During his four years in office, former US president Donald Trump cut off almost all international financing for global climate efforts. On April 22, the Biden administration reversed this policy, announcing the US will double its climate contributions to $5.6 billion annually by 2024. The pool of money includes streams from federal agencies like the US Development Finance Corporation and contributions to the UN-managed Green Climate Fund that aim to help poor countries adopt clean energy and adapt to climate change impacts.

The number left many analysts underwhelmed. Biden’s plan inches the US closer to taking responsibility for its historic emissions, but has yet to meet the mark. During the 2015 Paris climate summit, countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) agreed to raise at least $100 billion annually by 2020. Only about $80 billion has been raised so far, and much of that comes with expensive strings attached. An Oct. 2020 Oxfam report concluded that developing countries ultimately pocketed only $25 billion out of $60 billion delivered to them as climate finance between 2017-18, after deducting loan repayments and interest.

Climate finance is stingy and inequitable

The basic premise of climate equity is that rich countries, especially the US, are responsible for the vast majority of historic greenhouse gas emissions. Poorer countries, therefore, are owed damages from climate change, plus the costs of transitioning to a low-carbon economy, states Georgetown University philosophy professor Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò explained during a Quartz-hosted conversation on the social media app Clubhouse about climate “reparations” (full audio of that conversation is below).

And there’s more to climate equity than just money, he said. Access to technology and intellectual property needed for climate adaptation is unevenly distributed. Voting power in the UN, World Bank, and other multilateral institutions is concentrated in the hands of rich countries. “All those things have to be renegotiated if we are actually going to share this planet with each other rather than live under terms of domination,” he said.

But money is a good start, said Charlotte Streck, director of the international climate policy consulting firm Climate Focus which advises developing countries on climate policy and finance. But what these governments want most, she argues, are direct, unrestricted cash transfers and grants. “That’s something that developed countries are not so keen on,” she said. “They would like to link climate finance to particular investments. Developing countries would like to see it with none or minimal strings attached, but developed countries would put a lot of bells it. The hoops that [developing] countries have to jump through are endless.”

According to the Oxfam report, 80% of climate finance is delivered as a loan (for a solar energy project, for example), rather than a grant. And often, the money is contingent on achieving specific environmental outcomes, from rainforest conservation to industrial decarbonization. But that arrangement is backward, argues Streck, and impedes the pace of climate action. To implement conservation measures, poor countries need cash up-front, she said.

