules: one gives you immunity but only in conjunction with someone else; another offers a one-in-six chance of immunity; another provides an extra vote. These are hidden near the campsites to be hunted down and pocketed by enterprising players. The effect has been to transform the game from its original survival-of-the-fittest mandate into a contest that feels crafted for those raised on video games in which everyone is essentially a lone wolf and the goal is to amass as many power-ups as possible on your personal journey. These advantages have a deus ex machina quality. Rather than nourishing the larger narrative, they can make the season feel like little more than an accumulation of disconnected bits of luck. The producers already seem to be pulling back on those gimmicks, and not a minute too soon.

These adjustments have shifted the competitive edge slightly away from athletes and alphas (which is welcome) and toward “students of the game” (at best a mixed blessing). All reality series lose their virginity this way shortly after their introduction when they become populated by players who have watched the show rather than by those who essentially invented it. But more than most, Survivor’s casting team has left a perhaps unhelpful amount of room for the Survivor geek — the guy (it’s usually

a guy) who seems to have mentally downloaded every season, contestant, and elimination vote and can cross-reference them at will.

High ratings notwithstanding, many fans are frustrated by the new approach. For one thing, all those extra tokens and trinkets make self-protection — the least interesting of all the necessary Survivor skills — the one that matters most. And by privileging a player’s ability to insulate themself from the ramifications of interactions with other competitors, the rules all but eliminate a long-standing pleasure of the series, namely, Survivor as metaphor. For many seasons, the show served as a window into how gender, race, personality, strength, intelligence, and social skills can all play into a determination of who comes out on top in any given power struggle. And the most memorable seasons turned the game into a microcosm of real-world issues in ways that were sometimes acutely discomfiting — subsurface racism has been such an ongoing problem that a few years ago, CBS mandated that half of all its reality casts would henceforth be nonwhite — and sometimes deeply satisfying: The all-time classic 16th season, Survivor: Micronesia, became a gender-wars parable in which an ad hoc female alliance that called itself the Black Widow Brigade systematically took down every man in the competition and ended up as the final four.

As far as narrative potential goes, recent seasons mostly bring to mind the limited dramatic interest of wonkish gameplay for its own sake. Too often, New Era players attempt to finesse their way to the finish line not by managing the ideal combination of classic Survivor skills but by tediously attempting to work the system they’ve studied on television. Contestants make decisions for the express purpose of adding to their “résumés” (a term that refers to a player’s list of big, shrewd moves that might impress the final jury) as if they were crafting college applications. They fret about likability, not their own so much as that of anyone who might beat them in a final vote on the basis of personal charm.

As a result, Survivor is now in danger of becoming primarily about the ability of contestants to navigate its increasingly byzantine set of rules. This has always been a built-in hazard: Unlike competition shows from Top Chef to American Idol, this one has offered only the merest lip service to the idea that it’s rewarding an objectively assessable talent; the only thing you have to be the best at to win Survivor is playing Survivor. You no longer get to the end by being the strongest or the most honorable or the most devious but by being the most Survivor-ish; if that’s a meritocracy, it’s a meritocracy for those who believe meritocracy is a scam. The series seems to have entered its Marvel Cinematic Universe phase: Like those movies, it has endangered its own vitality by becoming so entranced with its own arcane byways, procedures, and asterisks that they have become the primary driver of the narrative rather than ornaments to it. It is, in other words, threatening to become a show about nothing but itself.

At this point, the most radical thing the series could do is get back to the fire-food-and-fighting basics, consign those hidden-in-a-tree-stump idols and advantages to the dustbin, and play to its strengths. Better than any reality show out there, Survivor understands that all kinds of traits, from the inspiring to the dubious to the contemptible, will emerge organically from within a given group if all of its members want something badly enough. It’s why we watch. And it’s what the show needs to rediscover.

More From the Television Issue

- Lionel Boyce Is The Bear’s Secret Sauce

- The 2024 Streaming Power Rankings

- Can Industry Succeed Succession?