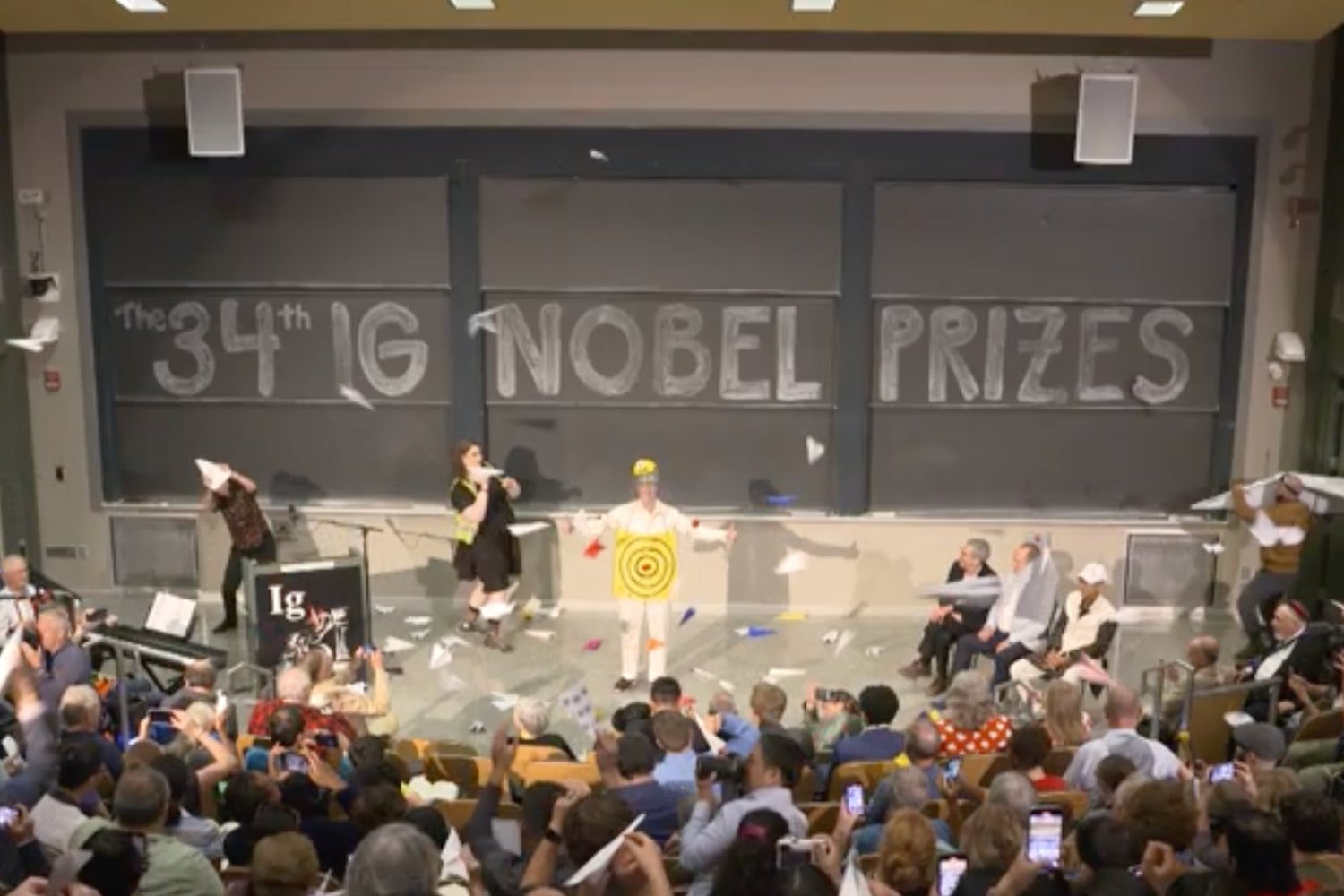

The Nobel Prizes are the “Oscars of Science,” making waves not only in the scientific community, but the lay community as well. Everyone knows there are unofficial rules to adhere to if you want to win an Oscar. Are there similar rules for the Nobels? We asked a Nobel predictor and one of the “pickers” for a prize, the winners of which tend to win Nobels, to give us the skinny on the nonscientific factors that go into picking the winner of a science prize.

The Predictions

It’s been interesting experience, trying to get scientists to comment on the politics of the Nobel Prizes. Most simply didn’t answer. Some seemed alarmed at the question. One turned down the offer because they were so upset about the winners of this year’s prizes and just wanted to detach from the process. A few sent back responses that were extremely short and can best be classified as diplomatic to the point of uselessness.

People are happy to predict the prizes. Reuters puts out a list every year, based mainly on the number of citations a scientist’s work is given in other scientific papers. Scientists are quick to publicly air humorous ideas about what makes a Nobel Laureate. In 2012, Dr. Franz Messerli made headlines everywhere when he published a correlation between a country’s chocolate consumption and likelihood of growing Nobel Laureates. More chocolate more prizes. But ask about the actual wheeling and dealing in terms of the Nobels and people get nervous.

