River campaigners in Wales have hit out at the practice of spreading waste from sewage treatment works on farmland, warning that a lack of oversight means it risks further damaging polluted rivers.

They warned that many of Wales’s watercourses were already saturated with nutrients and that the human waste was likely to be contaminated with “forever chemicals”, microplastics and pharmaceuticals.

The practice of giving so-called biosolids to farmers is widespread in the water industry as a way of disposing of the vast amounts of sludge it produces each year.

In the case of Welsh Water, the waste is offered free of charge to farmers who meet the company’s criteria and are within 40 miles of its major treatment works in Wrexham, Cardiff and Port Talbot anaerobic digesters, which run on sewage.

For centuries, human waste was known euphemistically as “night soil”. It would be collected in urban areas after dark and was often sold on to the agricultural trade as fertiliser.

The modern practice is much more sophisticated, with a not-for-profit body set up by the water industry accrediting the biosolids and setting out requirements for farmers to prove that they need the fertiliser.

Campaigners told i that in theory using biosolids was a good idea which reduced the need for artificial fertiliser and its associated carbon emissions, but that they feared not enough was being done to make sure it was used in an ecologically sound manner.

“The process itself is not unreasonable, it’s just how well it’s managed,” said Kim Waters of the Welsh Rivers Union. “Welsh Water just want to get rid of the stuff because they’ve got to put it somewhere.

“There is no way Welsh Water know where it is spread. It’s not as if it’s delivered to the site and the farmer spreads it on the spot.”

Charles Watson, chairman of River Action, told i that industry self-accreditation was not enough and that “any initiative like this should be subject to regulatory supervision.

“If the soil or crop can naturally absorb the nutrients then this is a good circular economy solution. However if the net effect is that the application overloads already nutrient-saturated soils then this is simply transferring sewage pollution from rivers onto the land, where it will simply end up back in the river.”

While farmers are required to follow rules on how to use fertiliser and manure near watercourses, the agricultural industry is still responsible for around two thirds of pollution problems in UK rivers.

When excess nutrients wash off the soil into rivers this feeds algal growth which can smother waterways and deplete them of oxygen, asphyxiating fish and other wildlife. There are also occasional incidents of large amounts of manure washing directly into rivers and poisoning them.

Only 44.5 per cent of Welsh rivers achieve good ecological status, according to government figures, with 60 per cent of rivers in Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) suffering excess nutrient levels.

Gail Davies-Walsh, chief executive of the Welsh Rivers Trust, told i that the level of nutrients in Welsh soils was still too high, even when it was tested for suitability. “The soil doesn’t really need that nutrient, it certainly doesn’t need it on failing SAC rivers. It’s just another problem to add to the list,” she said.

Welsh Water told i: “We take our responsibility to both protect and enhance the environment seriously and are committed to ensuring the responsible use of biosolids in a manner that is safe and sustainable. We have measures in place to ensure that they are applied in a way that reflects best practice, and does not harm the environment or public health.

“We operate under the UKAS Accredited Biosolids Assurance scheme, which sets environmentally conservative limits to protect the soil and water courses. This helps to ensure that the biosolids are not applied in areas where the soil already has high nutrient levels or near SAC rivers.”

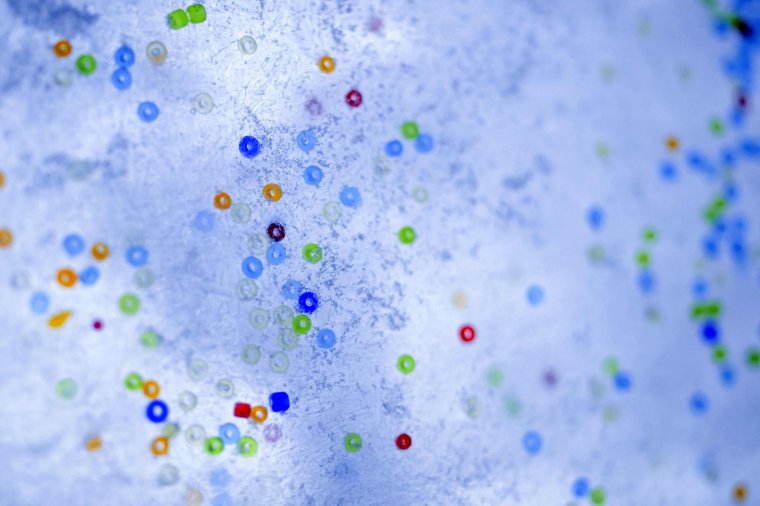

Beyond nutrients, campaigners also worry that human waste will contain microplastics, pharmaceuticals and PFAS, also known as forever chemicals. All three are harmful to wildlife and are not currently treated for in sewage works.

“The most important angle to all of this is what’s contained in that sludge is a truckload of other stuff, of which there is virtually little regulation or no regulation, and very little testing,” said Mr Waters.

“You’re just spreading microplastics and all the other bits and pieces on farmland which, in Wales in particular, when it rains it’s just a matter of time before it ends up in the river.”

Welsh Water told i that the issue of forever chemicals, microplastics and pharmaceutical pollution was a matter for the regulator and government.

“These are ‘control at the source’ issues which the Welsh, UK, and EU governments are assessing, as they represent a societal challenge. We expect further controls to be exerted at all three levels. We have been lobbying for a ban on wet wipes which contain plastics for many years, and we hope that there will also be a ban on the production, use, and sale of the most harmful of the PFAS group of chemicals to enable water quality improvements,” the company told i.

Natural Resources Wales said it enforced the existing laws under the Sludge use in Agricultural Regulations (1989), these are meant to ensure that there is no build up of toxins from sewage in agricultural land.