There’s a joke in the visual effects industry that goes like this: Someone hears you work on films, so they ask you, “What movie made you cry?” The artist will respond, “In theaters or in the office?”

The VFX industry is deeply broken. It exploits artists using short-term contacts, chases tax incentives across the globe, and creates an environment where production studios, especially an industry giant like Marvel, are treated with a deference that comes at the expense of the artists’ craft and mental health. VFX is a machine designed to destroy artists. And it’s working perfectly.

Across a series of phone interviews with sources within the visual effects industry who have worked on multiple Marvel titles, from Phase One up to as-of-yet unaired television shows, io9 heard a litany of complaints about working conditions that visual effects studios impose on their staff in order to meet the demands of their clients. All the VFX workers in this story are referred to by pseudonyms due to the relatively small size of the industry, and because they’re afraid of being blacklisted. io9 also made numerous requests to Marvel for comment, but as of publication time, they had not responded. This piece will be updated if they decide to reach out.

The bidding process is broken

In 2013 the visual effects studio Rhythm and Hues won the Academy Award for Best Special Effects for work on Life of Pi. (The studio was also nominated in the same category for Snow White and the Huntsman.) But just eleven days before winning the Oscar, the company was forced to declare bankruptcy.

“Essentially, partway through the movie, the director [Ang Lee] made a big change to the tiger [in Life of Pi], so Rhythm and Hues had to go back and redo almost all their work. And it cost them so much money to do so, and they were already working on such a thin profit margin, that it bankrupted them,” said David, a VFX artist. “So the studio literally went bankrupt just before they won the Oscar for Best VFX.”

However, another source, Jeff, who was involved in Life of Pi disagrees. Blaming any single person or decision would be reductive. “Client-side production (ie: Ang Lee, Producers, etc) put the show on hold partway through post production… because the third act of the film was being re-worked, and Toby Maguire’s role in it was being replaced as part of a series of reshoots.”

In a gamble that didn’t turn out, the founder of the studio, John Hughes, attempted to retain his staff and contractors during the pause rather than attempt to staff up again when work resumed. “I respect them for what they tried to do but, in hindsight, they avoided a small problem only to cause a monumental one in its stead. All of that being said, [Rhythm and Hues]’s collapse was due to a series of unfortunate circumstances and decisions, and no one show—even one as large and important as Life of Pi—was the single point of failure.”

Marvel Studios, like just about every other production company, hires studios to produce VFX. And in order to work for Marvel, or any of the five or so production companies out there that are offering big-budget VFX work that keeps VFX studios afloat, studios continuously underbid each other in order to appeal to an increasingly-small client base.

It works like this. First, the production company sends out a dossier of shots that need VFX work. Studios might get a shot description that simply reads “an alien spaceship appears.” A bidding producer at a studio will review those shot descriptions in order to create an estimate for the bid, but this is more of an art form than a science.

“It’s a race to the bottom,” David said. “Because when the big [production companies] say they need work done, [the VFX studios] undercut each other so much that by the time they finally get that contract, they’ve bid so low they’re lucky to break even. And so that forces these VFX studios to operate at very low margins.”

Why are we only hearing about Marvel?

Marvel is so prolific, and has so many projects going on, they have to hire dozens of studios at a time, all over the world. So, not only is underbidding happening based on domestic competition, but also based on the assumption that other countries will be exploiting labor loopholes and tax incentives.

“For example, the UK doesn’t have any paid overtime in any industry,” said H, a production coordinator, “and because they don’t have to legally pay anyone overtime, when they bid a show that might cost them $15 million to do the work, a UK studio might say, ‘Well, we’ll do it for ten.’ So if they rack up 200 hours of overtime a week in London, it doesn’t affect the bottom line… It’s not costing the studio any money to force you to work through this crunch delivery.”

A Senior VFX Artist, Sam, who has worked on six Marvel films across their career, agrees. “Those London companies are awful. All of the British companies that I’ve dealt with have been really brutal.”