I learned one thing—if you want to get the dish on the Nobel Prizes, go to Paul Bracher. Bracher is a professor at St. Louis University, the brains behind the blog Chembark, and has been publicly predicting the odds of who will win each year’s Nobels for a decade. He was happy to talk to me, but not nearly as happy as I was to have someone talking to me.

The Inside Scoop

Imagine my disappointment when the deep dark secrets of the Nobels are not so scandalous. What scandals there are exist more because of the structure of the prizes than anything else. These days chemists, Bracher’s colleagues, feel that they’re getting the short end of the stick. He mentions that there is a feeling in some areas of the chemistry community that “biologists are stealing the prize.” Lately the Nobels have been favoring areas like molecular biology or structural biology. Are the Nobels favoring biologists over chemists? Not really, says Bracher. The problem is, there is no biology prize. Biology, as a science, was limited back when the Nobels were first announced. Since then there has been an explosion of research, and some of that research has led scientists to look at smaller and smaller aspects of a biological entity. The line between biology and chemistry has blurred, but this has led to two nominally different sciences muscling for one highly-publicized prize.

I ask Bracher if he thinks there is anything of a cyclical element to the prizes. If a specific area, like neuroscience, receives the prize for medicine one year, is it cardiology’s “turn” the next year? “I don’t think so,” he says. Sometimes they “mix it up,” and sometimes it goes to the same discipline “three or four years in a row.”

Okay, I ask. Let’s say I make it my one goal in life to get a Nobel Prize. What should I do? Are there “hot” areas of science, which tend to get attention from the committee more than other areas? How about areas in which great scientists languish unknown because their course of study isn’t trendy?

Bracher’s advice is to find a “new instrument or a new technique,” and work with it like crazy. But, he cautions, this is just the natural flow of science. Every new technology allows scientists to break new ground and explore areas no one was aware even existed. Eventually, though, this new ground gets “picked over” and anyone wanting to make a splash has to find a new frontier. When the Nobel Prizes were first established, Bracher says, the secrets of the atom were still being unlocked and nuclear chemistry was all the rage. That’s not the case anymore and anyone working purely for a Nobel needs to go where the new discoveries are.

Then they have to wait. One trend that Bracher acknowledges is that Pretty Young Things don’t tend to get the prize anymore. It generally goes to older scientists. I thought this might be because a Nobel Prize is never given posthumously. (For good reason. Leaving aside the issue of the prize money, the Nobel Prizes would hardly be relevant if the prize for physics went to Newton every year.) Given a choice between a 38-year-old and an 83-year-old, the Committee would naturally feel pressure to acknowledge an older person’s achievement before it’s too late. Bracher disagrees—“I don’t think it works like that.” He believes that winners are getting older because the Nobels are not just a prize, they’re posterity. “The Committee wants to see if [a discovery] is robust,” he says, “before they select a winner.”

The “Snubs”

To show that age doesn’t really affect who gets the prize, he mentions this year’s big upset. John Goodenough is a physicist responsible for the lithium battery. This is what’s in your cell phone, as well as everyone else’s. It has profoundly changed the world in terms of who can communicate with whom, and how immediately they can do it. Goodenough is 93 years old, and he was considered by many the front runner for this year’s prize. The fact that he wasn’t the winner is what caused the disillusion of some of my potential sources. Though, naturally, there are many great candidates for every prize, and there’s no way to say who absolutely “deserves” to win, it’s a major shock, in terms of predictions.

No one knows what goes on behind closed doors, but I ask Bracher, in the community at large, whether there is a sense that some people have been “snubbed.”

Here we go.

Scientists gossip as much as any other profession, and they’re passionate about their work. So there are always rumors. The classic snub is Dmitri Mendeleev, a scientist who every school child knows through studying the Periodic Table of Elements, but who is a stranger to the Nobels. That omission is understandable, says Bracher. He died before the Nobels had been going on for even a decade, and they didn’t have the sense of themselves as a hall of fame.

More perplexing to many in the scientific community is Carl Djerassi, known during his lifetime as “The Father of The Pill.” The development of a birth control pill potentially changed the life of half the people on the planet. Djerassi lived to 91, dying in 2015. This was plenty of time to see the entire world change because of his work, but not enough time to win a Nobel Prize. Why? Some believe that early birth control pill tests, not necessarily the ones done by Djerassi, violated modern ethical standards—though not the commonly held ethical standards of the time—and that the Committee didn’t want to get bogged down in ethical issues. Really, no one knows.

Some omissions are explained due to the structure of the prizes. Each prize can only be divided into three parts. In 1981, the prize for chemistry was divided into two parts, shared by Roald Hoffman and Kenichi Fuikui. The prize was given, Bracher says, to each scientist in recognitions of their work in, “chemistry conservation in orbital symmetry.” More than two scientists made important contributions to this, so many people wondered why three people weren’t honored. Bracher speculates that the prize was only shared between two people because Robert Burns Woodward, a scientist who had worked with Hoffman, had died in 1979, and the lack of a third scientist was a kind of silent tribute to him.

