During his State of the Union address in February, President Donald Trump reiterated a promise he had made a year earlier: By 2030, the United States would bring an end to the HIV/AIDS epidemic that first took root nearly 40 years ago. It’s the sort of sweeping assurance that seems too good to be true, given Trump’s track record of broken pledges and his administration’s attempts to slash HIV-related programs and public health priorities.

Yet, many public health experts believe it’s more than possible to effectively eradicate the disease by 2030, both in the U.S. and across the world. It’ll take lots of work, though, and we’re not getting off to the right start.

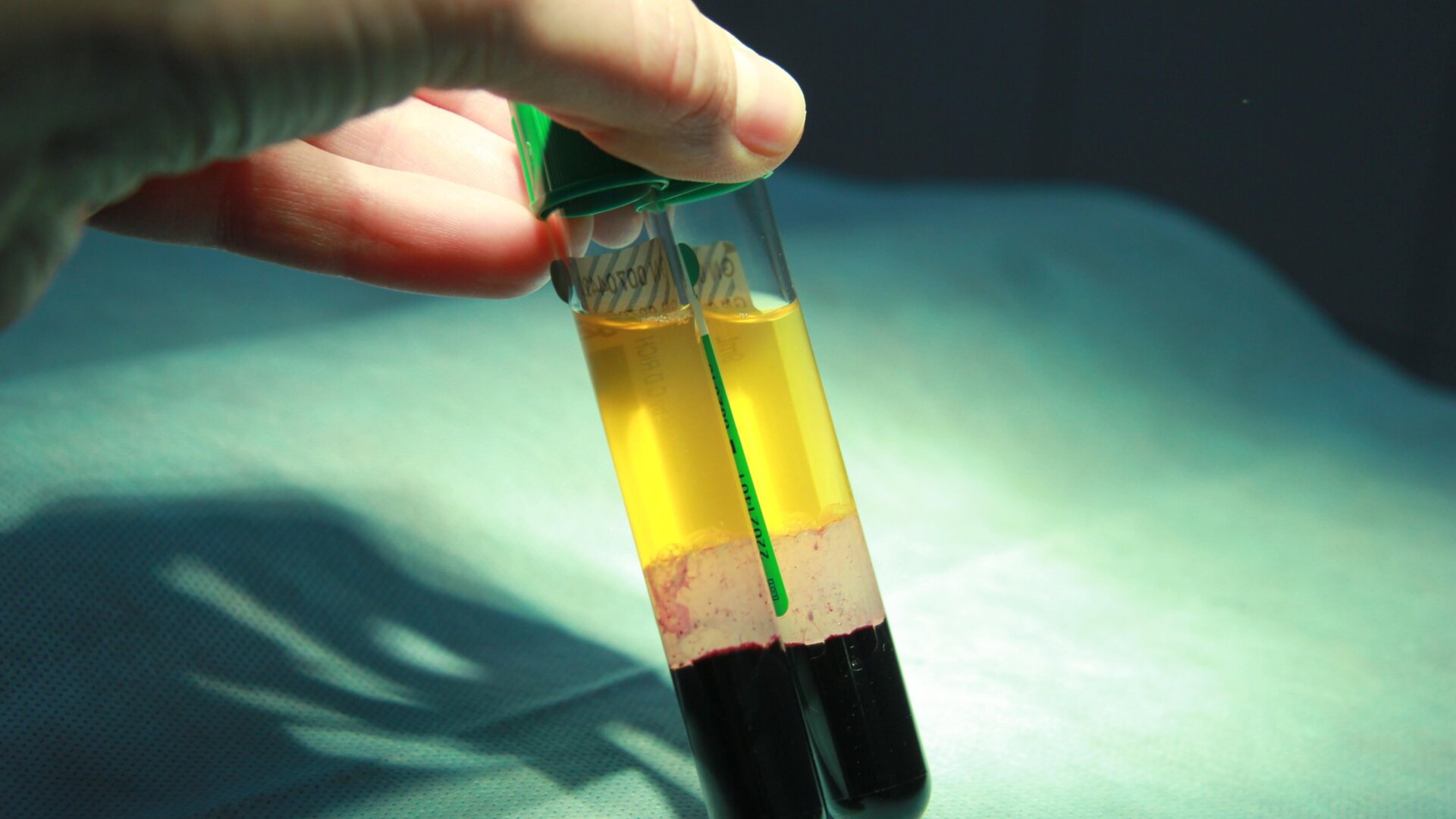

HIV infection remains a lifelong diagnosis for the 25 million people estimated to have it worldwide. But for decades, we’ve had antiretroviral medications that can dramatically reduce the level of virus in someone’s body and prevent the last, often fatal stage of infection that wipes out the immune system—acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). As a result, the average person who starts HIV treatment early now has a near-typical life expectancy, and many have viral loads so low they’re unable to pass on the virus to anyone else.