Location-based tax incentives also drive down bids across the industry. If Marvel spends $10 million in a location with a 30% tax credit, the government will pay Marvel $3 million after the invoice is paid, so it only costs Marvel $7 million to purchase $10 million dollars worth of work from a VFX studio. (This is an oversimplification, but is, generally speaking, how it works.) So, instead of bidding $10 million for the shots, which is what it actually costs to produce the work and make a profit, a company without access to these credits will bid $7 million in order to underbid a studio located in a place with favorable incentives.

“I’ve seen the books,” said Hector, a VFX Artist. “Despite working on major motion pictures, the profit margins for these VFX houses are in the single digits.” And then, after all that, the VFX studios will bid for the next project… Probably another one of Marvel’s.

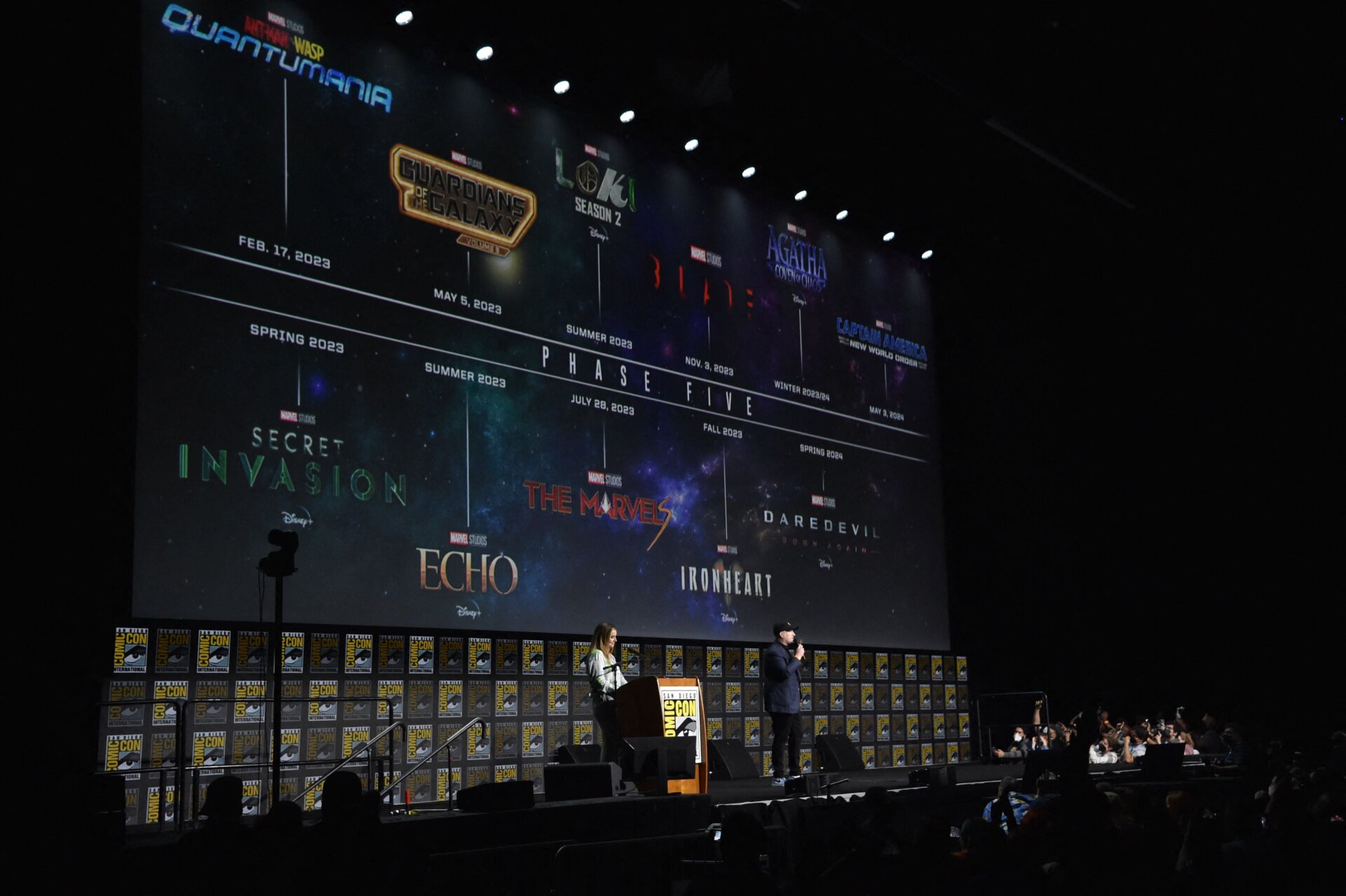

When Kevin Feige unveiled the massive film and television slate that would make up Phase Five, you could almost hear the collective groan coming from VFX artists.

A VFX artist, Jason, said that Phase Five was going to dominate a lot of his friend’s careers for the next decade. “You see all these timelines for films and just think… It won’t ever stop. The workload becomes agonizing at times… We’re all just sick and tired of superheroes.” But studios, he said, rely on superhero work–and Marvel–in order to make ends meet. “These studios keep feeding from the same trough because the work is so abundant, and [Marvel] needs so many people, and artists need jobs. Where do you think these studios are going to go?”

We’re hearing about Marvel’s treatment of VFX studios more than any other production company because there’s just so much of it, regardless of specific relationships to vendors. “Marvel has a different production team every single time,” explained Conrad, a production coordinator who has worked on multiple Marvel projects. “So sometimes you might have a really, really good working relationship with them, and other times you might not.”

From a dream job to a working nightmare

At first, working for Marvel was a passion project for a lot of artists. It was cool to get to work on Iron Man or Thor. Studios and artists gained a lot of clout with those films. This helped drive down the bid prices, especially during Phase One. David said that when he started working on Marvel projects, it was exciting. “I was still kind of nerding out a lot of times, getting to see these movies being made and being part of that whole process. But yeah, there are definitely quite a few long days” he chuckles, admitting to something that has become, at this point in almost every VFX artist’s career, very normal.

David describes Guardians of the Galaxy as being one of the favorite projects that he’s ever worked on. But even he agrees that Marvel’s process is inconsistent. “The worst was when Avengers: Infinity War and Endgame were coming out. They actually bumped up that release by a month but they hadn’t told us. I remember being on the floor with my team and one of my artists comes to me and says, ‘Hey, you see this?’ and he shows me the article saying Marvel bumped the release date up a month.”

Marvel failed to tell the VFX team working on the film that the release date had changed. David went to his supervisor, who also hadn’t heard anything about it. Marvel eventually got back to the studio and said that they had “forgotten” to tell them. “So we found out from a press release that we had one less month to work on all these shots.”

“[Marvel] is the worst example of a lot of the problems in the industry,” said Sam. “It would be one thing if sometimes it was really bad, sometimes it wasn’t… But with Marvel, it seems like every single time it’s the same thing. So, one, they tend to be as bad as you’re going to get and they’re consistently that bad.”

Hector recalled that during the last Marvel project he worked on, “from my very first day on the project, up until we delivered the shots, we were working overtime and weekends. It was just months of literally being nailed to my desk.” He laughed as he said this, almost like he hated to admit it.

“Even up until the last week or so they still weren’t sure what they wanted this gigantic set piece to look like. We were still doing concept art.” Hector said. Concept art is supposed to be the first thing you nail down before you start working on the pieces that will eventually be composited together to make up the shot. “And various parts of this sequence had already gone through the entire pipeline. You’ve got lighting renders, effects simulations, matte paintings, and animation.” All of this, ready to go, and Marvel still hasn’t approved concept art.

This isn’t a fluke; this is part of the process. Many sources stated that Marvel deliberately shoots their films in such a way that they are able to change details, both big and small, up until the very last minute. Very little is shot practically, and even the stuff that is practical goes through touch-ups. “When you get a plate of just someone’s face against a poorly lit screen, there’s really nothing you can do to make it look realistic,” explains H. A plate is the untouched frame, exactly what was captured on camera, mocap suit and all. “That’s something that never gets commented on. Everyone just goes, ‘Oh, the visual effects look shit.’ And I’m like, No, you should have seen the plate. You should have seen what we were given, because that’s what was shit.”