This three person rule, while sensible in terms of dividing the prize money, seems to cause a lot of uproar. Science is no longer one person tinkering in their private lab. Many people make a contribution to each discovery. So the problem, Bracher believes, is that each year the Nobel Committee has to make the choice between, “not recognizing a discovery or recognizing it and cutting someone.”

Paul Bracher has two major sore spots, in terms of people left of out of Nobel pantheon. One is Gabor Somorjai, who worked with and was almost universally honored alongside Gerhard Ertl in the area of surface chemistry. In 2007, Ertl won the prize and Somorjai did not, a fact that caused much confusion in the chemistry community.

The other is Gilbert N Lewis, a chemist who worked in the first half of the twentieth century. He came up with an acid-base definition that chemistry students all learn. In 1946, after being nominated multiple times every year but never winning the prize, he met for lunch with a rival who had won the Nobel Prize, and later died in his lab under circumstances that led people to believe he died by suicide. Lewis has attained a kind of martyr status among some in the chemistry community, because they believe that his grudge against chemist Walther Nernst, and Nernst’s friends’ grudge against him, are what kept him from the prize. Was that the case? No one knows, and Lewis isn’t the only one to inspire stories about petty personal grudges keeping someone from being recognized. Bracher says, “There are always rumors.” He doesn’t know whether they’re true. What he’d like is a little more transparency in the process.

The Prize-Giver

We can’t have that with the Nobels, but I was lucky enough to talk to someone who gives out a different top scientific prize. The Perl-UNC Neuroscience Prize was established in 2000, by Dr. Edward Perl and Dr. William Snider of the University of North Carolina. Five of the prize-winners have gone on to win Nobel Prizes. I spoke briefly with Dr. Snider about the prize-giving process and what he thinks of the Nobels.

Snider doesn’t entirely agree with Bracher, when it comes to the factors that go into awarding a Nobel Prize. “The only thing I would say,” he tells me, “is I would be surprised if there were some personal issue that caused a deserving person not to get it.” As for whether age factors into the decision, he is more inclined than Bracher to believe that older people get consideration, saying, “That wouldn’t surprise me.”

He believes that it is possible, though, that a scientist might be able to “market” themselves in such a way that they are more likely to get any prize, including a Nobel. What does this marketing entail? Snider thinks that “garnering attention in the lay press,” will get a lot of scientists on the map. Popular attention can translate into attention in the scientific community.

He’s right there with Bracher, though, when it comes to the way to earn a Nobel. Find a new technique and a new instrument and work it. That’s why, he believes, there has been an overlap between the Perl-UNC Neuroscience Prize and the Nobels. Neuroscience is taking off. He has particular high hopes for a technique called optogenetics, and a technique worked out at UNC, DREADDS, which can “take any group of neurons that have a molecular signature and suppress and activate the group.” This will enable neuroscientists to study the brain in more detail, and without cutting it up or shocking it with electricity.

But what about people with their eyes purely on the prize? What goes on behind closed doors? He’s a little more hesitant about this part of the process. (No scientist wants to know that they almost received a prestigious prize so we don’t get into details about who gets cut and who gets awarded the prize.) The most important step is getting tons of nominations from as many scientists as they can find willing to nominate people. They email, phone, and contact as many people as they can. They want a wide range of candidates before they ever start talking.

What about when they do start talking? Do things get heated, I ask. “Things get complicated. Most discoveries are not made in isolation. There are two to three people in each category.” And, like the Nobels, the prize becomes useless if you split it too much. UNC doesn’t have pockets as deep as the Nobels, so the cash prize, meant to help the winner’s research, is $20,000. No one would say no to that, but split it too often and it doesn’t do much good. It’s at this stage that the upsets occur. Snider admits that sometimes a dark horse comes through. He has begun a conference sure that one person would win, only to realize, after some talk, that a person he hadn’t considered is a better candidate. This might explain what happens during the Nobel talks. Perhaps that committee also began talking about the person everyone in the world assumed would win, only to talk their way to someone else.

And maybe the Nobel Committee feels the same way Dr. Snider does: “We don’t make the best selection every year. How do you define the best selection?” He’s just confident that they find a really good scientist every year.

Make Your Own Damn Prize!

Bracher, when I talk to him, agrees with this. “We have to remember that this isn’t a government agency. It’s just a guy who made a lot of money. If you don’t like it—you make a lot of money and die and set up your own society.”

I ask him what he would do. “I’d set up something a little more amendable. Have money set aside for new prizes. Maybe don’t award every prize every year, maybe every other year.” He’d also make voting public, or at least give people the option to go public. And he’d make the committee bigger and more diverse. He says, “You need a large sample size to combat shenanigans,” which is too good a line to ignore. He’d include science reporters, previous laureates, and national representatives on the committee. “Do it more like sports,” he says.

Let’s have Deadspin weigh in on that.