What happens when we run out of food?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOur modern society relies upon complex, modern supply chains for food. How would we cope if they were to suddenly collapse?

Worst Case Scenario

This article is part of a new BBC Future column called Worst Case Scenario, which looks at the extremes of the human experience and the remarkable resilience people display in the face of adversity.

It aims to look at ways people have coped when the worst happens and what lessons we can learn from their experiences.

It happened almost overnight. Rešad Trbonja was an ordinary teenager growing up in a thriving, modern city, one which only a few years earlier had hosted the Winter Olympics. Then on 5 April 1992, the place he had called home was suddenly cut off from the outside world.

What he – along with almost 400,000 other inhabitants trapped inside Sarajevo by the Bosnian Serb Army – could not guess was that it was the start of a nightmare that would last nearly four years. In the Siege of Sarajevo, ordinary residents trapped inside the city would go about their lives to a daily thump of artillery and crack of sniper rifles. Even simply crossing the street or queuing for bread would become a life-threatening experience as the soldiers on the hills surrounding the city took pot-shots at the local populace.

But while the bullets and shells fired into their city were a constant threat, Trbonja and his neighbours faced another, quieter foe from within: hunger.

“The food began to run out almost immediately,” recalls Trbonja, who was 19 years old at the time and now teaches school children about the war in Bosnia. “The little bit of food in the stores went pretty quickly and many of the shops were looted. A cupboard and a fridge at home doesn’t hold very much when you're feeding a whole family, so it didn’t take long for everything to be gone.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBy the time the siege ended in January 1996, more than 11,500 people in Sarajevo were dead. Many died in the hail of shrapnel, explosives and bullets flung upon them, but almost certainly some perished of cold (gas and electricity were cut off) and starvation.

But Trbonja remembers that despite the death and near constant destruction, the people of Sarajevo found extraordinary resilience.

“People in suburban areas with gardens would grow vegetables they would share,” says Trbonja. “They would give seeds to their neighbours so they could grow some vegetables in flower boxes on their balconies. The taste of those tomatoes grown on your own balcony was beautiful.”

While the international community dithered about how to intervene in the escalating war in Bosnia, Canadian troops – acting as part of a United Nations peacekeeping force – managed to reopen Sarajevo’s airport. It was a crucial step. Through the siege, more than 12,000 UN humanitarian aid flights brought in 160,000 tonnes of food, medicine and other goods.

“Without the humanitarian aid, Sarajevo would no longer exist,” says Trbonja. “Ninety per cent of the population lived off food distributed by the UN. Those who were extremely rich could exchange jewellery, paintings, anything of value, for extra food on the black market.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFor those without anything to exchange, they needed other ways of supplementing their meagre food rations. Trbonja, who like many young men in Sarajevo picked up a gun in a desperate attempt to defend their family and home, would give blood at the city’s hospital when he returned home from fighting. In return, he’d receive a can of beef.

“We had to find other ways too,” he says. “We would search through books to find out what plants were edible so we could make salads out of flowers. There were days where we only had a slice of bread and tea to see you through the day and others when there was nothing. It was real survival mode.”

Talking to Trbonja, it is hard to believe this unfolded in the heart of Europe less than 30 years ago. But stories like his have not been consigned to history either.

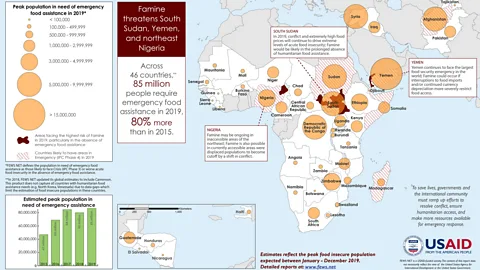

Thanks to conflict, political unrest and drought, the world is currently in the midst of its worst famine since World War Two. According to the Famine Early Warning System, a US organisation that predicts humanitarian emergencies, 85 million people will require emergency food assistance in 2019 across 46 countries – equivalent to the populations of the UK, Greece and Portugal put together. An estimated 124 million people face food crisis, according to the UN’s World Food Programme.