Sometimes changes will occur even up to the final days before the movie is set to be released. Conrad recalls that when “the first Doctor Strange movie came out, it didn’t actually have final VFX on it. They were still working on it after the movie had come out in the UK.” While the film premiered in Hong Kong on October 13, 2016, and opened wide in the UK on October 25, the VFX work wasn’t complete until October 28, when it was released in US theaters. With many production companies asking for more and more changes closer and closer to the delivery deadline, the individual artists at VFX studios are put under immense pressure, causing them to work massive amounts of overtime in order to accommodate these shifting goalposts.

“I didn’t have a day off for five weeks. And those were not eight-hour days. They were ten-plus-hour days,” recalled Sam, speaking about his experience working on a Marvel show. “And that was because they did a reshoot a month before the show was due. So we literally got shots in at the end of December for a show that was due at the end of January.”

These stories are common when you talk to VFX artists, and usually reach the same conclusion: Marvel suffers from a chronic lack of vision that comes from having an entire movie decided by a committee of people, from producers, to executives and directors, to Kevin Feige himself.

Erratic direction leads to erratic results

Feedback on dailies and sequences comes from all over the place, including executives and producers that aren’t in explicitly creative roles, H said. “I’ve had entire sequences get blasted apart by someone who shouldn’t even be a part of the feedback process. Like, why do you get an opinion on this?”

Sam’s had similar experiences. “You get producers that say, ‘I want to be involved in the artistic process,’ and you’re like–” he makes a skeptical noise, “I don’t ask to look at your spreadsheets, man.”

All of this input dilutes the vision, muddies the direction, and ultimately, cracks apart the production pipeline. As more and more people are brought in to provide input across many different studios and many different projects, the changes snowball across the entire project, causing hundreds, if not thousands of hours of work to be redone at any number of studios. All because someone didn’t like a shade of blue, or they needed to change a suit design to help toy sales.

Some VFX studios will push back on these changes more than others, and many sources noted studio culture was the deciding factor on whether or not artists had to deal with this kind of nitpicking from producers. “But in general that power dynamic is so skewed towards Marvel that they can ask for whatever they want,” Sam explained. “And then the VFX house has to just figure out how to make it happen.”

The lack of direction is the biggest, most consistent pressure point for many of these artists. Sam recalls a logo on a suit that he had to redo “almost every week.” Conrad recalls working on a shot for Marvel where they didn’t know what they wanted, so they asked the studio to make two versions. “And then we found out which version they picked when we saw the movie.”

Hector has seen massive sequences scrapped within a week of delivering shots that took two or three weeks to build out. “The entire vision will change completely,” he said. “And I get that. You want your directors to have control of the final product. But from the artists standpoint, you need a direction to go in. And Marvel has this very harsh way of communicating with the vendors where they’re very cynical and very, very rude. As if you should be lucky to be receiving constant revisions and notes from them.”

Sources also stated that this constant vision shift feels driven by the egomaniacal ability to demand changes and see them acquiesced to, rather than considering the kind of changes that will actually affect the story. “Nobody is holding Marvel accountable,” H said. “So they don’t care. They’re like, ‘Fuck you guys. We can make as many changes as we want and you just have to deliver it.’” These changes can be major: Sam described an incident where an actor was filmed in a practical suit and the studio decided it was the wrong suit. “And you have to replace their entire body and just leave their head in every shot.”

All this is done without adjusting the bottom-line of the bid, which means that studios usually can’t hire more artists during crunch time or else risk that single-digit profit percentage going into the red. Continually asking for adjustments, changes, and edits to the shots is called getting “pixel-fucked,” because the edits to shots become more and more minute until artists are literally editing a single pixel in a shot and sending it off for re-approval. And every time an artist gets pixel fucked, it usually ends up costing the VFX studios money.