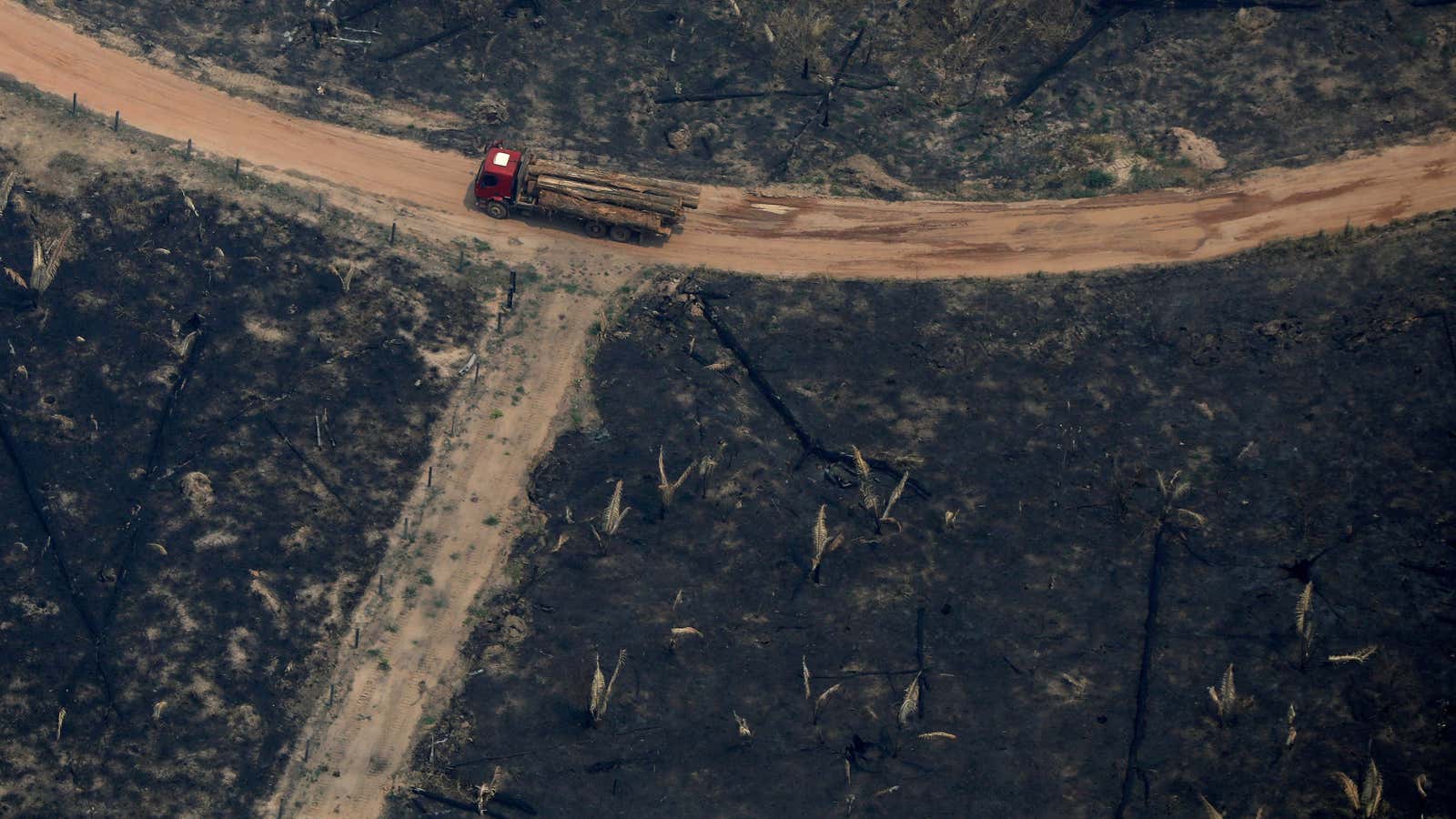

“In the last ten years, this model has led to very little deforestation reductions,” she said “In fact, we have an increase in the loss of natural forests. We need to rethink this assumption that [developing country] governments would just put policies in place with the prospect to get, five or ten years later, some finance on results.”

Meanwhile, the $100 billion target is really only a down payment. The true costs of climate adaptation in developing countries could rise to $500 billion annually by 2050, according to the UN. The only way to raise that much, argues Rémy Rioux, CEO of the France’s Development Agency, a public development finance institution, is by making loans to profitable investments. “It makes no sense to imagine that we will finance the transformation of our economies by grants only,” he said in an interview on April 22. “There’s no need for that, if we want to make it sustainable. It would be a waste of resources. Many sectors we have to transform have a business model, and are able to repay loans.”

The limits of private-sector climate finance

What about climate finance from the private sector like a new plan led by Amazon, Nestlé, and other companies to spend a cumulative $1 billion this year on carbon offsets based on tropical forest conservation in Brazil and elsewhere? The private sector’s growing thirst for carbon offsets and ability to put pressure on high-emissions suppliers could open a deep well of capital for developing-world conservation, adaptation, and clean energy efforts.

But that approach, Táíwò said, only puts even more public natural resources under private control—the same inequity that caused climate change to begin with. The upshot, he said, is that the US and other governments need to kick in much more than they are, but be willing to cede some control of how the money is spent.

“I think this has to be done with public funding,” he said. “The climate crisis is what has happened given centuries of situations where shareholders and corporate executives have been able to socialize the costs of their economic operations while privatizing the benefits. So if we’re talking about private companies investing in anything—call it green, orange, purple or any other color—we’re talking about a fundamental intervention that is designed to do the same thing that caused the climate crisis.”

You can listen to the conversation in full here: