It was a mansion that any drugs baron would happily call home. There was its ostentatious decoration: gold and cream furniture, sparkly wallpaper and an aristocratic bed. It boasted a formidable armoury: swords, an axe, knives, a baseball bat, nunchucks, a baton and an illegal stun gun. Plus it held clandestine financial reserves: nearly £35,000 of cash in sterling, euros and Emirati dirhams, some of it rolled up inside Louis Vuitton, Chanel and Gucci handbags, the rest hidden in sofas and drawers.

What really left officers taken aback when they stormed this Staffordshire property in 2019, however, was not its contents but the level of protection designed to stop intruders. One member of the UK’s National Crime Agency, who has investigated violent gangs for 29 years, tells i: “That’s the most fortified house I’ve come across.”

“To get through the gates initially was problematic,” he explains. “Then you get to the house and it’s bulletproof glass, bulletproof patio doors. These individuals do that to stall our entry [during a raid], so they can secret wealth and whatever evidence they think they can hide from us.”

He believes this security was probably designed with an additional goal: “To stop other like-minded criminals, bearing in mind the level of violence this group operated in.”

The owner of the building was Thomas Kavanagh, head of the British arm of the Irish-led Kinahan cartel. This is one of the most powerful and most dangerous organised crime syndicates in the world. It smuggles vast amounts of cocaine into Europe, has been linked to at least 20 murders – including two innocent bystanders – and is “a threat to the entire licit economy through its role in international money laundering”, according to US officials. They are even alleged to have links to Russia and Iran.

“These are really good-quality villains,” says the NCA investigator. “I would put them among a handful who control everything at that level.”

For years, the name of this gang meant nothing to most people in the UK, though it’s long been capable of provoking fear in Ireland. One woman in Dublin was given a suspended prison sentence this summer for threatening workers at a pharmacy by falsely telling them her last name was Kinahan – the judge said it would have been frightening for staff when “that particular surname was invoked“.

The group’s leader is Dublin-born Daniel Kinahan, who lives in the United Arab Emirates. He is apparently known as “The Cap” by his associates (for the simple reason that he likes wearing caps), and “Cancer” by his enemies (because his gang is so deadly). The tale of his group and its rivals is full of nicknames worthy of a Guy Ritchie film: Kavanagh is known as “Bomber”, while the rest of this real-life cast includes Dapper Don, Rocketman, Flash Gary, Frizzy, The Monk, Duck Egg, Fat Freddie, The Penguin, Johnny Cash and, more prosaically, Daithi.

Sports fans began hearing more about Kinahan after he established himself as a boxing promoter in order to claim he was a legitimate businessman. This sportswashing attempt, through the guise of his management company MTK Global, led to him being photographed in 2017 with Tyson Fury. The heavyweight champion lauded Kinahan personally in 2020 for trying to set up a fight between him and Anthony Joshua.

This year, however, his criminal empire has been in the spotlight like never before – and seems to finally be unravelling.

The conviction of Kavanagh, labelled in court as Kinahan’s “right-hand man”, was a major success. He considered himself “untouchable”, according to the NCA, but pleaded guilty to “orchestrating the importation of multi-million-pound drug shipments” and was sentenced in March to 21 years in prison.