The number of people at risk of famine has increased by 80% since 2015 with South Sudan, Yemen, north-west Nigeria and Afghanistan among the worst hit.

But while images of hunger-bloated children from the Ethiopian food crisis during the 1980s have become seared onto Western consciousness, these modern famines are occurring almost unnoticed.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPart of the reason is that the world seems to have convinced itself that famine doesn’t occur any more. It’s true that the toll of famine has lessened. According to Alex de Waal, executive director of the World Peace Foundation at Tufts University in Boston, Massachusetts, one million people died every year from famine in the 100 years leading up to 1980s.

“Since then the death rate fell to 5-10% of that,” says de Waal. “We no longer had entire societies starving. The growth of global markets, better infrastructure and humanitarian systems nearly abolished famine. Until the last couple of years, that is.”

Famine is now re-emerging as a threat. The cause? War – and bad politics.

“It is really hard work to starve people as they are tremendously resilient,” says de Waal. “You need a truly bad government that actively pursues the kind of policies that deprive people of what they need and degrade the environment. That is what underlies the famines we are seeing in places like Syria, South Sudan and Yemen.”

It is one of the ironies of our modern world. Thanks to global food chains and international trade, we can transport produce across oceans in just a few days. We can find our supermarket shelves stacked with produce from all over the world, even from countries next door to those experiencing famine.

FEWS NET

FEWS NETBut even in developed nations, the prospect of food shortages are perhaps not as far away as we might like to believe. The international food chains that supply us with our favourite foods are precariously balanced.

And it doesn’t take a catastrophe like war or drought to disrupt them. In Venezuela, a country blessed with rich oil reserves, a political crisis driven by rocketing inflation has led to shortages of food and medicine, forcing families to live off rotten meat and leading millions to leave the country all together. The Eurozone crisis that sent Greece’s economy to the brink of collapse also brought food shortages to the struggling country.

Meanwhile, disease, poor weather and rising prices have led to shortages of a number of popular crops in recent years. Soaring rice prices led to panic buying in the Philippines and other Asian countries in 2008, causing a supply crisis for this staple food. Bad weather in Europe in 2017 saw prices of many vegetables rise while there also were worldwide shortages of avocados after several countries were hit by poor harvests.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe fuel protests that hit the UK in 2000, where farmers and hauliers blockaded oil refineries and fuel depots, led to supermarkets rationing food as they struggled to get deliveries to restock their shelves. Even the stockpiling of food by schools, care homes, hospitals and pessimistic shoppers in the UK ahead of Brexit show what effect even the mere rumour of food shortages can have.

It is important to clarify that food shortages do not lead to famine and most famines are not caused by a shortage of food – rather, the access to food. It is only once starvation creeps into being a mass experience that it becomes a famine.

But food insecurity is more common than many of us might think. The UN’s Food and Agricultural Organization estimates there are nearly 821 million undernourished people in the world. In the US, one of the world’s biggest food exporters, nearly 12% of households are classed as being food-insecure and some 6.5 million children go without adequate food.

Hunger pains

What does hunger do to you? Due to the ethical quagmire of running experiments on this, scientists have instead had to rely on the experiences of those who have survived periods of starvation and famine.

“In the short term, there’s weight loss as you metabolise your spare fat and muscle tissues,” says Bradley Elliott, a physiologist at the University of Westminster who studies the effect of starvation in a man who went 50 days without food. The human body is able to cope with surprising levels of weight loss: as the body loses 20% of its weight it consumes 50% less energy. Body temperature drops, while lethargy and apathy take hold as the body tries to conserve what little energy it has. Eventually, however, the organs themselves begin to waste, all apart from the brain, which seems to be an adaptation to protect it from famine.

“Liver and kidney problems also seem to occur,” says Elliot. “Blood pressure regulation is also impaired, which means people can faint easily."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAs the lack of minerals and vitamins take hold, diseases like scurvy and pellagra emerge. Children tend to be more vulnerable than adults, quickly showing the signs of wasting and succumbing to infectious diseases, according to the World Food Programme’s Rita Bhatia when she reported on the severe food shortages in North Korea in the 1990s.