In more recent years, scientists have also been able to retrofit some of these drugs into a cocktail that can be used as a safeguard against the blood-borne and sexually transmitted virus, known as pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP. People on PrEP aren’t completely invulnerable to HIV, nor is the treatment necessarily affordable, but if taken daily as recommended, the regimen reduces the risk of contracting it through sex by 99 percent. Alongside PrEP, there are still condoms—male and female—that can prevent the spread of HIV as well as other STDs that make it easier for a person to catch HIV.

And there are also syringe exchange programs that provide sterile needles to people who use intravenous drugs to reduce their risk of infection. These exchange programs not only lessen the chance of HIV transmission in a community but also help connect people who use drugs to the health care system, where they can be screened for HIV and receive antiretroviral therapy if needed.

These new and old interventions have enabled the creation of a brute-force strategy to short-circuit what’s been a pandemic disease since the 1990s. The idea is to find hidden HIV cases through screening, especially in high-risk groups; help get patients treatment that can hopefully make them non-contagious; and help vulnerable populations lower their risk of catching it.

In 2016, the United Nations published a report outlining its goal for ending HIV as a public health threat worldwide by 2030. To do so, the authors estimated, we would need fewer than 200,000 new infections per year, while 95 percent of people would know their HIV status, 95 percent of HIV-positive people would be on treatment, and 95 percent of those on treatment would have the virus fully suppressed.

Some places, like New York City, are shooting for an even faster demise. In 2014, the state government announced its Ending the Epidemic initiative, setting a timetable of 2020 for HIV eradication. According to Keosha Bond, a public health researcher at New York Medical College who studies HIV prevention, the plan seems to be working.

“I’ve been able to see over time the change in trajectory of what has been going on within our city and how their new efforts have made such a great impact on the incidence rate of HIV within our community,” Bond, also a former employee at the New York City Department of Health, told Gizmodo by phone.

The city’s success has come from making PrEP more easily accessible and affordable through added Medicaid funding, giving registered nurses the ability to screen people for STDs, and funding clinics that can provide low- or no-cost testing and treatment services. These efforts have largely targeted populations at higher risk of HIV, such as men who have sex with men and the communities of color that researchers like Bond work with.

As of 2018, according to metrics released by the program, the initiative seems on track to meet its targets by 2020: 65,000 NYC residents taking PrEP; fewer than 750 new infections a year; and the viral suppression of at least 85 percent of patients taking antiretroviral therapy.

Bond thinks that New York’s success can certainly happen throughout the country, while even more could be done to help marginalized populations.

“I feel like these are strategies that other communities around our country can replicate, with their approach of looking at the whole HIV care continuum, and not just focusing on one aspect of HIV prevention,” she said. “The issue with PrEP has been that uptake has been low among some populations, like black and Latino men and women and transgender individuals. So how can we reach the individuals who are most affected by HIV? We know it works, but there’s still some challenges that we are facing in getting people connected to these services.”

Despite New York City’s success, there are reasons to be worried about the near future of HIV prevention in general. Trump’s 2030 initiative, which has earmarked some $291 million in funding, has only recently started to get underway. Meanwhile, the Trump administration has undermined itself elsewhere, with proposed cuts to programs meant to help the global eradication effort and to programs that make housing more affordable for people living with HIV. It has succeeded in cutting Title X funding to clinics that provide family planning services, including contraception, because they provide abortions or refer pregnant people to somewhere else where they can get an abortion. And the administration has cleared the way for states to cut funding for Medicaid, the most common source of coverage for HIV patients.

“Trump is interested in ending HIV/AIDS. And yet he presented a proposed budget that dramatically cuts a lot of different sources of science funding that would go to HIV research,” Rowena Johnston, vice president and director of research at the nonprofit organization amfAR, The Foundation for AIDS Research, told Gizmodo via phone. “So it’s a little bit of a confusing and mixed message, when he clearly has this goal.”

The U.S. healthcare system in general is also worse at taking care of people living with HIV. Compared to countries like the UK and Canada—similarly wealthy countries that, unlike the U.S., provide universal healthcare coverage—rates of viral suppression among treated HIV patients are lower in the U.S.

One major reason for this lower suppression rate is that HIV treatment costs people far more in America. The CDC estimates that the lifetime health care costs of a person with HIV are somewhere around $485,500. Much of this financial burden is placed upon insurance providers and assistance programs, but these higher upfront costs lead to higher out-of-pocket costs in the U.S., which will inevitably force some people to ration or stop taking the drugs entirely. A study this past December found that 7 percent of HIV patients have had trouble adhering to their prescriptions because of cost, while 14 percent have needed to find ways to save on their drugs.