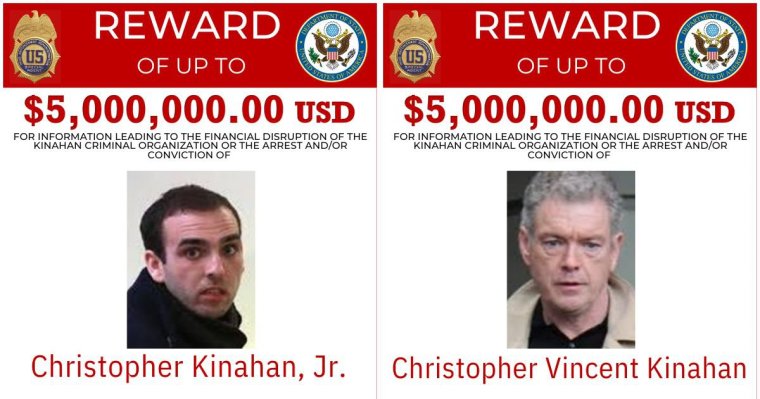

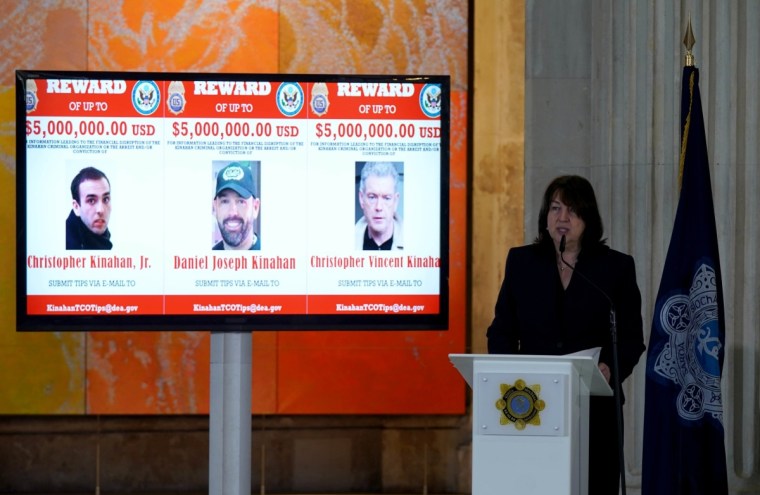

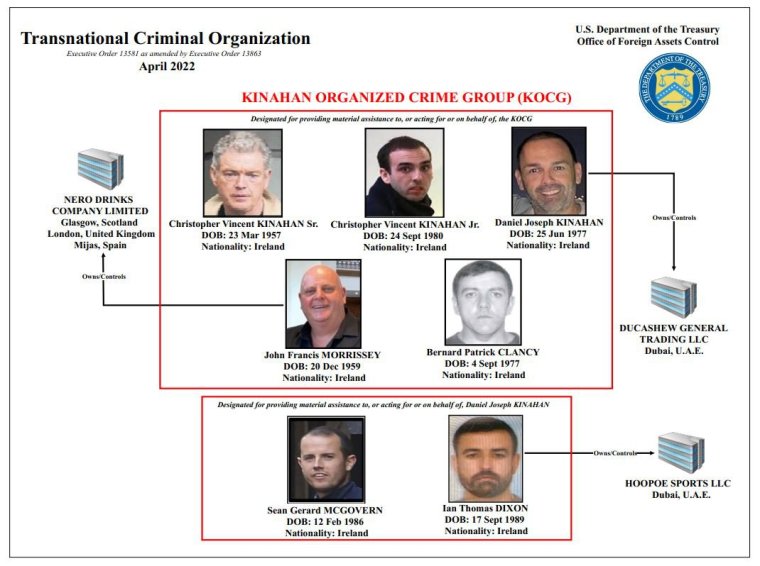

What really made the rest of the world take note of the gang, however, was a dramatic press conference in Dublin a few weeks later. Backed by Ireland, the UK and the EU, the US government announced it was imposing sanctions on the Kinahan organised crime group and seven of its members. It also offered three $5m (£4.45m) rewards for information leading to the arrest of its leader, his father Christy and his brother Christopher Jr.

The sanctions were a big deal, especially as they were introduced while Western officials were already so busy targeting the regime of Vladimir Putin.

Another NCA officer – one of two who have spoken to i on condition of anonymity and are working on the Kinahan investigation – says: “OFAC [the US Office of Foreign Assets Control] had told us that if Russia invaded Ukraine, their resources would be pulled in that direction and it might not go ahead. But it did. That’s perhaps an indication of how important it was to them – and us – to get this done.”

He underlines how the group poses direct threats to lives in the UK, saying: “We’ve disrupted up to eight potential murders or incidents of serious violence.”

More than six months on, Daniel Kinahan is thought to remain in Dubai, living as a free man. At least, as free as someone can be when their family and anyone they do business with are effectively barred from the Western banking network.

But after the arrest of another key lieutenant, the Manchester-born “enforcer” Johnny Morrissey, in Spain in September, it seems the end of his reign could be close.

This is the story of the gang’s rise – and why police are confident they will soon bring it down.

“Their rise has been meteoric”

Crime author Nicola Tallant

The gang’s dramatic rise

The Slade Valley Equestrian Centre seemed like an innocent business. Just outside the Irish capital, it offered stables for up to 30 horses while its owners traded in steeplechase racers. But in 2002 police stopped a van driven by its manager, Raymond Molloy, and found 498kg of cannabis resin, a haul worth €6m back then. Officers raided the centre and found more drugs, including cocaine, as well as guns and ammunition.

Molloy was set to face trial but disappeared while on bail. It took 11 years for him to be found. He had faked his own death by leaving his clothes beside a lake in Dublin and had begun a new life on the Isle of Wight. Molloy was finally jailed in 2017.

One of the officers involved in the case was Séamus Boland. He has since risen through the ranks to become head of the National Drugs and Organised Crime Bureau for An Garda Síochána, the Irish police force known as the Garda. Even two decades on, he remembers this “very interesting story” well. “That was linked to the Kinahan organised crime gang, without a doubt,” Detective Chief Superintendent Boland tells i. “What it highlights is their significant, established drug trafficking going back 20-plus years.”

The founder of this criminal enterprise, Daniel’s father Christy Kinahan, was already well known to gardai. His first convictions came in the 70s for burglary, car theft, forgery and handling stolen goods.

Kinahan Sr was jailed for six years in 1987 after a heroin seizure, but at that time he was merely a street dealer. It was the 2002 raid that convinced detectives the Kinahan family were involved in a far bigger operation.

For people only learning of the Kinahans today, it can feel like trying to start The Sopranos in season five. Fresh stories about the gang emerge in the Irish tabloids almost every day. Perhaps nobody can explain their origin story better than Nicola Tallant, Investigations Editor at Ireland’s Sunday World newspaper and author of Clash of the Clans: The Rise of the Kinahan Mafia and Boxing’s Dirty Secret. As a crime journalist in Ireland “you couldn’t ignore the Kinahans”, she says. “Their rise has been meteoric.”

Kinahan Sr had a middle-class upbringing and is “a very intelligent, ruthless and entrepreneurial man”, she says. “He is one of those people with amazing charisma and business prowess. He would have risen to the top of whatever industry he decided to go into.” He chose crime.

It is part of the Kinahan legend that this patriarch studied French while he was in prison and even refused an early release to complete a degree in the language. He also reportedly taught himself law and is now fluent in Spanish and Dutch too.

“Our strategy is disrupt, dismantle and prosecute”

DCS Séamus Boland

Daniel is known to be “very likeable” but is a “complex character”, says Tallant. “He is where he is because of his father. There’s a lot of jealousy around that.”

Explaining Daniel’s background, she says: “His father chose to go into crime, whereas Daniel followed his father’s footsteps. He was brought up in a very working-class flats complex by his mother [Jean Boylan], who was a cleaning lady. By all accounts, she was a very nice woman. The area would have been ravaged by drugs and she did quite a bit of community work and was very kind to addicts.

“She tried to keep both her sons away from the drug empire. But their father was just so powerful, so wealthy, and the allure of it must have been too hard to turn away from.”

From the late 90s, the family and their allies expanded into the south coast of Spain, trafficking drugs from Africa across the Mediterranean into Europe. “We were watching the export of a lot of their childhood friends and dealers to Spain. We could see how they were just growing and growing there,” says Tallant.