The erratic direction of Marvel movies leads to erratic results. That’s why you see incredibly sharp and realistic VFX work in one scene, and then two minutes later, the VFX work looks choppy and rushed. Because in a lot of cases, it is. All the VFX studios that Marvel hires are capable of producing incredible work, but very few are given the opportunity to do so because of the way that Marvel directs the vendors. At this point, Marvel uses so much VFX in their films that all Marvel films could be considered animated films.

Disney and its subsidiaries, which includes Marvel, probably account for about half of the VFX work that’s being commissioned right now, Sam says. So if VFX studios want to stay in business, they need to keep Marvel happy.

It’s called show business, not show art

It’s hard to pinpoint when exactly things got really bad for the VFX industry. Some sources said it was inevitable. A frog in a pot. Others recalled specific projects that became flashpoints for the industry. The third Pirates of the Caribbean film, in 2007. Game of Thrones, starting in 2011. And then Life of Pi in 2013.

For Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End, Sam recalled that Disney made increasingly huge demands on the VFX studios, who managed to pull off the project despite the massive time crunch. “A lot of us in the industry saw that as a really bad thing because we recognized that we were never going to get more than this amount of money or this amount of resources because they [finished Pirates of the Caribbean]. And then that’s exactly what happened.”

“The production companies are pushing unrealistic deadlines to get the visual effects,” H said. “Game of Thrones was one of the hardest shows to work on, because you’re turning around hour-long, film-quality visual effects, times ten, in the same amount of time that you would be given to do a single movie… I’ve worked on maybe two shows where they actually had a realistic budget and timeline. Usually, you know going in that you’re probably not working with what you need.”

Conrad remembers working on the last season of Game of Thrones, which had six episodes, releasing weekly on Sunday. “We were working overtime on Friday night to finish [each episode] because they just hadn’t made up their mind on what they wanted.”

VFX studios are not suffering from lack of work, but because there is too much being asked of them for no additional compensation. Imagine you ask for pizza, and then just before it’s delivered you ask for an entirely different pizza, plus garlic knots, and it needs to get to your house 20 minutes faster. If it was even possible, you’d be charged more. But when you’re a VFX studio and Disney’s asking for more toppings, you shut up and deliver, for no extra charge. “There’s no such thing as a good client,” Ren, a VFX artist, said. “There really isn’t.”

Sam said that studios who insulate artists from these demands are few and far between. “Some VFX studios just act like a pass-through. Their attitude is that whatever the client asks for is [the artists’] problem to deal with.” If the VFX studio doesn’t moderate the production studio, then the problems that result from poor planning are only exacerbated. “There’s some responsibility on the visual effects company. But also, you know, the client shouldn’t be asking for just batshit crazy stuff.”

David said that the support positions at studios tend to be full-time staffed employees. “And for those people, they would see some pressure… but they would never really feel it because they would never have to work the 12-, 16-hour days we’d have to do to get the stuff done. They’d be happy to tell us, Hey, you have to stay [to finish these shots]. But they were never the ones staying. So, 100%, the artists on that front line are being burnt out. Way more than a lot of other positions I’ve seen in the industry.”

Burnout isn’t just coming from the fact that artists are being asked to work on the same thing over and over, or coming from the 12-hour days during crunch time, it’s also coming from the fact that VFX studios are chasing incentives all over the globe, and forcing artists to move in order to keep working.

VFX studios are forcing artist migration

Remember those tax subsidies that drive underbidding? They’re also helping fuel worker exploitation. Most VFX artists aren’t staffed positions at VFX studios, they’re contractors, brought on board on a per-project basis for six-to-nine month contracts. Which means that when British Columbia begins offering that 30% tax incentive, VFX studios begin setting up shop in Vancouver. And if you’re a VFX artist who wants to work, you have to move to Vancouver.

Ren explains that because of these tax subsidies, “all of a sudden, Los Angeles is too expensive… So [the VFX studios] fire all their employees. They make [the artists] move to Vancouver. The artists remote control the same physical computer they had in Los Angeles, but upend their entire lives. And now they’re Canadian residents.” As VFX studios chase these subsidies, artists are forced to follow the money. If there’s no contract, they lose their visa, and have to upend their whole lives, again. Many are forced to continue taking contracts at subsidy-chasing studios, regardless of conditions, work, or family.