And the drugs needed to keep people with HIV healthy aren’t getting any cheaper either. A research paper this February found that the costs for initial antiretroviral therapy between 2012 and 2018 in the U.S. have steadily increased past the point of inflation, meaning that companies are raising the price to make more profits, not because they have to.

A similar stumbling block for prevention has been the high price tag of PrEP. The list price of Gilead’s Truvada—until recently the only available form of PrEP—is about $2,000 a month. Even if people have insurance, taking PrEP will still often force them to pay high co-pays and deductibles that make them unable to afford it for long. These high market prices also impact publicly funded programs like Medicaid, leading to their own form of rationing. Wealthier cities like NYC are more able to shoulder these costs and other aspects of HIV prevention and treatment, like screening, but other parts of the country, particularly rural areas, aren’t.

Some reforms are on the way. In 2021, insurers will be forced to cover PrEP without any cost-sharing for high-risk patients, thanks to a recommendation made last year by a government-appointed advisory board that PrEP should be a widely provided preventive service. And Gilead will be forced to release a generic version of Truvada later this year, following a failed court battle with the U.S. government over its patent rights. A single-payer “Medicare for All” system, where the government provides essential insurance coverage for everyone and is able to strongly negotiate down drug prices, would almost certainly broaden access to and lower the costs of PrEP and antiretroviral therapy.

Worldwide, the eradication effort is also running into some stumbles. Since the early 2000s, we’ve drastically reduced the number of new infections and HIV-related deaths, particularly in Africa where the majority of people with HIV live. Over time, though, these annual gains are getting less and less impressive. A UN report in 2019 found that we’re likely to fall short of the UN’s global targets for 2020 across the board and that we’re not on track to eliminate it by 2030. In 2018, according to the World Health Organization, 1.1 million people newly contracted HIV.

The lack of funding has set back these efforts. The UN has requested a $26 billion annual commitment by 2020 from its members for its program. But in 2018, the UN only received $19 billion, which was $1 billion less than it had gotten the year before. Aside from the lives that additional funding would help, this short-sighted thriftiness is likely costing the world financially: According to research cited by the UN, every dollar of money that goes into ending the HIV epidemic faster would bring $2 to $6 in economic returns down the road.

There are other concerns when it comes to the virus itself. In many countries, we’re starting to see people with treatment-resistant strains of HIV. A WHO report in 2018 found 12 countries across Africa, Asia, and the Americas where at least 10 percent of HIV positive patients had strains resistant to two common front-line drugs, a threshold that makes it dangerous to keep prescribing them to the rest of the country. There are still other HIV drugs doctors can use instead for these cases, but it’s something that could seriously hamper treatment down the road.

Ideally, the best way to solve HIV permanently would be to find a cure or vaccine. But the elusive nature of the virus, which hides itself in reservoirs of the body during treatment and can quickly reemerge when someone stops medication, has long stymied scientists. Promising areas of research, such as the “shock-and-kill” strategy to wake up dormant HIV particles so they can be taken down, haven’t gone anywhere near as well as we’ve hoped. And this past month, a clinical trial of a vaccine candidate in Africa was ended early in “deep disappointment,” after an independent panel found no evidence that it was working.

“One thing that staggers me with every new piece of information we learn about HIV is how many weapons it has in its stash, so that at every turn, HIV is able to protect itself against everything that we throw at it,” Johnston said.

Johnston is hopeful about the future of other developing strategies, such as gene-editing technologies like CRISPR that could go after the virus itself or indirectly strengthen the immune cells HIV tries to infect. Researchers are also on the cusp of creating longer-lasting antiretroviral regimens that should allow people to go weeks or months between doses, with at least one Phase III clinical trial underway as of last year. These treatments should make it easier for people to stay HIV-suppressed, while also reducing the risk of resistance.

An HIV cure or vaccine would surely be a monumental achievement, but they may not be available in time to play a major role in the next decade. Fortunately, we don’t necessarily need either to bring the HIV epidemic to its knees. But we will need to adapt in how we reach out to the people most likely to be affected by it, Bond said.

“I recently gave a lecture to class about sexual health equity, and about how the one-size-fits-all model for people does not work,” she said. “We know now that how you address the health of a single mother living in a rural area who has to take care of children is not the same way you’re going to be addressing it for a 16-year-old white man living in the city.”

The biggest challenges to HIV eradication remain human-made. Crucial public health interventions such as syringe exchange programs in the U.S. are still underutilized and demonized by some, including the current vice president. The fear of stigma and misconceptions about HIV still make people reluctant to get tested. Poverty and pharmaceutical greed still keep people away from literally life-saving medications.

Getting rid of HIV forever will not be easy. But a better world is possible, one where the scourges of the present can be vanished by the unity of many.