Survival without food can depend on a person’s body weight, how many calorific reserves they have in their fat, and other health conditions they may be suffering from. Women tend to be more resilient than men. But in general, most people will die if their body weight falls to half of normal body mass index – which usually occurs after 45-61 days without food.

For those that survive, there can be lasting impacts.

Long term starvation can affect people’s height, leading to stunting in populations who have lived through famine and severe food shortages. Those who were aged between one and three years at the start of the Great Famine in China, which saw up to 30 million people die between 1959-1961, were on average 2.1cm shorter as adults than those who did not grow up during the famine. They also had thinner arms, were 4.4% lighter and on average achieved lower educational attainment. Miscarriages among pregnant women go up, too.

Infants who survived the Ethiopian famine in the mid-1980s were more likely to suffer illness in adulthood, while other studies have shown a long list of health issues, such as high blood pressure, diabetes and heart disease are more common in later life among children who live through periods of starvation.

But the impact of starvation goes beyond physical health. During the Great Chinese famine, labour fell by 25%, drastically affecting the country’s economic output. Children who survived the Ethiopian famine earned 3-8% less per year over their lifetime than their contemporaries.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhile these studies can provide some clues, they fail to convey the agonising, maddening pain of real hunger.

Oonagh Walsh, a professor of gender studies at Glasgow Caledonian University, has found that the number of people being committed to psychiatric asylums rocketed during and immediately after the Irish Famine between 1845-1851.

“There was a huge rise in committals to asylums from a population that was effectively halved during this time,” she says. “Some of these might be people seeking a decent meal they know they will get at an asylum, but there was also a shift in the way people thought.

“People quickly became very fatalistic. The famine was worst on the west coast where they have access to the sea and fish. It doesn’t make sense until you realise that people had sold everything they had, including their nets and boats. The starving population resorted to trying to trap birds, eating grass, weeds, and straw.”

It gives some clues about how people try to cope with sudden loss of their food supply.

Coping mechanisms

During the Dutch famine of World War Two during the winter and early spring of 1944-1945, the starving populace began foraging plants and mushrooms in an attempt to survive.

“In the Netherlands, a relatively rich, densely populated country with little natural vegetation, foraging was not a common practice anymore when World War Two started,” says Tinde van Andel, a professor of the history of botany at Leiden University in the Netherlands. People turned to old recipe books on wild plant preparation and elderly relatives to learn how to gather and cook foods that were safe to eat. They consumed sugar beets, tulip bulbs, potato peels, nettles and wild fungi.

Getty Images

Getty Images“Groups of urban people started foraging trips into the countryside,” says van Andel. “Anyone who could grab a piece of land turned it into a vegetable garden. People raised rabbits in their city patios. They also stole animal fodder from farms or agricultural waste.”

Many of London’s famous royal parks were turned into allotments and gardens during World War One and World War Two as people attempted to feed themselves. And while rocket is today a fashionable addition to any salad, its use originated from during World War Two when Italians foraged for food in the surrounding countryside.

More recently, the threat of food shortages is forcing people to consider more traditional careers. Following the economic crisis in Greece and the accompanying food shortages, applications for schools that teach farming soared in the aftermath of the crisis.

And this could stand them in good stead. According to Alex de Waal, rural populations tend to survive famine better than those in urban areas.

“In the traditional famine prone areas, people have their own farms and their own ways of surviving,” he says. “They have stores of knowledge. In Africa, grandmothers will know about foods, fruits and nuts they can get from the forest. These people tend to do a lot better.”

For Rešad Trbonja, the memory of that 47-month-long nightmare he found himself in in 1992 will never fade. But amidst the horror and misery he experienced, he believes his city survived the war and food shortages with nourishment of a different kind.

“The whole of Sarajevo became a huge family,” he recalls. “We were very kind to each other, sharing things with one another. It was something I’ve never seen before. I’m very privileged that in a time of desperation and misery, to have seen Sarajevo more beautiful than ever.”

--

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.