Hector admits to having moved across borders four times in the decade he’s been working as an artist. A source told a story of a friend who has their family in Los Angeles and rents apartments in different cities for the duration of their contract. To be a VFX artist in Hollywood is to become a digital nomad, chasing studios across North America because the studios are able to exploit tax loopholes in order to convince big production companies like Marvel that they can do it better, cheaper, faster… at the expense of the very artists that they rely on to create their product.

What’s it like in a VFX studio?

Jason admits that the problems in VFX studios feels incestuous. “It’s a lot of the same filth. The same problems are circulating in the same pool of companies.” You just work with the same people over and over, in different studios, on different projects, and the issues keep coming up because regardless of the toll that these films have on the mental and physical health of the artists; the studios keep making money, and the movies keep coming out.

“Somebody got sick while working on a show,” recalled Sam (he didn’t specify for what production company), “and they felt so bad that they weren’t finishing their shots that they came in to keep working.” This is the weekend, mid-afternoon on a Sunday. Someone comes into Sam’s office and asks if he knows CPR. “The artist collapsed at their desk… They were breathing, but we had to call an ambulance.”

“Almost every studio has some sort of cry room where people will just go into and cry for 10 minutes and then they come back out and do their job.” H explained, “I have had artists who have had H.R. step in and say, ‘We have to take you off this show because it’s unhealthy and we’re concerned for your safety.’ There’s been fist fights in the middle of the studio. People just reach a cracking point… I’ve been on shows that were doing 60, 70-hour weeks for five weeks straight, full of people who don’t see their family anymore. And that’s standard across the industry.”

David recalled a moment where he was in the studio working late with another artist. “He just hit that breaking point. I could tell because we’re in the late lab doing renders at two in the morning and he’s just sitting there like, ‘Is this really worth it, man?’ He left that night and never came back. No fanfare, no fuck you’s, no letters to the supervisor. He just left.”

How long does it take to get the work done? “A basic three-second shot, of Robert Downey Jr. with all the holograms floating around? Probably 50 hours.” David explained.” What about a shot in a movie like Endgame, which can feature dozens of characters? He laughs, and can’t even come up with a number.. “Hundreds and hundreds of hours,” he estimates, “dozens of studios, hundreds of people.” All of them likely working overtime, with moving goalposts, being nitpicked by executives and directors, and many pressured to work in locations that only benefit the studio’s bid.

The fault here lies somewhere between both the production houses and the VFX studios. “I think the bar is pretty low for how studios treat these VFX artists that work under them,” said Hector. “I know a lot of people want to absolve major production houses by saying, well, you know, they’re not putting these artists under duress. They’re not working for these production houses, they’re working for these VFX vendors.” But doing so is reductive and ignores the immense pressure that the production houses put on these VFX studios. The problem isn’t with just one part of the industry, it’s with the entire movie-making machine.

Hollywood is a union town… sort of

Movies have been around for over a century. “But we’ve only been messing around with film and computers for thirty years or so,” Ren said. “So VFX came late to the party and we’re artists and we’re scared. We think if we do one thing wrong, no-one will ever work with us again.”

“Unionizing is completely stacked against us,” Sam said. The VFX studios go through so many artists so fast that by the time you get enough people to sign cards and hold a vote, there might not be popular support, or even the kind of internal volunteer structure needed to form the union.

While many sources expressed a desire to move the industry to organize into a union-based structure, artists are split on how to go about it. A lot of people want individual shops to unionize, which would put a lot of power into the hands of the artists themselves. Others think that a larger, comprehensive trade guild would be a better way to deal with overbearing clients, which would then pave the way for better working conditions in individual studios.

But the risk is high. If a shop is unionized (meaning that artists can demand more money, better working conditions, and limit the amount of control clients have to demand changes) it means that big production companies like Marvel will be less likely to accept a bid from that VFX studio. And if an artist from a union shop tries to get work somewhere else, there’s nothing in place that would stop VFX studios from looking at their union history and deciding not to hire them, because, again, most artists are digital nomads that cycle through multiple studios a year chasing work. The threat of being blacklisted, for any reason, hangs over the entire industry.