In 2010, the authorities launched a crackdown. Searches carried out under Operation Shovel, underpinned by Europol, led to more than 30 arrests in five countries including the UK. Christy, Daniel and Christopher Jr were all detained on the Costa del Sol. “They were supposed to have been taken down,” says Tallant, “but they were back up and running within two years.” The aftermath of Shovel is said to have been when leadership of the group passed from father to son.

Daniel Kinahan’s mother died in 2014. He and his brother went back to Dublin for her funeral, which was reportedly monitored by armed police, though Christy did not attend.

They were now becoming more influential abroad. “They were making the connections which turned them into what the DEA called a European ‘super cartel’. They joined together with the Italian mafia, the eastern Europeans and the Dutch Moroccans and became this powerhouse of cocaine suppliers,” says Tallant.

The prosecution of Kavanagh revealed the kind of smuggling techniques they use: a six-tonne industrial tarmac removal machine seized at Dover, for example, was found to contain 220kg of cannabis and 15kg of cocaine.

“Within the criminal underworld here in Ireland, for years they were all-powerful, and anybody linked to them was all-powerful,” says Tallant. “Anybody in their cell structures was feared, revered, and you never turned on them.”

In September 2015, the head of a rival gang, Gary Hutch, was shot dead in a gated estate near Malaga. It sparked a feud between the two groups that has resulted in 17 further killings.

Irish police worked ever more closely with colleagues abroad as they attempted to fight back, and they had their successes. Together with a colleague who cannot be identified, Boland has been awarded the Merit Order Cross of the Guardia Civil by the Spanish police, partly for his work in securing the conviction of James Quinn – a Kinahan enforcer with more than 70 convictions – over the murder of Hutch.

But the defining event in the Kinahan-Hutch bloodbath came in 2016: the retaliatory assassination attempt on Daniel Kinahan at Dublin’s Regency Hotel. The venue was hosting a boxing weigh-in when masked men, disguised as Irish police, swept into the building with assault rifles and opened fire. Their target escaped. Kinahan’s associate, David Byrne, did not.

A non-jury trial by the Special Criminal Court finally began last week, with Gary Hutch’s 58-year-old uncle, Gerry “The Monk” Hutch, accused of murdering Byrne. He denies the charge and proceedings – in what has been called Ireland’s “gangland trial of the century” – are expected to last three months. Two other men, Jonathan Dowdall and his father Patrick, pleaded guilty to facilitating the killing.

“The Regency attack is what really engaged the Irish public with the Kinahans – the fear about Kalashnikov weapons being produced at a hotel reception,” says Tallant. “A lot of it was recorded on smartphones. It brought into people’s minds the idea of gangland crime becoming a threat to the state. It was terrorism. There was a general election that month, and this event was so big that some politicians called for the election to be put off, so the government could handle this problem of organised crime. It had been going on for years but everyone had been ignoring it.”

Though the incident could have ended his life, Daniel Kinahan appears to enjoy the notoriety it brought him. In the online trailer for an interview he gave to a Scottish YouTuber, James English, we get a snippet of his account.

“I see him there, maybe six metres from me,” says Kinahan, sitting in a white T-shirt and beige trousers, with a pair of glasses hanging from his neck. “Then I see the gun at the back and then I go” – at this point he makes a noise to indicate him running away – “and then I hear boom-boom, boom-boom, shots let go behind me…”

The full interview, which was apparently three hours long, has never been released. English said it would have allowed people “to hear Daniel tell his side of the story” – but apologising to his followers a few days after the trailer was released, he explained he had been “told not to show” the video in legal advice.

It was probably a wise move. Less than a month later, Kinahan was publicly named as one of the most-wanted men on the planet.

“Intimidation is their game”

National Crime Agency officer

How police are closing in

When US Ambassador to Ireland, Claire Cronin, stood up to reveal the sanctions and three $5m rewards in Dublin City Hall on 12 April, this legal broadside took even experienced crime journalists by surprise. The gang, officers believe, will not have seen it coming.

Garda Commissioner Drew Harris said the gang will eventually run out of money and friends, telling them directly: “You can run but can’t hide from justice forever.”

Behind the scenes, transatlantic co-ordination between the US, Ireland, Spain and the UK had been going on for four years, says Boland. He travelled to Washington DC for meetings with high-level officials in the East Wing of the White House.

“Organised crime groups at the higher level really operate like global business enterprises. They’re almost like a multinational corporation,” he says. “The US Treasury Department doesn’t issue sanctions controls against people because friends in Europe ask them, ‘Would you do this for us?’ It’s a very, very strict process.”

One of the NCA officers says the sanctions have “definitely had a big impact upon that group. They can’t trade in the US dollar, they can’t trade with US businesses. The US dollar is the global currency for the boxing industry and any business, so it will have massively frustrated them.

“It has knock-on effects, too. It’s not just about the group itself, it’s anybody who is associated with them – I’m dealing with investigations that relate to somebody who knows somebody who knows somebody… As well as tying their hands, they become more toxic and people don’t want to be associated with them.”

A hotline was also established for informants to come forward, perhaps tempted by those $5m rewards. Has anyone taken the risk of calling the number? “We have received intelligence that is of interest to the UK,” confirms one of the investigators. “I’m sure our foreign partners have received intelligence that’s beneficial as well.”

There were big ramifications for the boxing world. Asked about the sanctions a few days after they were announced, Tyson Fury said he had “absolutely zero” links to Kinahan, but paid the price for their past dealings when he was apparently barred from entering the US in June.

Daniel Kinahan has always protested his innocence. In the trailer for his interview with James English, he says: “The media, it manipulates everyone… These papers wrote that I supplied these guns to these rebel kids in Africa, I had a billion dollars’ worth of cocaine that went through America – come on. If this really happened in America, I’d be in America now.”

The Dublin press conference, however, showed just how certain authorities feel about the group’s level of criminality. They have kept up the pressure, with Daniel Kinahan’s Dublin home seized by police this month.

One of the men named in the sanctions package is already in police custody. Johnny Morrissey, who ran the Nero vodka firm with his wife Nicola, was arrested in bed at gunpoint in September. He is accused of laundering €200m in just 18 months.

Extraordinary footage of the raid on his villa, released by the Spanish police, shows Morrissey sitting bare-chested in handcuffs while paintings are taken off the wall and computers are analysed. A sniffer dog wags its tail as piles of cash are counted and a machete is unsheathed. The tropical shorts he is wearing only add to the indignity for a man used to being photographed at glamorous promotional events for his Glasgow-based drinks brand.

“They’re still free to go about their business – and their business is crime”

National Crime Agency officer

But the three main players – Daniel, Christy and Christopher Jr – are all still at large. “We’ve disrupted these people, but the job isn’t done,” says one of the NCA officers. “They’re still in the UAE, we believe at the moment. Although it’s much more difficult for them now, they’re still free to go about their business – and their business is crime.”

Other Kinahan associates also remain free. Liam Byrne, whose brother was killed at the Regency Hotel, attended the Champions League Final in Paris in June. This was despite him being named in Irish courts as the leader of his own organised crime group, and even having his house in Dublin seized by police.

It may seem puzzling how officials from several nations can publicly state that specific people are involved in serious organised crime, yet they have not been apprehended.

A few days after the sanctions were revealed, the UAE announced it was freezing the gang’s assets and was investigating its activities.

However, the cartel has carried on trying to secure its position in the the country through relationships with “rogue princes”, Tallant believes. “I know Daniel Kinahan has been very friendly with a member of the royal family in the Emirates – one of those princes who have the title and probably have the money but don’t actually have access to the power.”

She has been unimpressed with the UAE’s actions so far, but realises progress may be under way behind the scenes. “Maybe they really do want to clean up Dubai, because it is the new ‘Costa del Crime’. There are criminals from all over the world there.”

The lack of an extradition treaty with the UAE is one hurdle. “We have to deal with legal frameworks, those discussions are always quite sensitive,” acknowledges Boland. But he believes a breakthrough is possible. “The UAE has extradited serious criminals back to a number of European jurisdictions.”

There are other reasons why the Kinahans have not yet been arrested, investigators explain.

First is the “massive difference between intelligence and evidence”, says one of the NCA team. Information may become available, but it needs to be legally admissible and strong enough to win over a jury. “We know lots of things about lots of people. But the challenge – the hard part – is turning what we know into [a case with] a good evidential standard, which 12 people good and true will be convinced of beyond all reasonable doubt. It’s evidence that puts people away.”

While sources may privately inform on the Kinahans, persuading them to risk testifying in court is another matter. “If you look at what violence these people have been involved in, very rarely do you get witnesses coming forward,” says one of the officers. “Intimidation is their game.”

Criminals at this level are also adept at foiling investigations, he explains. “It’s not uncommon for us to work on people who have coached themselves or attended training on counter-surveillance. That’s not only aimed at us, that’s aimed at the other baddies that want to rip them off. They need to have their wits about them, because other criminals may well want their wealth or their drugs.”

“The Kinahans are screwed – the house of cards is about to collapse for them”

Crime author Nicola Tallant

It takes bravery to fight gangsters like this. For the officers involved in the case, “the risks are very real”, says one of the NCA team, particularly during arrests, searches and spying operations. “When we’re observing these individuals, they may not necessarily think that the person they saw three times is a surveillance officer, they may think they are from another crime group and seek to assault them.

“Officers feel the nerves. Sometimes it’s excitement because they’re getting key pieces of evidence. But they put themselves in dangerous situations to protect the public.”

His colleague adds: “It can mean a lot of time away from your family, as well. It takes a toll.”

The authorities are also prepared to be pragmatic. They do not necessarily need to prosecute Kinahan members with huge, headline-grabbing charges. “Sometimes you look at the old analogy with Al Capone,” says one of the NCA officers, pointing to how the famed 30s mobster was convicted for tax evasion rather than more dramatic crimes.

While the police understand the urgency of stopping the group, they are willing to be patient in achieving their ultimate aims. “Our strategy is disrupt, dismantle and prosecute,” says Boland. If they are not in a position to arrest and charge someone, they instead do everything they can to impede their criminal operations.

The NCA officers agree. “We are in it for the long run. From acorns become oak trees… We may start with an investigative strategy of looking at somebody further down the tree, just building up our evidence. Eventually we take that tree down.”

Even when criminals are sent to prison, the police do not rest there. Months after Kavanagh was jailed, they are still “relentlessly” investigating his finances, suspecting he still has fortunes squirreled away.

Tallant admires this root-and-branch approach to take apart a whole criminal operation, rather than just going for the biggest names. “Look at what the US has been doing for years in their war on drugs. Look at when El Chapo was finally arrested: he was brought across the border, put on trial in Brooklyn and eventually he goes away for the rest of his life. But what they left behind in Mexico was the Sinaloa Cartel. Now it’s being run by his sons – and nothing has changed.

“For the Kinahan organisation and others linked to them, this is almost a new blueprint in policing. I don’t think it has ever been done in this way before.”

She is confident these efforts will bear fruit – and soon.

“The Kinahans are screwed – the house of cards is about to collapse for them. They’re toxic. Nobody’s going to do business with them.

“It’s only a matter of time. There are bounties on their heads, they’re wanted and there are information lines open. Everybody is running for the hills, they’re trying to shore up what money they can. They still have a lot of money, which will give them a lot of power. But who do they trust? Where do they go?

“There are certain countries that might welcome them with open arms, telling them to come in and bring their money with them – and then they’ll just hand them over and keep all the cash. That’s the way it goes.”

Twitter: @robhastings