VFX is a team effort. It’s a specialized trade that requires working with extremely expensive technology and software in order to produce results. You can’t sell yourself as a one-person studio; you can only sell yourself to a studio. So the thought of doing something wrong and getting denied entry into any of those studios is incredibly intimidating. The threat of not being able to make a living creates a massive power imbalance.

Speaking to that threat is the fact that none of my sources were willing to use their real names in this article, and every one asked Gizmodo to anonymize which projects they worked on. Additionally, two sources who had originally agreed to be a part of this investigation backed out, citing that studios had cracked down on artists talking to the press since initially agreeing to be interviewed for this article.

The VFX industry is Going to Break

“It just becomes a blame game,” said H. Artists blame coordinators who blame producers, who blame executives, who blame artists. “It all just goes back to the top. Because we don’t have enough time or money to actually do the work in a way where you don’t have people who are missing their children’s birthdays. We’ve had teams sleep at the office because driving home takes too long.” H said that it’s not as easy as finding a studio with better working conditions, because eventually all artists will work on a project that has these overwhelming demands. The responsibility, H said, ultimately rests on the production houses. “Especially a company as big as Marvel, you know? Why can’t you give people a realistic schedule and budget instead of just forcing this race to the bottom? I know we’re living in late-stage capitalistic hell, but they’re creating such a toxic environment for people.”

“It’s kind of the nature of the industry that burnout is inevitable.” Conrad said. Sam said that the studios know and don’t care. “There’s just constantly a new crop of kids coming out of school who want to work in film.” But maybe burnout isn’t a strong enough word to describe what happens to some artists. Ren lists out what he’s seen happen in service to the studio: “Mental illness, physical illness, suicide.”

It’s more than just a few hours of overtime. It’s constant pressure, constant stress, and constant demands to do your work better, faster, cheaper. And while some studios can insulate their artists from this pressure, most of them don’t bother. To those studios, pleasing the client is worth burning out a few artists.

“A lot of people, they really think we just hit the ‘make cool’ button,” David explained. “They don’t really realize the sheer amount of work and hundreds of artists it takes to make anything happen.” For every single movie, every single shot, artists across dozens of VFX studios are creating bespoke, custom graphics and animations. It’s hands-on work, and it requires trade training, intimate knowledge of specific software, and, without a doubt, artistry.

The production studios benefit from everyone thinking that there’s a magic button that artists press and suddenly Tom Holland is in a Spider-Suit. They want you to imagine that the kaleidoscopic cityscapes in Doctor Strange come from a code that’s plugged into a computer that does all the work. It’s not a conspiracy, it’s not a cover up, it’s just that these companies are capitalizing on the consistent devaluation of their product and passing off the work onto the artists who make that product possible. “The business is messy,” Ren said. “It’s custom. It’s like manufacturing something that’s never been made before every time.”

So is Marvel doing something wrong? The answer is, unfortunately, yes and no. They are simply operating the way they always have; by driving down the bottom line wherever possible and facilitating a working relationship with vendors that allows them to take advantage of the institutional insecurity of the artists under the VFX studio’s employ.

Marvel may be running the movie magic machine as it’s meant to run, but that shouldn’t absolve them from the punishing working conditions that their pressure imposes on many studios. The machine needs to be remade with a priority on the wellbeing and development of the artists that actually do the custom, technical, foundational work that makes people laugh, scream, and cry in theaters, rather than espousing a ‘client-first’ mentality that allows for rampant worker exploitation. The blockbuster industry is undeniably built on the backs of VFX artists, and if it keeps going the way it is now, it’s going to break. And it’ll take movies as we know them down with it.

Update 8/12/2022: This article has been updated with more commentary from sources close to Rhythm and Hues work on Life of Pi.

Want more io9 news? Check out when to expect the latest Marvel and Star Wars releases, what’s next for the DC Universe on film and TV, and everything you need to know about House of the Dragon and Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power.